Amycterini

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/ 10.5281/zenodo.293976 |

|

DOI |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6206704 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/2B6F645C-AA06-FFF6-FF69-2BABFBEFC2BD |

|

treatment provided by |

Plazi |

|

scientific name |

Amycterini |

| status |

|

Tribe Amycterini Waterhouse

Amycteridae G. R. Waterhouse, 1854: 75 (footnote). Euomides Lacordaire, 1863: 309, 315. Psaliduridae Pierce, 1914: 350.

This group of large, ponderous weevils, iconic of the Australian weevil fauna, is not only the largest but also the best-studied tribe of Cyclominae , having been taxonomically treated first by Macleay (1865, 1866), then by Ferguson in 17 papers between 1909 and 1923 and lastly by Zimmerman (1993). Zimmerman’s copiously illustrated work modernised Ferguson’s treatment significantly but did not greatly alter the concepts and numbers of the genera and species ( Richardson & Oberprieler 2007), and he himself recognised it only as a preliminary guide to the group rather than as a complete revision and that his amycterine classification was in need of corroboration by genital studies.

Schoenherr (1823) first placed his genus Amycterus in a division Amblyrhinides but later ( Schoenherr 1826) included it together with Cyclomus in his division Cyclomides. Waterhouse (1854) proposed a family Amycteridae for Amycterus and four other Australian genera ( Acantholophus Boisduval , Euomus Schoenherr , Mythites Schoenherr and Tetralophus Waterhouse ), and Lacordaire (1863) divided the group into two sections, the Amycterides vrais ( Amycterus , Acantholophus , Cubicorhynchus Lacordaire and Phalidura Fischer von Waldheim) and the Euomides ( Amorphorhinus Lacordaire , Euomus , Mythites and Tetralophus ), based on the length of the scapes (passing the posterior margin of the eyes in the former but not in the latter). Zimmerman (1993) found this difference unworkable but tentatively kept Lacordaire’s groupings as subtribal entities (Amycterina and Euomina) based on the different structures of their oral cavity, although a number of genera have both conditions. A third family-group name, Acantholophini, was proposed by Schenkling & Marshall (1931b) but is nomenclaturally unavailable because it is not accompanied by any description, as required for names published after 1930 (see also Alonso-Zarazaga & Lyal 1999).

Controversy surrounds the name of the type genus of the tribe. As with Somatodes, Schoenherr (1823) did not furnish a description for either the genus Amycterus or for its type and single included species, A. talpa , but since Amycterus is the only genus included in his Cohors 2 of Subdivisio 1 of the division Amblyrhinides, which is briefly characterised, both Amycterus and talpa are in fact validated by this short combined description (as are Somatodes and sanctus in this paper, see above). Alonso-Zarazaga & Lyal (1999) consequently reinstated Amycterus as the valid name over its synonym Phalidura Fischer von Waldheim, which was also published in 1823 but, in the absence of a precise publication date, is deemed to have been issued on the 31st December 1823 (Art. 21.3 of the ICZN (1999)), whereas Schoenherr’s paper was published on the 7th October of that year.

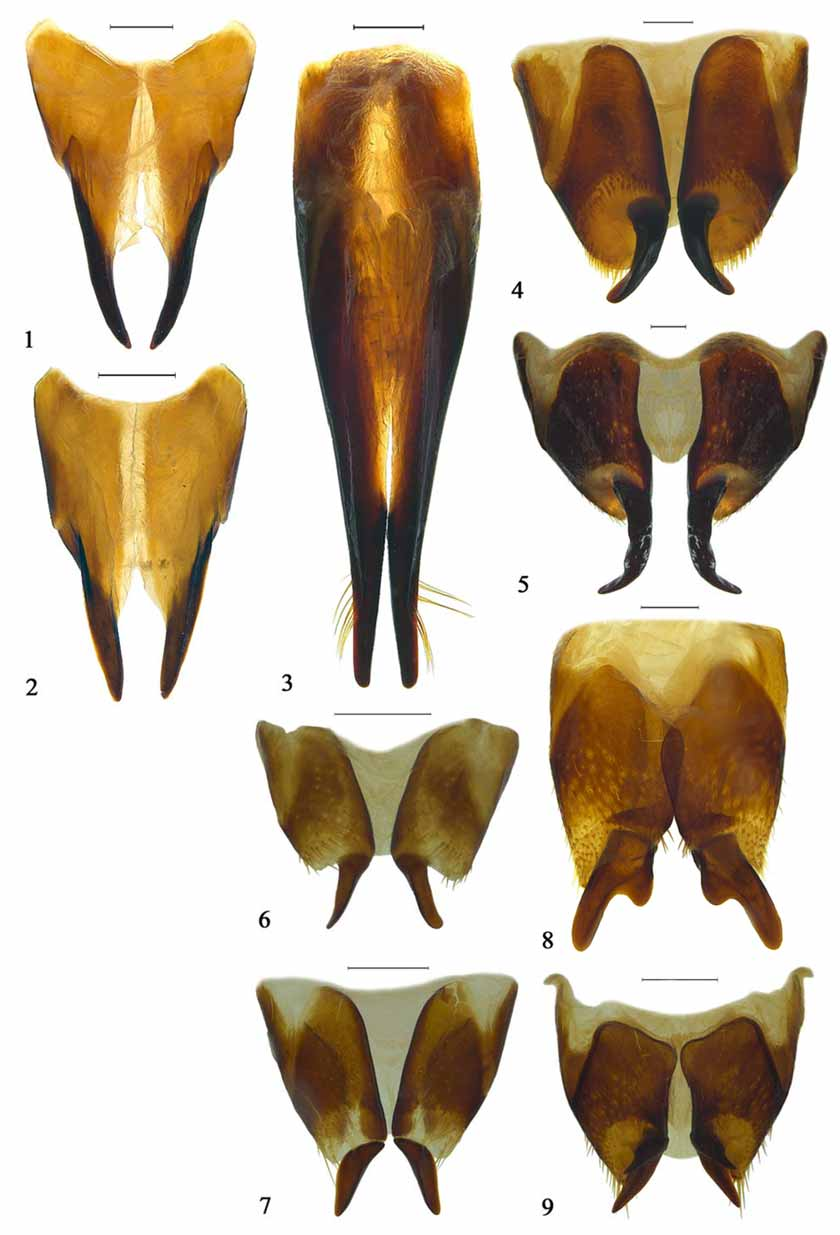

Despite his long text on the Amycterini , Zimmerman (1993) provided no details of their diagnostic characters other than a few features distinguishing the group from “Somatodini”. In the context of other cyclomine tribes, the Amycterini may be diagnosed by the following characters: rostrum shortened; epistome with posterior edge mostly raised, sharply carinate; mandibles generally plurisetose, sometimes densely setose or squamose, blade-like elongated with usually a single subapical cusp; maxillae enlarged, strongly sclerotised, coarsely sculptured, palpi on ental surface; labial palpi small, concealed; scrobes short, deep or posteriorly shallow, mostly running towards lower angle of eyes; funicles 6-segmented; eyes generally flat; prothorax generally with slight ocular lobes; metepisternal sutures completely obliterated; tibiae mucronate, without spurs; tarsi with pulvilli usually absent or sunk into pockets on tarsite lobes; ovipositor ( Figs. 4–9 View FIGURES 1 – 9 ) short, broad, strongly sclerotised, distal gonocoxites large, proximal gonocoxites smaller, laterally shortly extended anteriad, styli subterminal to dorsomedial, large, claw-like, curved outwards to downwards, sometimes bifid, without setae but generally surrounded by a field or ring of strong setae at their bases.

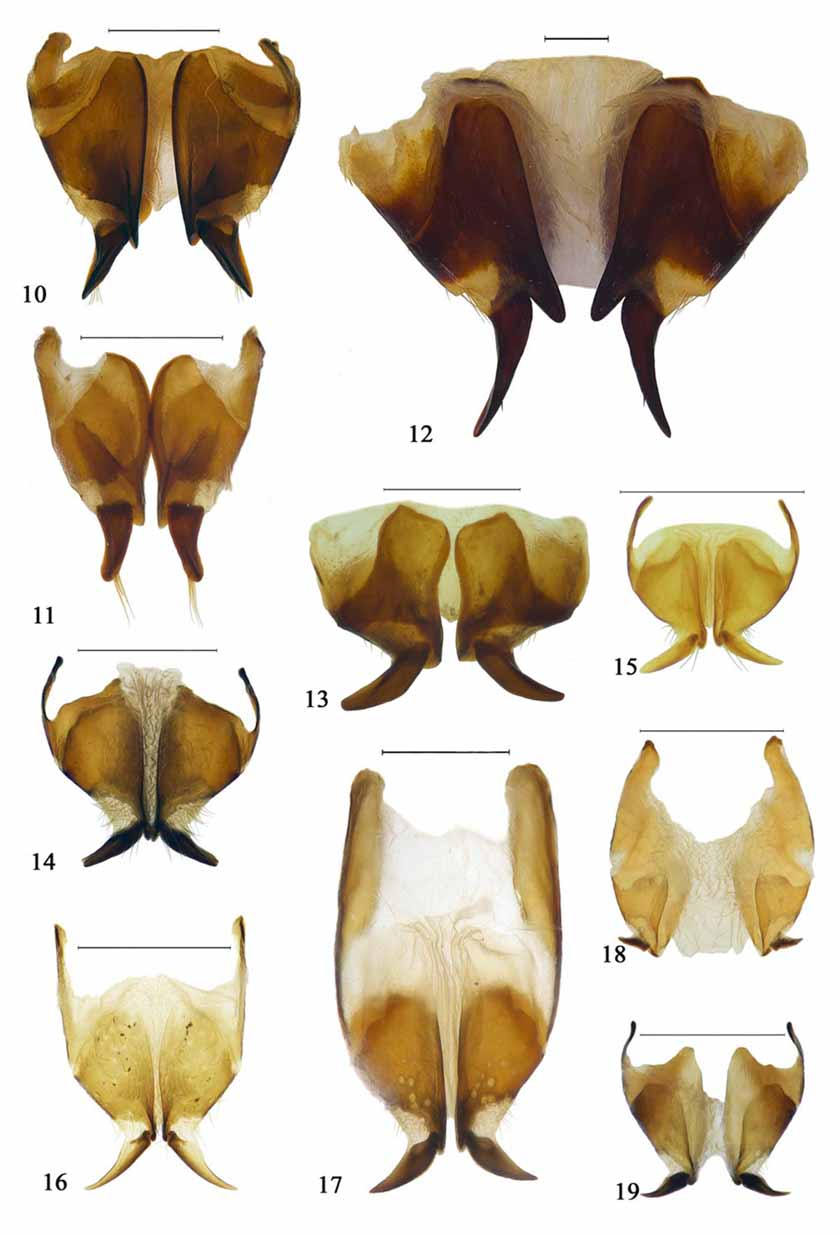

This type of ovipositor, featuring strong, claw-like styli without setae, is consistent in all Amycterini and evidently synapomorphic for the genera included in the group. A similar type occurs only in the Hipporhinini (below), most probably indicating a close relationship between these two tribes. Essentially the amycterine ovipositor differs from that of the Hipporhinini only in the position of the styli, whose insertion is not terminal in Amycterini but more apicomesal to dorsomedial and exceeded laterally by the apex of the distal gonocoxite. In Hipporhinini, by contrast, the styli are placed more properly apical to subapical and their insertion is only slightly and narrowly exceeded mesally by the apex of the gonocoxite ( Figs. 10–19 View FIGURES 10 – 19 ). As a result, the articulation membrane of the stylus is laterally exposed (“open”) in dorsal view in Hipporhinini but not so in Amycterini . This distinction appears to pertain to a difference in the plane of movement of the styli, being lateral in Hipporhinini but more to entirely dorsoventral in Amycterini .

As Zimmerman (1993) portended, the structure of the ovipositor carries taxonomic significance also within Amycterini . In its simplest (presumably plesiomorphic) type, the styli are subterminally positioned, gently curved outwards and more or less simply cylindrical to slightly compressed to become subspatulate with a sharp dorsal carina, and the proximal gonocoxites are often also laterally shortly extended anteriad as in Hipporhinini ( Figs. 6–7 View FIGURES 1 – 9 ). This type occurs mostly in the smaller forms, in the genera Acherres Pascoe , Alexirhea Pascoe , Amorphorhinus , Atychoria Pascoe , Brachyrothus Marshall , Chriotyphus Pascoe , Dialeptopus Pascoe , Ennothus Pascoe , Euomella Ferguson , Melanegis Pascoe , Oditesus Pascoe , Pseudonotonophes Ferguson and Tetralophus . In the bulk of the Amycterini , represented by the genera Achorostoma Uther Baker & Thompson , Aedriodes Pascoe , Amycterus , Antalaurinus Zimmerman , Cucullothorax Ferguson , Dicherotropis Ferguson , Euomus , Gagatophorus Jekel , Hypotomops Uther Baker & Thompson , Lataurinus Ferguson , Myotrotus Pascoe , Mythites , Notonophes Sloane , Ophthalamycterus Ferguson , Sclerorinus Macleay , Sclerorrhinella Ferguson , Sosytelus Pascoe and Talaurinus Macleay (probably also Talaurinellus Zimmerman , of which seemingly only males are known), the styli are longer, stronger and more acute, more strongly curved outwards or downwards and inserted more dorsomedially on the gonocoxites in a large membranous field ringed by stout setae ( Figs. 4–5 View FIGURES 1 – 9 ; see also Zimmerman 1993, figs. 160, 176, 215, 227, 242). This type is indicated to be a modification of the first, as the conditions in Acherres , Amorphorhinus , Atychoria , Euomella and Pseudonotonophes are slightly transitional in that their styli are positioned more dorsally and the membranous area is anterodorsally demarcated by some larger but irregular setae. A third type of amycterine ovipositor occurs in Acantholophus , Anascoptes Pascoe , Cubicorhynchus , Hyborrhinus Marshall, Molochthus Pascoe , Neohyborrhynchus Ferguson and Parahyborrhynchus Ferguson , in which the styli are generally straight, blunt and carry an inner basal tooth or large prong and are more or less drawn into the mesal side of the distal gonocoxites ( Figs. 8–9 View FIGURES 1 – 9 ; see also Zimmerman 1993, figs. 89, 182). The basal tooth is smallest in Hyborrhinus and strongest in Cubicorhynchus , in which the styli are antler-like to strongly double-pronged ( Fig. 9 View FIGURES 1 – 9 ). These three types of amycterine ovipositor indicate that the traditional subdivision of the group, into subtribes Amycterina and Euomina, cannot be upheld and that rather Acantholophus and allied genera may form a subgroup distinct from the others. Some external features, such as the conspicuous spine above the eye for which Acantholophus was named, support such a grouping but are in need of more comprehensive study.

The Amycterini currently number 39 genera and 408 species, but at least one new genus and a number of undescribed species are identified in Australian collections. Their biology is generally poorly known, but Howden (1986) provided a most useful summarising account of adult and larval hostplants, oviposition behaviour and pupation sites for a range of species and May (1994) described preimaginal stages for 16 species. Porch (2009) added a note on the host and feeding behaviour of Tetralophus View in CoL . Circumstantial evidence indicates that eggs are laid by means of the specialised ovipositor into the soil, where the larvae feed ectophytically on underground stems, bulbs, tubers, rhizomes and perhaps roots of their hostplants. Only monocotyledons are reported as larval hosts, spanning both tough grasses and succulent lilies and also grasstrees ( Xanthorrhoea ). Pupation occurs in the soil near the larval hostplants.

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.

|

Kingdom |

|

|

Phylum |

|

|

Class |

|

|

Order |

|

|

Family |