Saimiri boliviensis (I. Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire & de Blainville, 1834)

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6628559 |

|

DOI |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6628584 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/560F8786-B720-2851-0DFB-F5D03AFEF23F |

|

treatment provided by |

Jonas |

|

scientific name |

Saimiri boliviensis |

| status |

|

Black-capped Squirrel Monkey

Saimiri boliviensis View in CoL

French: Saimiri de Bolivie / German: Schwarzkappen-Totenkopfaffe / Spanish: Mono ardilla boliviano

Other common names: Bolivian Squirrel Monkey (boliviensis), Peruvian Squirrel Monkey ( peruviensis)

Taxonomy. Callithrix boliviensis 1. Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire & de Blainville, 1834,

Guarayos Mission, Rio San Miguel, Santa Cruz, Bolivia.

In a review of the taxonomy of the uacaris published in 1987, P. Hershkovitz recognized S. b. jaburuensis and S. b. pluvialis as valid subspecies. They were listed by C. P. Groves in 2001 as synonyms of the nominate subspecies boliviensis . This species may hybridize with S. ustus where the two are sympatric. S. boliviensis is chromosomally distinct, with five pairs of acrocentric chromosomes. Natural hybrids of S. b. peruviensis x S. macrodon have been recorded from Pucallpa, Peru, and the Rio Ucayali (Tapiche Basin). Two subspecies recognized.

Subspecies and Distribution.

S. b. boliviensis 1. Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire & de Blainville, 1834 — upper Brazilian Amazon S of the Rio Solimoes, from between the rios Jurua and Tefé extending S into SE Peru (S of Rio Abujao, Ucayali Department) and N Bolivia W of the Rio Guaporé (Beni, Cochabamba, Pando, and Santa Cruz departments, including the upper Madeira Basin), at elevations of 50-500 m.

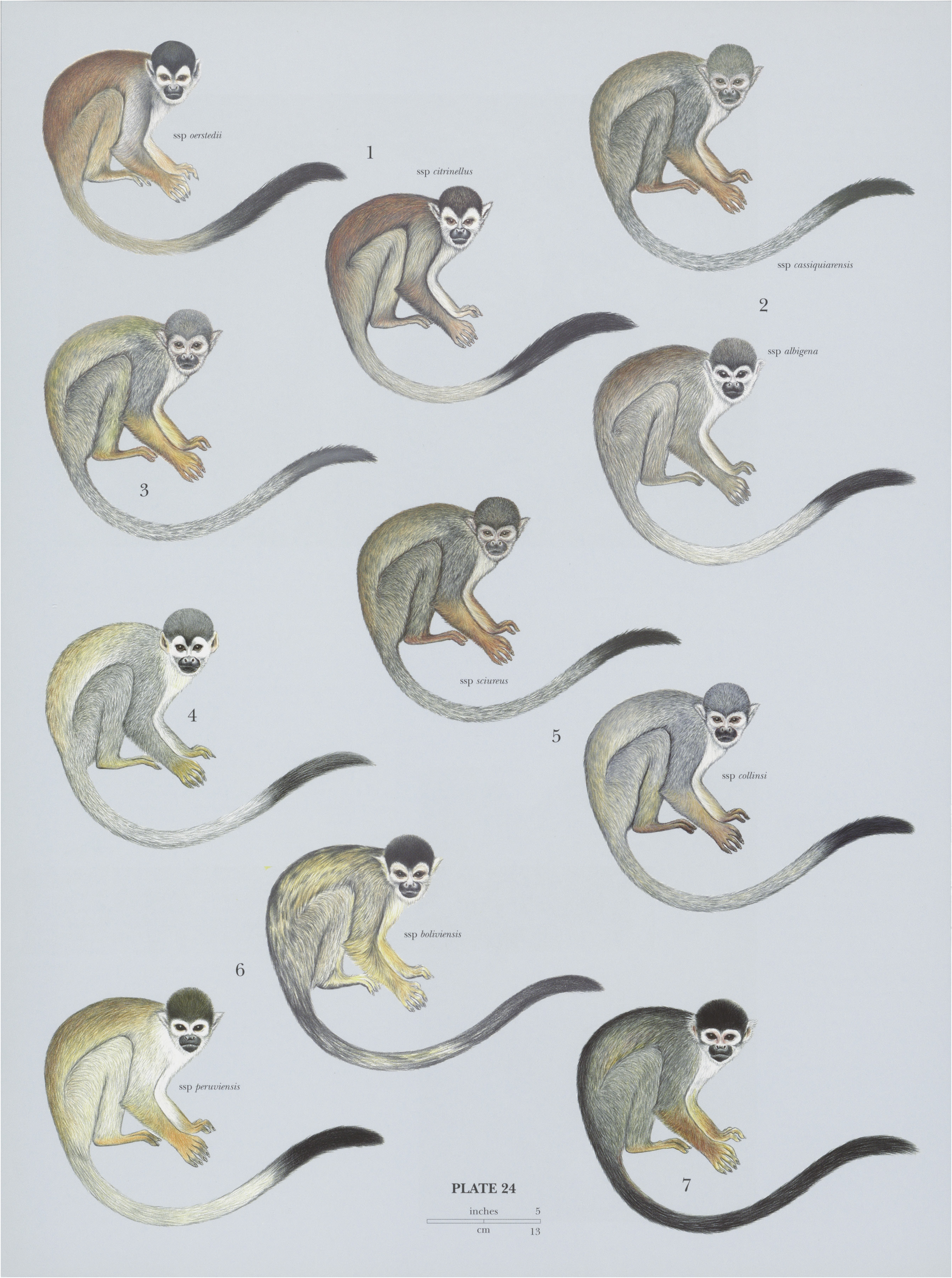

S. b. peruviensis Hershkovitz, 1984 — N & C Peru, S of the Rio Maranon-Amazonas, from the W bank of the Rio Tapiche W to the Rio Huallaga, and S through the departments of San Martin and of Huanuco (to c.10° S), and Ucayali (between the rios Pachitea and Tambo, at least as far as the Rio Abujao); also possibly in Brazil (Amazonas State), at elevations of 90-800 m. View Figure

Descriptive notes. Head-body 28-31.5 cm (males) and 26.5-28.5 cm (females), tail 38-43 cm (males) and 39-5—-41 cm (females); weight c.1 kg (males, varies by season) and 700-900 g (females) for the “Bolivian Squirrel Monkey” (S. b. boliviensis ). Head-body 27.3-32 cm (males) and 26:5-27.7 cm (females), tail 37.4-43.5 cm (males) and 37.7-40.4 cm (females) for the “Peruvian Squirrel Monkey” (S. b. peruviensis). The Black-capped Squirrel Monkey is sexually dichromatic. Males tend to be gray and females blackish, although normally both have a blackish crown and golden-yellow forearms, hands, and feet. There are narrow white lines of fur on each brow of the “Roman arch” type. The tail pencil is black and thin. The principal distinguishing character of the Bolivian Squirrel Monkey is the entirely agouti pelage of the forehead. The crown and preauricular patch are blackish in both sexes. The tail is grayish or buffy-agouti to blackish above, with a black tip. In the Peruvian Squirrel Monkey, the crown and preauricular patch are agouti in males and mainly black or blackish-agouti in females. The tail is grayish to blackish-agouti above, with a black tip.

Habitat. All types of humid forest in the western Amazon, from river edge and seasonally flooded forests to terra firma forest. Black-capped Squirrel Monkeys tend to use terra firma forest only seasonally, depending on fruit abundance and dispersion. Their preferenceis for river edge, lacustrine succession, and flooded forests. Although Black-capped Squirrel Monkeys often feed on fruits in large-canopied, tall trees (especially Ficus and Brosimum , both Moraceae ) in the upper canopy and even emergent vegetation, they travel mainly in the middle canopy and understory, 10-15 m above the ground.

Food and Feeding. Diet of the Black-capped Squirrel Monkey is largely small animal prey and fruit. Its feeding ecology was studied by J. Terborgh and colleagues at Cocha Cashu in Manu National Park and Biosphere Reserve, Peru. Fruits they eat are generally small (mostly 1 cm or less in diameter or the short axis), succulent, and sweet, including berries and drupes that are often yellow or orange when ripe. The diet includes fruits from more than 150 species in 42 families. In the wet season, various fruits comprise 100% of the plant part of their diet. In the dry season, when fruit production in the forest is generally low, Black-capped Squirrel Monkeys are able to maintain a high a percentage of fruit (91%) in their diet by concentrating on figs; there are 16 species of Ficus (Moraceae) at Cocha Cashu, 13 of them providing fruits for squirrel monkeys. The three most important species are FE perforata, FE killipii, and FE erythrosticta. In May during the early dry season, for example, Blackcapped Squirrel Monkeys spent 90% oftheir fruit feeding time on figs, which equaled 77% of their time spent feeding overall. In the dry season, they also lick nectar from flowers of Combretum assimile ( Combretaceae ) and Quararibea cordata ( Bombacaceae ). Large-canopied figs produce enormous quantities of small fruits, attracting a wide range of birds and mammals for periods of c.10 days. Tall trees (up to 30-40 m) are sparsely distributed through the forest, and Black-capped Squirrel Monkeys,like the sympatric Shock-headed Capuchins ( Cebus cuscinus ) that also depend on figs in the dry season, range widely (450 ha). Because of their heavy use of figs, in which the entire group can feed simultaneously, Black-capped Squirrel Monkeys spend ¢.50% of their feeding time in the canopy or emergent vegetation at heights of 30 m or more. Black-capped Squirrel Monkeys at Manu and Central American Squirrel Monkeys (S. oerstedii ) differ in their use of the small-canopied trees they exploit for fruits. Central American Squirrel Monkeys exploit species that produce fruits in small quantities over long periods. Black-capped Squirrel Monkeys at Manu eat a much larger diversity of fruits, which typically produce large crops that ripen over a short period or even simultaneously, in both largeand small-canopied trees. As a result,sizes of feeding parties differ: typically, 3-4 Central American Squirrel Monkeys and 17-18 Black-capped Squirrel Monkeys. As for all squirrel monkeys, Black-capped Squirrel Monkeys are efficient, rapid foliage gleaners; 83% of their foraging time is spent scanning and manipulating leaves of trees and vines for exposed rather than hidden prey. About one-half of all prey they take is immobile or sluggish that they grab from leaves, and c.30% are mobile insects that they snatch, even in mid-air, or pounce on. Orthopterans comprise ¢.33% of their prey, and c.50% are lepidopteran larvae, pupae, and adults. They also eat hymenopteran larva, galls, beetles, snails, frogs, lizards, nestlings, and numerous other small items that are impossible to identify. Black-capped Squirrel Monkeys are the most intense and rapid foragers, catching prey at a faster rate than any of the primates at Cocha Cashu. They capture prey at twice the rate of sympatric capuchin species, nearly one item per minute. When insects are scarce, particularly toward the end of the dry season, they increase their search rate and are thus able to maintain capture rates of 53-64 captures/hour during the year. Most of their foraging for animal prey is done while moving slowly through the understory and lower canopy at heights of 5-10 m.

Breeding. As many as 23 breeding females can occurin a single group of Black-capped Squirrel Monkeys. Females give birth for the first time at c.2-5 years of age. Males reach reproductive maturity at about six years. As in other species of Saimiri , male Black-capped Squirrel Monkeys become “fatted” prior to the mating season, which lasts about two months. Births occur also during a two-month period, in contrast to the tight synchrony of two weeks in the Central American Squirrel Monkey and less than one week in the Guianan Squirrel Monkey (S. sciureus ). Females other than the mother care for infants and may suckle them. Interbirth interval is 24 months, double those of Guianan and Central American squirrel monkeys.

Activity patterns. Black-capped Squirrel Monkeys spend most of their day traveling through the understory searching for animal prey, finding occasional fruits from relatively small-canopied understory trees (5 m or less in diameter), and making short but frantic excursions up into the canopy to raid the large fruits of fig trees. At these times, the entire group may feed on fruits together. About 11% of the day is spent feeding on fruit or nectar, and another 11% resting. About 43% of theirfruit feeding time is spent in large trees with canopies of 20 m or more.

Movements, Home range and Social organization. Group sizes of Black-capped Squirrel Monkey at Manu National Park and Biosphere Reserve are 35-65 individuals, and home ranges are 250-500 ha. Home ranges of different groups overlap, and there is no evident territorial behavior. Groups have been seen feeding on fruits in a large fig tree one after the other or even at the same time in neighboring Brosimum trees. There is, however, competition for food within groups. Food-based disputes are 70 times more frequent in groups of Black-capped Squirrel Monkeys (although still not very frequent) than they are in egalitarian and peaceful groups of the Central American Squirrel Monkeys where such aggressive interactions occur 0-3 times/hour. Only twelve aggressive interactions (all disputes over animal prey) were recorded in more than 3000 observations of Central American Squirrel Monkeys. In ¢.23% of encounters (95% disputing fruit in fruiting trees), Black-capped Squirrel Monkey females interacted in coalitions; female Central American Squirrel Monkeys do not form coalitions . Female Black-capped Squirrel Monkeys stay in their natal group and, as adults, establish dominance hierarchies and develop alliances in kin-based coalitions. Male-male aggression is also common, and males also form coalitions . Males play no particular role in group vigilance and do not defend group members from predators. They disperse from their natal groups at 4-5 years of age and form allmale groups before attempting to join a mixed-sex group. Male coalitions are known to transfer between groups every 2-3 years. Females are dominant to males and keep them on the periphery of the group except during the mating season. Black-capped Squirrel Monkeys regularly travel with Large-headed Capuchins ( Sapajus macrocephalus ). The capuchin monkeys are usually the leaders, and it is believed that they help squirrel monkeys locate large crops of fruits such as figs. In a two-month study at Cocha Cashu, a group of 40-50 Black-capped Squirrel Monkeys associated with capuchin groups for ¢.63% of their time, with distances of 50 m or less between groups. Capuchin groups are smaller (8-12 individuals) and have smaller home ranges (c.80 ha), so squirrel monkeys with larger home ranges associate with up to five different capuchin groups. Association with any particular capuchin group generally lasts about five days, but sometimes they travel together for up to twelve days. When in association with capuchins, squirrel monkeys eat more fruit and nectar and spend less time foraging for animal prey. Capuchins are larger but are outnumbered by the squirrel monkeys. Squirrel monkeys benefit from being led to large fruit crops, which capuchin monkeys are unable to monopolize, but there is a cost. Capuchins are able to monopolize medium-sized and smaller crops, which they locate with the help of the squirrel monkeys. Capuchins travel higher in the forest using more vines and palms where they forage for insects. Foliage gleaning squirrel monkeys, on the other hand, travel and forage more through small and medium-sized trees where they are more likely to discover small to middle-sized fruit crops, which can then be taken over by capuchins. Competition means that both capuchins and squirrel monkeys eat faster when they are traveling together. Capuchins can also dominate insect infestations, such as caterpillar swarms, to the detriment of squirrel monkeys. On the plus side, squirrel monkeys occasionally benefit by gaining access to otherwise inaccessible mesocarp of discarded and dropped Scheelea palm fruits during and following feeding bouts by capuchins. The ornate hawk-eagle (Spizaetus ornatus) and the Ocelot (Leopardus pardalis) are confirmed predators of Black-capped Squirrel Monkeys, and the harpy eagle (Harpia harpyja) and the black-and-white hawk-eagle (Spizaetus melanoleucus) have also been seen to attack them. C. Peres compared densities in terra firma and seasonally flooded (varzea) forests along the Rio Jurua. At two varzea sites in the Brazilian Amazon, he obtained densities of 70-7 ind/km? (Sacado do Condor) and 149-2 ind/km?® (Boa Esperanca), and at six terra firma forest sites, also in the Brazilian Amazon, densities were considerably lower: 11-3 ind/km?* (Porongaba), 36-4 ind/km? (Kaxinawa reserve), 25-4 ind/km?* (Penedo), 28-7 ind/km?® (Altamira), 7-7 ind/km? (Igarapé do Jaraqui), and 13-5 ind/km?* (Vai Quem Quer). Density in Manu National Park and Biosphere Reserve, Peru was 50 ind/km*in a forest of lacustrine succession (around Cocha Cashu).

Status and Conservation. CITES Appendix II. Classified as Least Concern on The [UCN Red List, including both subspecies. The Bolivian Squirrel Monkey occurs in Amboro, Isiboro Securé, Carrasco, and Madidi national parks, Manuripi-Heath and Rios Blanco y Negro national reserves, and Beni and Pilon Lajas biosphere reserves in Bolivia; and Serra do Divisor National Park, Rio Acre Ecological Station, and possibly Abufari Biological Reserve in Brazil. In Peru,it occurs in Manu National Park and Biosphere Reserve, Yanachaga-Chemillén National Park, and possibly Bahuaja-Sonene National Park and Tambopata National Reserve. The Peruvian Squirrel Monkey occurs in Pacaya-Samiria National Reserve in Peru.

Bibliography. Aquino & Encarnacion (1994b), Boinski (1999a, 1999b), Groves (2001), Hershkovitz (1984, 1987¢), Jones et al. (1973), Martinez et al. (2010), Mendoza, Lowe & Levine (1978), Mitchell, C.L. (1991, 1994), Mitchell, C.L. et al. (1991), Schneider, Harada et al. (1993), Silva, Sampaio, Schneider, Schneider, Montoya, Encarnacion, Callegari-Jacques & Salzano (1993), Silva, Sampaio, Schneider, Schneider, Montoya, Encarnacion & Salzano (1992), Terborgh (1983, 1985), Williams, Gibson et al. (1994), Williams, Vitulli et al. (1986).

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.

|

Kingdom |

|

|

Phylum |

|

|

Class |

|

|

Order |

|

|

Family |

|

|

Genus |

Saimiri boliviensis

| Russell A. Mittermeier, Anthony B. Rylands & Don E. Wilson 2013 |

Callithrix boliviensis 1. Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire & de Blainville, 1834,

| Geoffroy Saint-Hillaire & de Blainville 1834 |