Sicista concolor (Büchner, 1892)

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/ 10.5281/zenodo.6603557 |

|

DOI |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6603417 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/6561A655-FFBB-FF88-FF00-F421FC10BA38 |

|

treatment provided by |

Felipe |

|

scientific name |

Sicista concolor |

| status |

|

Chinese Birch Mouse

French: Siciste de Chine / German: China-Birkenmaus / Spanish: Raton listado de China

Other common names: Gansu Birch Mouse (concolor, Kashmir Birch Mouse (leathemi), Sichuan Birch Mouse (weigoldi)

Taxonomy. Sminthus concolor Buchner, 1892 ,

Guiduisha , N slope of Xining (= Sining) mountains, Gansu, China.

Eastern Montane Species Group. The southern Asian population (leathemi) is provisionally recognized here as a valid subspecies based on morphological characters such as a relatively long tail and geographical isolation precluding gene flow between Chinese and south Asian populations. Because flavus was described later from the same geographical region inhabited by leathemi and is known only from the type specimen, it is treated here as a junior synonym of leathemi. Zhang Rongzu in 2004 discussed effects of Pleistocene climate fluctuation and glaciation on past and present distributions of land vertebrates in China. During colder periods, glaciers existed predominantly in high mountains along eastern margins of the Tibetan Plateau, and distributions of certain alpine Palearctic species shifted their distributions as far south as mountains in south-central China. As glaciers retreated, relict montane populations of alpine and boreal-adapted species survived in isolated montane refugia, and he categorized these populations as boreal-alpine relicts. Although his discussion of S. concoloris outdated in terms of systematics of the genus, he was correct to note that populations of S. concolor that have persisted in high montane refugia are likely relictual. Because the south-central Chinese populations (weigoldi) have been characterized by morphological differences and because that region supports a high level of endemism due to complex topography, past vicariance events, and unique and intertwined ecozones, weigoldiis provisionally recognized here, and the Sichuan and Yunnan populations are assigned to this subspecies. T. Cserkész and colleagues in 2017 resolved a number ofspecific relationships based on combined phylogenetic analyses of sequences of mtDNA control region and cytochrome-b with nuclear interphotoreceptor binding protein (IRBP) genes. Their results indicated weak statistical support for basal position of S. tianshanica , followed by divergence of S. concolor ; however, based on morphology of glans penis, S. concolor should be the basal species in the genus because its morphotype is the most primitive in the genus. A specimen collected in northern Xinjiang Province initially identified as S. concolor by Zhang Qian and colleagues in 2012 likely represents S. pseudonapaea . Three subspecies recognized.

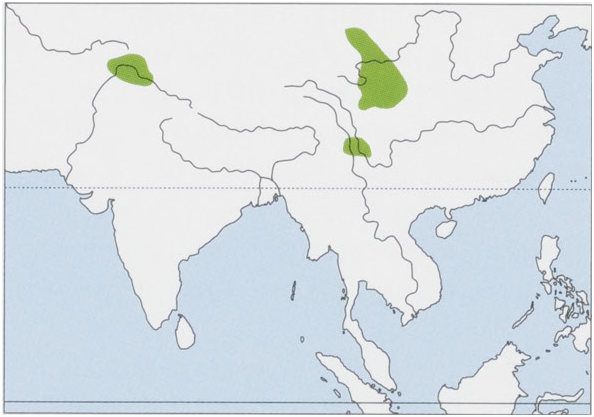

Subspecies and Distribution.

S.c.concolorBuchner,1892—NCChinainEQinghai,Gansu,andSWShaanxi.

S. c. weigoldiJacobi, 1923 — SC China in NW & NC Sichuan and NW Yunnan. View Figure

Descriptive notes. Head—body 51-76 mm, tail 86-109 mm, ear 11-14 mm, hindfoot 17-18 mm; weight 5-8 g. Dorsum of the Chinese Birch Mouse is brown in Gansu and Sichuan populations and varies from rufous brown and grayish brown to yellowish brown in Kashmir population; conspicuous black guard hairs make backs appear dark. Venter is grayish white and not clearly demarcated from dorsum. Sides of body and cheeks appear paler and brighter due to absence of black-tipped guard hairs. Hindfoot is long, usually 22-28% of head-body length. Tail is long to very long; based on scant data, the “Sichuan Birch Mice” (S. ¢. weigoldi) might have the shortest tail length relative to head-body length at c.125%, the “Gansu Birch Mouse” (nominate concolor ) has a longer tail at ¢.140%, and the “Kashmir Birch Mouse” (S. ¢. leathemi) has the longesttail at c.160%. Tails of all three subspecies are bicolored, darker above, and paler beneath. Type specimen has uniformly colored tail, but all other individuals have bicolored tails. Greatest lengths of skulls are 19-20 mm, interorbital breadth is 4 mm, and length of upper tooth row is 3-1 mm. Chromosome numberis not known. External and cranial measurement for greatest length of skull were reported by A. T. Smith in 2008 and Smith and Yan Xie in 2013 from various localities in China; remaining cranial measurements from holotype collected in Xining Mountains, Gansu Province, were recorded by E. Buchner in 1892.

Habitat. Alpine birch ( Betula , Betulaceae ) forests, mixed birch-conifer forest margins, rhododendron (Rhododendron, Ericaceae ) forests, alpine and subalpine meadows, shrublands, steppes, and grasslands generally at elevations of 2743-3048 m. In eastern Qinghai Province, Ma Ying and colleagues in 2011 surveyed five habitats for small mammals and only captured Chinese Birch Mice in alpine shrub habitat. Sichuan Birch Mice have been captured at elevations of 3300-4027 m; one was captured in rhododendron forest at 4027 m near Maerkang (= Barkham) in north-western Sichuan by P. Giraudoux and F. Raoul in 2015. In southern Jiajin Mountains in north-western Sichuan, Tu Feiyun and colleagues in 2012 recorded them in coniferous and broadleaf mixed forests at 3300-3600 m and deciduous forests, coniferous forests, and subalpine meadows and scrubland from 3300 m to more than 3600 m. Holotype of the Kashmir Birch Mouse was collected in the Wardwan (= Warwan), Krishnye Valley, India, at 3048 m. The type specimen of what is treated here as a junior synonym, flavus, was captured in central Kashmir, India, at 3353 m. In Pakistan, Kashmir Birch Mice have been recorded in terraced cultivated fields on upper slopes of valleys, subalpine scrubland, alpine pastureland, alpine meadows and grassy slopes, and tundra habitats at elevations of 2140-4000 m in the western Himalayas, eastern Hindu Kush, and the Karakoram-Pamir Landscape that straddles north-eastern Pakistan and south-western Xinjiang, China.

Food and Feeding. Little is known, but the Kashmir Birch Mice reportedly consumes berries, wild fruit, seeds, fungi, and insects. They have been captured in ripening maize fields and observed gnawing on maize cobs.

Breeding. Mating activity of the Chinese Birch Mouse likely starts immediately after hibernation. Kashmir Birch Mice are believed to produce a single litter of 3-6 young/year. A pregnant female trapped in late July in Kaghan Valley, northern Pakistan had four embryos, as reported by T.J. Roberts in 1997; another female trapped in late August was lactating. He also noted that females constructed breeding nests from a neatly woven ball of grass, located in crevices or bushes, and young left nests at c.4 weeks of age.

Activity patterns. Chinese Birch Mice are nocturnal and likely also crepuscular. Like other species of Sicista , they hibernate in winter, but when hibernation begins and ends is unknown.

Movements, Home range and Social organization. Chinese Birch Mice are solitary. In north-eastern Gansu, they have been reported as pests. Trapping, use of rodenticides, and other measures are used to control densities; nevertheless, Chinese Birch Mice have only been found in high enough densities to warrant extermination at 1-2 localities throughoutits vast distribution. In eastern Qinghai, they comprised 3-9% of all rodents, shrews, and lagomorphs captured in alpine shrub. According to Tu Feiyun and colleagues, Chinese Birch Mice are rare on southern slopes ofJiajin Mountains in north-western Sichuan and were more common on northern slopes; abundance varied by habitat. Only one Chinese Birch Mice was captured from 131 rodents, shrews, and lagomorphs in deciduousforests (percent relative frequency of 0-76%); four of 74 in coniferousforests (5-4%); and two of 24 in subalpine meadows and scrub (8:3%); all habitats were above 3300 m, with the greatest number of Chinese Birch Mice captured above 3600 m.

Status and Conservation. Classified as Least Concern on The IUCN Red Lust. Justification for this classification was based on the wide distribution of the Chinese Birch Mouse and presumption that population sizes are not declining fast enough to qualify for a more threatened category. Nevertheless, Chinese Birch Mice are rarely encountered and likely only locally common. Future studies may support recognition of one or more of the three subspecies as separate valid species.

Bibliography. Ahmed et al. (2013), Allen (1940), Baskevich (2016), Buchner (1892), Chakraborty (1983), Cserkesz, Fulop et al. (2017), Cserkész, Rusin & Sramkoé (2016), Ellerman (1961), Giraudoux & Raoul (2015), Khan, B. et al. (2012), Khan, M.Z. et al. (2013), Li Huafeng & Zhang Baozhi (2005), Ma Ying et al. (2011), Molur (2016a), Molur et al. (2005), Nawaz (2008), Ning Wu et al. (2014), Ognev (1948), Roberts (1997, 2005), Smith (2008a), Smith & Yan Xie (2013), Srinivasulu & Srinivasulu (2012), True (1894a), Tu Feiyun et al. (2012), Vaniscotte et al. (2009), VWWang Sung et al. (1989), Woods et al. (1997), Zhang Qian et al. (2013), Zhang Rongzu (2004).

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.