Asynaptini Rübsaamen & Hedicke

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/10.11646/zootaxa.4604.2.3 |

|

publication LSID |

lsid:zoobank.org:pub:0BA07364-39ED-4349-98C5-27431A90CEAA |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/4C408780-8A40-FFE8-23A4-6A47FD2968F5 |

|

treatment provided by |

Plazi |

|

scientific name |

Asynaptini Rübsaamen & Hedicke |

| status |

|

Asynaptini Rübsaamen & Hedicke View in CoL

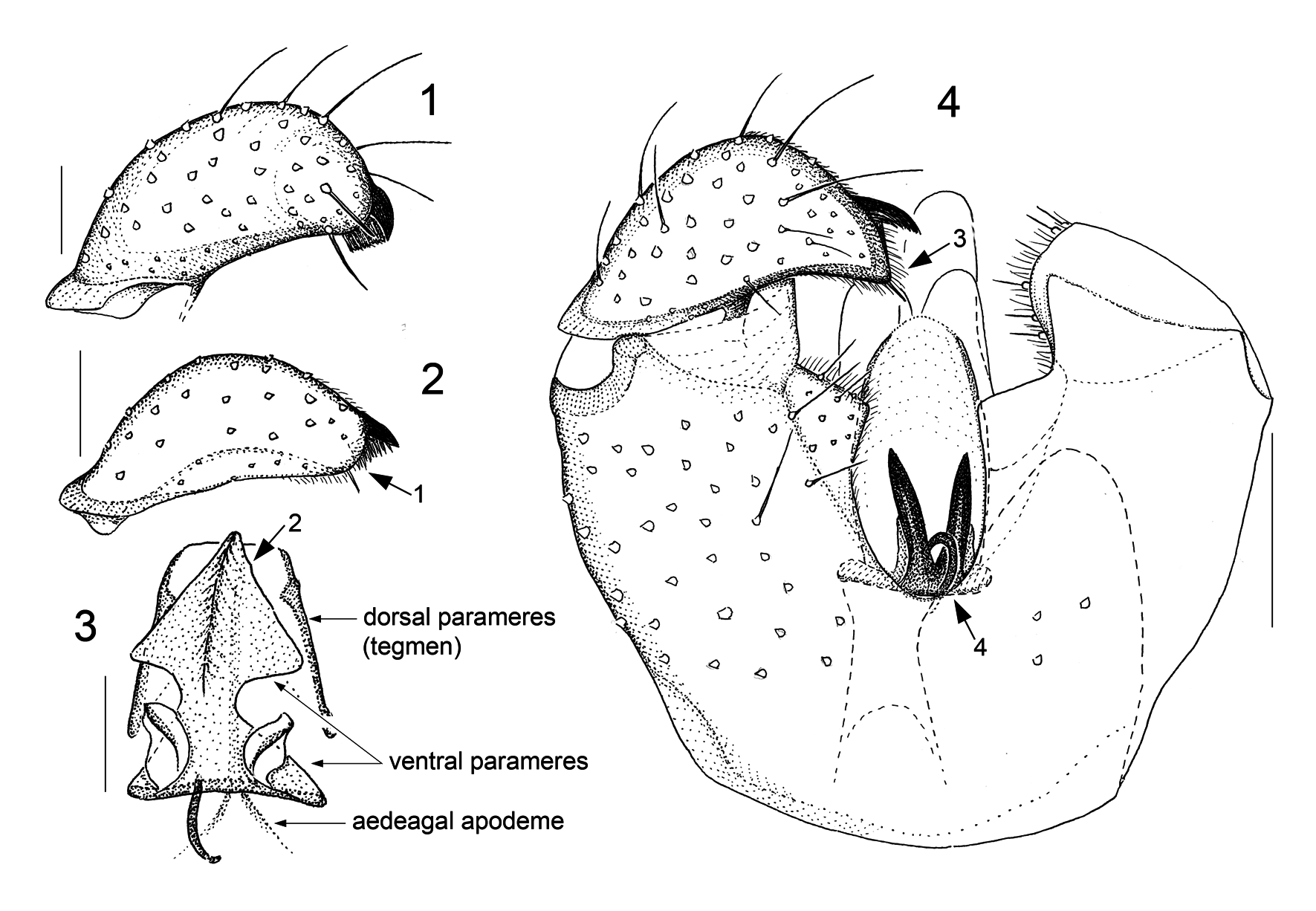

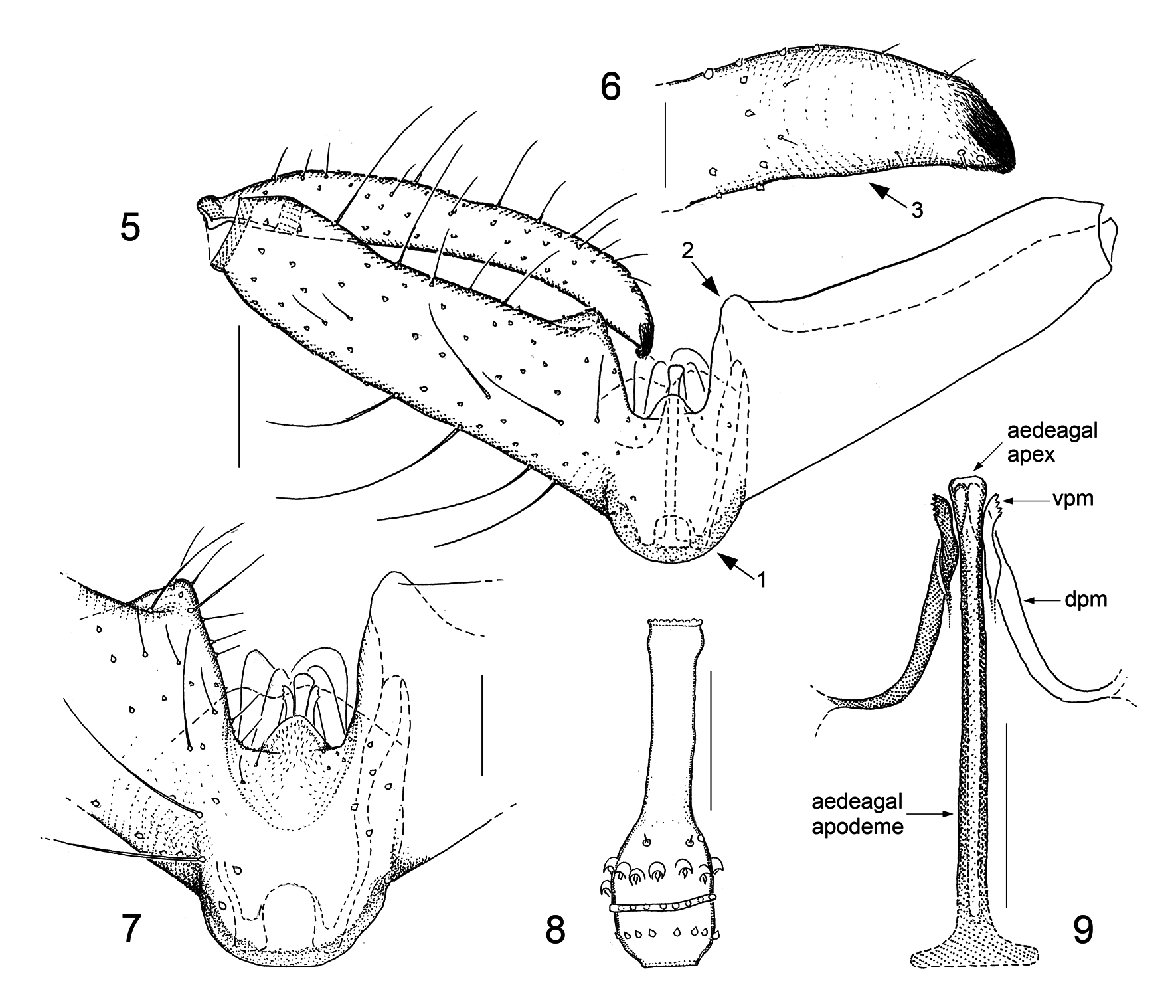

Adult Asynaptini View in CoL differ from other Porricondylinae View in CoL in that the maxillary protuberance (including stipes and cardo) is enlarged; the number of flagellomeres in both sexes usually exceeds 14 (up to 30 in males, 40 in females); male circumfila lack side branches; abdominal sclerites are subdivided into two or four portions; male gonocoxal processes are either rudimentary ( Asynapta View in CoL ) or absent (remaining genera); the central genitalic structures, i.e. parameres and aedeagus including ejaculatory apodeme, are closely interconnected to form a complex apparatus referred to as the copulatory organ; and the dorsal lamella of the ovipositor is reduced to only two segments, the basicercus and the disticercus ( Jaschhof & Jaschhof 2013). The construction of the copulatory organ is revisited here, prompted by some authors’ assigning to new genera Camptomyia View in CoL species with exceptionally odd parameres (see Fedotova & Sidorenko 2005; Fedotova 2018). A central point in our reinterpretation is the assumption of two pairs of parameres, ventral and dorsal, belonging to the basic pattern of asynaptine male genitalia. We further assume that the condition found in Parasynapta Panelius View in CoL comes closest to the ancestral pattern: two pairs of tusk-shaped parameres bordering the aedeagus whose anterior component is a simple, sclerotized rod (ejaculatory apodeme) and whose posterior component is a more complex, largely membranous extension (aedeagal head) ( Jaschhof & Jaschhof 2013: fig. 178C). The area where the ejaculatory apodeme transitions into the aedeagal head is normally somewhat thickened, marking the site where the pair of ejaculatory gland ducts enter the genital tube. The ends and orifices of those ducts are often slightly reinforced, which makes them better visible, particularly in Camptomyia View in CoL ( Jaschhof & Jaschhof 2013: fig. 174C). Examining extant Asynaptini View in CoL in their entirety, it is evident that parameres occur in a wide range of different shapes and varying degrees of connectivity with the aedeagus. The variation found in parameral structure includes the absence of one of the pairs or that both sides of a pair may be entirely or partly merged with each other to form a shield (tegmen). While the construction of the copulatory organ, including the parameres, differs from species to species, the basic design within a genus is to some extent distinctive; those genus-specific patterns are described here in more detail under Asynapta View in CoL and Camptomyia View in CoL . In this paper we employ terms for parts of the copulatory organ that differ from previous usage ( Jaschhof & Jaschhof 2013), as follows: ventral parameres (instead of parameres in Asynapta View in CoL , and parameral processes in Camptomyia View in CoL ), dorsal parameres (instead of aedeagal head in Asynapta View in CoL , and parameres in Camptomyia View in CoL ), aedeagal apodeme (instead of ejaculatory apodeme), and aedeagal apex (instead of aedeagal head) (see Figs 3 View FIGURES 1–4 and 9 View FIGURES 5–9 ).

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.

|

Kingdom |

|

|

Phylum |

|

|

Class |

|

|

Order |

|

|

Family |

|

|

SubFamily |

Porricondylinae |

Asynaptini Rübsaamen & Hedicke

| Jaschhof, Mathias & Jaschhof, Catrin 2019 |

Parasynapta

| Panelius 1965 |

Camptomyia

| Kieffer 1894 |

Camptomyia

| Kieffer 1894 |

Camptomyia

| Kieffer 1894 |

Camptomyia

| Kieffer 1894 |

Camptomyia

| Kieffer 1894 |

Asynapta

| Loew 1850 |

Asynapta

| Loew 1850 |

Asynapta

| Loew 1850 |

Asynapta

| Loew 1850 |