Cebus imitator, Thomas, 1903

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6628559 |

|

DOI |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6628289 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/560F8786-B733-2840-0DC3-F5503801F520 |

|

treatment provided by |

Jonas |

|

scientific name |

Cebus imitator |

| status |

|

Panamanian White-faced Capuchin

French: Sapajou du Panama / German: Panama-Kapuzineraffe / Spanish: Capuchino de cara blanca de Panama

Other common names: \White-headed Capuchin, White-throated Capuchin

Taxonomy. Cebus imitator Thomas, 1903 View in CoL ,

Chiriqui, Boquete, Panama, elevation 1350 m.

Abundant scientific literature on this species refers to it as C. capucinus . In his 1949 review of the Colombian capuchins, P. Hershkovitz listed the form lOmitaneus from the eastern border between Honduras and Nicaragua. It was also recognized by W. C. O. Hill in 1960 and E. R. Hall in 1981. It was believed to be a smaller race than imitator with a smaller skull. Hershkovitz was not convinced that it was a separate taxon, and J. Boubli and M. Ruiz-Garcia and their coworkers independently concluded that it was genetically indistinguishable from C. imitator and, having been described in 1914, is a junior synonym. Individuals from Honduras have frosted yellow on their inner thighs. Monotypic.

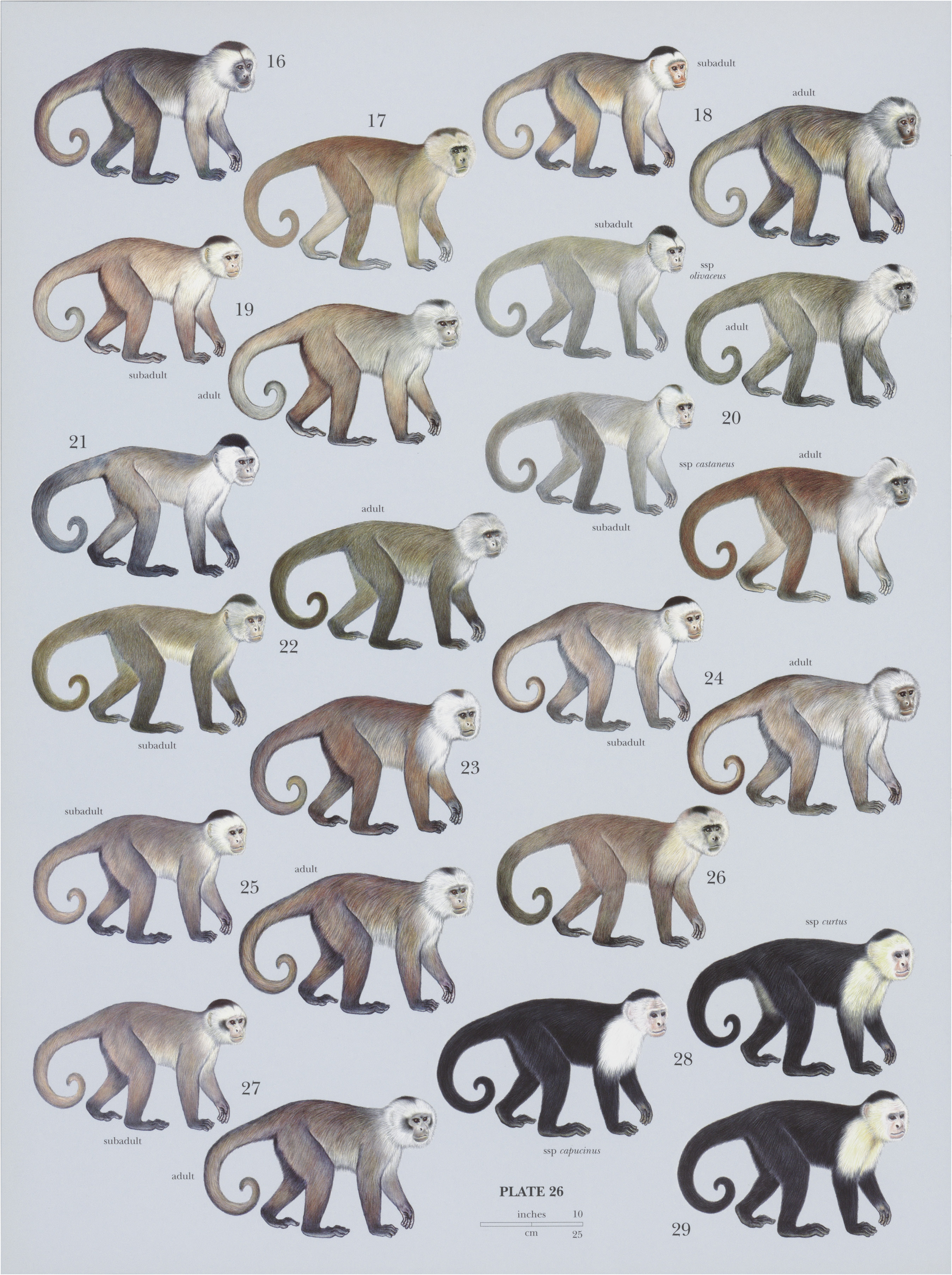

Distribution. N Honduras, C & W Nicaragua, Costa Rica, and W Panama (including Coiba and Jicaron Is); reports of capuchins in the Mayan Mountains of W Belize (Chiquebul forest and in the region of the Trio and Bladen branches of the Monkey River), Sarstoon National Park on the S border, and in the Sierra del Espiritu Santo near the Honduras border have not been confirmed. View Figure

Descriptive notes. Head-body 34:3-42 cm (males) and 38:5-40.5 cm (females), tail 44-46 cm (males) and 43-45 cm (females); weight 3.7-3.9 kg (males) and 2.6-2.7 kg (females). Male Panamanian White-faced Capuchins are ¢.27% larger than females. The Panamanian White-faced Capuchin resembles the typical Colombian White-faced Capuchin (C. c. capucinus ), but females have elongated frontal tufts with hairs ¢.40 mm long, with a brownish tinge contrasting with the white of the cheeks and throat, entirely altering the facial appearance.

Habitat. Lowland, submontane, and montane moist forests from sea level to 1500 m and mosaics of tropical dry forest patches and gallery forest in different stages of regeneration, with severe dry seasons and annual rainfall less than 1700 mm. On the Caribbean coast, annual rainfall can exceed 5000 mm. Panamanian White-faced Capuchin enter mangrove swamps.

Food and Feeding. Diet of the Panamanian White-faced Capuchin includes fruits, insects, snails, crabs, clams, slugs, frogs, lizards (Anolis and Ctenosaura), nestling and adult birds, nestling and adult Variegated Squirrels (Sciurus variegatoides), White-nosed Coati pups (Nasua narica), and tree rats. Predation on coati pups occurs in April-May when coatis are breeding. When coati nests are defended, Panamanian White-faced Capuchins cooperate, with some individuals baiting and distracting adult coatis and others grabbing pups. They also eat eggs of various birds, including curassows, guans, magpie jays, nightjars, tinamous, woodpeckers, wrens, herons, and wood ducks. Flowers, leaves, flower and leaf buds, stems and roots, and nectar are also eaten. When foraging for animal prey, Panamanian White-faced Capuchins extensively search leaf litter, the underside of leaves, curled leaves, rotten wood, dead leaves, fallen branches, and open hollow vines and thorns. On Barro Colorado Island, Panama, fruits are least abundant in November—February, and they eat more apical meristems and succulent bases of new shoots. Panamanian White-faced Capuchins especially like to eat larvae and nymphs of beetles, butterflies, moths and spittlebugs, and they attack ant and wasp nests. They rub larvae against branches to remove spines or poisonous hairs, and sometimes they also wrap them in a leaf before rubbing them. Individuals that capture larger prey are only minimally harassed for a share by other group members that are content with bits dropped or abandoned. Panamanian White-faced Capuchins drink water, often from tree holes. Water sources in the dry season can be rare, and daily access to them restricts their movements. Sometimes more than one group uses the same pool to drink, causing tense meetings between groups.

Breeding. When courting, female Panamanian White-faced Capuchins do not raise their eyebrows and grimace as do female Sapajus . Instead, they make a so-called “duckface” with lips protruded while looking at their prospective partner. They also have a courtship dance. Pairs pirouette and face away, and then look at each other (mutual gazing) over their shoulders or through their legs. There is a specific call given at this time. Females court and mate throughout the year and in all reproductive states, even when pregnant. Males frequently sniff females’ urine and are more likely to respond when a female is close to ovulating. Females mate with the alpha males more than with subordinates and do so more when fertile. They mate with subordinate males more when they are infertile. Births of Panamanian White-faced Capuchins occur throughout the year but are more common in the dry season. All group males mate but most infants are sired by the alpha male (63-84%). Average interbirth interval for females that have successfully raised their offspring is 27-5 months. If an infant dies (not in the context of a male takeover), interbirth interval drops to 12-3 months. When an infant dies during or after a male takeover, interbirth interval is a little longer at c¢.15-7 months. Females first give birth at about seven years old and males reach reproductive maturity at about ten years. In captivity, they have been known to live for nearly 55 years.

Activity patterns. Panamanian White-faced Capuchins are active most of the day, starting at or a little before dawn, and rest for a while at midday. Groups in humid (but seasonal) forests of Barro Colorado Island have a general daily pattern of 28% foraging (looking for, handling, and eating food), 47% traveling, 14% resting, and 11% grooming, playing, and engaging in other activities. In dry forest at Santa Rosa National Park, Costa Rica, foraging takes up more time (41%), traveling less (37%), and resting more (21%), with very little time in social activities. In the wet season, Panamanian Whitefaced Capuchins spend about the same amount of time foraging for plant foods (21%) as they do for animal prey (22%), but in the dry season, foraging for plant food takes up 26% of the day and animal prey 10-5%. They often go to the ground to forage, drink water, or move between patches of trees. They sleep at the ends of the branches in large tall trees. Groups generally do not sleep in the same site on consecutive nights.

Movements, Home range and Social organization. Group sizes of Panamanian Whitefaced Capuchins average c.16, and adult sex ratios of c.0-7 male:1 female. During five years, a group studied by J. Oppenheimer on Barro Colorado Island had 1-3 adult males and 5-7 adult females. Their home range was 164 ha, with a core area of 87-8 ha where most of their time was spent. Home ranges, but not core areas, overlap, and when groups (infrequently) meet, there are aggressive displays, particularly by males. Females typically remain in their natal group and males disperse. Females and males form independent dominance hierarchies, and the alpha female is subordinate only to the alpha male. She dominates subordinate males. Females form coalitions and together they can displace the alpha male at disputed food sources. Females tend to threaten males more than females, and they receive fewer threats than they give. Males do not form all-male groups, and when males move into another group and displace resident males, it is quite rapid and generally violent, sometimes involving fatalities. Males may transfer between groups several times in their lifetimes, either singly or in coalitions of as many as two other males that are sometimes siblings. Overall, 67-80% of all emigrations involve parallel dispersal (two or more males transferring groups together). Dispersals of these coalitions are robust, and a coalition can last for several transfers; residency of coalitions in any one group is longer than individually dispersing males. Sometimes males transfer to a new group peacefully and unobtrusively, without contesting the existing male hierarchy, but when they are aggressive and involve the replacement of the alpha male, they are associated with the wounding, death, and disappearance of infants. Most male takeovers of groups occur during the dry season, and ¢.82% of the infants that are less than one year old die (average age of death is 4-4 months) after the takeover. In years when there is no male takeover, c.2% of infants die. Males spend more time scanning the environment than females, but they are less concerned with predators than they are with detecting takeover threats from outside males and with monitoring males in their own group. Unlike other capuchins, Panamanian White-faced Capuchins rarely associate with squirrel monkeys ( Saimiri ) where they are sympatric (e.g. Corcovado National Park, Costa Rica). This is probably because squirrel monkeys would gain little from increased predator detection by the capuchins, and the particularly predaceous capuchins would interfere with the squirrel monkeys’ foraging. Predators include snakes (Boa constrictor), large cats (Panthera onca, Puma concolor), small cats (Puma yaguaroundi and possibly Leopardus pardalis and L. wiedn), Tayra (Eira barbara), Coyotes (Canis latrans), spectacled caimans (Caiman crocodilus), and raptors, including the great black hawk (Buteogallus urubitinga). Panamanian White-faced Capuchins give alarm calls that are specific to aerial and terrestrial predators. When detected close, terrestrial predators are mobbed and chased.

Status and Conservation. CITES Appendix II. Classified as Least Concern on The IUCN Red List (as C. capucinus imitator ). The Panamanian White-faced Capuchin occurs in numerous protected areas: La Amistad International Park (Panama/Costa Rica), Braulio Carillo, Chirripo, Corcovado, Guanacaste, Palo Verde, Piedras Blancas, Rincon de la Vieja, Santa Rosa, Tortuguero, and Volcan Poas national parks, Lomas Barbudal Biological Reserve, and Cabo Blanco Strict Nature Reserve in Costa Rica; Cerro Hoya, Coiba Island, Soberania, Altos de Campana, Soberania, Omar Torrijos Herrera-El Copé, and Volcan Baru national parks and Barro Colorado National Monument in Panama; and Pico Bonito, Jeanette Kawas, Cusuco, Montana de Yoro, Sierra de Agalta, and Punta Izopo national parks in Honduras.

Bibliography. Boubli et al. (2012), Defler (2003b, 2004), Fedigan (2003), Fedigan & Jack (2004), Fedigan & Rose (1995), Fragaszy, Fedigan & Visalberghi (2004), Fragaszy, Visalberghi et al. (2004), Freese (1977), Freese & Oppenheimer (1981), Gros-Louis (2002), Gros-Louis et al. (2003), Hall (1981), Hershkovitz (1949), Hill (1960), Jack (2011), Jack & Fedigan (2004a, 2004b), Manson et al. (1999), Matamoros & Seal (2001), Milton & Mittermeier (1977), Newcomer & de Farcy (1985), Oppenheimer (1968, 1973, 1982), Panger et al. (2002), Perry, (1996), Perry & Rose (1994), Rose & Fedigan (1995), Rose et al. (2003), Ruiz-Garcia et al. (2012), Rylands etal. (2006), Silva-Lopez et al. (1995), Thomas (1903).

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.