Arctonyx collaris, F. CUVIER, 1825

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1096-3642.2008.00416.x |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/9D202A31-FFA7-FFE7-A4FD-FF4DFD2D8652 |

|

treatment provided by |

Felipe |

|

scientific name |

Arctonyx collaris |

| status |

|

ARCTONYX COLLARIS F. CUVIER, 1825 View in CoL

Taxonomic synonymy (unique names as originally proposed): Arctonyx collaris F. Cuvier , in Geoffroy and G. Cuvier, 1825.

Arctonyx dictator Thomas, 1910 View in CoL .

Arctonyx annaeus Thomas, 1921 View in CoL .

(?) Arctonyx rostratus Matthew and Granger, 1923 .

Arctonyx collaris consul Pocock, 1940 View in CoL .

A. c. nemaeus Pocock, 1941. ( nomen nudum; lapsus for annaeus Thomas, 1921 View in CoL )

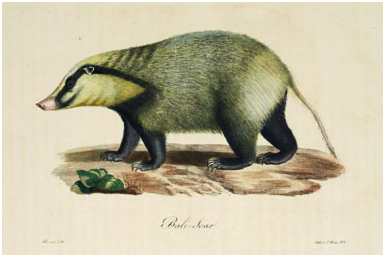

Type material and type localities: The original description of collaris was based on a figure drawn by Alfred Duvaucel of two animals (cf. Fig. 7 View Figure 7 , a composite impression that appeared in the original description) captured from hill country between Bhutan and India and exhibited in a menagerie at Barrackpore, West Bengal (Cuvier (in Geoffroy & Cuvier), 1825; Pocock, 1940, 1941). As noted above, the neotype of A collaris is AMNH 171170, an old adult male, skin and skull, from Nongpoh ( 25°54′N, 91°53′E), Khasi Hills ( Meghalaya State, India). The holotype of dictator is BMNH 1910.10.1.31, an old adult female, skin and skull, from ‘Lam-ra, Trang, Northern Malay Peninsula [= peninsular Thailand]’. The holotype of annaeus is BMNH 1910.3.10.4, an immature male, skin and skull, from ‘Nha-trang’, Annam. The holotype of rostratus is no. 18393 in the AMNH Vertebrate Paleontology collection, from ‘Yenching-kao in the vicinity of Wan-hsien’, Sichuan (middle Pleistocene). The holotype of consul is BM (NH) 1938.10.10.2, skin and skull of an adult male, from ‘Thaundaung, near [Mt] Toungoo, 4500 feet’, Myanmar ( Pocock, 1940, 1941).

Common name: We suggest the common name ‘greater hog-badger’ for this species.

Diagnosis: The most obvious distinguishing feature of Arctonyx collaris is its massive size; condylobasal length measures ± 151 mm in adults (against ³ 149 mm in A. albogularis and < 130 mm in A. hoevenii ). Indeed, A. collaris is the largest extant badger; in no other modern badger does condylobasal length exceed 150 mm. Thomas (1910: 425) aptly portrayed its tremendous size in his description of Arctonyx dictator , in which he wrote that ‘the chief feature about this Arctonyx is its enormous size, as the specimen looks like a small bear, and, though a female, exceeds any example, male or female, of A. collaris [i.e. A. albogularis ] in the [ BMNH] collection.’ Cuvier (in Geoffroy & Cuvier, 1825) was likewise impressed with its robustness, erecting the generic name Arctonyx (meaning ‘bear-claw’) based upon this species ( Palmer, 1904).

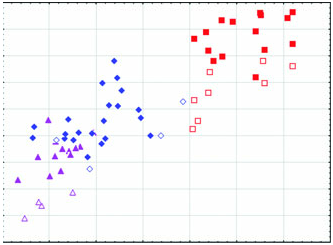

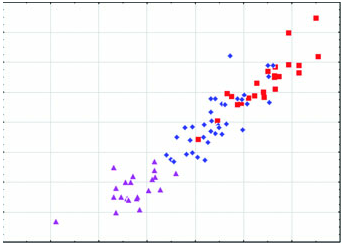

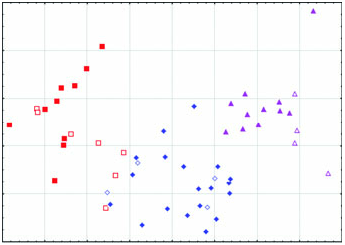

Arctonyx collaris has a massive, robustly constructed skull featuring a relatively high-domed braincase and pronounced sagittal crest, and usually a marked diastema between P2 and P 3 in both the upper and the lower jaws ( Figs 2–6 View Figure 2 View Figure 3 View Figure 4 View Figure 5 View Figure 6 , Tables 1–3). Although remarkably variable in size and shape (see below), the cheekteeth are on average considerably larger than in A. albogularis or A. hoevenii ( Fig. 3 View Figure 3 ; Tables 1–3).

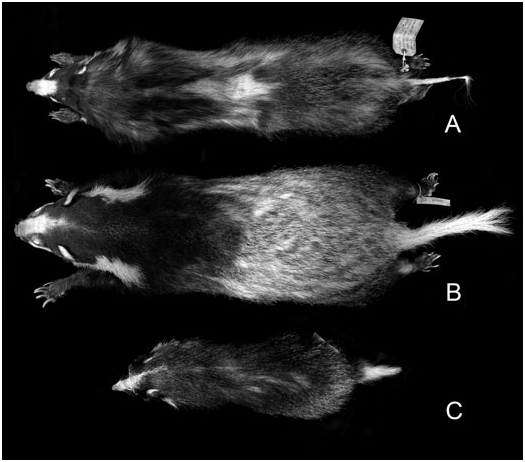

Although details of the head-striping pattern and various aspects of pelage marking are individually variable ( Osgood, 1932; Pocock, 1941), in general the forequarters are blackish, while the mid-back, hindquarters and tail are white or heavily grizzled with white, which renders the pelage typically paler than in the other Arctonyx species ( Figs 7 View Figure 7 , 9 View Figure 9 ). The pelage is characteristically shorter and coarser than in other Arctonyx . The long guard hairs of the winter coat (outer hairs measuring ³ 80 mm) overlap in length with but tend to be considerably shorter than these hairs in Arctonyx albogularis (outer hairs ± 70 mm), and the winter underfur is always much less dense than in A. albogularis . Arctonyx collaris also has a proportionally longer tail than A. albogularis or A. hoevenii , and longer and more massive claws than congeners, particularly on the forelimbs.

Distribution: Arctonyx collaris is distributed throughout the far eastern portion of the Indian Subcontinent, extending south throughout Indochina to peninsular Myanmar and Thailand ( Fig. 11 View Figure 11 ). Records from the subcontinent are from Nagaland (Naga Hills; BMNH), Meghalaya (Khasi and Jaintia Hills; AMNH, BMNH), ‘Bengal’ ( BMNH; probably ‘some locality to the east of the Ganges and Brahmaputra, possibly from Chittagong’: Pocock, 1941), Bangladesh (‘ Chittagong Hills’, BMNH; Pocock, 1941), and probably from Manipur (see Rakamantha, 1994). Arctonyx albogularis also occurs in the Indian subcontinent portion of this range. As noted above, recently published reports of Arctonyx from the Indian states of Assam ( Choudhury, 1997a), Arunachal Pradesh ( Choudhury, 1997b), North [West] Bengal ( Choudhury, 1999) and Nagaland ( Choudhury, 2000), and from extreme northern Myanmar ( Rao et al., 2005) have not been identified to species, and could represent A. albogularis , A. collaris or both species in co-occurrence (cf. Rakamantha, 1994).

All Arctonyx View in CoL specimens that we have examined from Myanmar (BMNH, MCZ, USNM), Thailand (AMNH, BMNH, MCZ, USNM), Vietnam (BMNH, MNHN), Cambodia (MNHN) and Laos (AMNH, ANSP, FMNH) represent A collaris View in CoL (for most or all distributional records and sources and associated discussion see Thomas, 1910, 1921; Osgood, 1932; Allen & Coolidge, 1940; Pocock, 1940, 1941; Urbain & Friant, 1940; van Tien, 1966; Van Peenen, 1969; Deuve, 1972; Rabinowitz, 1990; Rabinowitz & Walker, 1991; Rozhnov, 1994a, 1994b; Bergmans, 1995; Duckworth, 1997, 1998; Duckworth, Salter & Khounboline, 1999).

The southernmost distributional extent of A. collaris View in CoL lies in the far north of the Malay Peninsula, in peninsular Thailand. There is an unverified record from the Malaysian state of Upper Perak ( Tate, 1947; Medway, 1978), but no vouchered specimens originate from Malaysia and it appears to be absent from most (if not all) of that country. The westernmost occurrence of A. collaris View in CoL is probably defined by the Brahmaptura and Ganges drainages (see above). The exact northern boundary of occurrence of A. collaris View in CoL remains to be established, but may lie in Yunnan. Apart from two skins from Lichiang, Yunnan, which we provisionally identify as A. collaris View in CoL (see above, under A. albogularis View in CoL ), all specimens from China that we have seen (AMNH, FMNH, MCZ, MNHN, USNM) represent A. albogularis View in CoL . The absolute, striking distinctions in size, pelage and qualitative cranial morphology between available adult samples of A. albogularis View in CoL and A. collaris View in CoL indicate no intergradation between these taxa (cf. Pocock, 1941).

Most museum records of A. collaris from India and Myanmar with associated elevational data derive from between 700 and 1500 m (BMNH). Similarly, most museum specimens from Thailand, Vietnam and Laos with associated elevational data derive from localities situated between 600 and 1300 m. There are only a handful of specimens of A. collaris in museums marked with elevations below 600 m; the lowest elevation given on a specimen label is ‘100 m’ (BMNH 15.12.1.8, Sai Yoke, Thailand). Duckworth (1997) noted that ‘all recent records [of Arctonyx in Laos] came from above 500 m, but as all were in the same catchment, it is unclear if this represents a pattern of altitude, geography, or even just chance... All records were from forest, and elsewhere it occurs mainly in forest’ (see also Duckworth, 1998; Duckworth et al., 1999). Long & Minh (2006) discussed recent records of A. collaris in central Vietnam (the Central Annamites area), where it was encountered in ‘primary lower montane forest’ at 900 m at one site, and in ‘disturbed, primary hill forest’ at 640 m at another. Based on our canvas of published accounts and specimen label data, we suggest that the seemingly patchy occurrence of A. collaris in Southeast Asia ( Duckworth et al., 1999; Long & Minh, 2006) reflects its typical absence from lower-elevation habitats and preferred occurrence in little-disturbed hill and lower montane forests above about 500– 600 m. Undisturbed upland forested tracts possibly offer the best combination of sites for burrowing, diversity of food and escape from predation for A. collaris . The core elevational range of this species appears to lie between about 600 and 1400 m, with all records spanning 100–1500 m, but little information is available with respect to its upper elevational limit of occurrence. In their account of the mammals of Thailand, Lekagul & McNeely (1977) quoted the upper limit of occurrence as 3500 m for ‘ A. collaris ’, but we suspect this elevational information is based on highelevation localities quoted for the genus in China or Sumatra, where species other than A. collaris are found.

Geographical variation: Aspects of geographical variation in A. collaris have been discussed by Thomas (1921), Osgood (1932), Pocock (1940, 1941); Urbain & Friant (1940) and Lekagul & McNeely (1977), but always on the basis of little comparative material, in particular with very few adult skulls available. One notion that has been presented by previous reviewers is that Indochinese Arctonyx are smaller at more northern latitudes than in the south ( Pocock, 1941; Lekagul & McNeely, 1977), although Osgood (1932) observed that ‘specimens from southern Laos are fully as large as northern ones.’ Our larger sample of specimens from the region offers little evidence for a latitudinal size gradient. In any case, many fewer full-grown skulls are available from northern Myanmar and Thailand (e.g. BMNH, MCZ, USNM) than from more southerly localities, and many skulls are too imprecisely localized (e.g. skulls labelled ‘Siam’, ‘Vietnam’, or unlabelled from Indochina at MNHN and BMNH) to be useful in assessing geographical variation. We agree with Osgood (1932) that there is no clear basis for the subspecific discrimination of the nominal taxon annaeus , named by Thomas (1921) on the basis of an immature specimen, from ‘ A. c. dictator ’ (which we do not distinguish subspecifically from typical A. collaris ). Pocock’s (1940) description of consul as a somewhat smaller race linking ‘ A. c. dictator ’ (i.e. A. collaris ) and ‘ A. c. taxoides ’ (i.e. A. albogularis ) was prematurely conceived, in part because the majority of his specimens were immature (and see Pocock, 1941: 499). Our study of nearly all available museum material of Arctonyx identifies A. collaris as a morphologically distinctive species with no evidence for morphological intermediacy linking it to either A. albogularis or A. hoevenii ( Figs 2 View Figure 2 , 4–6 View Figure 4 View Figure 5 View Figure 6 ), and identifies no clear basis as yet for characterizing geographical variation within A. collaris at the trinomial level.

The middle Pleistocene fossil badger Arctonyx rostratus Matthew & Granger, 1923 , originally described as late Pliocene in age (see Hooijer, 1947) from Sichuan Province in China (type locality ‘Yen-chingkao in the vicinity of Wan-hsien’), differs from the modern hog-badger of Sichuan (i.e. A. albogularis ) in its larger size, heavier molars, pronounced diastema between P2 and P3, and more parallel-sided rostrum. All of these are characteristic features of A. collaris . Pei (1940) discussed an additional record of ‘ Arctonyx cf. rostratus ’ from the Pleistocene of Jiangsu Province, further to the east. In the holotype of rostratus , condylobasal length measures 148 mm – i.e. closer to samples of modern A. albogularis (range 110– 149 mm) than A. collaris ( 150–172 mm), although falling close to both (in the type the zygomatic arches are broken and missing, such that the skull cannot be plotted in our Fig. 2 View Figure 2 ). Based on its qualitative features, we suspect that rostratus is best characterized as a synonym (or perhaps chronological subspecies) of A. collaris . If this is the case, Sichuan and Jiangsu specimens referred to rostratus indicate that the geographical range of A. collaris extended further north in the middle Pleistocene than today. However, we suggest that it is inadvisable to synonymize this fossil taxon formally before its morphometric and qualitative features are more conclusively compared against both A. collaris and A. albogularis . More recently, Long, de Vos & Ciochon (1994) referred Middle–Late Pleistocene material of A. collaris from six different cave sites in Indochina and Thailand to ‘ A. cf. rostratus ’.

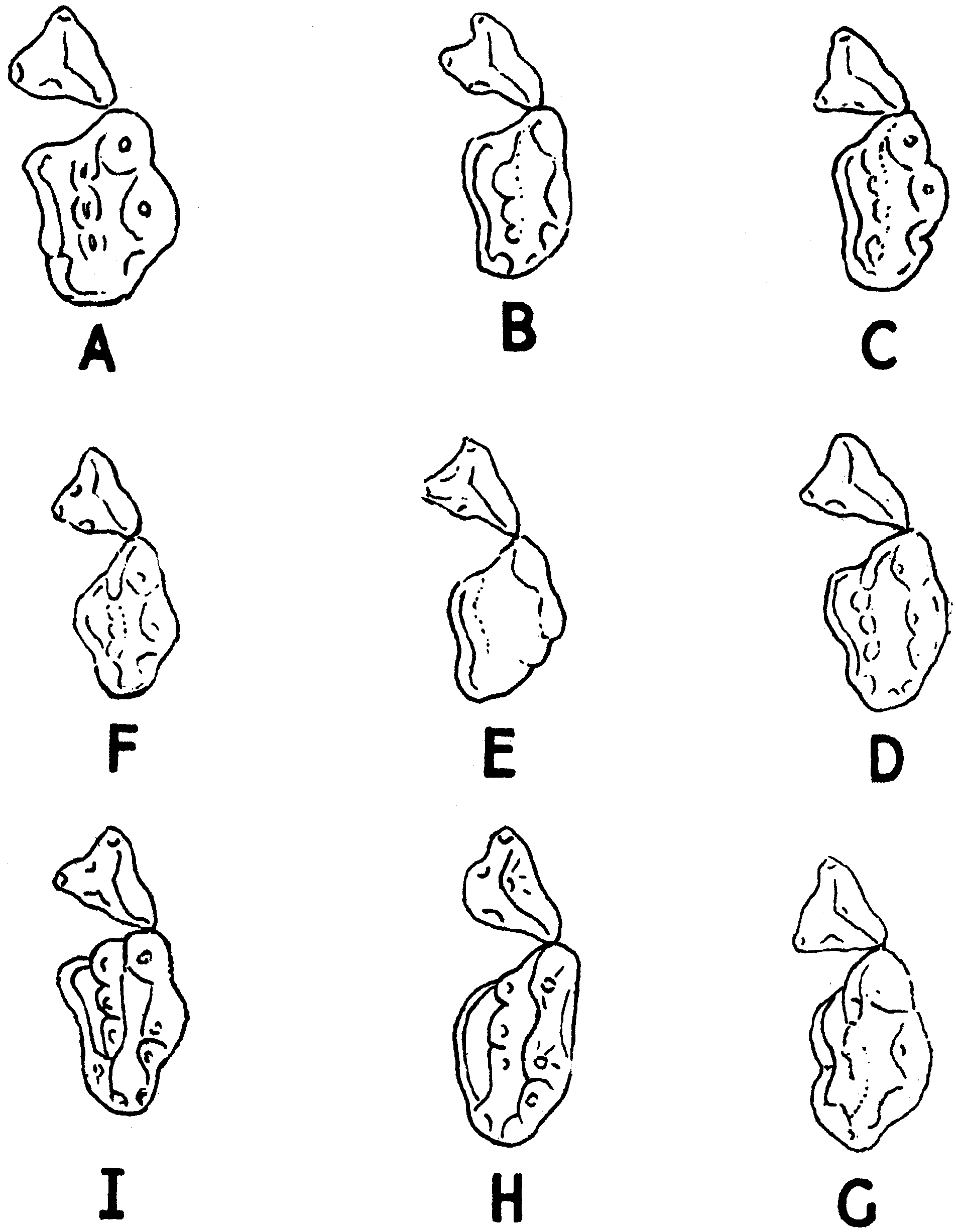

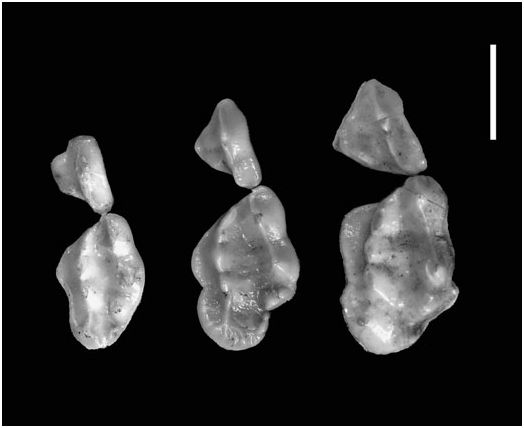

Pocock (1941) aptly illustrated the extreme variation in cheektooth size, shape and occlusal morphology within a local population of A. collaris from Mt Toungoo in Myanmar (e.g. Fig. 12 View Figure 12 ). Similarly striking is the range of dental size variation seen locally on the Bolovens Plateau of Laos and in peninsular Thailand (e.g. Figs 12 View Figure 12 , 13 View Figure 13 ). Based on our museum studies of carnivores worldwide, we suspect that A. collaris shows more intrapopulational variation in molar size than any other carnivore species ( Pocock, 1940), although molar variability is also striking in local series of Arctonyx hoevenii . This is an excellent avenue for further, detailed comparative ecomorphological study. We suggest that extraordinary cheektooth variability in Arctonyx may be tied to the greater comparative importance of vermivory in its diet relative to other badgers (see below). Committed vermivory in mammals is commonly correlated with evolutionary reduction or loss of molars and/or unusual molar size and shape variability (e.g. Griffiths, 1978; Rickart, Heaney & Utzurrum, 1991; Balete et al., 2007), assumedly reflecting the reduced importance of stringent genetic control in molar development in mammalian vermivores. Vermivory (and myrmecophagy) are also usually accompanied by a comparative elongation of the rostrum relative to related taxa ( Anderson & Jones, 1967; Griffiths, 1978; Musser, 1982), as seen in Arctonyx relative to other badgers – assumedly an adaptation for digging through the soil with the snout.

Natural history: Arctonyx collaris is found only in Southeast Asia, where it predominantly occurs in little-disturbed hill and lower montane forests. Entirely terrestrial, it sleeps in ‘burrows they dig for themselves or in convenient natural shelters, like rock-crevices’ ( Pocock, 1941: 447). Pocock (1941: 447) characterized A. collaris as nocturnal, but Duckworth et al. (1999: 188) considered it to be diurnal. Like A. hoevenii of montane Sumatra (see below), A. collaris is probably instead best characterized as cathemeral (i.e. active sporadically in accordance with its needs, without being commitedly nocturnal or diurnal; e.g. Curtis & Rasmussen, 2006; Hill, 2006; Tattersall, 2006).

Arctonyx collaris View in CoL apparently has poor eyesight, but is large, powerful and ferocious, and perhaps as a result it apparently is relatively unwary for a wild animal of its size ( Pocock, 1941). It can be approached closely and killed by men and dogs ( Pocock, 1941; Duckworth et al., 1999) or by large predators, such as cats. Rabinowitz (1990) and Rabinowitz & Walker (1991) found that A. collaris View in CoL was a common animal in Huai Kha Khaeng Wildlife Sanctuary in Thailand, noting that ‘it was sighted on several occasions and its remains were frequently found in carnivore faeces’ ( Rabinowitz & Walker, 1991). Identifiable remains of Arctonyx View in CoL were found in 5% of large carnivore scats found at one site in the sanctuary.

Very little is recorded of the diet of A. collaris View in CoL . Most available information was summarized by Pocock (1941) in his account of ‘ Arctonyx collaris consul View in CoL ’, but unfortunately this is based almost entirely on observations of animals in captivity. Observations of five animals are available ( Pocock, 1941: 447). Pocock (1941: 447) noted that the two animals on which Cuvier’s original description of A. collaris View in CoL is based ‘would eat meat, but preferred fruit, bread and milk.’ An adult male A. collaris View in CoL captured in Moulmein ( Myanmar) ‘ate voraciously meat, entrails, snakes and other reptiles, fish, and plantains, but was fondest of earthworms, which it greedily devoured as fast as they could be dug up.’ Another animal from Arakan ( Myanmar), not identified with respect to sex or age, ‘refused to eat meat or flesh of any kind, but would take bread and milk, and was particularly partial to plantains.’ A cub from Tura in the Garo Hills, first described by Jackson (1918) (which, however, may have been either A. albogularis View in CoL or A. collaris View in CoL ), fed on:

rice and rice-water, which it ate noisily, like a pig, holding the bowl between its paws. Later it had two large tins of earthworms daily, showing the same liking for them [as the Moulmein animal]... as well as bread and milk and pudding. It also ate centipedes and the contents presumably of reptiles’ eggs, rejecting the ‘leathery’ shells, but [unlike the Moulmein animal]... it was afraid of snakes and would not touch roots, fruits, or vegetables ( Pocock, 1941: 447).

In their book on Thai mammals, Lekagul & McNeely (1977) noted that Arctonyx feeds on ‘tubers, roots, earthworms, insects, and other small living creatures’, but the source of this information was not noted. Perhaps the best that can be said in summary is that A. collaris is omnivorous, and may at least partially specialize on eating earthworms.

Thomas (1910), quoting H. C. Robinson, noted that this species was known by the native name Sabima in peninsular Thailand in the early 20th century. Cuvier (in Geoffroy & Cuvier, 1825) gave the local name of this species as Bali-Saur or Bali-Soar in eastern India (apparently meaning ‘sand-pig’ or ‘bear-pig’ in Hindi). Pocock (1941: 427) provided a number of local names for Arctonyx in eastern India and Myanmar, but it is unclear whether these listed names reference A. collaris , A. albogularis or both species.

| AMNH |

American Museum of Natural History |

| BM |

Bristol Museum |

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.

|

Kingdom |

|

|

Phylum |

|

|

Class |

|

|

Order |

|

|

Family |

|

|

Genus |

Arctonyx collaris

| Helgen, Kristofer M., Lim, Norman T-L. & Helgen, Lauren E. 2008 |

Arctonyx collaris consul

| Pocock 1940 |

Arctonyx collaris consul

| Pocock 1940 |

Arctonyx rostratus

| Matthew and Granger 1923 |

Arctonyx annaeus

| Thomas 1921 |

annaeus

| Thomas 1921 |

Arctonyx dictator

| Thomas 1910 |

Arctonyx

| F. CUVIER 1825 |

A collaris

| F. Cuvier 1825 |

A. collaris

| F. Cuvier 1825 |

A. collaris

| F. Cuvier 1825 |

A. collaris

| F. Cuvier 1825 |

A. collaris

| F. Cuvier 1825 |

A. collaris

| F. Cuvier 1825 |

Arctonyx collaris

| F. Cuvier 1825 |

A. collaris

| F. Cuvier 1825 |

Arctonyx

| F. CUVIER 1825 |

A. collaris

| F. Cuvier 1825 |

A. collaris

| F. Cuvier 1825 |

A. collaris

| F. Cuvier 1825 |

A. collaris

| F. Cuvier 1825 |