Dasypus novemcinctus, Linnaeus, 1758

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6631721 |

|

DOI |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6629400 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/754587D9-FFFF-CA78-FF5C-F5012BCDF780 |

|

treatment provided by |

Valdenar |

|

scientific name |

Dasypus novemcinctus |

| status |

|

1 View Plate . View Plate 1: Dasypodidae

Nine-banded Armadillo

Dasypus novemcinctus View in CoL

French: Tatou a neuf bandes / German: Neunbinden-Girteltier / Spanish: Mulita de nueve bandas

Other common names: Common Long-nosed Armadillo

Taxonomy. Dasypus novemcinctus Lin- naeus, 1758 View in CoL ,

“in America meridionali.” Restricted by A. Cabrera in 1958 to Per- nambuco, Brazil.

There are two issues regarding the taxon- omy of D. novemcinctus . First, while there rarely have been instances where specimens of D. novemcinctus were misidentified, on multiple occasions specimens of other, smaller species have been misclassified as D. novemcinctus , probably because

of their striking resemblance to the juvenile form of D. novemcinctus . Second, there are conflicting reports about the number of subspecies. Of the six subspecies recognized, only four were supported by recent analyses. More work is needed to reconcile these new findings with previous classifications.

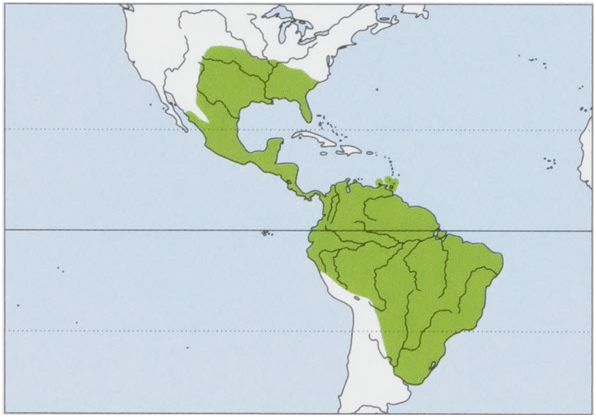

Subspecies and Distribution.

D.n.aequatorialisL.onnberg,1913—WAndeanslopefromColombiatoNWPeru.

D.n.davis:Russell,1953—WMexico,fromNSinaloaStoGuerrerostates.

D.n.mexianaeHagmann,1908—AmazonDelta,ParaState,Brazil.

D. n. mexicanus Peters, 1864 — C, S & SE USA, E & S Mexico, Belize, and Guatemala. Also present in El Salvador, but subspecies involved not known. View Figure

Descriptive notes. Head-body 360-570 mm, tail 260-450 mm, ear 25-57 mm, hindfoot 80-110 mm; weight 3-6 kg. Although called the Nine-banded Armadillo, number of bands on carapace is not considered a very reliable characteristic because it can range from seven to eleven. It is a relatively large species, second only to the Greater Long-nosed Armadillo ( D. kappleri ) in body weight. Ears and tail are long relative to smaller species, and carapace is not as dark, often containing areas of tan or pale yellow on sides of body. Chromosomal complement is 2n = 64, FN = 78 or 80.

Habitat. Most commonly, primary, undisturbed hardwood forest in riparian areas up to elevations of 3000 m. The extremely large distribution of the Nine-banded Armadillo suggests that it can exploit a variety of habitats. In the USA, distribution is continuing to expand; habitat modeling analyses project that it may eventually occupy

areas up to 40° N and 102° W. Limits to its distribution in the USA and elsewhere are thought to reflect the need for warm, moist environments.

Food and Feeding. The Nine-banded Armadillo is a generalist insectivore, primarily eating adult and larval beetles, ants, and termites. Dietary analyses also have identified an impressive diversity of other items such as small vertebrates, fruits, worms, and bird and turtle eggs.

Breeding. In the USA, breeding of the Nine-banded Armadillo occurs in early summer (June—July), although nulliparous females breed later (September—October) than those that have bred before. Females typically pair with just one male, but males often pair with 2-3 females (at separate times) during the breeding season. Females ovulate a single egg. After fertilization, implantation is delayed, and the zygote is held in the fundus of the uterus until midto late autumn (November—December). Implantation can be delayed even longer understressful conditions, such as captivity, with reports of laboratory and zoo-housed females giving birth up to 2-3 yearsafter fertilization. Upon implantation, the fertilized egg splits in two, and these then split again to create four genetically identical embryos. Gestation is 120-130 days, and young are born in spring (March-April). Juveniles are nursed in underground burrows for c.6 weeks. They first appear aboveground in early to mid-summer (May-August), at which time they forage together (often in the absence of the mother) until litters begin to break up in early autumn. A similar seasonal pattern is assumed to occur outside the USA.

Activity patterns. Adult Nine-banded Armadillos are primarily nocturnal, but this varies seasonally, with individuals becoming more diurnal (i.e. in the afternoon) during colder times of the year. During their first summer aboveground, juveniles can be observed from late morning to early afternoon but adopt more of the adult activity pattern in late summer and autumn.

Movements, Home range and Social organization. Home ranges are 0-5-20 ha, with at least some ofthis variation due to density and habitat type (smaller home ranges in more dense populations and richer habitats). Most commonly, home ranges average 6-10 ha. Adult male and female home ranges are about the same size; home range overlap is extensive, although breeding males tend to have less overlap with one another. Except during the breeding season, adults are solitary and rarely interact. In contrast, juvenile littermates are commonly seen foraging together during their first summer aboveground. Mark-recapture data indicate that resident individuals in a population move 150-200 m between successive captures or re-sightings. Natal dispersal distances are largely unknown, and the ongoing distributional expansion of the Nine-banded Armadillo in the USA suggests some individuals might move substantial distances.

Status and Conservation. Classified as Least Concern on The IUCN Red List. Although the Nine-banded Armadillo is hunted for meat and killed as a pest, human activities do not seem to have negative impacts. Nevertheless, much less is known about the status of populations in Central and South America; thus, it is possible that some subspecies of the Nine-banded Armadillo might be in more jeopardy than is currently appreciated. Within the Americas, the Nine-banded Armadillo is the only vertebrate other than humans known to be a natural reservoir of Mycobacterium leprae, the causative agent in producing Hansen's disease (leprosy).

Bibliography. Billet et al. (2017), Cabrera (1958), Feng Xiao & Papes (2015), Feng Xiao, Anacleto & Papes (2017), Hautier et al. (2017), Layne & Glover (1985), Loughry & McDonough (2013), McBee & Baker (1982), McDonough (1997, 2000), Storrs et al. (1988), Taulman & Robbins (2014), Wetzel & Mondolfi (1979), Wetzel et al. (2008).

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.