Bassaricyon alleni, Thomas, 1880

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.5714404 |

|

DOI |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.5714743 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/6A61FC4E-FFAF-0148-1CCA-FE3A6EF1D350 |

|

treatment provided by |

Conny |

|

scientific name |

Bassaricyon alleni |

| status |

|

Lowland Olingo

Bassaricyon alleni View in CoL

French: Olingo d’'Allen / German: Makibar / Spanish: Olingo de Allen

Taxonomy. Bassaricyon alleni Thomas, 1880 View in CoL ,

Sarayacu, on the Bobonasa river, Upper Pastasa river [ Ecuador].

The Lowland Olingo was initially described as five different species but is now recognized as one broadly ranging olingo with three subspecies.

Subspecies and Distribution.

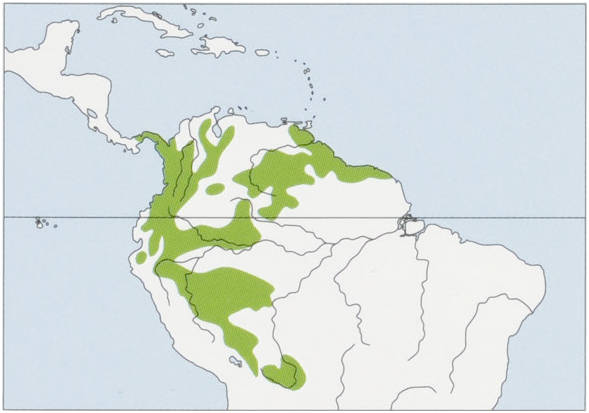

B. a. alleni Thomas, 1880 — South America, E of the Andes.

B. a. medius Thomas, 1909 — Choc6 region of W Colombia, Ecuador, and NW Venezuela.

B. a. orinomus Goldman, 1912 — E Panama. View Figure

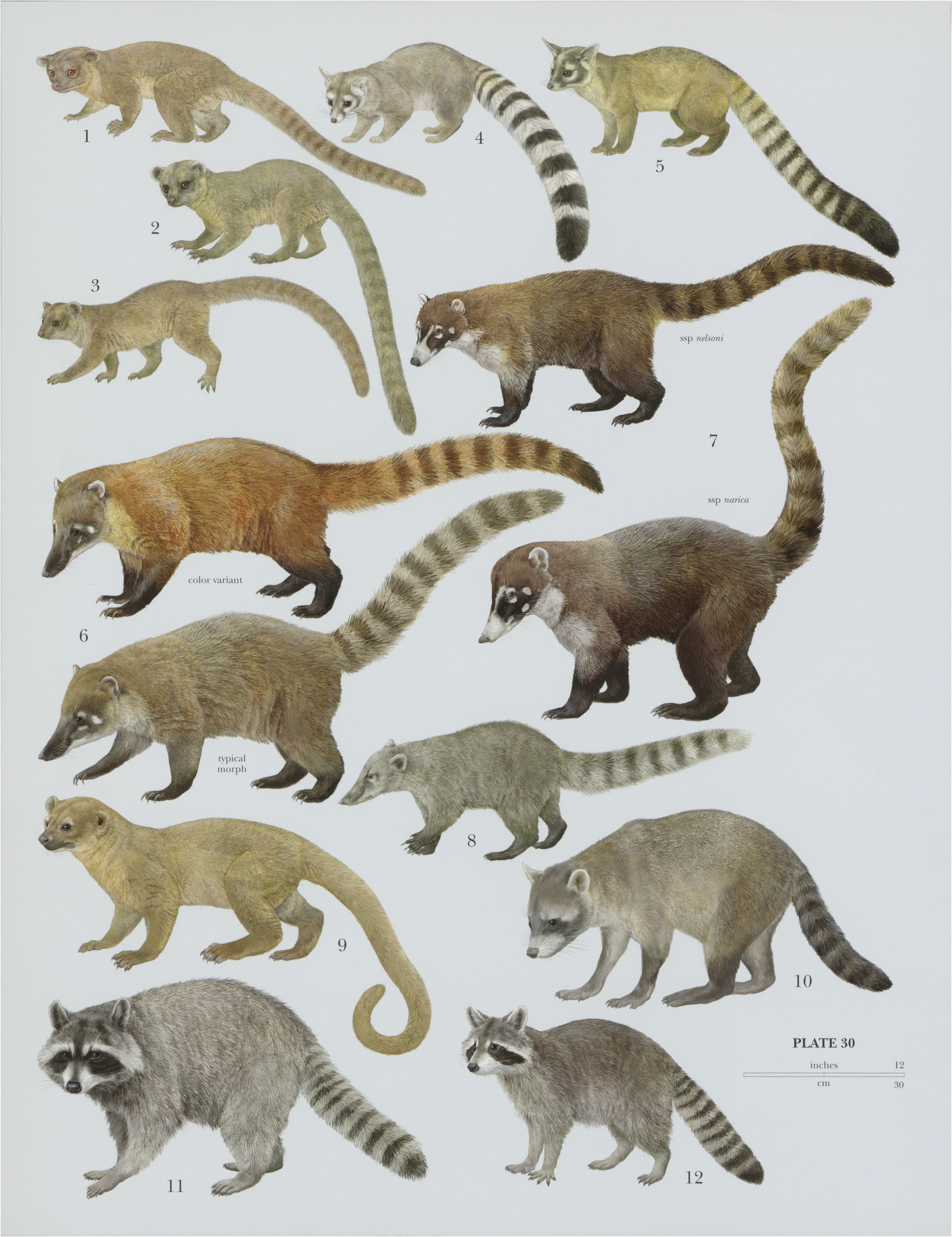

Descriptive notes. Head-body 30-49 cm, tail 35-53 cm; weight 0.9-1.6 kg. Olingos are tawny brown in color with long tails that sometimes appear ringed. They are often mistaken for Kinkajous when glimpsed at night through the canopy vegetation. Kinkajous are approximately twice the weight of olingos, although overall length is similar, making size an unreliable indicator for identifying animals running through the trees. The two species can be distinguished even under field conditions by key characters of the snout, lateral line, and tail. Olingos are different from Kinkajous in having a more pointed snout with gray fur, and a sharper lateral line separating their darker back and lighter-colored belly. Olingo tails are much bushier than the muscular tail of a Kinkajou, and sometimes show faint rings. Finally, the tail of an olingo is not prehensile, so is only used to balance, and can not grab branches as Kinkajous frequently do. Olingos also have a similar body form to Cacomistles, but are differentiated in being browner (not gray) with a slimmer tail that has only faint annulations.

Habitat. The Lowland Olingo is found in moist tropical forests up to 1800 m, but usually below 1500 m.

Food and Feeding. Olingos are primarily frugivorous and the extent to which they also hunt prey is uncertain. Reports from the field only describe olingos consuming fruits and flowers, but information from captivity, and dental morphology, suggest they may also consume insects or other small prey. They have been recorded feeding on the same fruit and flower resources as Kinkajous in Panama and Peru, and were sometimes displaced from feeding trees by aggressive Kinkajous.

Activity patterns. Olingos are completely arboreal and primarily nocturnal, spending daylight hours resting in tree holes or other arboreal den sites.

Movements, Home range and Social organization. Movement data are only available for one male olingo that used a home range of 37 ha and moved 4-5 km per night. Their social organization is not described, but they appear to be more solitary than Kinkajous. Social vocalizations and scent marking have been recorded in captivity. A long-distance call has been described from a variety of field workers variously as a “whey-chuck”, “wer-toll”, and “wake-up”.

Breeding. Olingo reproductive behavior is well described from captive animals. They are polyestrous, with an estrous cycle of 24 days. Matings take place during one to three consecutive nights and copulations can last up to 68 minutes. The gestation period is about 74 days,after which one young is born. Pups can stand up after about three weeks and walk well after ten weeks, but require three to five months to develop climbing skills. Independent feeding starts at about seven weeks.

Status and Conservation. Olingos are classified by The [UCN Red List as Least Concern, but seem to occur at lower densities and be more sensitive to disturbance than other procyonids.

Bibliography. Garza et al. (2000), Janson & Emmons (1990), Kays (1999b, 2000), Mendes & Chivers (2002), Poglayen-Neuwall (1976a, 1973, 1989), Redford & Stearman (1993).

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.

|

Kingdom |

|

|

Phylum |

|

|

Class |

|

|

Order |

|

|

Family |

|

|

Genus |

Bassaricyon alleni

| Don E. Wilson & Russell A. Mittermeier 2009 |

Bassaricyon alleni

| Thomas 1880 |