Batrachosauroididae, Auffenberg, 1958

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/10.4202/app.00926.2021 |

|

DOI |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.10988588 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/48028786-C84B-FFC3-FCFA-F900FD34A898 |

|

treatment provided by |

Felipe |

|

scientific name |

Batrachosauroididae |

| status |

|

Batrachosauroididae indet. (probable new genus and species)

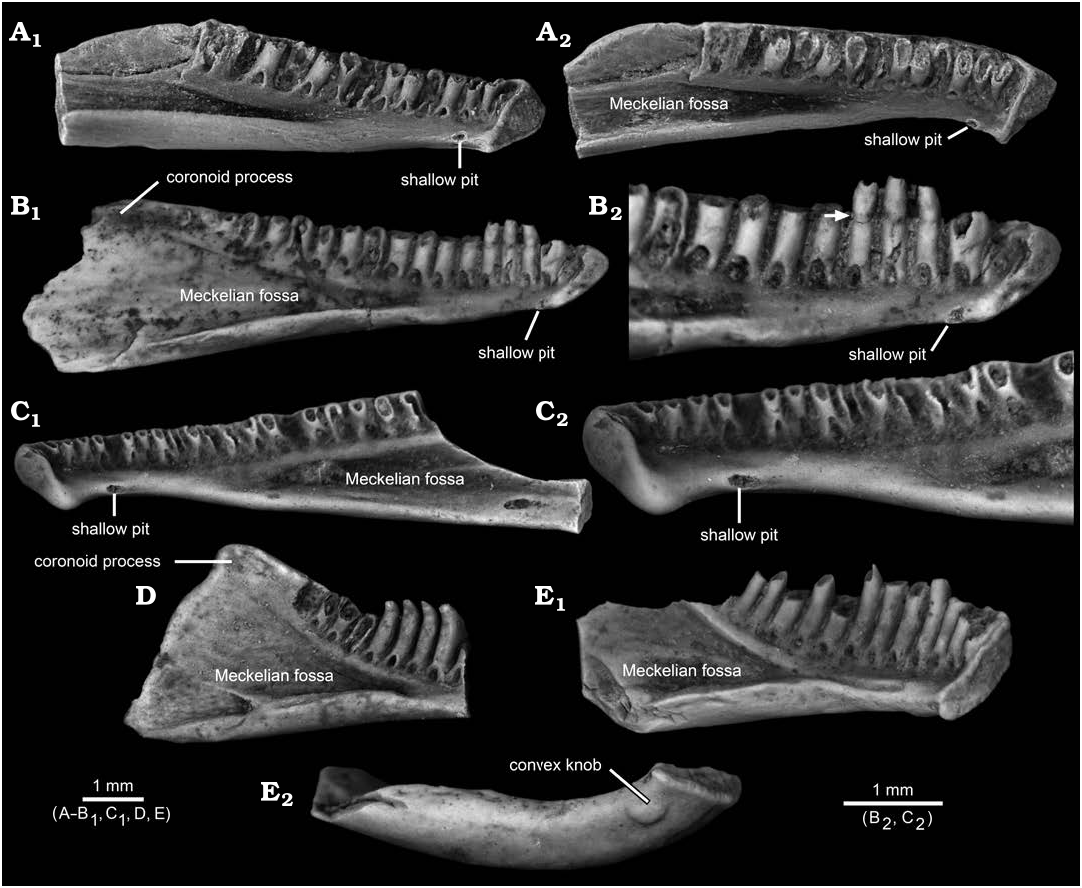

Figs. 1–3 View Fig View Fig View Fig .

Material.— AMNH FARB 22965 , incomplete left dentary from upper part of Lance Formation; upper Maastrichtian ; Bushy Tailed Blowout locality ( UCMP locality V-5711), type area of Lance Formation, Niobrara County, eastern Wyoming, USA .

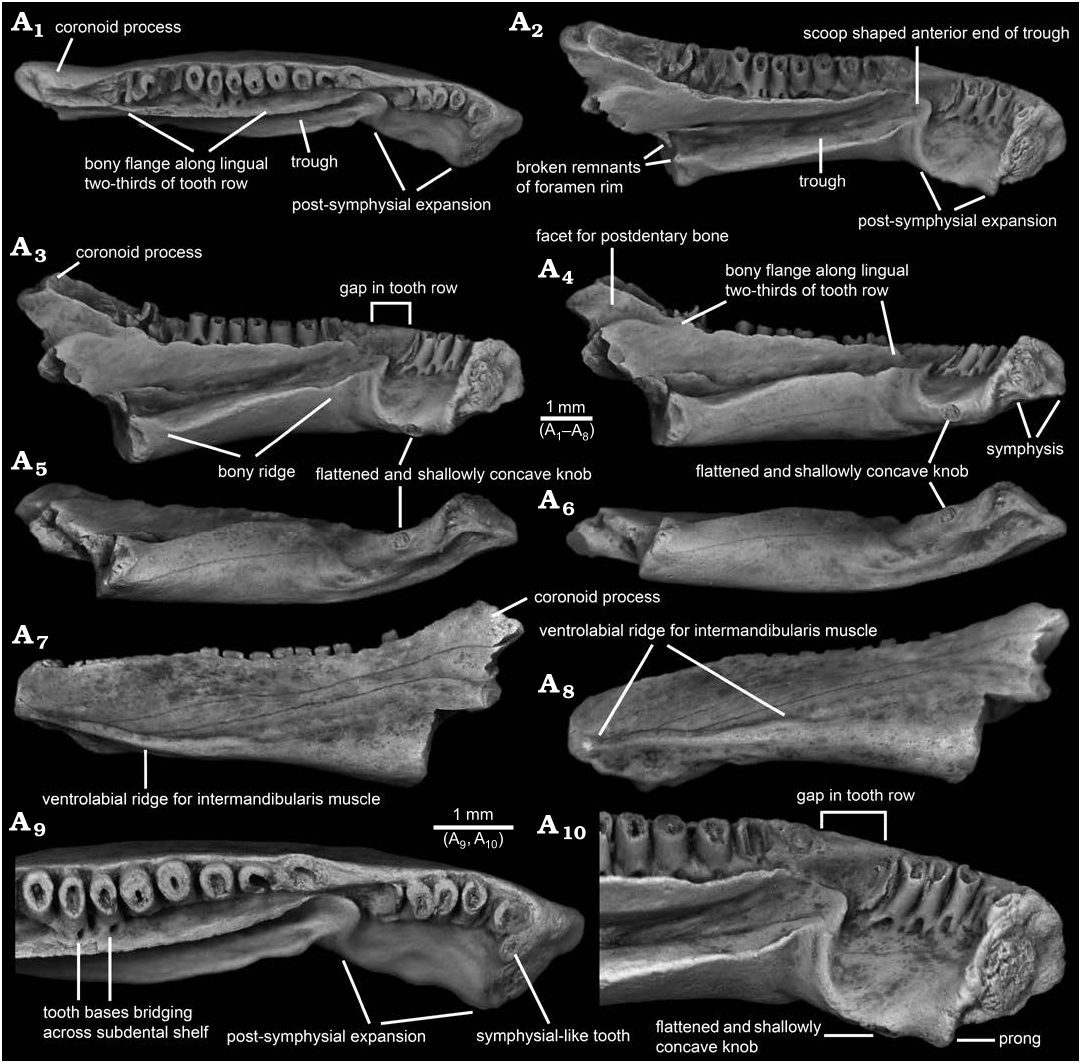

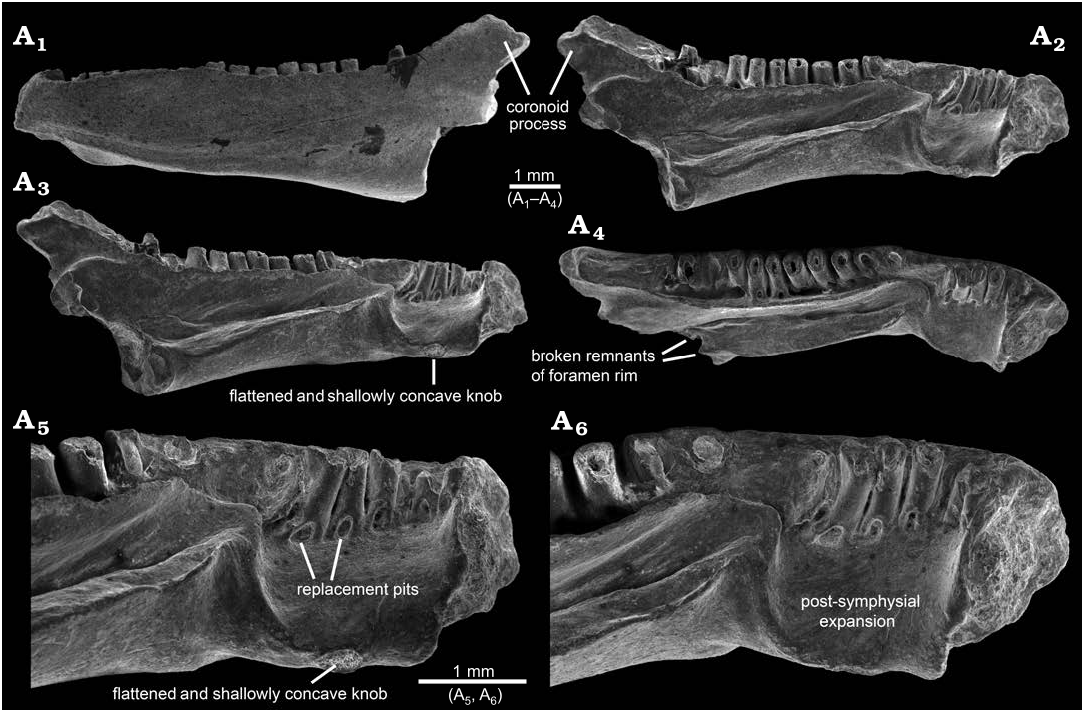

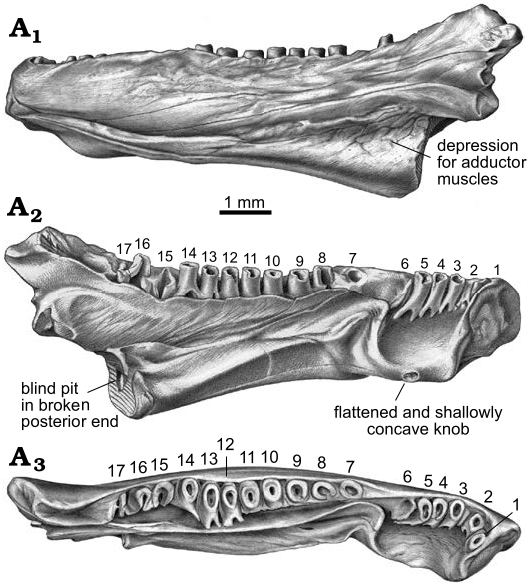

Description.—AMNH FARB 22965 ( Figs. 1–3 View Fig View Fig View Fig ) is a posteriorly incomplete left dentary that is broken through the posterior portion of its coronoid process and preserves 17 tooth positions. The dentary is relatively robust in construction and moderately elongate, measuring 10.0 mm in total preserved length (maximum horizontal distance between anterolabial corner of symphysis and posteriormost preserved end of coronoid process).

In lingual or labial outline ( Figs. 1A View Fig 3 View Fig , A 7, 2A 1, A 2, 3A 1, A 2), AMNH FARB 22965 resembles a horizontally elongate, irregular quadrilateral. The dentary is moderately deep, expanding from a maximum anterior depth of 1.5 mm (vertical distance between dorsal and ventral edges of symphysis) to a maximum posterior depth of 3.8 mm (vertical distance between apex of coronoid process and broken posteroventral corner of bone). Compared to the shallower anterior end, the posterior portion of the dentary is expanded both dorsally and ventrally. The anteriormost end of the bone is formed by the labial rim of the symphysis. That margin is blunt in labial or lingual outline, with its lower two-thirds straight and slightly tilted posteriorly, whereas its upper one-third is broadly convex and tilted more posteriorly. Proceeding posteriorly from the low and anteroposteriorly short bulge that represents the dorsal rim of the symphysis, the dorsal margin along much of the pars dentalis is shallowly sinuous in labial or lingual outline. A short stretch of the dorsal margin adjacent to the second tooth position is shallowly concave. Beginning adjacent to the third tooth position, the dorsal edge ascends posteriorly in a low and nearly straight line to the apex of a low rise located about one-third of the distance along the ramus or adjacent to the seventh tooth position. From that low apex, the dorsal edge continues posteriorly as a shallowly concave arc to a point about two-thirds of the distance along the ramus or adjacent to the thirteenth tooth position. From there, the dorsal margin continues posteriorly and curves upwards at a steeper angle of about 20° in a gently concave arc and terminates behind the tooth row in a pronounced coronoid process. The ventral edge of the dentary descends at a shallow angle posteriorly from the symphysis and is weakly sinuous in lingual and, especially, labial outline. As best seen in labial view ( Figs. 1A View Fig 7, 2A 1, 3A 1), two ventral bulges are present behind the symphysis: the shallow and more anterior bulge is the ventral rim of the symphysis, whereas the larger, more posterior, and lingually displaced bulge is the ventral portion of the linguoventrally-directed, post-symphysial expansion (see below). Behind those bulges, the ventral edge of the dentary descends in a shallow, ventrally concave arc at about 10° below horizontal, before abruptly terminating where the posterior end of the dentary is broken. Extrapolating from the ventral profile along the preserved portion of the bone suggests that the missing, more posterior portion was even deeper when the dentary was intact. The posterior end of the specimen is broken in a jagged line that dorsally begins along the posterior base of the coronoid process and extends anteroventrally through the upper two-thirds of the bone, then continues ventrally through the lower one-third of the bone as a vertical break approximately in line with the posterior end of the tooth row.

In dorsal or ventral view ( Figs. 1A 1 View Fig , A 6, 3A 3), AMNH FARB 22965 is shallowly arcuate or convex labially and is shallowly bent at the level of the third tooth position. Posterior from the symphysis and relative to the sagittal plane (as demarcated by the symphysial surface), the long axis of the ramus initially extends labioposteriorly at about 60° for a short distance. At the level of the third tooth position, the orientation changes and the remainder of the ramus extends posteriorly at a shallower angle of about 30° relative to the sagittal plane. The dentary is moderately wide labiolingually, having a maximum width of 1.7 mm (measured horizontally and perpendicular to the long axis) at approximately the anteroposterior mid-point of the specimen or in line with the eleventh tooth position.

The lingual surface of AMNH FARB 22965 ( Figs. 1A View Fig 2 – A View Fig 4 View Fig , A 9, A 10, 2A 2 –A 6, 3A 2) is complex and exhibits several unusual features for a salamander, most notably (i) a pronounced post-symphysial expansion occupying about the anterior one-third of the tooth-bearing portion of the dentary, (ii) a prominent trough extending along the posterior two-thirds of the ramus and curving upwards along its anterior portion towards the marginal tooth row, (iii) approximately at the boundary between those first two features, an apparent gap in the marginal tooth row, and (iv) lack of an obvious Meckelian fossa or groove. Approximately in line with the gap in the tooth row and most obvious in dorsal view ( Figs. 1A 1 View Fig , A 9, 3A 3), the lingual surface of the dentary is labially constricted or pinched and, at that point, is just 1.2 mm wide labiolingually (measured horizontally and perpendicular to the long axis of the ramus). Between this constricted zone and the symphysis, the subdental shelf and its shallow, underlying corpus dentalis are broadly expanded lingually and ventrally to form a prominent shelf that I informally call the “post-symphysial expansion”. This post-symphysial expansion has a maximum labiolingual width of 1.5 mm (measured horizontally and perpendicular to the long axis of the ramus at the level of the fourth tooth) and it extends ventrolingually at about 40° degrees below horizontal. The post-symphysial expansion is dorsoventrally deepest labially and shallowest lingually. Its dorsal surface is broadly convex labiolingually, essentially flat anteroposteriorly, and shallowly pitted, and its labialmost portion grades into the pars dentalis below the bases of the anteriormost six teeth. The anterolingual corner of the post-symphysial expansion extends slightly beyond the ventroposterior rim of the symphysis, as a short, blunt, and prong-like projection (best seen in dorsolingual view: Figs. 1A View Fig 2 View Fig , A 10, 2A 6). The lingual rim of the post-symphysial expansion is broadly convex ventrolingually in transverse view and, midway along its length, bears a small, knob-like structure (“flattened and shallowly concave knob” in Figs. 1A View Fig 3 –A View Fig 6, A 10, 2A 5, 3A 2) consisting of a raised rim that is elliptical in outline, with its long axis extending anteroposteriorly. The surface enclosed by that raised rim is shallowly bowl-shaped and has a slightly roughened texture. The posterior rim of the post-symphysial expansion curves dorsally and labially, grading into the anterior end of the prominent trough described below.

Behind the post-symphysial expansion is a prominent bony ridge ( Figs. 1A View Fig 2 –A View Fig 4 View Fig , 2A 2 –A View Fig 4 View Fig , 3A View Fig 2 View Fig ) that is moderately deep and wide, and extends anteroposteriorly along the ventral part of the lingual face of the ramus. This bony ridge is potentially homologous with the “corpus dentalis” of Vasilyan et al. (2013), but for the purposes of this description I refer to it informally as the “bony ridge”. Regardless of its identity, this bony ridge is deepest anteriorly and becomes shallower posteriorly, before abruptly ending where the bone is broken. The lingual surface of the bony ridge is broadly convex in transverse view and tilted slightly ventrally, with its lower edge grading into the ventral surface of the ramus. The dorsal surface of the bony ridge is developed as a lingually broad shelf that is broadest midway along its preserved length and its surface is shallowly convex from side-to-side. Its dorsolingual edge is developed as a keel-like and low rim anteriorly, rendering the shelf more gutter-like along that portion, whereas posteriorly the dorsolingual edge becomes lower and blunter, rendering the shelf flatter along that portion. The junction between the labial portion of the shelf and adjacent lingual wall of the ramus is shallowest and nearly perpendicular along its central portion, but deepens to form a narrow trench more posteriorly and, especially, anteriorly. Dorsal from that junction, the lingual wall of the ramus rises dorsally and curves slightly lingually, with its dorsalmost portion developed as a labiolingually narrow flange ( Figs. 1A 1 –A View Fig 4 View Fig , A 9, A 10, 2A 2 –A 4, 3A 2, A 3) that approximately parallels the posterior two-thirds of the tooth row. This narrow flange becomes shallower both anteriorly and posteriorly; the flange anteriorly terminates just behind the gap in the tooth row, whereas posteriorly it extends posterodorsally as a low rim along the lingual edge of the anterior face of the coronoid process. Collectively, the shelf-like dorsal surface of the bony ridge and adjacent lingual wall of the ramus form an elongate, lingually broad trough ( Figs. 1A 1 –A View Fig 4 View Fig , A 9, A 10, 2A 2 –A 6, 3A 2, A 3) that extends anterodorsally and slightly lingually in a shallow arc, to just past the constricted zone, at which point the trough terminates in a well-defined, scoop-shaped structure below, and lingual to, the gap in the tooth row. The anterior rim of this scoop, in turn, ventrally gives rise to the above-mentioned low ridge that curves ventrolingually and anteriorly, before grading into the posterior rim of the post-symphysial expansion. At its broken posterior end and adjacent to the trough, the dentary bears a pair of small, hook-like projections, one extending dorsally from the dorsolingual corner of the bony ridge and one extending lingually from the lingual wall of the ramus just above the dorsal surface of the bony ridge, that partially enclose a small, semi-circular opening ( Figs. 1A View Fig 2, 2A View Fig 4 View Fig ). These projections may be the broken rim of a foramen or canal. No obvious Meckelian fossa or groove is present below or immediately behind the tooth-bearing portion of the ramus.

As best seen in lingual and dorsal views ( Figs. 1A 1 –A View Fig 3 View Fig , A 9, A 10, 2A 2 –A 6, 3A 2, A 3), the pars dentalis is moderately high and 17 tooth positions are preserved on AMNH FARB 22965. Suspected damage to the dorsal surface of the bone at the junction between the coronoid process (see below) and posterior end of the tooth row raises the possibility that an additional tooth position may have been present there in life. The preserved tooth positions (numbered in Fig. 3A View Fig 2 View Fig , A 3 View Fig ) consist of ten relatively complete pedicels (i.e., preserving intact or nearly intact dorsal rims, at positions 1, 3–5, 9–14), six fragmentary pedicles (at positions 2, 6, 8, 15–17), and one empty slot preserved as a shallowly bowl-shaped divot at position 7). No tooth crowns or replacement teeth are preserved. As argued below (see “Remarks”) I interpret the teeth as having been pedicellate. Tooth pedicels vary in their position, attachment, and form. In general, the pedicles are marginal in position, moderately pleurodont in attachment i.e., attached along most of their height to the adjacent bony wall of the dentary), closely spaced, perforated at their base by a lingual replacement pit, and have smooth walls that are subcircular to mesiodistally compressed. The first six teeth along the post-symphysial expansion are separated from the remaining 11 tooth positions by a short gap, located about one-third of the distance along the tooth row and equivalent in length to the diameters of two or three pedicles. When examined visually using a binocular microscope (e.g., Fig. 1A View Fig 10), this toothless interval does not seem to be an artefact, because the exposed lingual wall of the pars dentalis appears smooth and lacks any trace of tooth bases or slots. However, scanning electron micrographs ( Fig. 2A View Fig 5 View Fig , A 6) indicate that same surface is slightly roughened, which leaves open the possibility that weakly attached teeth may have been present in life, but were detached post-mortem. The second to seventeenth teeth are clearly marginal, in that their pedicels are aligned with each other in a gently curved row that parallels the pars dentalis and each pedicel is labially attached to the lingual face of the pars dentalis. By contrast, when viewed from above, the first tooth pedicel ( Fig. 1A View Fig 9) is displaced or shifted slightly lingually, by about one-half the diameter of its pedicel, relative to the second tooth, and even more so relative to the arc described by the remainder of the tooth row. Also, the attachment of the first tooth differs in being approximately perpendicular to the others, with its pedicel attached mesially to the posterior face of the dorsal rim of the symphysis. Finally, the first tooth pedicel is slightly smaller and more noticeably compressed mesiodistally relative to the other pedicels. Based on the position, attachment, and form of its pedicel, the anteriormost tooth potentially may be a symphysial tooth. Tooth pedicels in front of the gap in AMNH FARB 22965 are completely exposed lingually, whereas those behind the gap are set into a deep gutter ( Figs. 1A 1 View Fig , A 2, 2A View Fig 4 View Fig , 3A View Fig 2 View Fig , A 3 View Fig ). The labial wall of that gutter is formed by the pars dentalis, whereas the lingual wall is formed by the flange of bone described in the preceding paragraph that extends dorsolingually from the lingual wall of the ramus above the bony ridge. Bases of the adjacent twelfth and thirteenth tooth pedicels bridge the dental gutter and attach along the inner surface of the lingual wall of the gutter ( Fig. 1A View Fig 9), thereby roofing an anteroposteriorly short canal below. Pedicels at positions 1–6 and 12–14 have walls that are relatively thinner and more compressed mesiodistally, whereas the remaining pedicels are stouter and more subcircular in cross section. Pedicels along the post-symphysial expansion also are slightly recurved in lingual view, whereas those behind the gap are more nearly vertical.

AMNH FARB 22965 bears a pronounced coronoid process ( Figs. 1A 1 –A View Fig 4 View Fig , A 7, 2A 1 –A 4, 3) that is triangular in labial or lingual view and relatively high (1.0 mm high, measured as vertical height between the apex of the process downwards to the level of the thirteenth tooth position or where the dorsal edge of the ramus begins to curve dorsally and grades into the coronoid process). The coronoid process also is relatively robust, measuring 0.8 mm in maximum labiolingual width just below its apex. The coronoid process has the same roughened labial texture described below for the remainder of the bone. By contrast, the lingual surface of the coronoid process is smooth and indented by a broad, shallow facet that is demarcated ventrally by a dorsally convex rim; this facet presumably was for overlapping contact with a postdentary bone, most likely the prearticular. The inclined, anterior face of the coronoid process is indented by an anteroventrally-posterodorsally elongate groove that is shallowly concave from side-to-side and is bordered both labially and lingually by a low and narrow, yet distinct, bony rim. The posterior two-thirds of this groove has a slightly roughened texture and, thus, appears to preserve its natural surface. More anteriorly, however, the groove has a slightly jagged and shiny texture, suggesting its original external surface has been broken away along this portion of the coronoid process and, perhaps, the posteriormost end of the tooth row. Along its preserved length, the declined, posterior face of the coronoid process is smooth and shallowly concave from side-to-side, but lacks the distinct labial and lingual rims seen along the anterior face. Posterior breakage means the full posterior extent and form of the coronoid process are unknown.

The labial surface of AMNH FARB 22965 ( Figs. 1A View Fig 7, A 8, 2A 1, 3A 1) is broadly convex, almost flat, in transverse profile and has a weakly roughened texture created by scattered pits that are small, extremely shallow, and irregular in outline. A few hairline cracks or grooves extend anteroventrally-posterodorsally at a shallow angle across the labial surface. Foramina mentalia (= external foramina) are lacking. A low, yet distinct ridge extends anteroposteriorly along the ventrolabial margin of the anterior one-half of the ramus. This ridge is labially convex in transverse profile along its anterior and posterior portions, but more keel-like along its central portion. The dorsal margin of the ridge is paralleled by a narrow, shallow groove. More posteriorly, the ventral portion of the labial face of the dentary is indented by a broad, shallow, and posteriorly deepening, anteroposterior depression. Comparisons with extant salamanders (e.g., Francis 1934; Özeti and Wake 1969; Larsen and Guthrie 1975; Erdman and Cundall 1984; Duellman and Trueb 1986; Lorenz Elwood and Cundall 1994; Kleinteich et al. 2014) suggest that the more anterior ridge and groove complex and the more posterior depression served as attachments for, respectively, intermandibularis and adductor muscles.

In ventral view ( Fig. 1A View Fig 5 View Fig , A 6), the above-described knob-like structure on the ventrolingual portion of the post-symphysial expansion and the elongate ventrolabial ridge for attachment of intermandibularis muscles are evident along the anterior portion of AMNH FARB 22965. Otherwise, the ventral surface is relatively smooth and lacks foramina, pits, or a ventral keel. In transverse profile, the ventral surface of the post-symphysial expansion is shallowly concave across the anterior portion and flatter across the posterior portion. Behind that region, the preserved ventral surface of the ramus is broadly convex in transverse profile.

The symphysis of AMNH FARB 22965 ( Figs. 1A View Fig 2 –A View Fig 4 View Fig , A 10, 2A 2 –A 6, 3A 2) is preserved intact. It is subtriangular in outline (best seen in Fig. 1A View Fig 4 View Fig ), being deepest anteriorly and with a broadly convex anterior margin, and tapering to a blunt point linguoventrally. Its articular face is relatively unelaborated and nearly flat. An outer rim of relatively smooth bone encloses a central portion that is subcircular in outline and has a roughened and shallowly convex surface, presumably for ligamentous contact with the opposite mandible.

The posterior end behind and below the coronoid process is missing from AMNH FARB 22965, meaning little can be said about the form and extent of the area for attachment of postdentary bones, aside from suggesting that it was deep and robust. In keeping with the robust build of the specimen, its broken posterior surface ( Figs. 1A View Fig 4 –A View Fig 6, 2A 3, A 4, 3A 2) is relatively wide labiolingually, with a maximum width of 1.4 mm (measured horizontally across the broken dorsal edge of the bony ridge). As described above, what appear to be the broken remnants of the rim of a foramen are preserved adjacent to the broken posterior end of the bony ridge. The broken posterior surface exposes a divot in the central portion of the bony ridge—this appears to be a blind pit (i.e., having a solid interior surface and not penetrating anteriorly into the bone). Otherwise, the broken posterior surface of the dentary appears solid.

Remarks.—AMNH FARB 22965 is a unique dentary that exhibits a puzzling mix of features, including the following: along its posterior two-thirds, the lingual surface bears a prominent bony trough that extends anteriorly and curves upwards towards the marginal tooth row, below the trough is a well-developed bony ridge that may be homologous with the corpus dentalis, above the trough is a tall and narrow bony flange lingually paralleling the posterior two-thirds of the tooth row, and no obvious Meckelian fossa or groove is present; more anteriorly, the lingual surface is developed into a ventrolingually projecting shelf (here called the “post-symphysial expansion”) whose ventrolingual face bears a flattened and shallowly concave knob; the labial surface lacks foramina mentalia and anteriorly bears a prominent ventrolabial ridge; the symphysis is subtriangular in outline and its face is flattened; a prominent and robust coronoid process is present and bears a grooved anterior face; teeth are highly pleurodont and evidently pedicellate, the anteriormost tooth potentially is a symphysial tooth, and there is an apparent gap in the tooth row. To my knowledge, this suite of features has never been reported in a single dentary.

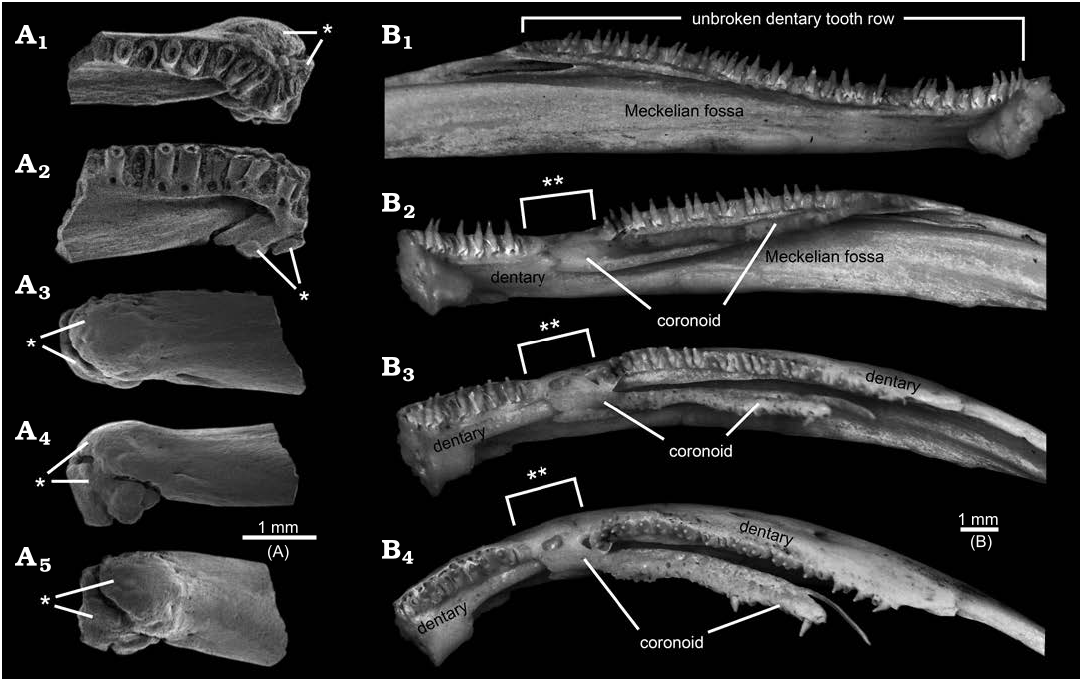

Some of the above-listed features may be anomalies or taphonomic artefacts. The bony trough along the lingual surface, the apparent gap in the tooth row, and lack of a Meckelian fossa or groove in AMNH FARB 22965 are strikingly peculiar and, to my knowledge, without precedent among amphibians. None of those features or any other portion of AMNH FARB 22965 shows gross distortions that imply trauma, unlike, for example, rare salamander dentaries from the Upper Cretaceous of Uzbekistan ( Skutschas et al. 2018: fig. 2) and Utah, USA ( Fig. 4A View Fig ) preserved with bony calluses resulting from healing of traumatic injuries. The observation that the dorsally curved anterior end of the trough coincides with the gap in the tooth row, suggests those two features may be linked. A potentially instructive skeleton in the TMP collections of the extant, neotenic salamander Ambystoma mexicanum ( Shaw and Nodder, 1798) , has a normal left dentary bearing an unbroken tooth row and a pathological right dentary in which the anterior end of the lingually placed coronoid anomalously overlaps onto the tooth-bearing region of the dentary, thereby creating a gap in the dentary tooth row ( Fig. 4B View Fig 1 View Fig and B 2 –B View Fig 4 View Fig , respectively). It is unclear whether a similar explanation might explain the gap in the tooth row for AMNH FARB 22965 or whether the adjacent, anterior end of the bony trough may have squeezed out the teeth. As noted in the preceding descriptive section, faint hints of a roughened lingual wall for the portion of the pars dentalis along the gap raise the possibility that teeth may have been loosely attached there, but were lost post-mortem. The identity and function of the lingual trough in AMNH FARB 22965 are unclear. The position of the trough is consistent with it being associated with the Meckelian fossa or groove, despite the discrepancies that (i) the anterior end of the trough opens dorsally, rather than extending anteriorly into the interior of the ramus or opening lingually and (ii) the trough projects lingually outwards from the ramus and for much of its preserved length runs along the dorsal surface of what might be the corpus dentalis (here called the bony ridge”), rather than being a labiolingually shallow fossa or groove within the subdental portion of the ramus see “Meckelian fossa” labelled in Fig. 5 View Fig ). What appear to be the broken remnants of a foramen at the posterior end of the bony trough suggest that a non-osseus structure (e.g., artery, vein, nerve, or cartilage) passed through that opening and extended along the floor of the trough. Alternatively or, perhaps, additionally, the trough may have either articulated with or been lingually covered by one or more mandibular bones. Conceivably the peculiar lingual trough and gap in the tooth row might be the result of a postdentary bone— the prearticular is a strong candidate, considering its proximity to the affected area—having abnormally overgrown the dentary, thereby both distorting the Meckelian fossa or groove and interrupting the tooth row. That scenario also would explain the striking absence of an obvious (i.e., normal) Meckelian fossa or groove, which in salamanders is developed within the lingual surface of the dentary, below and immediately behind the tooth-bearing portion of the ramus, as a labiolingually shallow depression that is deepest posteriorly and shallows anteriorly (see Figs. 4B View Fig , 5 View Fig ). Given the likelihood that the bony trough, gap in the tooth row, and lack of a Meckelian fossa or groove are anomalies, those are best set aside as potentially informative features.

As noted in the preceding descriptive section, the peculiar anteriormost tooth in AMNH FARB 22965 is reminiscent of a symphysial tooth. I qualify that identification, because unequivocal symphysial teeth that characterize many non-lissamphibian amphibians (e.g., the Permian amphibamid Doleserpeton annectens Bolt, 1969 ; Sigurdsen and Bolt 2010: fig. 6A) and the enigmatic African Late Cretaceous salamander Kababisha sudanensis Evans, Milner, and Werner, 1996 (Evans et al. 1996: text-figs. 3A, 4A, B), as well as the similarly-placed splenial teeth of many caecilians (e.g., Nussbaum 1977: fig. 2; Taylor 1977), differ in being completely separated lingually from the marginal tooth row and occur within a discrete pocket or groove. By contrast, the anteriormost tooth in AMNH FARB 22965 is only partially shifted lingually relative to the succeeding teeth (i.e., about one-half the diameter of its pedicel, relative to the second tooth) and it is not placed within a discrete depression. Considering its intermediate position, the anteriormost tooth in AMNH FARB 22965 seems better regarded as a marginal first tooth that has been anomalously displaced lingually. That displacement conceivably could have happened if the anterior portion of the tooth row was compressed by the anomalous overgrowth of the prearticular, which left insufficient space for the first tooth to develop in its normal position. Interestingly, in the pathological axolotl dentary with a somewhat similarly interrupted tooth row depicted in Fig. 4B View Fig , its anteriormost teeth retain their normal marginal positions. The remaining features in AMNH FARB 22965 are seen to varying degrees in other amphibian dentaries, meaning they appear to be normal structures and, thus, are potentially informative for assessing the taxonomic affinities of this unique dentary.

AMNH FARB 22965 originally was tentatively identified in the AMNH records as a dentary belonging to the albanerpetontid lissamphibian Albanerpeton nexuosum Estes, 1981 . That identification is understandable, considering that A. nexuosum is common within the Lance Formation (e.g., Estes 1964 [as jaws then referred to Prodesmodon copei Estes, 1964 ]; Gardner 2000a; Gardner and DeMar 2013) and that AMNH FARB 22965 superficially resembles dentaries of A. nexuosum (cf., Estes 1981: fig. 3H; Gardner 2000a: fig. 2) in size and robustness, in having moderate sized and highly pleurodont teeth, and in bearing a prominent ventrolabial ridge. However, AMNH FARB 22965 differs from all known albanerpetontid dentaries in lacking the stout and lingually projecting symphysial prongs that are autapomorphic for albanerpetontids, in lacking foramina mentalia labially and a distinctly gutter-like subdental shelf anteriorly, and in having teeth that are pedicellate, rather than being nonpedicellate as in albanerpetontids (e.g., Fox and Naylor 1982; Gardner 2001; Daza et al. 2020).

The inferred presence of pedicellate teeth in AMNH FARB 22965 is based on the observations that (i) many of its preserved tooth pedicels are similar in height, with their dorsal rims approximately in line with the dorsal edge of the pars dentalis, and (ii) where those dorsal rims are largely or completely intact, they are in an essentially horizontal plane and have a relatively smooth dorsal surface. That combination of features is indicative of teeth that exhibit some degree of pedicely (i.e., a poorly mineralized or fibrous zone of weakness between the shaft and crown: e.g., Parsons and Williams 1962; Duellman and Trueb 1986; Davit-Béal et al. 2007; Schoch 2014) and is routinely seen in extant and fossil amphibian jaws that have lost some or all of their crowns post-mortem, but retain their pedicels (e.g., Evans and Sigogneau-Russell 2001: text-fig. 1A, D; Evans and McGowan 2002: pl. 1: 5–7; Gardner 2003b: fig. 6D–F; Sigurdsen and Bolt 2010: fig. 6A). By contrast, breakage of nonpedicellate teeth can occur at any point along the basal-apical length of a given tooth, and those broken surfaces typically are irregular or jagged (e.g., Fig. 5D, E View Fig 1 View Fig ). Teeth having some amount of pedicely are considered derived within gnathostomes and are characteristic for many lissamphibians and some amphibamids (e.g., Parsons and Williams 1962; Bolt 1969; Milner 1993; Sigurdsen and Bolt 2010; Schoch 2014; Schoch and Milner 2014). AMNH FARB 22965 shows some resemblance to dentaries of amphibamids, such as Doleserpeton annectens (e.g., Bolt 1991; Sigurdsen and Bolt 2010: fig. 6A), in having pedicellate teeth, a symphysial-like (but probably anomalous) tooth, and expansion of the subdental shelf and corpus dentalis behind the symphysis, yet AMNH FARB 22965 differs in having relatively larger and far fewer marginal teeth (as few as 17 vs. at least 60 in D. annectens ), in lacking the multiple and more lingually placed symphysial teeth within a distinct depression or pocket and often arranged in a row in D. annectens , in being relatively more robust, and in lacking denticles and pits along the lingual surface below the pars dentalis. A further argument against regarding AMNH FARB 22965 as an amphibamid is that some 200 million years, according to the time scale of Ogg et al. (2016), separate the geologically youngest amphibamids (early Permian: see review by Schoch and Milner 2014) from AMNH FARB 22965 (latest Cretaceous).

Compared to non-albanerpetontid lissamphibians, AMNH FARB 22965 differs from dentaries of anurans (frogs) and resembles pseudodentaries of gymnophionans (caecilians) and dentaries of most caudates (salamanders) in having a relatively robust and complex ramus that bears teeth. The dentary of anurans is substantially different in being a slender, simple, and splint-like bone (e.g., Ecker 1889: fig. 21; Trueb 1993: fig. 6.16D, E) that primitively is toothless, with the sole exception of the extant Gastrotheca guentheri Fitzinger, 1843 , which appears to have re-evolved dentary teeth ( Wiens 2011; Paluh et al. 2021). The bony, single, and sometimes tusk-like odontoid developed near the anterior end of the mandible in some neobatrachian anurans (e.g., Lynch 1971: fig 15) is not a true tooth. Compared to AMNH FARB 22965, pseudodentaries of gymnophionans differ in having numerous foramina mentalia and, except for the Early Jurassic stem caecilian Eocaecilia micropodia Jenkins and Walsh, 1993 , the labial surface is roughened with ridges and grooves and a prominent coronoid process is absent; additionally, many caecilian taxa (including E. micropodia and the Early Cretaceous Rubricaecilia monbaroni Evans and Sigogneau-Russell, 2001) have one or more splenial teeth located within a distinct depression lingual to, and often paralleling, the anterior portion of the marginal tooth row (e.g., Nussbaum 1977: fig. 2; Taylor 1977; Trueb 1993; Evans and Sigogneau-Russell 2001: text-fig. 1; Jenkins et al. 2007: figs. 24–27). AMNH FARB 22965 compares most favourably to caudate dentaries in lacking the above-listed features typical of amphibamids, caecilians, and anurans and in exhibiting a combination of features considered distinctive for salamanders ( Estes et al. 1969; Naylor 1979; Fox and Naylor 1982), including: lack of a well defined Meckelian groove; poorly developed subdental shelf; symphysial surface dorsoventrally expanded and flattened; moderate sized and inverted U-shaped replacement pits in lingual bases of teeth; no foramina mentalia (present in some salamanders); and deep and, potentially, elongate region behind the tooth row (see Figs. 4B View Fig 1 View Fig , 5 View Fig ). The relatively smooth labial surface lacking ornament or a roughened texture and the presence of teeth in AMNH FARB 22965 also are typical for salamanders, although extant sirenids are unique among salamanders in having edentulous dentaries and upper jaws (e.g., Estes 1981; Duellman and Trueb 1986; Gardner 2003a: text-fig. 2F, 3D, H). Expansion of the anterior portion of the corpus dentalis behind the symphysis (= “post-symphysial expansion” here) is seen to varying degrees in some salamander dentaries (e.g., extant Amphiuma means Garden in Smith, 1821, and Amphiuma tridactylum Cuvier, 1827 ; Gardner 2003b: fig. 6D and F, respectively), although not as extreme as in AMNH FARB 22965.

The flattened and shallowly concave knob on the ventrolingual surface of the post-symphysial expansion in AMNH FARB 22965 has not, to my knowledge, previously been reported for salamander dentaries. Among comparative specimens available to me, I have identified similar structures only in referred, fossil dentaries belonging to two batrachosauroidid species: Opisthotriton kayi Auffenberg, 1961 , dentaries bear a shallow pit ( Fig. 5A–C View Fig ), with a roughened and shallowly concave interior surface enclosed by a slightly raised rim, located on the ventrolingual surface of the corpus dentalis behind the symphysis (i.e., approximately equivalent to the position of the flattened and shallowly concave knob on AMNH FARB 22965) and Prodesmodon copei dentaries bear a convex and smooth knob ( Fig. 5E View Fig ), located at approximately the same anteroposterior position as the knob on AMNH FARB 22965 and the pit in O. kayi , but positioned slightly more ventrolabially relative to both on the underside of the ramus. Although differing in details, overall similarities in the form and position of the post-symphysial knob/pit structures in AMNH FARB 22965, O. kayi , and Pro. copei suggest those are homologous. The presence of a similar feature in other batrachosauroidids is uncertain. Dentaries are unknown ( Naylor 1981) for Peratosauroides problematica (Naylor in Estes, 1981), the sole dentary described for Parrisia neocesariensis Denton and O’Neill, 1998 , lacks its symphysial end ( Denton and O’Neill 1998), and descriptions of dentaries for both species of Batrachosauroides ( Taylor and Hesse 1943; Estes 1969a, 1981, 1988; Hinderstein and Boyce 1977) and the three species of Palaeoproteus ( Herre 1935; Estes et al. 1967; Estes 1981; Vasilyan and Yanenko 2020) make no mention of a comparable structure. Considering that previous descriptions for O. kayi and Pro. copei dentaries made no mention of the symphysial knob/pit structure (e.g., Estes 1964, 1969a, 1975, 1981; Estes et al. 1969; Naylor 1979; Sullivan 1991; Tokaryk and Bryant 2004), more detailed examination of dentaries referable to other batrachosauroidids is needed to better assess the distribution of that feature within the family. The position and form of the symphysial knob/pit structure and comparisons with dissections of extant salamanders (e.g., Francis 1934; Özeti and Wake 1969; Larsen and Guthrie 1975; Erdman and Cundall 1984; Duellman and Trueb 1986; Lorenz Elwood and Cundall 1994; Kleinteich et al. 2014), suggest that bony structure may have served for attachment of the geniohyoideus or genioglossus muscles, which are hyobranchial levators that serve to pull the hyobranchial apparatus and tongue forward, actions that in aquatic feeding salamanders appear to help expel water out of the mouth after prey capture. Such a function is in keeping with the interpretation that batrachosauroidids were neotenic and aquatic salamanders (e.g., Estes 1969a, 1981; Milner 2000; Holman 2006).

Compared to named batrachosauroidids known by dentaries (i.e., all except for Peratosauroides problematica ), AMNH FARB 22965 shares four additional similarities with at least half of the recognized species, as follows: (i) anteroposterior depression present along posterior labial surface (relatively shallow depression shared with Opisthotriton kayi , Palaeoproteus miocenicus Vasilyn and Yanenko, 2020 , Parrisia neocesariensis , and Prodesmodon copei vs. relatively deeper depression in both species of Batrachosauroides and in Palaeoproteus gallicus Estes, Hecht, and Hoffstetter, 1967 , and Palaeoproteus klatti Herre, 1935 ); (ii) coronoid process present (well developed process shared with O. kayi , Pal. gallicus , Pal. klatti , and Pro. copei vs. process relatively lower and anteroposteriorly shorter in Batrachosauroides dissimulans Taylor and Hesse, 1945, and Pal. miocenicus ; condition unknown for other batrachosauroidids); (iii) pedicellate or subpedicellate teeth (shared with O. kayi , Par. neocesariensis , Pal. gallicus , and Pal. klatti vs. nonpedicellate teeth in Pal. miocenicus , Pro. copei , and both species of Batrachosauroides ); and (iv) lacks pronounced ventral projection of the symphysis (shared with O. kayi , Pro. copei , and all species of Palaeoproteus vs. projection present in both species of Batrachosauroides ; condition unknown for Par. neocesariensis ). AMNH FARB 22965 further resembles O. kayi , Par. neocesariensis , and Pro. copei in lacking foramina mentalia (vs. one or two foramina present in both species of Batrachosauroides and all three species of Palaeoproteus , except for some individuals of Pal. klatti ). The above suite of features, coupled with the observation that AMNH FARB 22965 shows no compelling resemblances to dentaries belonging to other salamander families ( Amphiumidae , Proteidae , Scapherpetidae, and Sirenidae ) known from the latest Cretaceous of the North American Western Interior (e.g., Estes 1964, 1981; Gardner 2003a, b), support assigning AMNH FARB 22965 to Batrachosauroididae .

AMNH FARB 22965 differs from all other batrachosauroidids in having a lingual bony flange paralleling the posterior two-thirds of its tooth row and a prominent post-symphysial expansion. AMNH FARB 22965 may also be unique among batrachosauroidids in having the anterior face of its prominent and robust coronoid process excavated by an anteroposterior groove that is bracketed labially and lingually by a narrow ridge vs. same surface is narrow and keel like in Opisthotriton kayi and Prodesmodon copei , whereas in a referred dentary of Palaeoproteus gallicus depicted by Estes et al. (1967: fig. 3) that surface is similarly wide, but smooth and somewhat bulbous or inflated; the form of the same surface in other batrachosauroidids is uncertain.

Compared to the two named batrachosauroidids in the Lance Formation ( Fig. 5 View Fig ), AMNH FARB 22965 more closely resembles dentaries of Opisthotriton kayi in being relatively elongate and shallow (vs. relatively shorter anteroposteriorly and deeper in Prodesmodon copei ), in bearing a ventrolabial ridge anteriorly (less prominent in O. kayi , see Estes 1964: fig. 39d, and unknown for Pro. copei ), in having its symphysial surface subtriangular in outline deepest anteriorly and narrowing ventroposteriorly in both vs. narrower and more rectangular in Pro. copei ), and teeth pedicellate or subpedicellate (vs. consistently nonpedicellate in Pro. copei ). By contrast, AMNH FARB 22965 more closely resembles dentaries of Pro. copei in having a similarly tall coronoid process (vs. relatively lower in O. kayi ). Compared to O. kayi and Pro. copei, AMNH FARB 22965 exhibits two intermediate conditions involving teeth. First, its tooth count is 17 (perhaps a few more if an additional tooth was present at the end of the tooth row and if the gap in the tooth row was infilled with teeth) vs. tooth counts of about 25 in O. kayi and 12–14 in Pro. copei . Second, the anteriormost six tooth pedicels in AMNH FARB 22965 are slightly recurved, similar to teeth along the entire tooth row in Pro. copei , yet the more posterior tooth pedicels in AMNH FARB 22965 are straighter, like those along the entire tooth row in O. kayi .

Based on the suite of features listed above, AMNH FARB 22965 is sufficiently unique that it almost certainly represents a new genus and species of batrachosauroidid. At this time, I defer formally naming that new taxon because only one incomplete dentary is available and certain of its features (i.e., bony lingual trough, apparent gap in the tooth row, no obvious Meckelian fossa or groove, and symphysial-like first tooth) are so peculiar that those likely are anomalies and, potentially, may have unduly compromised the structure of AMNH FARB 22965. Additional dentaries or complementary upper jaws are needed to corroborate the features described above for AMNH FARB 22965 and to confirm that it pertains to a new batrachosauroidid taxon.

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.

|

Kingdom |

|

|

Phylum |

|

|

Class |

|

|

SubClass |

Lissamphibia |

|

Order |

|

|

Family |