Thryonomys swinderianus (Temminck, 1827)

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6617684 |

|

DOI |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6617619 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/396E8799-0566-FFAE-DB85-5C48F739FD0B |

|

treatment provided by |

Carolina |

|

scientific name |

Thryonomys swinderianus |

| status |

|

1.

Greater Cane Rat View Figure

Thryonomys swinderianus View in CoL

French: Grand Aulacode / German: Grof 3e Rohrratte / Spanish: Rata de canaveral grande

Other common names: Cutting-grass, Grass Cutter, Marsh Cane Rat

Taxonomy. Aulacodus swinderianus Temminck, 1827 ,

no type locality given.

Originally placed under the new genus Aulacodus and then discarded because the name had been already used for a Coleoptera. Monotypic.

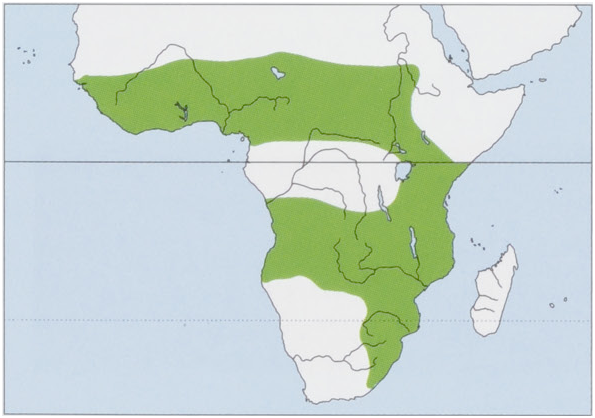

Distribution. Widely distributed throughout sub-Saharan Africa, from Senegal to Sudan and S to E South Africa. It is absent from the Horn of Africa, the Central African tropical forest basin, and the arid areas of Namibia, Botswana, and South Africa. View Figure

Descriptive notes. Head-body 630-770 mm; tail 160-195 mm; weight 3.2-5.2 kg (males) and 3.4-3.8 kg (females), but up to near 9 kg (some males from eastern Africa). Cane rats are the third largest rodent in Africa (only surpassed in size by the Cape ( Hystrix africaeaustralis) and the Crested (H. cristata) porcupines. The Greater Cane Rat has a massive blunt head, with a squarely cut muzzle, slender andshort facial vibrissae (less developed than in the Old World porcupines), and short round ears. Thick and compact bodyis covered byspiny, coarse, and stiff pelage of brown-yellowish and gray hairs that vary depending on its habitat. Lips, chin, and throat are often white, with a brown pelage speckled with white on ventral surface. Tail is scaly and has short, sparse hairs. Skin is very weak andtears easily, but it also heals easily. Legs are strong, andfeet are perissodactyl—different from any other hystricognathous rodent. Forefoot has a minute pollex. Morphologyof paws plays an essential role in feeding because they are specially adapted to hold pieces ofgrass. Second, third, and fourth digits are short and thick and end in long strong claws. Second and fourth digits are subequal in size and shorter than third digit, andfifth digit is greatly reduced andis much smaller than the fourth. Hindfeet lack first digits; otherwise, their digits are similar in morphology, longer than those offorefeet, and have with long heavy claws. Upper and lower incisors are covered on the front by an orange enamel layer; they are broad, strong, and sharp and are used exclusively to cut tough vegetation, not to fight. Upperincisors are deeply grooved longitudinally on outer surfaces. Cheekteeth are rooted; dental formulaisI11/1, C0/0,P 1/1, M 3/3 (x2) = 20. Tooth succession is relatively slow, with eruption of lower cheekteeth in advance of upper ones. The Greater Cane Rat has an encephalization quotient (0-4) higher than the African giant rats, rats, and rabbits, suggesting better memorystorage and ability to cope with new challenges, although below the average of 1 in mammals.

Habitat. Marshy areas, riverbanks, reed beds, long-grass savannas, and fields of sugarcane, maize, and guinea corn. The Greater Cane Rat depends on availability ofpreferred grasses; it does notlive in rainforests, dry deserts, or dry shrublands.

Food and Feeding. The Greater Cane Rat is a monogastric herbivore. It is a highly specialized grass eater, with morphological adaptations to deal with tough-stemmed grasses that need to be cut off close to the ground. When eating, it turns its head sideways to bring edges ofincisors in contact with the lowest part of the stem. The way in which Great Cane Rats cut stems is an inherited pattern that juveniles do not need to learn; however, the technique that cane rats use to cope with heads ofseeds, holding the stem in one paw and pushing the head into the mouth to remove the seeds, has to be learned and perfected. The Greater Cane Rat mainly feeds on stems of Panicoideae grasses (Megathyrsus, Pennisetum, Setaria, Echinochloa, Sorghastrum, and Hyparrhenia), particularly common guinea grass (Megathyrsus maximus) and elephant grass (Pennisetum purpureum). They also eat goosegrass (Eleusine indica) and, to a lesser extent, Egyptian crowfoot grass (Dactyloctenium aegyptium). They prefer thinner and softer parts ofgrasses, which are eatenfirst, andif food is abundant, they discard tough lower parts ofstems. Gut bacteria facilitate digestion of grasses. The Great Cane Ratis coprophagous and takes pellets directly from the anus and masticates them intensively for c.40 seconds. In captivity,it prefers sweet potato ( Ipomoea batatas, Convolvulaceae ) over than other tubers. Although the Greater Cane Rat does not burrow, it is able to scratch the soil aside to expose succulent underground stems or roots, which are a source of water andfood during the dry season when greengrassis scarce. When feeding, male Greater Cane Rats are more aggressive than females, and typically, females start eating only after males are finished. The Greater Cane Rat meets its mineral requirements by eating soil. From time to time, it gnaws rocks, bones, or ivory, apparently to sharpen its incisors rather than to procure nutrients.

Breeding. Details on reproduction of the Greater Cane Rat are mostly known from studies of captive individuals or dead carcasses bought on markets; reproductive biology and breeding behavior are expected to be similar in the wild. Greater Cane Rats start breeding at ¢.5 months old. Estrous cycle is erratic, and length varies significantly among individuals, suggesting that ovulation occurs after externally derived stimulus. Breeding seasons of Greater Cane Rats vary depending on seasonality of rainfall. In Ghana, they breed throughout the year, but in other places of western Africa, juveniles have been reported only from mid-October to the beginning ofJanuary. Gestation is long, typical of hystricomorph rodents (148-157 days). The Greater Cane Rat produces two litters each year under favorable conditions, with 1-8 young (most often 2-6). In some countries of western Africa (e.g. Benin and Togo), litters of up to 11-12 young have been reported. Greater Cane Rats are polygamous. A male wagsits tail when courting a female to indicate that its approach is not aggressive. If a female is attracted to these actions,the pair will rear up, touch noses, and copulate. As in most hystricomorph rodents, young are precocious at birth, with eyes and ears open and fully furred, and they can follow their parents less than an hour after birth. Females have three pairs of teats that are located high on sides of the abdomen, so they can feed their young while standing or lying on their bellies. Young are weaned in c.4 weeks. Postnatal growth of Greater Cane Rats is slow. Weight of young at birth is 76-207 g, inversely related to litter size, and on average 164 g for males and 158 g for females. When ¢.5 months old, average weight is 1-5 kg for males and 1-3 kg for females; it doubles during the next five months. Young stay with their parents until they reach their sexual maturity at ¢.5 months old. At this age, the dominant male becomes aggressive toward young males, and dominant young males become aggressive toward their brothers. Young females are not bothered. The Greater Cane Rat can live c.4 years in captivity.

Activity patterns. Greater Cane Rats are mainly nocturnal, but they can be active during daytime. They do not dig holes or burrows orlive in tunnels. Depending on ambient temperatures, they rest either on top of or under heaps of grass. Their shelters are typically located in matted vegetation, but when there is a lack of cover or a high density of predators, they shelter in abandoned holes of Aardvarks (Orycteropus afer) and porcupines, rock crevices, or holes caused by water erosion alongside river banks. If none of these sites are available, they can excavate shallow burrows. At night, the Greater Cane Rat follows its well-defined path through dense reeds and grass that often leads to water. It is an excellent swimmer, has good eyesight, a keen ear, and a sharp sense of smell. It also has a good sense of orientation. Great Cane Rats often feed in groups; when relaxed and eating, they make soft, grunting sounds. Waste products from feeding and scattered piles of feces suggest their presence. Greater Cane Rats are alert and anxious about every unusual noise, smell, or sudden movement. When disturbed, they hide wherever they can find shelter; they run away, then stop and stand motionless. Whenever possible, they run through dense vegetation with sudden and amazing speed toward water. Greater Cane Rats have alarm signals that consist of a whistle and a thump on the ground with hindfeet. They are amicable and greet, groom, huddle, play, and follow each other. Typically, when two individuals meet, one will turn its head and be briefly groomed under the chin by the other in a sort of greeting ceremony. Grooming is mutual: one individual approaches another, groomsit for a while around ears and throat and then placesits head in front of the mouth of the other’s to solicit grooming. Aggression by Greater Cane Rats is generally not harmful because they fight in a very stylized manner, gauging each other’s strength and pugnacity. Instead of using their extremely dangerous incisors, they engage in a snout-to-snout pushing duel, a technique used by young when they play. When caught, Greater Can Rats desperately try to escape but without biting.

Movements, Home range and Social organization. The Greater Cane Rat travels at night through trails in reeds and grass, often to water. It is not strictly gregarious, but it usually lives in small family groups of up to c.12 members that can be close to other family groups forming some type of colony. Only males live alone. Gregarious behavior is common among herbivores, such as Greater Cane Rats, that live in areas where resources are not too scarce. Group vigilance reduces the chance of being caught by a predator. A family group is of the harem type, consisting in a male, his females, and their young. Males are intolerant of one another and their own male offspring after they reach sexual maturity. Rivals are driven away, and it is not clearif they remain in the periphery of the group or become truly solitary. Within the group, female Greater Cane Rats show mutual tolerance. When a family group is on the move, one of the parents, usually the male, leads the group. Therefore, specimens seen in markets are often males because leaders are more prone to being trapped. Greater Cane Rats seem to be hierarchically organized, with a dominant male that use nose-to-nose pushing to consolidate its position. There is also a submissive behavior when subordinate members of the group approach dominant ones. Young Greater Cane Rats tail-wag when sniffed, sometimes when merely approached from the rear by an adult or when taking food from an adult. This signal seems to be a friendly or appeasing gesture that points to social interrelationships beyond those between a male and a female for mating and between a female and her young during the lactation period.

Status and Conservation. Classified as Least Concern on The IUCN Red List. Meat ofthe Greater Cane Ratis very popular due to its high protein content (49%). Hunters use poisonous traps, guns, dogs, or fire to smoke them out. This may also be detrimental to health of consumers (meat from poisoned individuals is toxic) or to the environment (bush fires often get out of control, burning nearby farmlands and often forcing Greater Cane Rats to move to another area). The best solution to cope with these problems is breeding Greater Cane Rats in captivity, which also benefits the economy of the area. Nevertheless, farmers of Great Cane Rats faces several challenges, including theft of captive individuals, prohibitive start-up costs and ongoing husbandry, and competition with hunters driving down market prices of Greater Cane Rats. Great Cane Rats are not easy to maintain under husbandry and require special handling skills; in some places, experienced farmers train other people to raise Greater Cane Rats.

Bibliography. Addo (2002), Addo et al. (2007), Adu (2003), Adu et al. (2000), Anang et al. (2011), Antoh et al.

(2005), Asibey (1974a, 1974b), Baptist & Mensah (1986), Bergman (2012), Byanet & Dzenda (2014), Cox et al.

(1988), Ewer (1968, 1969), Fadeyi et al. (2011), Granjon & Duplantier (2009), Happold (2013b), Hayssen et al.

(1993), Hoffmann (2008a), Kingdon (2015), Kleiman (1974), Kraatz et al. (2013), Lopez-Antonanzas et al. (2004), Mensah & Okeyo (2006), Nowak (1999a), NRC (1991), Opara (2010), Pocock (1922), Shortridge (1934a), Skinner & Chimimba (2005), Van der Merwe (1999, 2000, 2004b), Van der Merwe & Bronner (2007), Van der Merwe & Van Zyl (2001), Wesselman (1984), Wesselman et al. (2009), Winkler (2003), Woods (1976).

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.

|

Kingdom |

|

|

Phylum |

|

|

Class |

|

|

Order |

|

|

SubOrder |

Hystricomorpha |

|

InfraOrder |

Hystricognathi |

|

Family |

|

|

Genus |

Thryonomys swinderianus

| Don E. Wilson, Thomas E. Lacher, Jr & Russell A. Mittermeier 2016 |

Aulacodus swinderianus

| Temminck 1827 |