Myotis myotis

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/ 10.5281/zenodo.6397752 |

|

DOI |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6577990 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/4C3D87E8-FF2C-6A9C-FA8D-9DE9196CB989 |

|

treatment provided by |

Conny |

|

scientific name |

Myotis myotis |

| status |

|

487. View Plate 74: Vespertilionidae

Greater Myotis

French: Grand Murin / German: GroRes Mausohr / Spanish: Ratonero grande

Other common names: Greater Mouse-eared Bat, Large Mouse-eared Bat, Mouse-eared Bat, Mouse-eared Myotis

Taxonomy. Vespertilio myotis Borkhausen, 1797 View in CoL ,

Thuringia, Germany.

Subgenus Myotis ; myotis species group. See M. blythii . Taxonomic and phylogenetic relationships between M. blythii and M. myotis are still controversial and need additional research. They interbreed and produce viable hybrids. Two subspecies recognized.

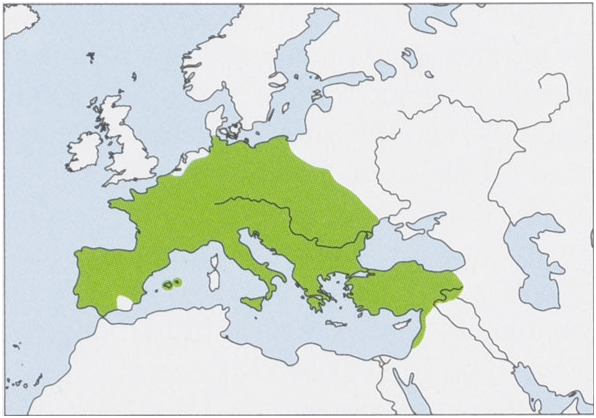

Subspecies and Distribution. M.m.myotisBorkhausen,1797—S&CentralEurope,fromPortugaltoTurkey,alsoinBalearicIsandSicily,withthelimitsofitsdistributioninNofGermany,SofDenmark,Netherlands,NofPolandandWUkraine.

M. m. macrocephalicus D. L. Harrison & Lewis, 1961 — E Mediterranean countries. View Figure

Descriptive notes. Head-body 65-84 mm, tail 40-60 mm, ear 24-4-27- 8 mm, forearm 55-66- 9 mm; weight 20-27 g. The Greater Myotis is one of the largest bat species in Europe and the largest species of Myotis , with females being slightly larger than males. Color differs quite remarkably between dorsum (reddish or brown) and venter (whitish or pale cream-beige). Fur is generally short and dense, with woolly aspect. Yellowish collar is sometimes noticeable surrounding neck. Young tend to be more grayish than adults, with shorter and denser fur. Skin is paler than other congeners. Length of ears and muzzle (broad and large) are quite distinctive traits to identify Greater Myotis from a distance. Wings are blackish or dark brown and quite broad, with wingspans of 350-450 mm. Uropatagium is markedly large, with large calcar that helps them glean prey from the ground. Although some studies suggest that the Lesser Myotis ( M. blythii ) and the Greater Myotis are morphologically different in terms of ear size (shorter in the former), tragus tip (black), and tooth row length (less than 9- 8 mm), both species are so similar that identifying them by only morphological traits is not entirely reliable. Skull is large with robust rostrum and low braincase compared to unrelated Myotis ; forehead region is moderately concave and sagittal crest is strongly developed. P? is about one-half height and crown area of P? or less and is within tooth row. Chromosomal complement has 2n = 44 and FNa = 50 ( Turkey) or 52 ( Germany).

Habitat. Various habitats from deciduous forests (mostly open forests or forest edges) to semi-open and open grasslands and pastures, agricultural land, and fruit and olive orchards from sea level up to elevations of ¢. 2000 m. Greater Myotis is usually linked to habitats with large clearings and little ground cover because they hunt insects on the ground and need space to maneuver. Although in lower numbers, they also have been recorded in high-elevation meadows, pastures, and harvested fields.

Food and Feeding. The Greater Myotis is gleaner, specialized in capturing large arthropods such as Coleoptera (ground-dwelling beetles, Carabidae ), Orthoptera , and Aracnida (especially in the Mediterranean area) on the ground. Therefore,it tends to fly very slowly and 30-70 cm from the surface to increase chances of detecting prey. Along with echolocation, it relies on smell and audible sound detection;it passively listens for noises produced by prey. After prey is detected,it lands just above it and captures it with its mouth. After it captures a insects from a surface,it either consumesit in flight (if the prey is small) or hangs from a nearby perch (if the prey is large). It uses aerial hawking to hunt some insects (e.g. chafers). It can easily switch hunting strategy and habitat depending on insect availability. In fact,it always selects its hunting sites depending on higher density of suitable prey and better accessibility of ground-dwelling prey. When the Lesser Myotis and the Greater Myotis forage sympatrically, diets are partitioned with bush crickets and carabid beetles as their main food items, respectively.

Breeding. Maternity colonies can have up to several thousands of individuals, usually in caves, mines, or other underground roosts. Maternity colonies mainly have adult females and their offspring and only a few males; apparently these males are not the most reproductively successful because females prefer to mate with males from outside the colony that wait in small clusters and colonies nearby. Maternity colonies are placed in sites with temperatures of 30-34°C and are formed at the end of March and last until August. Females give birth in May—June (April in some Mediterranean countries), and after 6-8 weeks, young are fully independent. Locations of maternity colonies are strongly influenced by climate and parasite abundance in caves, and they might change from year to year. Most females become sexually active during the first and second year of life. Maximum longevity is up to 22 years in the wild.

Activity patterns. The Greater Myotis is generally classified as strictly cave dwelling. Depending on the region,it also uses artificial roosts in buildings (e.g. loft spaces, churches, cellars, and empty cavities below roofs) and very occasionally trees or bat boxes. In the northern part ofits distribution, Greater Myotis tend to roost in human structures, but in the southern part, they are mostly found in underground roosts (e.g. caves or mines). They emerge from cavesafter other species such as Schreibers’s Long-fingered Bat ( Miniopterus schreibersii ) and definitely forage later than pipistrelles ( Pipistrellus ). Nightly activity is equally bimodal, with a peak 1-2 hoursafter sunset and another before dawn. Echolocation calls are very similar among all species of Myotis in Europe. Greater Myotis emit extremely modulated pulses of 120-170 kHz down to 26-29 kHz, with peak frequency usually ¢.35 kHz and durations ¢.6-10 milliseconds.

Movements, Home range and Social organization. The Greater Myotis is not clearly migratory, but movements up to 436 km have been reported. The Strait of Gibraltar seems to act as a geographical barrier. Movements of 50-100 km are typical between summer and winter roosts. Every night, individuals fly 5-26 km to reach hunting sites. In some regions, Greater Myotis have foraging areas of up to 1000 ha. It is assumed to be gregarious, with relatively large colonies, but there are reports of solitary males and young females roosting alone in tree holes, bat boxes, and fissures of bridges. In winter, they seem to congregate in small clusters in mines, caves, bunkers, and tunnels, usually at 5-15°C, rather warm compared with other winter roosts. From the end of the maternity period to hibernation, Greater Myotis from various locations often swarm in roosts (caves or buildings) commonly used by males. Swarming period peaks in September. Greater Myotis are commonly found with other cave-dwelling bat species such as Greater Horseshoe Bats (Rhinolophus ferrumequinum), Mediterranean Horseshoe Bats (R. euryale), Lesser Myotis , Geoffroy’s Myotis ( M. emarginatus ), and Schreibers’s Long-fingered Bat ( Miniopterus schreibersii ).

Status and Conservation. Classified as Least Concern on The IUCN Red List. The Greater Myotis was possibly extirpated in the British Isles in the 1990s. Its populations dramatically decreased a few decades ago, but they now seem to be stable. Nevertheless,it is considered widespread and common in most ofits distribution.

Bibliography. Arlettaz (1996a, 1999), Arlettaz, Perrin & Hausser (1997), Arlettaz, Ruedi & Hausser (1991), Arlettaz, Ruedi, Ibanez et al. (1997), Audet (1990), Bachanek & Postawa (2010), Berthier et al. (2006), Castella & Ruedi (2000), Castella, Ruedi & Excoffier (2001), Castella, Ruedi, Excoffier, Ibanez et al. (2000), Coroiu et al. (2016), Furman et al. (2014), Guttinger et al. (2001), Habersetzer & Vogler (1983), Jebb et al. (2017), Obrist et al. (2004), Pacifici et al. (2013), Petri et al. (1997), Roué & SFEPM (1997), Rudolph et al. (2009), Ruedi & Castella (2003), Russo, Jones & Arlettaz (2007), Simon et al. (2004), Spitzenberger (2002), Volleth & Heller (2012), Wojciechowski et al. (2007), Zahn (1999).

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.

|

Kingdom |

|

|

Phylum |

|

|

Class |

|

|

Order |

|

|

Family |

|

|

Genus |

Myotis myotis

| Don E. Wilson & Russell A. Mittermeier 2019 |

Vespertilio myotis

| Borkhausen 1797 |