Cacajao ouakary (Spix, 1823)

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6632289 |

|

DOI |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6632273 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/8477905E-8653-C342-2DD0-AF0C19A7FA7B |

|

treatment provided by |

Carolina |

|

scientific name |

Cacajao ouakary |

| status |

|

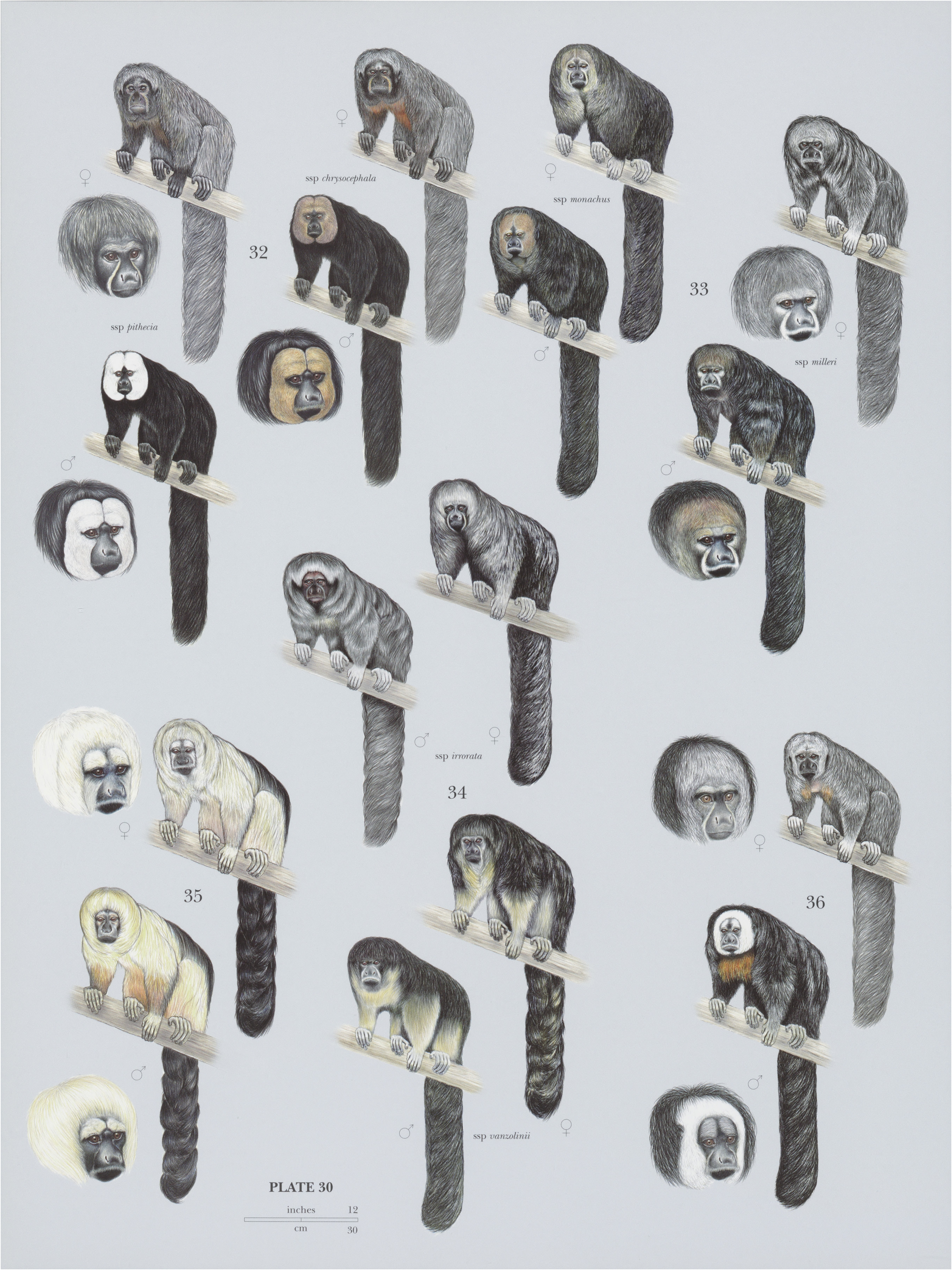

44. View Plate 30: Pitheciidae

Spix’s Black-headed Uacari

French: Ouakari de Spix / German: Spix-Schwarzkopfuakari / Spanish: Uakari de Spix

Other common names: Golden-backed Uacari/Uakari, Spix's Black-headed Uakari

Taxonomy. Brachyurus ouakary Spix, 1823 ,

Rio Ica at the confluence with the Rio Solimoes. Restricted by P. Hershkovitz in 1987 to the Rio Japura on the north bank of its confluence with the Rio Solimoes.

An alternative taxonomy was proposed by J. Boubli and coworkers in 2008. They argued that the correct name for C. ouakary (between the rios Japura-Caqueta and Negro) is C. melanocephalus and gave the black-headed uacari north of the Rio Negro a new name, C. hosomi . Here the taxonomic arrangement of P. Hershkovitz in 1987 is followed, as proposed by S. Ferrari and colleagues in 2010. Monotypic.

Distribution. S Venezuela (W of the Casiquiare), SE Colombia (from the Serrania de La Macarena in the W, E to the Guayabero-Guaviare interfluvium and the lower Rio Apaporis, and S to the Rio Caqueta), and NW Brazil (S of the Rio Negro, E to the confluence with the Rio Solimoes, and S to the Rio Japura). View Figure

Descriptive notes. Head-body 40 cm (males) and 35-56 cm (females), tail 14-15 cm (males) and 14-16 cm (females); weight 1.9-2.8 kg. Fur of Spix’s Black-headed Uacari is long and shaggy. Head, beard, nape, arms, hands, and feet are blackish. Mid-dorsum is pale orange, golden, or buffy. Lower back, thighs, and short tail are chestnut.

Habitat. Seasonally flooded forest along black-water rivers (igapo), terra firma forest, and white sand forest (“campinarana”) and scrub (“campina”). Spix’s Black-headed Uacari uses all levels of the forest strata and sometimes goes to the ground.

Food and Feeding. Spix’s Black-headed Uacariis a seed predator, with a very specialized dentition. Seeds from hard fruits can be efficiently extracted and processed by the hypertrophied canines, procumbent incisors, and low-crowned molars. In a study in Jaa National Park by A. Barnett, the diet included immature fruits and seeds (68%), mature fruits and seeds (11%), leaves and buds (9%), flowers (8%), and arthropods (4%). The most important plant families were Sapotaceae , Lecythidaceae , Fabaceae , Combretaceae , and Euphorbiaceae . Spix’s Black-headed Uacaris can forage in all strata of forest vegetation, but they prefer the canopy, where they find more fruits. When fruits are scarce in canopy trees in Jau they change their foraging level, increasing their consumption of fruits from understory trees. They sometimes pick up fruits floating in the water. Barnett observed Spix’s Black-headed Uacari going to the ground to eat germinating seeds and beetle larvae at times when fruits were scarce; this behavior was also seen by T. Defler on the lower Rio Apaporis in Colombia. There is also a single record of Spix’s Black-headed Uacaris in the upper Rio Negro raiding nests of river turtles (Podocnemis) and eating the eggs.

Breeding. Copulation of Spix’s Black-headed Uacaris is brief, lasting no more than 30 seconds. In Brazil, infants have been reported in March—-May, and in Colombia, birthing generally occurs in January-March. These periods coincide with high fruit production in the igapo.

Activity patterns. Activity budget of Spix’s Black-headed Uacaris was studied by A. Barnett in Jau National Park. His study group allocated 48-2% ofits time to feeding and foraging, 42-7% to traveling, and 5-1% to resting. Social and other activities took up 4% of the time. Spix’s Black-headed Uacaris spend less time traveling in igap6 than in terra firma, because food trees in igapo6 are clumped. When fruits are in short supply in igapo, they eat more leaves and small fruits from understory trees and travel and forage in smaller subgroups. Preference for sleeping sites seems be related to predator avoidance. In Jau, Spix’s Black-headed Uacaris prefer to sleep in tall isolated trees close to the water’s edge. On the Rio Apaporis, Colombia, they sleep in relatively exposed sites at heights of 10-15 m in flooded igap6 and in less exposedsites at heights of 25-30 m in igapo when the floods recede and also in terra firma forest.

Movements, Home range and Social organization. Spix’s Black-headed Uacaris are found mainly in igap6 but move into terra firma forest during times of fruit shortage. They live in large multimale-multifemale groups of up to 200 individuals. Larger groups split into smaller foraging groups during the day, but they come together at the end of the day to sleep. Subgroups sometimes remain apart for several days. There is a tendency for smaller subgroups when fruit availability is low and foods are in small patches. Little is known about the movements and home range of Spix’s Black-headed Uacaris. The home range of a group of 20 individuals on the Rio Apaporis was ¢.500 ha, with average daily movement of 3000 m (50-5000 m). Population densities have been estimated at 12 ind/km?along the lower Rio Apaporis and 1-4 ind/km? near Cano Pintadillo, a tributary of the Rio Apaporis.

Status and Conservation. CITES Appendix I. Classified as Least Concern on The [UCN Red List (under C. melanocephalus ). The majority of the distribution of Spix’s Blackheaded Uacari is remote and relatively undisturbed. In Colombia, it occurs in Nukak and Puinawai natural national reserves. In Brazil, they are protected in Jaa National Park and Amana State Sustainable Development Reserve.

Bibliography. Barnett (2005), Barnett & da Cunha (1991), Barnett, Borges et al. (2002), Barnett, Bowler et al. (2013), Barnett, Boyle et al. (2012), Barnett, Castilho et al. (2005), Barnett, Schiel et al. (2011), Barnett, Shaw et al. (2012), Bezerra, Barnett et al. (2011), Bezerra, Souto & Jones (2010a, 2010b, 2012), Boubli, Silva et al. (2008), Defler (1989b, 1991, 1999b, 2001, 2003c, 2004), Ferrari, Guedes et al. (2010), Fontaine (1981), Groves (2001), Hershkovitz (1987b), Mittermeier & Coimbra-Filho (1977), Norconk (2011), Setz et al. (2013), Silva et al. (2013).

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.