Pennatomys nivalis, Turvey & Weksler & Morris & Nokkert, 2010, Turvey & Weksler & Morris & Nokkert, 2010

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1096-3642.2009.00628.x |

|

DOI |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.10545595 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/7C4E878A-AB73-FF81-609E-E67109AD8BAC |

|

treatment provided by |

Valdenar |

|

scientific name |

Pennatomys nivalis |

| status |

|

PENNATOMYS NIVALIS GEN. ET SP. NOV.

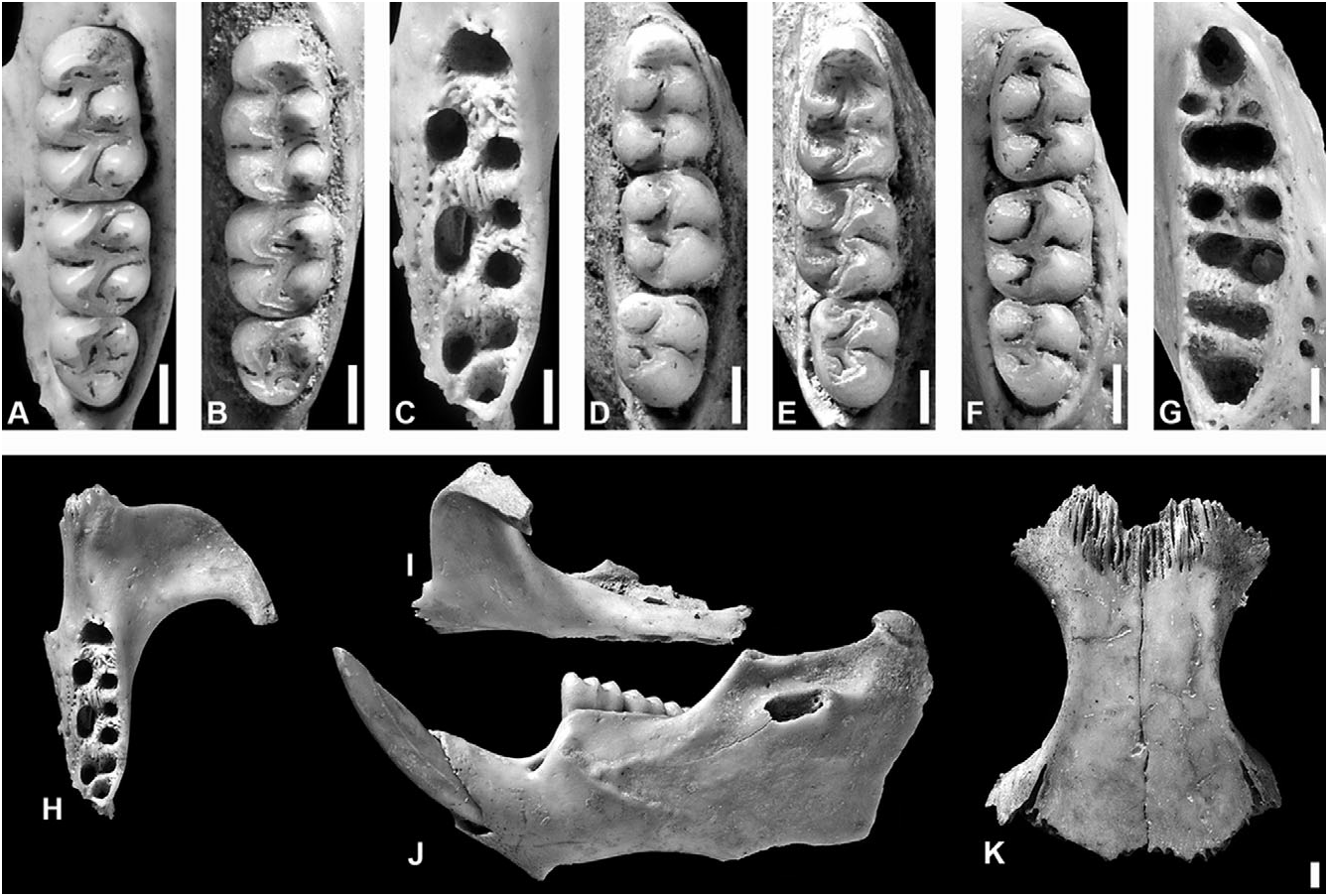

Holotype: NHM M 82452 , right hemimandible with i1 and m1–3 ( Fig. 10D View Figure 10 ).

Type locality: Hichmans (site GE-5 of Wilson, 2006), Saladoid-era Amerindian archaeological site, 100 BC–AD 600; test pit 14, spit 4/2, context 1363, sample BS 5402 (see Crosby, 2003 for specific site details); St. George, Gingerlands, Nevis , Federation of St. Kitts – Nevis.

Paratypes: Four hemimandibles ( NHM M 82453 , M 82454 , M 82459 , and M 82460 ) from test pit 14, spit 4/2, context 1363, sample BS 5402 ; one maxilla ( NHM M 82455) from test pit 14, spit 4/1, context 1362, sample BS 5344 ; one maxilla ( NHM M 82456 ), and one humerus and one femur ( NHM M 82458 ), from test pit 14, spit 2/2, context 1362, sample BS 5319 ; paired frontals with associated left nasal ( NHM M 82457 ) from test pit 14, spit 2/2, context 1362, sample DS 5322 ; one premaxilla with associated incisor ( NHM M 82461 ) from test pit 14, spit 5, context 1363, sample BS 5407 ; all from Hichmans ( Fig 10B, E View Figure 10 ) .

Examined specimens: In addition to the type series, additional dissociated craniodental and postcranial rice rat skeletal material was also examined from the archaeological sites of Sugar Factory Pier, St. Kitts ( FLMNH-EAP 02510001-02510008; see Wing, 1973); and Golden Rock, St. Eustatius ( FLMNH-EAP 05270001–05270005; see van der Klift, 1992).

Distribution: Known from late Holocene pre-Columbian zooarchaeological sites on the islands of St. Eustatius, St. Kitts, and Nevis.

Etymology: From the Latin ‘ nivalis ’, snowy. In reference to ‘ Nuestra Señora de las Nieves ’, ‘Our Lady of the Snows’, the early Spanish name for Nevis, apparently so-called because of misidentification of the clouds surrounding Mount Nevis.

Description: No complete or partial skulls known; cranial morphology based on dissociated elements ( Fig. 10H–K View Figure 10 ). Nasals short, terminating anterior to or extending slightly further than the maxillary– frontal–lacrimal suture, and with blunt posterior margin. Premaxillaries extend posteriorly almost as far as nasals. Interorbital region slightly convergent anteriorly, with subtle supraorbital crests. Postorbital ridge apparently absent; frontosquamosal suture collinear with frontoparietal suture, dorsal facet of frontal not in contact with squamosal. Zygomatic plate broad, with anterodorsal margin smoothly rounded and conspicuously anterior to superior maxillary root of zygoma, and posterior margin situated slightly anterior to alveolus of M1. Posterior margin of incisive foramen terminates immediately posterior to anterior margin of alveolus of M1. Bony palate long and relatively flat, with shallow lateral excavations; mesopterygoid fossa does not extend anteriorly between maxillary bones.

Capsular process of lower incisor alveolus present in the mandible, situated either ventral to the coronoid process or between the coronoid process and the condyle process. Superior and inferior masseteric ridges often conjoined anteriorly as single crest, which terminates ventral to anterior margin of m1.

Upper incisors with smoothly rounded enamel bands. Maxillary tooth rows parallel. Molars bunodont and brachyodont, with labial flexi enclosed by a cingulum; labial and lingual flexi meet at midline, enamel overlaps. All upper molars with three roots (accessory labial root of M1 absent). m1 with two large roots and two central accessory roots, m2 with one large posterior and two smaller anterior roots, and m3 with one large anterior and one large posterior root ( Fig 10 View Figure 10 A-G).

M1 anterocone undivided and well developed (equal in length and width to protocone–paracone). Internal fold of procingulum circular, medially situated, and eliminated by heavy wear in older specimens. Anteroloph reaching labial margin, separated from anterocone by short anteroflexus, which extends to internal fold and disappears with slight wear. Protostyle absent; protoflexus broad and deep, with large, gently squared apex. Paraflexus transversely oriented from labial wall, deflected posteriorly close to crown midline, and extends along entire length of paracone. Mesoloph well developed; mesoflexus short, transverse, with slightly expanded apex. Paracone connected by enamel bridge to anterior or middle moiety of protocone; median mure connected to protocone. Hypoflexus slightly deeper than protoflexus, with triangular apex. Metaflexus deep, crescentic, extending over halfway across crown, almost reaching posterior wall, and reaching hypoflexus. Posteroflexus small, obliquely anterolingual notch at posterior margin of metacone. Very small internal fossette situated between posteroflexus and posterolabial margin of metaflexus, sometimes discernible on worn teeth.

M2 protoflexus absent; mesoflexus present as single internal fossette; paracone without accessory loph. Paraflexus slightly posterolinguad, extending halfway across crown. Mesoflexus very reduced, defining small triangular mesoloph. Mesoflexus internal fossette usually slightly anterolinguad and anteroposteriorly constricted medially. Hypoflexus very deep, sometimes with slightly rounded, expanded apex, and anteroposteriorly shorter than on M1. Metaflexus crescentic, deep and broad, extending well over halfway across crown. Posteroflexus very small and faint, apparently apically bifurcated.

M3 with developed mesoloph, but posteroloph absent (or vestigial; joined to metacone with little wear). Hypoflexus narrow and extremely small in specimens with little wear, disappearing with moderate to heavy wear. Paraflexus slightly posterolinguad, broad and deep on unworn teeth, becoming greatly reduced by wear; can form separate small internal fold adjacent to apex. Mesoflexus large, transverse; can become isolated as an island. Paracone transverse, anteroposteriorly short or triangular; almost isolated by paraflexus and mesoflexus. Metaflexus posterolinguad, anteriorly convex, extending 75% of the distance across crown, often reaching hypoflexus region; can coalesce distally with diminutive posteroflexus to develop bifurcated apex.

m1 with enclosed anteroflexid and anteromedian fossettids crowded together, each with an anterior extension close to the crown midline; coalescing into a single transverse fossettid with minor wear. Anterolabial cingulum present, fused with anterolabial surface of protoconid. Protoflexid narrowly compressed labially, with apex bifurcated, and obliquely anterolinguad, almost reaching anterior fossettids; can become isolated internal island with moderate wear. Hypoflexid transverse broad, deep, and open, extending halfway across crown. Small ectolophid and ectostylid present. Metaflexid small, narrow, anteroposteriorly elongated or obliquely anterolinguad; becomes isolated island with slight wear, and absent with moderate wear. Metafossetid deep and open, coalesced with deep and curved mesoflexid with slight wear, to almost completely outline the metaconid. Mesolophid and mesostylid present, connected to entoconid by lingual cingulum. Small entoflexid only present on unworn teeth. Posteroflexid and posterofossetid coalesce with slight wear, and outline entoconid. Posterofossetid deep, slightly expanded anteriorly; apex deflected posteriorly. Posteroflexid relatively straight, obliquely anterolabial. Metaconid and entoconid subquadrate; protoconid and hypoconid subtriangular.

m2 with shallow protoflexid, occupying 30% of the crown width, and obliquely anterolinguad at 45°; defines shelf-like anterolabial cingulum. Hypoflexid broad and deep, but without apical bifurcation. Metaflexid small, becoming transverse island in anterolingual corner of metaconid. Mesolophid present, joined to entoconid by lingual cingulum. Mesoflexid almost completely circumscribes metaconid, very broad and deep, extending over half of the crown width, and widening gradually away from lingual wall; apex coalesced with transversely elliptical first internal fold. Posteroflexid very deep, even with slight wear; extends to midline, becoming more transverse with wear. Entoflexid slightly obliquely posterolabiad, with distinct short medial anterior extension, extends labially just beyond crown midline.

Anterolabial cingulum and protoflexid of m3 similar to condition in m2, but with protoflexid slightly more transverse and shallow. Hypoflexid prominent, occupying over half of the crown width, but anteroposteriorly shorter than in m2; gently curved, or with anterior margin curved and posterior margin straight and obliquely anterolabial at 45°. Metaflexid small, transverse island in anterolingual corner of metaconid; disappears with slight wear. Mesoflexid long, deep, occupying 70% of the crown width, and curving around metaconid, with slight bifurcation at medial apex. Entoconid very small and subtriangular. Entoflexid and posteroflexid distinct only on unworn teeth, otherwise coalesced. Entoflexid 50–60% of the crown width, and 35–40% of the crown length; obliquely posterolabiad at almost 45°; with anterior extension close to lingual margin. Posteroflexid small and transverse.

Remarks: Our description of a new genus for this taxon is based on the morphological distinctiveness of the new material, both in size ( Tables 1 View Table 1 , 3 View Table 3 ) and in qualitative craniodental characters ( Table 2 View Table 2 ), and in the results of phylogenetic analyses. The corroboration of this hypothesis awaits the discovery of additional material that would allow for a more complete phylogenetic assessment.

Although preliminary analysis of zooarchaeological material from Hichmans suggested that two rice rat size morphs might be found at the site ( Nokkert, 2002), more detailed morphological and morphometric investigation indicates that only a single rice rat taxon is present ( Table 3 View Table 3 ). The slight variation in body size of some specimens (e.g. NHM M 82459; = ‘ Megalomys ’ of Nokkert, 2002) is associated with increased age and extreme tooth wear.

The islands of St. Eustatius, St. Kitts, and Nevis share a submerged bank that would have formed a single, larger island during low sea-level stands in Quaternary glacial periods ( Pregill et al., 1994; Lambeck & Chappell, 2001). They can therefore be considered as a single biogeographic unit, with only episodic barriers to gene flow between different populations of a single species. No morphological qualitative character was observed to vary between the three island samples. However, minor but statistically significant differences in maxillary and mandibular tooth-row length (interpreted as an indirect measure of overall body size) were observed between different sampled island populations of Pennatomys from the St. Kitts Bank. The Nevis sample is significantly smaller in mandibular tooth-row length than the St. Kitts sample, and is significantly smaller in maxillary tooth-row length than both the St. Kitts and St. Eustatius samples (one-way ANOVA: maxillary tooth row length, F = 11.14, P < 0.001; mandibular tooth row length, F = 5.18, P = 0.008; Table 3 View Table 3 ). This pattern may reflect genuine biological differences between the three populations, possibly associated with the ‘island rule’ (terrestrial vertebrate body mass increases with increasing island area; Burness et al., 2001), as St. Kitts ( 174.2 km 2) is approximately twice the size of Nevis ( 92.5 km 2). However, this pattern is not straightforward, as St. Eustatius, the smallest of the three islands ( 21 km 2), contains rice rats that do not differ significantly in body size from the St. Kitts population by either tooth-row measurement. As all examined material was retrieved from archaeological middens, these observed size differences might also be explained by differential patterns of Amerindian exploitation of rice rats on different islands. This alternative hypothesis is supported by the observation that femora and humeri with completely fused epiphyses were common, and maxillary and mandibular dentition was moderately/severely worn in all rice rat specimens in the St. Kitts sample, whereas although some mature individuals were also present in samples from the other islands (see above), fused limb bones were rare or absent, and less than 50% of tooth rows exhibited strong wear in the St. Eustatius and Nevis samples, indicating that the St. Kitts sample consisted of older rice rat individuals. Longerterm temporal patterns of body size change in rice rat populations apparently driven by Amerindian overexploitation of larger individuals have also been identified on other neighbouring Lesser Antillean islands ( Nokkert, 1999; see below). Because of these difficulties in interpreting minor body size differences in otherwise morphologically uniform rice rats from sites across the St. Kitts Bank, all three island populations are interpreted here as representing the same species.

Although P. nivalis gen. et sp. nov. is an abundant component of Saladoid and post-Saladoid archaeological sites on the St. Kitts Bank, there are no confirmed records of its survival in the European historical period. The Englishman George Percy, who stopped at Nevis around 1606, reported that his men went hunting on the island and ‘got great store of Conies’ ( Wilson, 2006), but this record almost certainly refers to agoutis ( Dasyprocta View in CoL ), which had been translocated across the Windward and Leeward Islands from mainland South America by Amerindians in earlier centuries ( Newsom & Wing, 2004). Sir Henry Colt reported in 1631 that animals specifically identified as rats provided ‘good meat’ on St. Kitts ( Harlow, 1925), and in 1720 the Reverend William Smith claimed that ‘in Nevis some people do eat Rats, wrapping them up in Banano-leaves to bake them as it were under warm Embers’ ( Merrill, 1958). However, black rats ( Rattus rattus View in CoL ) have also been eaten in many parts of the West Indies during recent history ( Merrill, 1958; Higman, 2008), and these historical records may conceivably also refer to exotic murids rather than endemic rice rats. Intriguingly, there are several reports of unusual-looking rats occurring on Nevis into recent times, and being eaten by inhabitants of the island until at least the 1930s (J. Johnson, Nevis Historical and Conservation Society, pers. comm.).

| NHM |

United Kingdom, London, The Natural History Museum [formerly British Museum (Natural History)] |

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.

|

Kingdom |

|

|

Phylum |

|

|

Class |

|

|

Order |

|

|

SuperFamily |

Muroidea |

|

Family |

|

|

SubFamily |

Sigmodontinae |

|

Tribe |

Oryzomyini |

|

Genus |

Pennatomys nivalis

| Turvey, Samuel T., Weksler, Marcelo, Morris, Elaine L. & Nokkert, Mark 2010 |

P. nivalis

| Turvey & Weksler & Morris & Nokkert 2010 |

Dasyprocta

| Illiger 1811 |