Saimiri oerstedia (Reinhardt, 1872)

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6628559 |

|

DOI |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6628231 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/560F8786-B727-2854-0800-FE663A75F444 |

|

treatment provided by |

Jonas |

|

scientific name |

Saimiri oerstedia |

| status |

|

Central American Squirrel Monkey

French: Saimiri a dos roux / German: Mittelamerika-Totenkopfaffe / Spanish: Mono ardilla de América Central

Other common names: Red-backed Squirrel Monkey; Black-crowned Central American Squirrel Monkey (oerstedii), Gray-crowned Central American Squirrel Monkey ( citrinellus)

Taxonomy. Chrysothrix oerstedti Reinhardt, 1872 ,

vicinity of David, Chiriqui, Panama.

S. oerstedui has five pairs of acrocentric chromosomes. Two subspecies recognized.

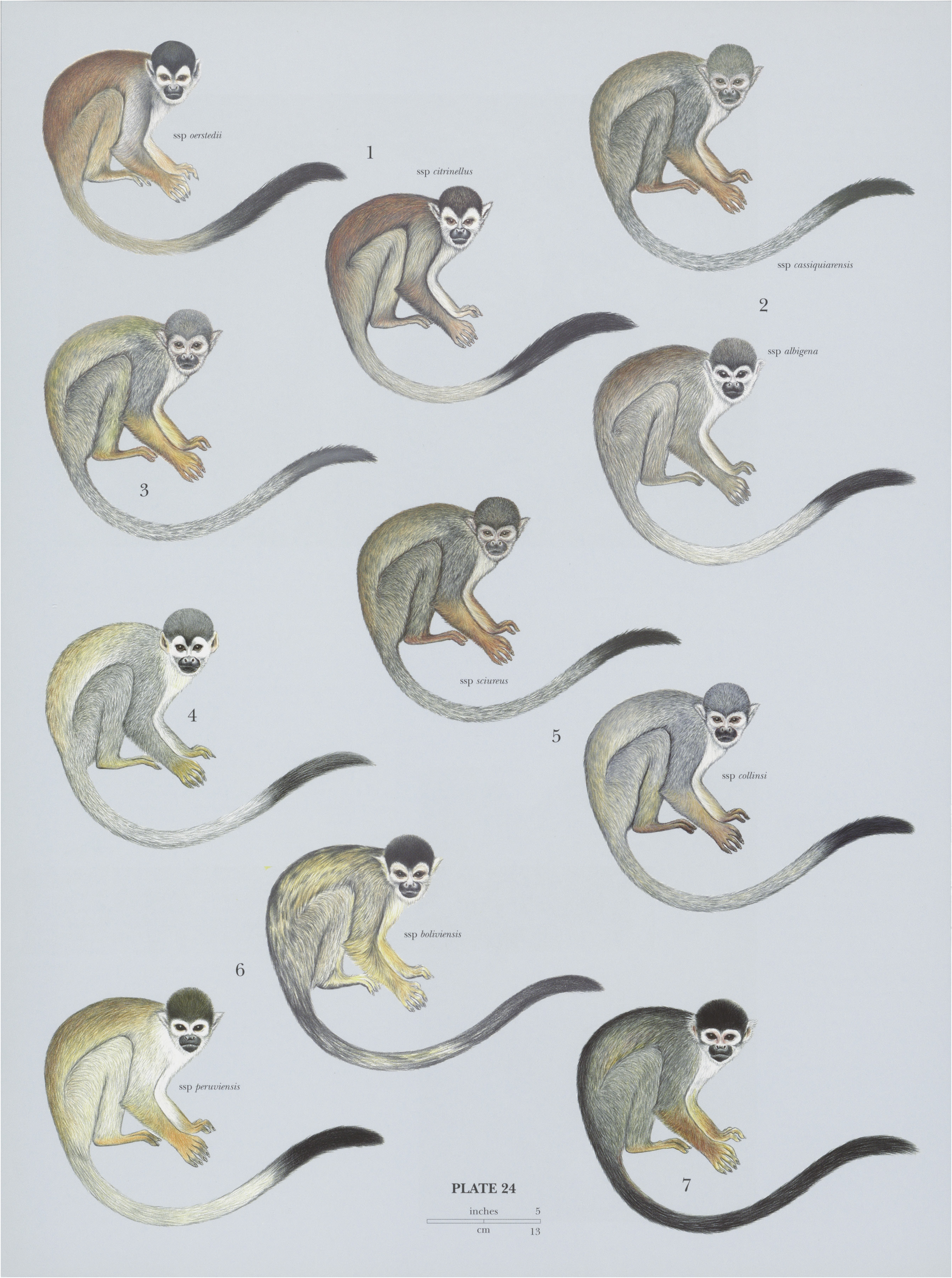

Subspecies and Distribution.

S. o. citrinellus Thomas, 1904 — historically along the Pacific coast of W Costa Rica in Puntarenas Province (elevations up to 500 m), the NE limit marked by the Rio Tulin in the N Herradura Mts (9° 40’ N, 84° 35° W) and Dota Mts (9° 37’ N, 84° 35° W), and the S limit by the N bank of the Rio Grande de Térraba (8° 25’ N, 84° 25’ W); its populations are entirely fragmented. View Figure

Descriptive notes. Head-body 28-33 cm,tail 33-43 cm; weight 750-950 g (males) and 600-800 g (females). Female Central American Squirrel Monkeys tend to be c.16% smaller than males. The crown is dark, with tufted ears. White arches above the eyes are of the “Gothic” type. The back and sides of the trunk are largely bright orange or reddish orange. In the “Black-crowned Central American Squirrel Monkey” (S. o. oerstedir), crowns of males and females are black, and outersides of legs are orange like arms. In the “Gray-crowned Central American Squirrel Monkey” (S. o. citrinellus), crowns of males are agouti and are black in females. Males have no sideburns, and their preauricular patch is agouti or buffy, like their cheeks. Females have dark sideburns separating the white face patch from the white fur of the ear. Outersides of legs are buffy or grayish-agouti.

Habitat. Lowland evergreen forest, with a preference for middle and lower canopies of secondary forest. Central American Squirrel Monkeys enter tall mature forest and late successional forest at times of food scarcity (late wet season). In Corcovado National Park, Costa Rica, where the Central American Squirrel Monkey has been studied by S. Boinski and her students and colleagues, it prefers forest with a heavy herbaceous ground cover of Musa sapientum ( Musaceae ), Heliconia (Heliconiaceae) , and Piper (Piperaceae) ; a shrubby understory; and early pioneer trees that sometimes form dense stands, such as Cecropia obtusifolia ( Urticaceae ), Posoqueria latifolia ( Rubiaceae ), Vitex cooperi ( Verbenaceae ), and Psidium guajava ( Myrtaceae ). In more advanced stages of succession, abundant trees include Ficus (Moraceae) , Inga (Fabaceae) , Apeiba membranacea ( Tiliaceae ), Spondias mombin ( Anacardiaceae ), and Quararibea asterolepis ( Malvaceae ). Forests of the Pacific coasts of Costa Rica and Panama receive heavy annual rainfall, averaging 4970 mm. Some years are very wet, others drier, and there are marked seasons—Ilate wet season, dry season, early wet season, and mid-wet season— when food availability clearly differs. Fewer insects are available during the midand late periods of the wet season (torrential rains and little fresh foliage) compared with the dry season and early wet season. Fruits and flowers are least abundant in the late wet season and most abundant in dry and early wet seasons.

Food and Feeding. Diet of the Central American Squirrel Monkey includes fruits, nectar, and animal prey, including larval, pupal, and adult insects, bird eggs and nestlings, anole lizards, tree frogs, and bats. Squirrel monkeys are foliage gleaners, animal prey dominates their diets. Most prey is found in dead or living furled leaves (spiders and grasshoppers) or is effectively sessile (caterpillars, pupae, and bird eggs). The most important families providing fruits include Melastomataceae , Rubiaceae , Musaceae , Vitaceae , and Piperaceae . Fruits are generally small and are available piecemeal, ripening gradually over prolonged periods. Most food items are small, dispersed, and unpredictable in their location. In Boinski’s study, less than 3% ofall feeding was dedicated to eating fruits or flowers in synchronized bouts in large tree crowns. In times of food scarcity, Central American Squirrel Monkeys increase their foraging time, so the amount of time that they spend feeding on arthropods varies little during the year. Fruit and nectar tend to be eaten more than expected based on availability and when insect abundance is low. Tent-making bats are an unusual food item of the Central American Squirrel Monkey. They recognize the “tents” made by certain phyllostomid bats up to 20 m away. These bats bite bases of lateral nerves of large leaves of species of Marantaceae , Araceae , Musaceae , Cyclanthaceae , and Heliconiaceae , causing leaves to collapse and form a tent around the mid rib. One to 50 bats may be found in these refuges, depending on the species. Three tent-making bats occur in Corcovado National Park: Thomas's Fruit-eating Bat (Artibeus watsoni), the Common Tent-making Bat (Uroderma bilobatum), and the Southern Little Yellow-eared Bat (Vampyressa pusilla). These bats are sensitive to vibrations of the foliage around them and cannot be stalked, so squirrel monkeys leap at the tents. Often tents are empty because these bats make and variably use a series of tents scattered through the forest. When a 4year-old male Central American Squirrel Monkey captured a juvenile fruit-eating bat, it knocked the bat to the ground and then seized and killed it with seven bites to the head. The male took it up to a branch and ate it rapidly (1 minute and 40 seconds). Sometimes squirrel monkeys find spherical nests of paper wasps (Polybia) in the bat tents. They leap repeatedly at the tents to knock the wasp nest to the ground. After each leap, they fall to the ground and roll away several meters to avoid being stung. When the wasp nest falls and breaks, the squirrel monkeys grab a piece of it and eat the larvae. Female Central American Squirrel Monkeys are rapid and avid eaters and rest less frequently than males. Males spend less time feeding and more time in sexual interactions and investigations and vigilance for predators.

Breeding. In Corcovado National Park, the mating season of the Central American Squirrel Monkey occurs in the mid-wet season from August to early October. Males are sexually mature at 2-5-3-5 years old. In June, about two months prior to the mating season, males begin to increase in bodysize, associated with high levels of thyroid hormones, steroids, and testosterone. Males may increase their weight by as much as 20%, and testicular volume and spermatogenic activity also increase. Older males become larger than younger males. During the mating season, up to 16 males (including some that are sexually immature) chase and mob females to smell their genitalia to assess their sexual receptivity. If not receptive, a female rejects males’ advances. Receptive females engage in mutual genital sniffing and follow and solicit copulations from the largest resident male. Evidence indicates that a female restricts her mating to just one male through an ovulatory cycle, which suggests that sperm competition does not occur. Sperm forms a copulatory plug that lasts several hours. Sometimes the largest male apparently hides (after having mated several times already that day) or is involved with another female, and another receptive female ends up mating with another resident male. The largest male copulates most and achieves an almost total monopoly of fully adult females. His supremacy as the largest male of the group only lasts one or two mating seasons. Sometimes a band of males from a neighboring group briefly infiltrates the group, and some of them copulate with females during the melee. Based on swelling of vaginal labia and the switch from rejection to solicitation, the period of sexual receptivity (periovulatory) is c.6-8 days. After gestation of 152-168 days, a female gives birth to a single young in the dry season (February-April) when food availability is increasing. Births are tightly synchronized, with the large majority occurring in the same week within each group (groups may synchronize in different weeks). Births of Central American Squirrel Monkeys are believed to be timed so that infants are weaned during the wet season when fruit is most abundant. Tight synchrony of birthsis also associated with cooperative vigilance for aerial predators by all females. Vigilance increases significantly when groups have neonates and numbers of raptors accompanying monkeys increase at this time. Chestnut-mandibled toucans (Ramphastos ambiguus swainsonii), ornate hawk-eagle (Spizaetus ornatus), and collared forest-falcons (Micrastur semitorquatus) have been seen to take neonates and infants. Allocare (females other than the mother carrying the young) is uncommon, Interbirth intervals are one year. Individuals have lived more than twelve years in captivity.

Activity patterns. In her studies in Corcovado National Park, Boinski found that travel time of Central American Squirrel Monkeys was small and tended to occur in early morning between 05:00 h and 06:30 h. Their day is dominated entirely by foraging. Groups move gradually through the lower canopy and understory, foraging almost constantly for animal prey and occasionally eating fruits. Foraging tends to decrease as the morning progresses (09:00-12:30 h), with an increasing proportion of the group resting from 11:00 h to 14:30 h. Stationary resting peaks at around midday. Their foraging is almost constant through midto late afternoon until ¢.18:00 h when they settle down to sleep. For two years, Boinski found that the study group used only two sleeping locations, and during more than one of those years, they usedjust three trees. Sleeping sites are trees with crowns nearly isolated from the surrounding canopy, evidently limiting access by predators to one or very few routes. It is possible that the few appropriate sleeping trees may be a limiting factor in home range size and even group size. In all seasons, little time is spent purely in travel (less than 3%), but Boinski found that time spent foraging changed according to food availability. In the late wet season, a time of food scarcity, an individual (aged 18 months or older) spent an average of 64% of its time searching for or eating food. At other times when food was more abundant, time spent foraging dropped to 43-47%. Boinski distinguished group activity categories as “travel forage,” “stationary forage,” ” «“stationary, rest, and forage,” and “stationary rest.” At times of extreme food scarcity, Central American Squirrel Monkeys may spend up to 95% their day looking for food, as was found by Boinski in Costa Rica and J. D. Baldwin and J. Baldwin in their late wet season study in Panama. Foraging at this time consists almost entirely of travel forage (c.56%) and stationary forage (c.37%). Travel foraging counted for only a little less of their time in the dry season and early and middle wet seasons, but stationary foraging dropped considerably (c.16% or less). When food was more abundant, stationary, rest, and foraging took up 22-28% of the day, and stationary resting up to 10%. Time spent in activities other than foraging varied enormously: lowest during the late wet season (1:8%) and highest during the early wet season (40-5%).

Movements, Home range and Social organization. Central American Squirrel Monkeys live in multimale-multifemale groups of 35-65 individuals. The size of the main study group of Boinski was 38-45 individuals, including ten adult males and 16 adult females. In Panama, mean group size is 18-5 individuals (range of 4-40). Males are philopatric, but females disperse before their first mating season and transfer between groups. Males do not form all-male groups as they do in Black-capped Squirrel Monkeys (S. boliviensis ). Interactions between individuals in the group are marked by an almost total lack of aggression. Exceptions are in sexual contexts, during weaning, and in some cases warding off over-curious individuals trying to investigate newborn infants. Females interact very little and do not form coalitions or hierarchies as they do in the Guianan Squirrel Monkey (S. sciureus ) and the Black-capped Squirrel Monkey. Direct competition for food among Central American Squirrel Monkeys is very rare; competition is avoided indirectly by maintaining distance among group members when foraging. Some degree of aggression occurs when groups of males mob a female, trying to smell her genitalia and mate with her. There is no hierarchy among males that can be perceived during such aggression, avoidance, or competition over food. Males cooperate when mobbing or chasing females. There is, however, a ranking evident during the mating season with regard to size, female choice, and successful copulations. The largest adult males show a consistently high investment in vigilance for predators and in direct interventions of possible or real threats to neonates and other group members. Depending on the season, aerial vigilance by the largest adult males takes up 3-5% of their day, two to four times more than adult females. Most reproductively successful males retrieve neonates and infants and also show aggressive defense against would be predators. The home range size of Boinski’s main study group of 38-45 Central American Squirrel Monkeys was 176 ha. Home ranges of adjacent groups overlapped, but neighboring groups very rarely met. When approaching each other, within 100-150 m, groups tended to veer off in different directions. They used some parts of the home range more than others in different seasons, and there was no evidence of a core area of use. They tended to travel further and quicker when food was scarce (350-400 m/h) and less when it was abundant (100-250 m/h). In the late wet season when food is scarce, the group was more dispersed when traveling and foraging (over 1-6 ha) than it was in the early wet season when food was more abundant (0-9 ha). This probably reflected a greater need to avoid indirect competition when food is harder to come by. The large size of the groups and the small size of squirrel monkeys make them prey to numerous raptors, mammals, and snakes, including Virginia Opposums (Didelphis virginiana), Central American Spider Monkeys (At eles geoffroyi), Panamanian White-faced Capuchins ( Cebus imitator ), White-nosed Coatis (Nasua narica), Tayras (Eira barbara), collared forest falcons (Micrastur semitorquatus), Guiana crested eagles (Morphnus guianensis), and snakes such as boa constrictors (Boa constrictor) and fer-de-lance (Bothrops asper). Other predators in Costa Rica and Panama include toucans, ornate hawk-eagles (Spizaetus ornatus), gray hawks (Buteo nitidus), roadside hawks (B. magnirostris), white hawks (Leucopternis albicollis), and red-throated caracaras (Daptrius americanus). Squirrel monkeys act as “beaters” by flushing prey for double-toothed kites (Harpagus bidentatus), tawny-winged woodcreepers (Dendrocincla anabatina), and gray-headed tanagers (Eucometis pencillata). These species regularly accompany groups of squirrel monkeys throughout the year and especially during the late wet season when animal prey is most scarce. Numerous other species occasionally follow groups of squirrel monkeys for this reason. Double-toothed kites catch tent making bats when they are flushed by squirrel monkeys.

Status and Conservation. CITES Appendix I. Classified as Vulnerable on The IUCN Red List, with both subspecies oerstedii and citrinellus classified as Endangered. The main reason for the considerable decline in numbers of the Central American Squirrel Monkey has been loss of habitat due to deforestation and tourist development; their natural shyness makes them easily stressed by tourists. Individuals rarely descend to the ground: therefore, any break in the forest (such as for roads or telephone and electric power lines) can severely fragment a group’s habitat. It is also threatened by widespread spraying of insecticides. Only a few fragmented populations remain. In 1997-1998, Boinski estimated less than 4000 Central American Squirrel Monkeys in Costa Rica, including c.1000 individuals of the Gray-crowned Central American Squirrel Monkey. Boinski indicated that they were probably extinct in Panama, but recent surveys found a fragmented population of ¢.4775 Black-crowned Central American Squirrel Monkeys in Chiriqui Province, spread over 2613 km? in far western Panama. Although Corcovado National Park is 41,788 ha, it is believed to have no more than ¢.400 squirrel monkeys because they are restricted to areas that contain disturbed and secondary forest, which only cover ¢.20 km?® of the park. The Black-crowned Central American Squirrel Monkey also occurs in Golfito Wildlife Refuge (2830 ha). The Gray-crowned Central American Squirrel Monkey occurs in Manuel Antonio National Park (682 ha).

Bibliography. Arauz (1993), Baldwin (1971), Baldwin & Baldwin (1972, 1976a, 1981), Boinski (1987a, 1987b, 1987c, 1987d, 1988, 1994, 1999a, 1999b), Boinski & Cropp (1999), Boinski & Mitchell (1994), Boinski & Scott (1988), Boinski & Sirot (1997), Boinski & Timm (1985), Boinski et al. (1998), Janzen (1983), Matamoros & Seal (2001), Matamoros et al. (1996), Mitchell, C.L. et al. (1991), Rodriguez-Vargas (2003), Sierra et al. (2003), Wong (1990).

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.