Dunkleosteus raveri, Carr & Hlavin, 2010

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/ 10.1111/j.1096-3642.2009.00578.x |

|

DOI |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.10545515 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/5415C76B-FF90-FFAB-9BEE-D5A0FDCD51CF |

|

treatment provided by |

Valdenar |

|

scientific name |

Dunkleosteus raveri |

| status |

sp. nov. |

DUNKLEOSTEUS RAVERI SP. NOV. ( FIGS 3–5 View Figure 3 View Figure 4 View Figure 5 )

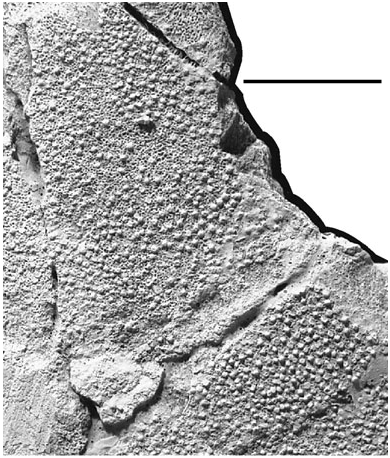

Diagnosis: A Dunkleosteus species possessing transverse articular facets on the prehypophysial region of the parasphenoid, retention of fine punctate tubercles for dermal plate ornamentation, and an anterior position of the anterior triple point (PrO/PtO/C plate junction) over the orbit.

Holotype: MCZ 13277 ( Figs 3–5 View Figure 3 View Figure 4 View Figure 5 ), an incomplete, uncrushed skull roof lacking the nuchal and left paranuchal plates, and much of the right paranuchal plate, and possessing an associated parasphenoid bone (in ventral view). The holotype represents the only recognized available material.

Etymology: Named after the collector, Clarence Raver of Wakeman, Ohio.

Occurrence and stratigraphy: Recovered from a shale pit south-west of the intersection of Route 2 and Rye Beach Road, and between Sawmill Creek and Rye Beach Road, Huron Township, Erie County, Ohio ( Fig. 2A View Figure 2 ). The shale pit has subsequently been covered by commercial development; however, laterally equivalent sediments are exposed in Sawmill Creek. Collected from the basal 1.5–3 m of the Huron Shale Member ( Fig. 2B View Figure 2 ), Ohio Shale Formation (Famennian, Over & Rhodes, 2000), which rests upon on the Middle Devonian Prout Limestone ( Hoover, 1960). Found within a large carbonate concretion typical of the Huron Shale. Dunkleosteus raveri sp. nov. is further distinguished from the only other Dunkleosteus species within the Ohio Shale Formation ( Du. terrelli ) by its lower and non-overlapping stratigraphic position.

SKULL ROOF AND PARASPHENOID

The skull roof ( Fig. 3 View Figure 3 ), in terms of individual plate shape and sensory line pattern, is comparable with that of Du. terrelli ; however, it is preserved only incompletely, with portions of ten dermal plates present (parts of five paired and three median plates). The internasal, postnasal, postmarginal, gnathals, and cheek plates are not preserved. The plates are covered by a fine punctate tuberculation. The sensory line grooves follow a typical arthrodiran pattern ( Heintz, 1932, figs 42, 43). Internally, the skull roof is reinforced by lateral thickening (an occipital thickening is not preserved, with only a small portion of the nuchal thickening remaining, th.n; Fig. 4A View Figure 4 ).

The preparation of the external surface is incomplete in some areas, and in other areas the removal of matrix has resulted in the loss of the most superficial layers. Additionally, many fractures are present as a result of the expansion of calcitic matrix during concretion growth. These diagenetic and preparatory features result in a loss of information concerning the visibility of plate boundaries. The contact surfaces between adjacent plates are denoted as either a contact face on the visceral surface or an overlap area on the external surface (after Dennis & Miles, 1979a).

The rostral plate (R; Fig. 3A View Figure 3 ) is T-shaped, with the anterolateral region overlapping the preorbital plate. A posterior fragment of the rostral plate overlies the pineal plate, suggesting that the rostral plate overlapped the pineal plate, although a distinct overlap area is not clear on the latter plate. Internally, an anterior thickening is not discernible (see also Carr, 1991, a.th, fig. 4A).

The pineal plate (P; Fig. 3A View Figure 3 ) is narrow, being over three times longer than wide (length/width of exposed plate is ~3.3). The pineal plate is overlapped by the adjacent rostral, preorbital, and central plates, thereby separating the preorbital plates posteriorly. Internally, a pronounced ridge (r; Fig. 4A View Figure 4 ) posteriorly bounds the internal pineal fossa.

The preorbital plate (PrO; Fig. 3A, B View Figure 3 ) is crossed by a supraorbital sensory line groove (soc; Fig. 3A View Figure 3 ). The orbit is bounded anteriorly by a pronounced dermal preorbital process (d.prp; Figs 3B View Figure 3 , 4A View Figure 4 ). Internally, thickenings of the dermal preorbital process form the anterior border of the supraorbital vault (suo.v; Fig. 4A View Figure 4 ). Mesially, a channel for the neurocranial preorbital process (ch.pro.pr; Fig. 4A View Figure 4 ) is bounded laterally by the steep face of the supraorbital vault, and anteriorly by the supraethmoid crista (cr.seth; Fig. 4A View Figure 4 ). This crista extends only to the edge of the rostral plate. Along the anterolateral part of the dermal preorbital process are contact faces for the suborbital and postnasal plates (cf.SO and cf.PN, respectively; Fig. 4A View Figure 4 ; ss, pns of Heintz, 1932, fig. 13).

The postorbital plate (PtO; Fig. 3A, B View Figure 3 ) is traversed by three sensory line grooves: the central, postorbital and otic branches of the infraorbital sensory line (csc, ioc.pt, ioc.ot, respectively; Fig. 3A, B View Figure 3 ). Branches of the infraorbital line meet at an angle of ~95°. A dermal postorbital process (pto.pro; Figs 3B View Figure 3 , 4A View Figure 4 , associated with the postorbital branch of the infraorbital line groove) forms the posterior boundary of the orbit. Internally, the supraorbital vault is continued, and is bounded posteriorly by the posterior supraorbital crista (cr.pso; Fig. 4A View Figure 4 ). The supraorbital vault is deeper in its posteromedial corner, where there is a distinct dermal ventral postocular process (pt.o.pr; Figs 3B View Figure 3 , 4A View Figure 4 ; or the neurocranial process of Heintz, 1932; contra the presence of a simple thickening, as seen in Harrytoombsia elegans Miles & Dennis, 1979 , and the Camuropiscidae Dennis & Miles, 1979a ; character 4, Appendix 2). Posterior to this dermal ventral postocular process, the lateral consolidated arch continues as the inframarginal crista (cr.inf; Fig. 4A View Figure 4 ). A shallow anterior depression in the crista denotes the location of the anterior postorbital neurocranial process ( Goujet, 1984: pr.poa, figs 6, 10).

The central plate (C; Fig. 3A, B View Figure 3 ) outline is difficult to discern. Anteriorly, the outline of the plate is transverse, with the preorbital plate forming a shallow embayment. Laterally, the postorbital plate forms an embayment, although it appears to be shallow on the left and more deeply notched on the right. Anteriorly, the central plates are separated by the pineal plate for ~40% of their midline length. The posterior margin is incomplete. The supraorbital and central sensory line grooves cross the central plate, with both grooves ending at the level of the ossification centre. A contact between the central and the marginal plates is visible, although the total length of the contact is not clear. Internally, the pre-endolymphatic thickening (th.pre; Fig. 4A View Figure 4 ) extends from the lateral consolidated arch to the nuchal thickening (th.n; Fig. 4A View Figure 4 ), and shows a central depression. The preendolymphatic thickening forms a distinct anteromedial boundary for the parabranchial chamber (f.pb; Fig. 4A View Figure 4 ; cucullaris depression of Stensiö, 1963; refer to Carr, Johanson & Ritchie, 2009, for a discussion of the terminology applied to this region). A radiating pattern is present on the internal thin portion of the central plate (the ‘ossification rays’ of Heintz, 1932: 135).

The marginal plate (M; Fig. 3A, B View Figure 3 ) contacts the central plate. The otic branch of the infraorbital sensory line groove continues until the ossification centre of the marginal plate. The main sensory line groove (lc; Fig. 3A, B View Figure 3 ) continues onto the paranuchal plate. A postmarginal sensory line groove (pmc; Fig. 3A, B View Figure 3 ) is present and ends before the edge of the plate. Internally, a pronounced inframarginal crista continues to the edge of the plate, and apparently onto the postmarginal plate (cr.inf; Fig. 4A View Figure 4 ).

The postmarginal plate, which is not preserved, should form the posterolateral corner of the skull roof. The arrangement of the marginal and paranuchal plates suggests that the marginal plate would form the larger overlap for these two plates on the postmarginal plate.

The paranuchal plate (PNu; Fig. 3A, B View Figure 3 ), incomplete, is crossed by the continuation of the main lateral line groove. The marginal plate seems to form an embayment of the paranuchal plate in the area of the main lateral line, thereby forming a broad posterolateral process that overlaps the postmarginal plate. A descending face along this process forms part of the subobstantic area (soa; Fig. 3B View Figure 3 ; see also Dennis- Bryan, 1987: soa, fig. 5). The transverse occipital thickening and articulations with the thoracic armour are not preserved.

The parasphenoid (Psp; Fig. 4 View Figure 4 ) is exposed in ventral view and is displaced. Distinct anterior superognathal articular surfaces (art.ASG; Fig. 4B View Figure 4 ) are visible on the transverse anterior margin of the parasphenoid. These surfaces form shallow depressions separated medially by small dorsal and ventral processes, and an intervening ridge. The orientation and shape of the articular surfaces are comparable with the condition observed in Du. terrelli . The paired buccohypophysial foramen (f.bhy; Fig. 4B View Figure 4 ) is visible in ventral view, with the prehypophysial region (pre.reg; Fig. 4B View Figure 4 ) being longer than the posthypophysial region (post.reg; Fig. 4B View Figure 4 ; ~1.5 times longer in an anterior–posterior direction). Both the pre- and posthypophysial regions are wider than long.

The ornamentation of the skull roof consists of a fine, evenly spaced ornament of punctate tubercles ( Fig. 5 View Figure 5 ). D. Goujet (pers. comm.) suggests caution in using the presence or absence of ornamentation as a phylogenetic character. This is based on the presence of both ornamented and unornamented forms of Plourdosteus trautscholdii ( Eastman, 1897) within the same locality. However, a review of all of the specimens of Dunkleosteus from the Cleveland Shale Formation curated at the Cleveland Museum of Natural History supports the presence of distinct stratigraphic distributions of ornamented and unornamented Dunkleosteus species.

| MCZ |

Museum of Comparative Zoology |

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.