Aspanlestes aptap, Nesov, 1985

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1096-3642.2011.00771.x |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/AB4D878F-FFB6-6112-529D-FCD3C74EFE81 |

|

treatment provided by |

Marcus |

|

scientific name |

Aspanlestes aptap |

| status |

|

ASPANLESTES APTAP Nesov, 1985 A

FIGURES 1–10 View Figure 1 View Figure 2 View Figure 3 View Figure 4 View Figure 5 View Figure 6 View Figure 7 View Figure 8 View Figure 9 View Figure 10

(See Appendix 4 for synonymies, referred illustrations, and referred specimens.)

Holotype: CCMGE 4 View Materials /12176, right dentary fragment with p4-5, m1-2 and alveoli for p2-3.

Type locality and horizon: CDZH-17a, Dzharakuduk, Kyzylkum Desert, Uzbekistan. Bissekty Formation, Upper Cretaceous (middle- upper Turonian).

Revised diagnosis: Differs from Zhelestes by P3 doublerooted; mandibular condyle positioned at or slightly above alveolar level; p5 paraconid is trigonid cusp rather than part of cingulum. Differs from Zhelestes and Eoungulatum by upper and lower canine double-rooted. Differs from Parazhelestes and Eoungulatum by P1 single-rooted; protocone labial shift absent. Differs from Eoungulatum by P5 protocone smaller, lower than paracone; P5 metacone swelling small; upper molars metacone slightly smaller than paracone; ‘coronoid’ facet absent; masseteric fossa bordered ventrally by welldefined crest connected to condyle. Differs from Parazhelestes by trigonid angle between 36–49°.

Description: Skull. Fragments of a skull were recovered in 2003 from CBI-14. These consisted of most of the frontal, much of the presphenoid, much of the basisphenoid, the left pars cochlearis of the petrosal, the pars cochlearis and pars canalicularis of the right petrosal, the right exoccipital, and the right maxillary fragment with M2 and alveoli for M1 and M3. Although no fragments were in direct contact with each other, they almost certainly belong to the same individual based on the similarity of preservation and

5 mm

because they were the only mammalian cranial remains from a particular bag of screen washing concentrate. Additionally, the pars cochlearis and pars canalicularis of the right petrosal and the right exoccipital fit well together, and the presphenoid and basisphenoid slightly less so. All cranial remains were given the same number, URBAC 03–93, except for the right maxillary fragment, which was given the number URBAC 03–188 because of a slight doubt that it was from the same individual. All fragments, including the maxilla, are of the correct, smaller size to be assignable to Aspanlestes aptap , the smallest of the Dzharakuduk zhelestids. Further, the two damaged petrosals accord well with the smallest petrosals described elsewhere for zhelestids ( Ekdale et al., 2004) and are probably referable to Aspanlestes .

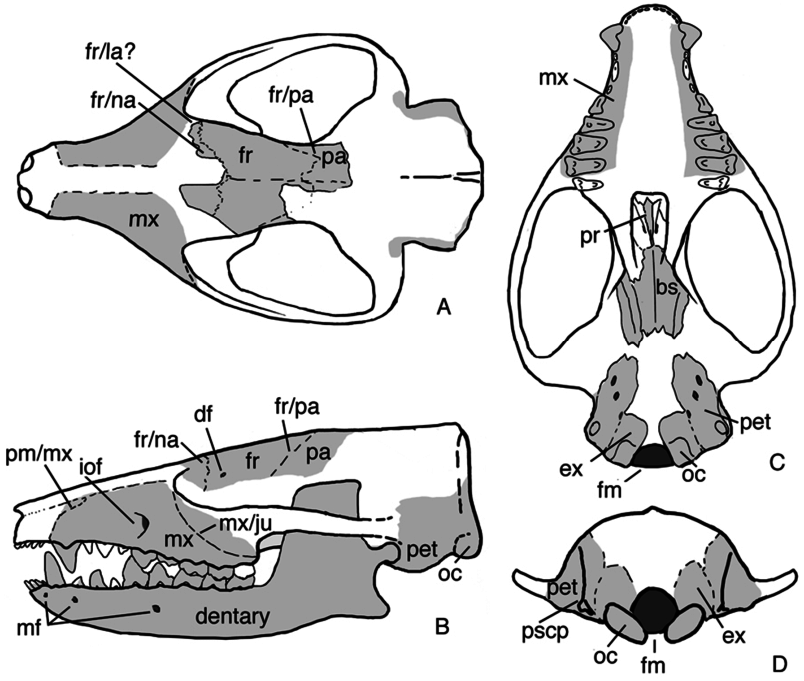

Each of the bones is described below in more detail as well as being figured. Here, we describe and compare broadly our reconstruction of the skull relative to other Asian ( Mongolia and Uzbekistan) Cretaceous eutherians ( Fig. 1 View Figure 1 ). For comparison we use the reconstructions of Wible, Novacek & Rougier (2004: fig. 51), Wible et al. (2009: fig. 35) of the zalambdalestids Kulbeckia , Barunlestes , and Zalambdalestes , as well as the asioryctitheres Kennalestes , Asioryctes , and Daulestes , and the cimolestan Maelestes . Identifications of anatomical features extensively used the following sources: Crouch, 1969; Wible 1990, 2003, 2008; Ekdale et al. 2004; Wible et al. 2004, 2009; Mead & Fordyce 2009.

Although much of the skull is unknown, what is preserved provides some limits on the proportions of the skull and dentary. In overall size, the skull was probably some 5 mm longer than skulls of both Barunlestes and Kulbeckia , but almost 10 mm shorter than Zalambdalestes . Recall that Aspanlestes is the smallest Dzharakuduk zhelestid, so the largest taxon, Eoungulatum would probably have exceeded the length of Zalambdalestes . Relative to the zalambdalestids and the asioryctitheres, Aspanlestes , and almost certainly other Dzharakuduk zhelestids, were built somewhat more robustly. The preorbital region was wider and shorter, and probably deeper compared to these other taxa. The snout was definitely less laterally constricted than in zalambdalestids and possibly also than in asioryctitheres. As the premaxillary region is unknown we do not know the anatomy of this region, but the dentary probably extended nearly as far anteriorly as the premaxilla. This slightly greater robustness continues in the dentary, notably in the depth, which is similar to that in Barunlestes . The ascending ramus of the dentary, and most especially of the dorsal part of the mandibular condyle, is quite large and rectangular in outline. This most resembles Asioryctes although the flat, dorsal margin of the ascending ramus is probably longer in Aspanlestes .

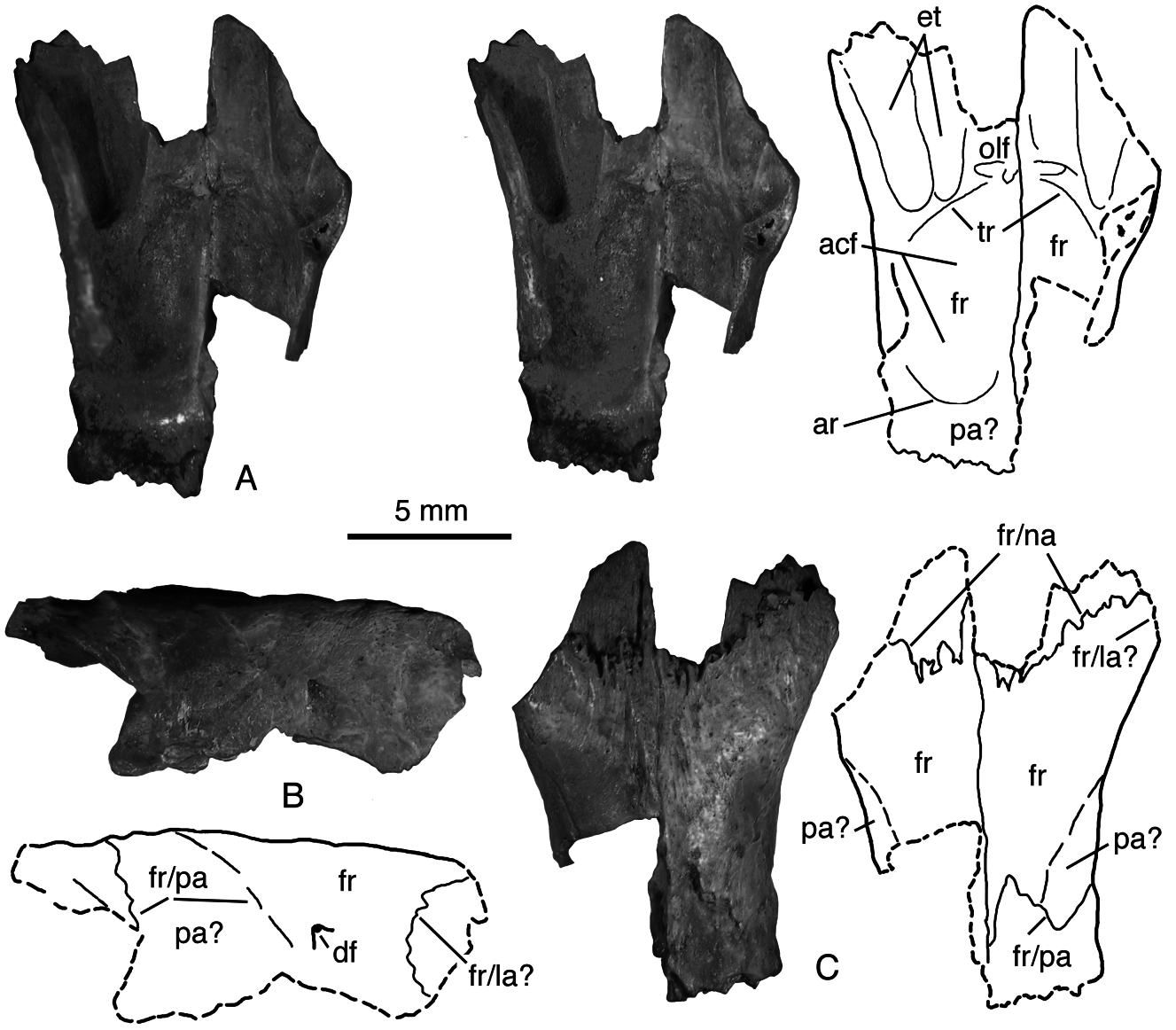

Frontal and parietal(?). Much of both frontals are preserved ( Fig. 2 View Figure 2 ). There is considerable constriction laterally through the frontals, slightly more so than in the placental Erinaceus but less than in the marsupial Didelphis . On the dorsal surface at the anterior and posterior margins of the preserved portions of the frontals, denticulated sutures are present for the nasals (fr/na) and parietals (fr/pa), respectively. The nasals and parietals clearly formed lappets of bone overlying the frontals dorsally. The nasals were expanded at least posteriorly at their contact with the frontals. The better-preserved right frontal has a facet at its anterolateral margin that was probably for the lacrimal (fr/la?), which in turn probably contacted the right nasal. What are probably small lappets of the parietals can be seen near the posterolateral margins of both frontals (pa?). This would place the narrowest part of the cranial vault near the frontal/ parietal suture as in many smaller-brained mammals. In lateral view there is a small foramen that has no endocranial aperture. This is most likely to be the frontal diploic vein foramen (df). Intracranially (ventral), elongate semicircular depressions and ridges are present at the anterior end of the frontals and housed ethmoturbinals (et). Medially is the olfactory fossa (olf). Posteriorly a transverse ridge (tr) separates the olfactory fossa from the anterior cranial fossa (acf). This fossa is delimited posteriorly by a broad, low annular ridge (ar) between the anterior and middle cranial fossae. The parietals certainly overlaid this region dorsally as lappets of bone covering the frontals, but it cannot be determined if the parietals are also exposed internally on the preserved portion of the bone.

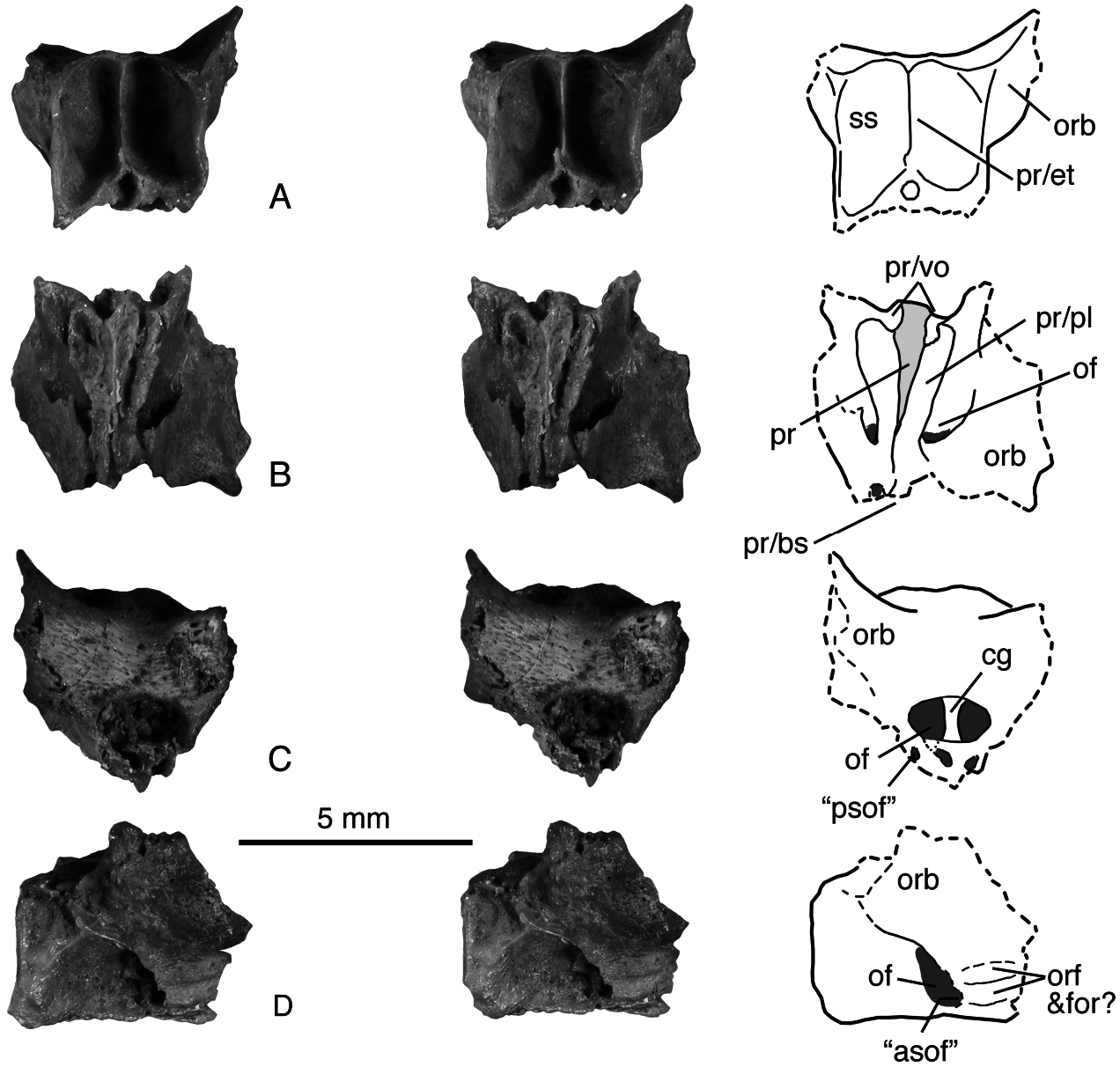

Presphenoid. Most of the body of the presphenoid (pr) and part of the orbitosphenoid wings (orb) are preserved ( Fig. 3 View Figure 3 ). Ventrally, articulation surfaces are recognizable for the basisphenoid (pr/bs), the palatines (pr/pl), and the vomer (pr/vo). In the articulated skull, the only part of the presphenoid that would have been exposed ventrally would have been a long, narrow dagger-shaped surface (light grey in Fig. 3B View Figure 3 ). The lateral sides of the orbitosphenoid wings would have been exposed in the orbital region. The floor of each large optic foramen (of) is traversed by a small canal, the function of which is not known. The anterior aperture is labelled the ‘anterior small optic foramen’ (‘asof’) and the ‘posterior small optic foramen’ (‘psof’) ( Fig. 3C, D View Figure 3 ). Two similarly sized canals (‘smf’) on the anteromedial margin of the preserved part of the basisphenoid ( Fig. 4A View Figure 4 ) may have been a continuation of these small canals. A small area of bone-to-bone contact may be preserved between the presphenoid and basisphenoid (pr/bs). There is not enough of the contact present to determine if the presphenoid and basisphenoid were fused or separate bones. Medially there is a small depression or foramen between the two posterior small optic foramina. Dorsal to these openings is a much larger oval opening, the chiasmatic groove (cg), into which the two optic foramina (of) empty intracranially. Anteriorly, the presphenoid is well preserved with a pair of deep sphenoidal sinuses (ss) and a median, vertical ridge for the ethmoid lamina (pr/et). On the betterpreserved left side, posterolateral to the optic foramen, there are two shallow depressions that formed the medial wall of the orbital fissure (orf) and possibly the medial wall of the foramen rotundum or an alisphenoid canal (for?).

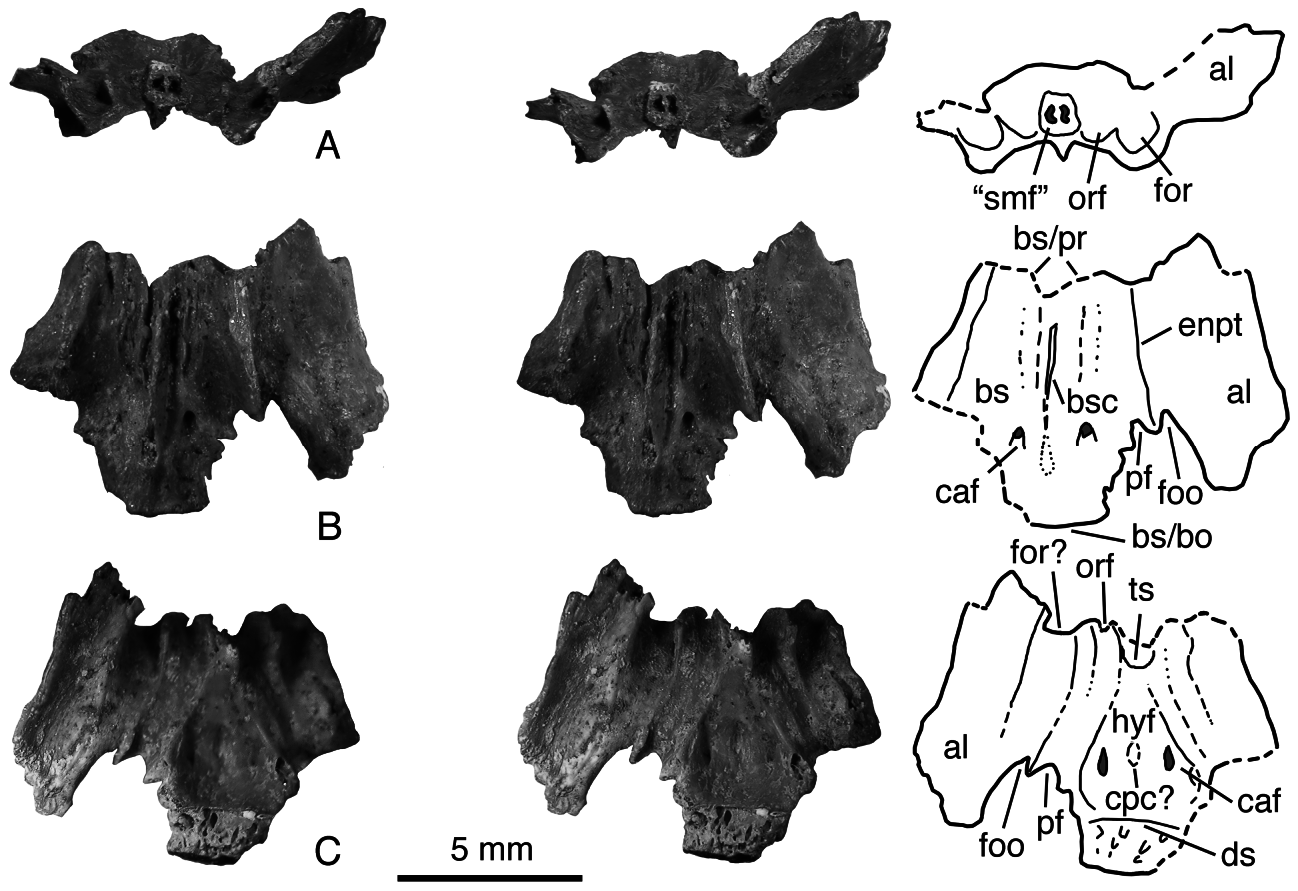

Basisphenoid. Much of the body of the basisphenoid (bs) and part of the left alisphenoid wing (al) are preserved ( Fig. 4 View Figure 4 ). Viewed anteriorly, and moving medially to laterally on each side, there are small foramina (‘smf ’), and ventrolateral margins of the orbital fissure (orf) and questionably the foramen rotundum (for?) or alisphenoid canal. The small foramina may have been confluent with the posterior small optic foramen on the posterior margin of the presphenoid. Their function is unknown. In ventral view there is a prominent midline basisphenoid crest (bsc) flanked by two crests. The bone is distinctly crenulated on either side of this medial crest. This appears to be natural rather than caused by weathering. No remnants of the pterygoid bones are discernible. The two lateral crests are possibly the broken bases of the entopterygoid processes (enpt). On the better-preserved left side, at the posterior margin where the alisphenoid and basisphenoid meet there is a finished edge with two curved surfaces that are tentatively identified as the anterior margins of the piriform fenestra (pf) and foramen ovale (foo). A carotid foramen (caf) is found on either side near the posterior extent of the basisphenoid crest. The right foramen is occluded with sediment but the left foramen opens dorsally (intracranially) into the lateral margin of the hypophyseal fossa of the sella turcica, where it continues for a short distance anteriorly as a shallow groove to the margin of the sella turcica. Anteriorly the sella turcica is bounded by the remains of a rounded, laterally narrow tuberculum sellae (ts), and posteriorly by the remains of a laterally broader dorsum sellae (ds). The intervening teardrop-shaped hypophyseal fossa is shallow but distinct. In its centre is a small fossa that may have housed a craniopharyngeal canal (cpc?).

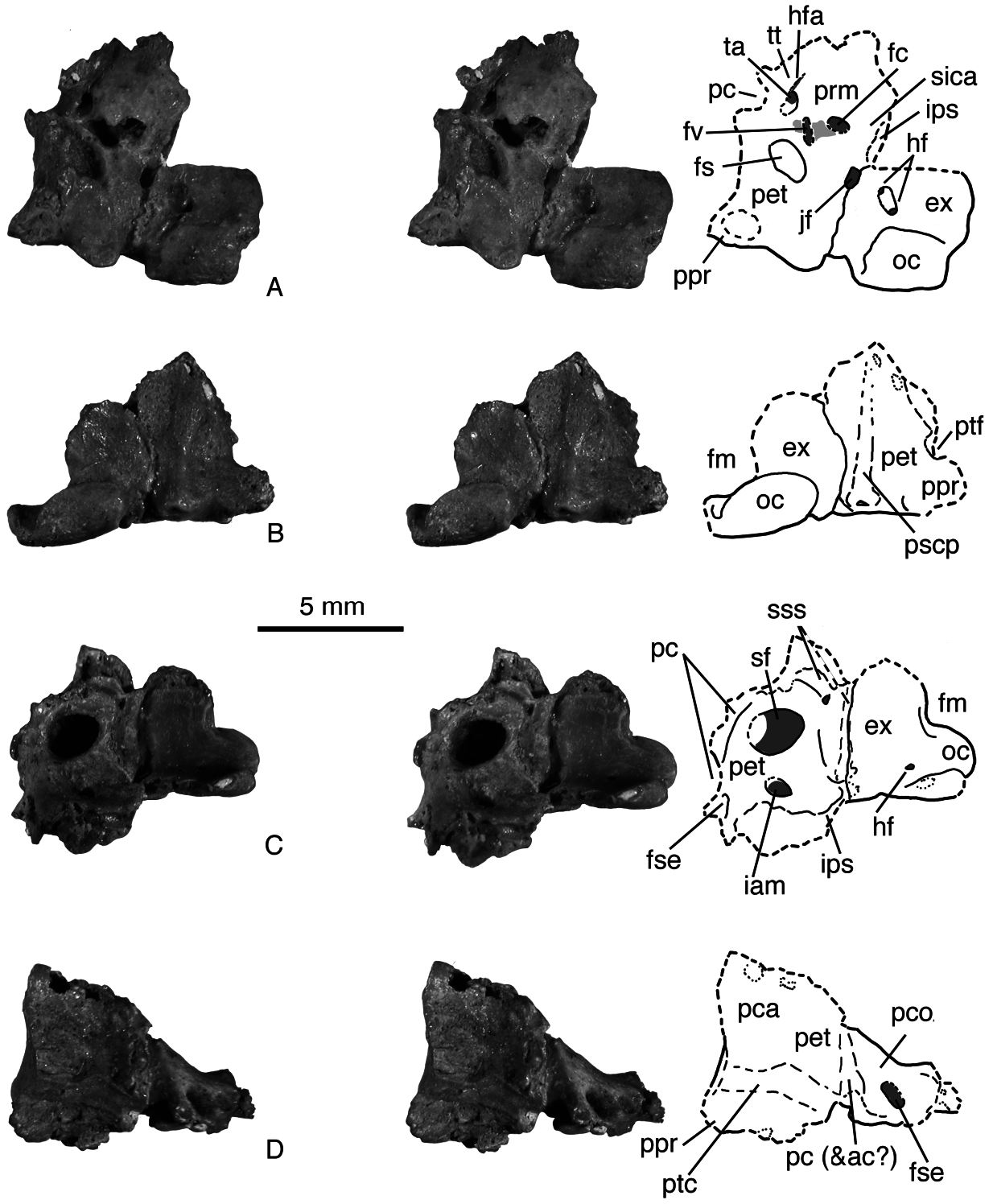

Petrosal and exoccipital. Both petrosals are preserved but the ventral surfaces of both promontoria are damaged, more so the left side. The right side is more complete in preserving both the pars cochlearis (pco) and pars canalicularis (pca). The right exoccipital (ex) is also preserved and can be articulated with the right petrosal (pet) ( Fig. 5 View Figure 5 ). It is this side that is referred to in the following description. Zhelestid petrosals have been described in detail elsewhere ( Ekdale et al., 2004) and some comparisons are made here.

The dominant aspect of the ventral part of the pars cochlearis is the ovoid-shaped and slightly bulbous promontorium (prm) that houses the cochlea of the inner ear. Although the fenestrae cochleae (fc) and vestibuli (fv) are somewhat damaged (light grey region in Fig. 5A View Figure 5 ), their original outlines can be reconstructed. The fenestra vestibuli, which receives the footplate of the stapes, had a length to width ratio of about 2 or 2.5 to 1. A similarly high ratio is common in many extant eutherians. Anterolaterally of the promontorium is the ridge-like remnant of the tegmen tympani (tt). Between the tegmen tympani and the promontorium is the tympanic aperture of the facial canal (ta). This communicates with the fenestra semilunaris (fse) on the anteromedial margin of the intracranial surface of the pars cochlearis. Running anteromedially from the facial canal is the groove of a partially covered hiatus Fallopii (hfa). Ekdale et al. (2004) noted a distinct, broad sulcus for the inferior ramus of the stapedial artery running anteriorly just lateral to the promontorium, but that there was no indication of a transpromontorial sulcus for the internal carotid artery in any of the zhelestid petrosals. The Aspanlestes petrosal described here similarly has no indication of the latter sulcus, and although there is no clear indication of the former sulcus, the shallow groove roofing the hiatus Fallopii could have held an inferior ramus of the stapedial artery. On the medial side of the promontorium is a shallow, broad depression interpreted as the sulcus for the internal carotid artery (sica). Although the petrosal and basisphenoid are not in direct contact, the identification of this sulcus is likely because just anteromedial to the sulcus there is a carotid foramen near the posterior margin of the basisphenoid described in the previous section. Posterolateral to the promontorium is a distinct, deep fossa here identified as the fossa for the stapedius muscle (fs). Ekdale et al. (2004) figured and discussed this fossa in Kulbeckia , which they termed the fossa musculus minor, but did not indicate its presence in zhelestids. They figured a zhelestid petrosal in their figure 2 (URBAC 99–41) that is at least a third larger than the petrosal here described. Although not visible in their figure because of a bony overhang of the pars canalicularis, we observed the fossa for the stapedius muscle in URBAC 99–41, although it is smaller and occurs in a more troughshaped depression rather than as distinct, deep fossa as in Aspanlestes . Using the terminology of Wible et al. (2004), the mastoid contribution to the paroccipital process (ppr) is preserved on the posterolateral margin of the pars canalicularis. The jugular foramen is found on the ventral surface near the anterior end of the petrosal/exoccipital suture. Just anterior to this a portion of the sulcus for the inferior petrosal sinus (ips) can be discerned in ventral view. On the ventral, anterolateral margin of the exoccipital is an elongate fossa that bears a hypoglossal foramen (hf) at either end. The right occipital condyle (oc) is shaped like a squat half-barrel and is visible in all views except the lateral (squamosal) view.

In posterior view, the preserved portion of the skull is quite flat with only a slight medial to lateral concavity. It is dominated by the occipital condyle and what Wible et al. (2004) termed the posterior semicircular canal prominence (pscp) on the pars canalicularis (pca). The posterior surface of the pars canalicularis was completely exposed as the mastoid exposure of the petrosal. Dorsal to the paraoccipital process (ppr) is the medial margin of the posttemporal foramen (ptf). There is not enough of the exoccipital preserved to determine whether or not it was united with the supraoccipital and basioccipital to form an occipital bone. The right margin of the foramen magnum (fm) is preserved.

The anterodorsal (intracranial) surface of the petrosal is dominated by the more posterodorsal subarcuate fossa (sf) and the more anteroventral internal auditory meatus (iam). The sulcus for the sigmoid sinus (sss) is identified dorsomedially of the subarcuate fossa. A sulcus running the vertical length of the intracranial petrosal/exoccipital suture ending ventrally at the jugular foramen is questionably identified (indicated by the dashed line in Fig. 5C View Figure 5 ) as part of the sulcus for the sigmoid sinus. Part of the quite large prootic canal (pc) is preserved dorsolaterally of the subarcuate fossa. Anteroventral to this is the opening into the cavum supracochleare referred to as the fenestra semilunaris (fse; Wible et al., 2001), which communicates with the tympanic aperture of the facial canal (ta) on the ventrolateral surface of the petrosal. In intracranial view, one hypoglossal foramen (hf) is visible in the exoccipital.

Laterally, the rugous surface of the pars canalicularis (pca) bears two shallow sulci. The post-temporal canal (ptc) horizontally traverses the length of the pars canalicularis from the posteriorly placed posttemporal foramen (ptf) to the margin of the pars canalicularis anteriorly. The absent squamosal formed the lateral wall of this sulcus as well as covering all of the lateral side of the pars canalicularis except for probably near the posteroventral margin of the paraoccipital process. Immediately anterior to the post-temporal canal is the vertically orientated continuation of the medial wall of the prootic canal. There are some unresolved differences in structure and interpretation between the zhelestid petrosals (notably URBAC 99–41) described by Ekdale et al. (2004) and the petrosal of Aspanlestes described here. On URBAC 99–41 the prootic canal is complete whereas in the Aspanlestes petrosal it is not (compare fig. 2a in Ekdale et al., 2004 with Fig. 5C View Figure 5 ). Ekdale et al. (2004) labelled a second sulcus in this region as the ascending canal of the superior ramus of the stapedial artery. No separate sulcus can be identified for this vessel in the Aspanlestes petrosal, possibly because of the damage noted above. Thus the sulcus identified on the lateral (squamosal) side as the prootic canal (pc) may have in part housed the ascending ramus (ac?).

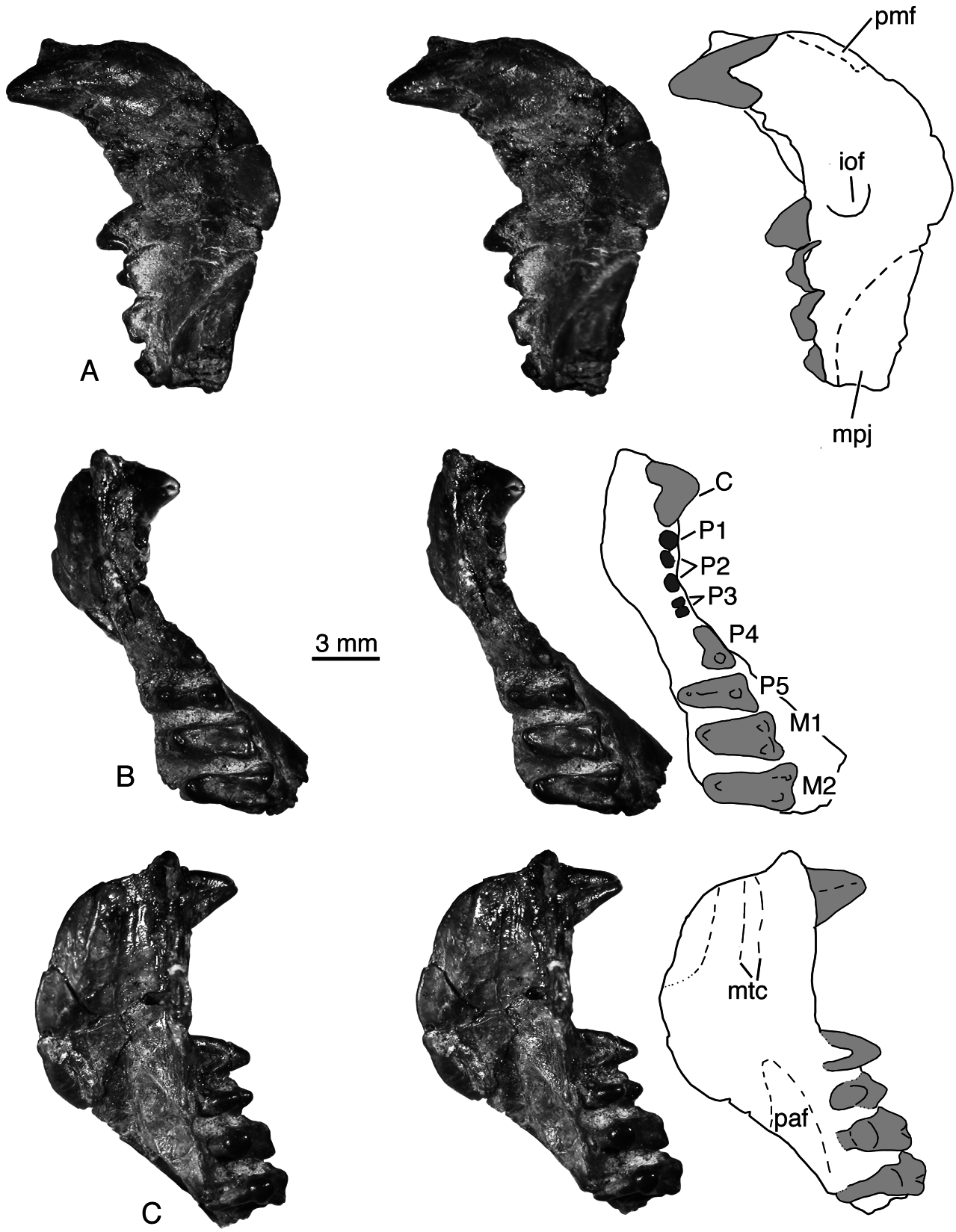

Maxilla. The best-preserved maxillary fragment is URBAC 02–45 ( Fig. 6 View Figure 6 ), with completely preserved facial and zygomatic processes, but an incomplete palatal process. The facial process is a thin, vertical plate with a convex dorsal border. It is highest above the alveoli for P2. On the lateral side at the anterior end of the facial process, above the mesial root for the upper canine, there is a short strap-like facet for the premaxilla (pmf) or possibly part of the bone is preserved. On the medial side along the anterodorsal border of the facial process there is another premaxillary facet. Approximately halfway between this facet and the palatal process there are two very faint horizontal ridges, a longer dorsal ridge and a shorter ventral ridge. These are the attachment areas for the maxilloturbinals (mtc). On the lateral surface the large oval infraorbital foramen (iof) is positioned close to the alveolar margin dorsal to the roots of P4. The zygomatic process of the maxilla extends from dorsal of P5 posteriorly to the alveolar margin of M2. Much of the maxillary process of the jugal is preserved (mpj). The maxilla- jugal contact is high above P5 but sharply descends to the alveolar margin above M2. The dorsal surface of the palatal process of maxilla is subdivided into three portions separated by two oblique ridges: the longer and smooth anterior portion is the ventral floor of the nasal cavity, the shortest middle portion of rhomboid shape possibly housed part of the maxilloturbinals, and the posterior portion sculptured by numerous pits forms the ventral floor of the orbit. The orbital floor is an anteriorly pointed triangular area bordered laterally by the zygomatic process and medially by an oblique ridge making the contact line with the palatine. The palatine facet (paf) extends anteriorly into a wedge-like pocket posterior to the maxilloturbinal area. In the anterior corner of the orbital floor there is the posterior opening of the infraorbital canal.

Jugal. As noted there is a maxillary process of the jugal laterally overlapping the zygomatic process of the maxilla in URBAC 02–45 ( Fig. 6A View Figure 6 ). It extends anteriorly to dorsal of the roots of P5. On the anterodorsal margin of the jugal- maxillary contact there is a wedge-shaped facet for the facial process of the lacrimal (not visible in Fig. 6 View Figure 6 ). The facet extends posteriorly to above the contact of M1 and M2.

Upper dentition. The upper canine is represented by an isolated specimen (ZIN 88983) and an in situ although worn specimen (URBAC 02–45; Fig. 6 View Figure 6 ). It is a large double-rooted tooth slightly larger in length than P4. The crown is low and conical, subdivided by a vertical groove on both lingual and labial sides. The mesial and distal crown halves continue dorsally forming robust and widely separated roots.

Anterior upper premolars are not known for Aspanlestes . In URBAC 02–45 ( Fig. 6 View Figure 6 ) there are five alveoli between the upper canine and P4 that are interpreted as alveoli for a single-rooted P1 and for double-rooted P2 and P3. The alveoli for P1 and P2 are approximately of the same size, whereas the alveoli for P3 are half this size. There are no diastemata between these teeth, but there is a small diastema between P3 and P4. The latter diastema is lacking in a presumably younger specimen (URBAC 00–15).

There are two specimens of P4, one of which is preserved worn but in situ ( Fig. 6 View Figure 6 ). The tooth is double-rooted with a crown somewhat longer than that of P5. The crown is conical with a large main cusp and a short distal heel. On URBAC 04–100 there is also a small mesial accessory cusp. The distal half of the crown is expanded lingually forming a protocone bulge. On URBAC 04–100 there is a lingual cingulum along the protocone bulge, as well as the distal cingulum, with a minute cuspule labial to the distal accessory cusp. The distal root of P4 is twice wider labiolingually than the mesial root ( URBAC 04–100 and the edentulous maxilla URBAC 00–15). In URBAC 04–100 the distal root is subdivided on the distal side by a vertical groove .

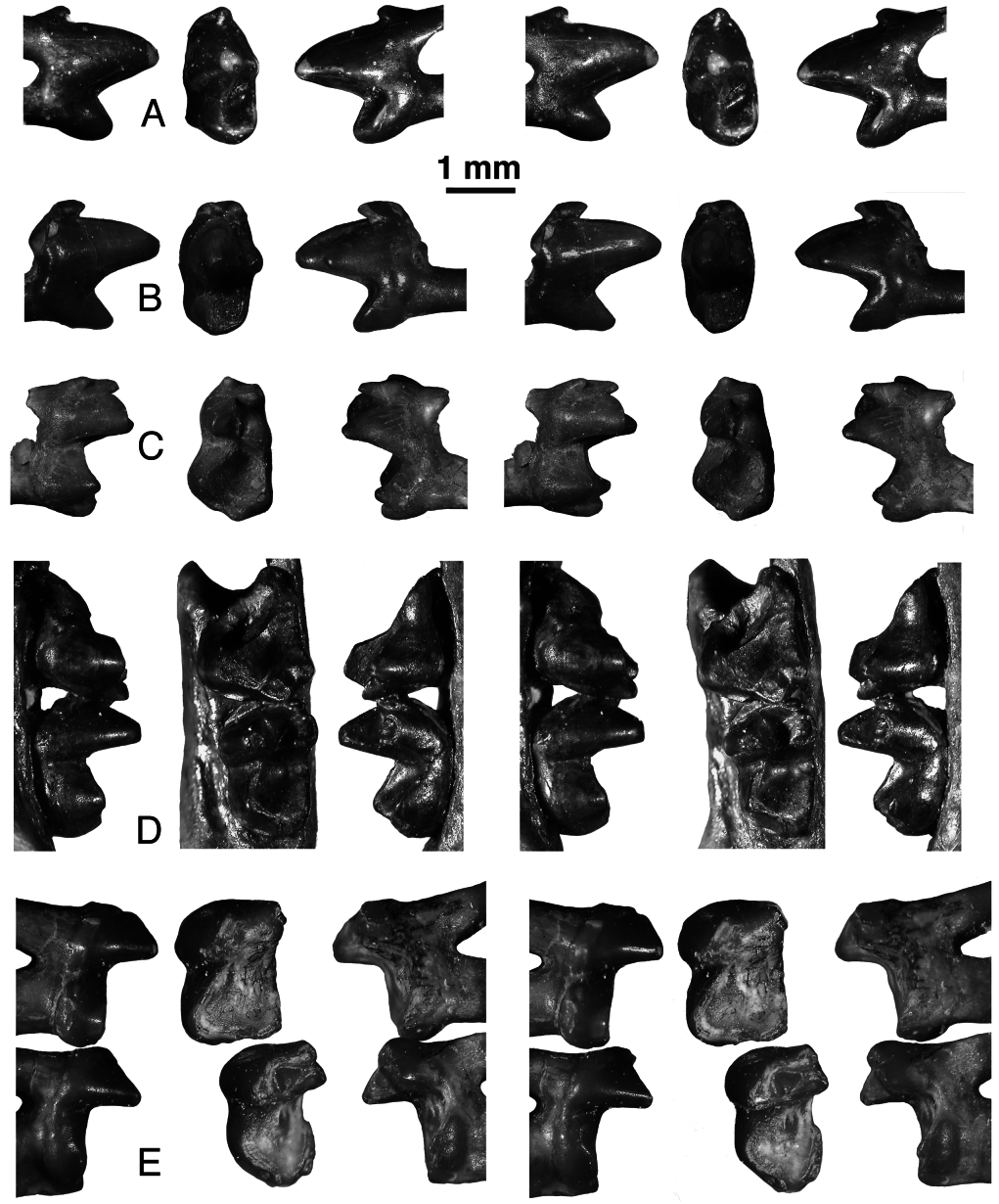

The P5 is known from several specimens, including two specimens in maxillary fragments with the molars ( Figs 6 View Figure 6 , 7 View Figure 7 ). The P5 is a submolariform tooth with a paracone, an incipient metacone, and a large protocone reaching lingually as far as the lingual margin of M1-2. The labial side is gently concave without a stylar shelf but with a narrow ectocingulum. About half of the crown is occupied by a large paracone. Anteriorly is a large parastylar lobe with a prominent parastyle. The parastyle and paracone are widely separated. The mesial side of the paracone is conical whereas the distal side is connected by a salient crest to the metastyle. On this crest there is a variably developed incipient metacone. It can be cusplike, separated by a notch from the paracone (URBAC 04–274), a swelling on the crest (most specimens), or nearly lacking (CCMGE 19/12953). The protocone is large but distinctly lower than the paracone. The shallow trigon basin is facing distoventrally and is bordered by an almost perpendicular preprotocrista and a slightly distally convex postprotocrista. In unworn specimens, such as CCMGE 1/12455 ( Fig. 7 View Figure 7 ), there is a short postparaconule and a longer preparaconule crista defining the paraconule. It is not elevated above the level of the preprotocrista. In one specimen there is a distinct ridge between the paracone and protocone and there is no paraconule ( Nesov, 1997: pl. 52, fig. 5). The preparaconule crista extends mesially towards the base of the parastyle and the postprotocrista extends distally towards the base of the metastyle. There are very faint precingulum and postcingulum at the base of the protocone. The length of these cingula varies between specimens. The P5 is three-rooted, with the smaller labial roots nearly equal in size and the lingual root much larger.

The DP5 is known from a single worn specimen ( Nesov, 1987: pl. 1, fig. 4; Nesov, Sigogneau-Russell & Russell, 1994: pl. 7, fig. 6; Nesov, 1997: pl. 48, fig. 8). The crown is triangular, with a well-developed parastylar lobe. The labial side of the crown is almost straight, with a very shallow ectoflexus. The stylar shelf is absent labial to the paracone and is very narrow labial to the metacone. On the ectocingulum there are two cusp-like crenulations labial to the paracone. The paracone is a tall, conical cusp directed somewhat mesially. The metacone (now missing) is slightly smaller and lower than the paracone. The centrocrista is a sharp, straight crest. The protocone is large but distinctly lower than the paracone. Its apex is closer to the mesial side of the crown. The conules have well-developed wings and are placed near the bases of the labial cusps; the paraconule is somewhat closer to the protocone than is the metaconule. The preparaconule and postmetaconule cristae are short and do not extend labially beyond the bases of the paracone and metacone, respectively. There are very faint, short pre- and postcingula; the latter is slightly longer. On the parastylar lobe there are a parastyle and smaller preparastyle; the latter is obscured by the wear.

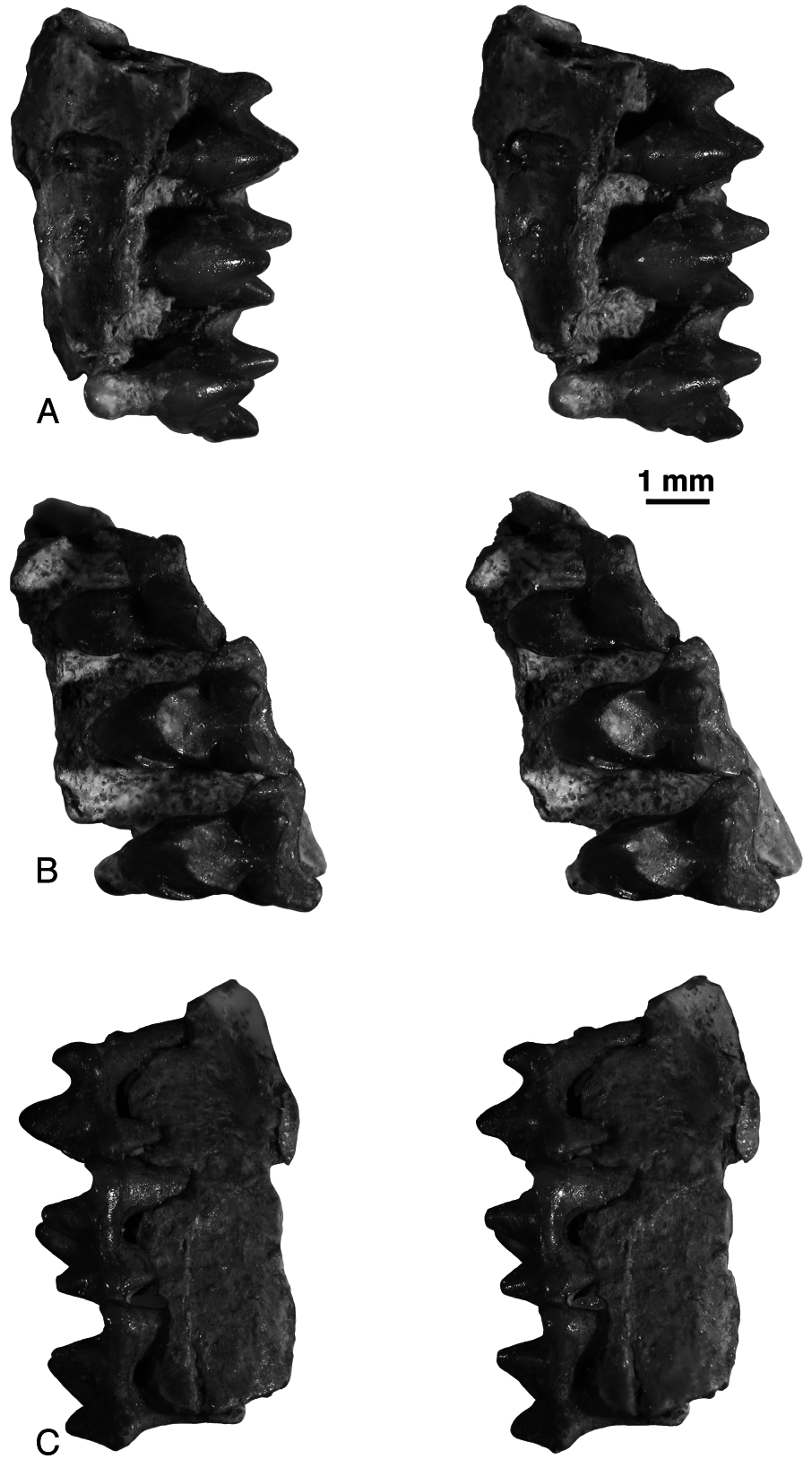

The upper molars M1-2 are known from several dentulous maxillae and isolated specimens. These teeth are quite similar in structure, differing mostly in proportions ( Figs 6–8 View Figure 6 View Figure 7 View Figure 8 ). The proportions of M1 are similar to DP5: the labial margin of the crown is nearly straight with only a slight ectoflexus. This is because the parastylar lobe is projecting mostly mesially to the paracone and the metastylar lobe is distolabial to the metacone. In M2 the ectoflexus is deeper because the parastylar lobe is projecting mesiolabially to the paracone and the metastylar lobe is mostly labial to the metacone. Also in M1 the trigon is slightly more expanded mesiodistally compared to M2. In both molars there is a distinct ectocingulum and narrow stylar shelf. Usually there are no cusps on the ectocingulum, but some M1s show inflation of the ectocingulum in the position of the stylar cusp E and in one M2 (URBAC 04–252; Fig. 8C View Figure 8 ) this cusp is well developed. In one M2 (URBAC 99–30: Fig. 8D, E View Figure 8 ) there are crenulations on the ectocingulum in positions of the stylar cusps B (stylocone), C, and E. In M1 and M2 the stylar shelf, a flat area between the ectocingulum and the bases of the labial cusps, is widest between the paracone and metacone, narrower labial to the metacone, and very narrow or almost absent labial to the paracone. The metacone is distinctly smaller than the paracone (it is relatively smaller in M2 compared with M1). The centrocrista is straight. In less worn M1s the preparacrista is directed labially towards the parastyle (URBAC 03–10, 04–126, 04–392; Fig. 8A View Figure 8 ). In worn specimens the preparacrista is gone. The preparastylar groove excavates the mesial side of the paracone and its margin could be mistaken for the preparacrista, which contacts the area of stylocone. In less worn M2s the preparacrista extends mesially towards an area between the parastyle and preparastyle (URBAC 04–252, 06–67, 06–117; Fig. 8C View Figure 8 ). The stylocone is not a distinct cusp in most M1s and M2s, except for one M1 (URBAC 04–165; Fig. 8B View Figure 8 ). On M1 and M2 the postmetacrista extends from the apex of the metacone toward the metastyle, which is usually not a distinct cusp. The trigon forms two-thirds of the crown width in M1 and M2. The protocone is large and is as tall as the metacone but lower than the paracone. Its apex is situated mesial of the centrocrista notch, in some cases almost opposite the paracone. The conules are well developed and winged, located about twice as close to the labial cusps compared to the protocone (the paraconule is a slightly closer to the protocone than is the metaconule). These conules project well above the pre- and postprotocristae. The internal conular cristae are well separated and extend labially towards the bases of their respective labial cusps. These cristae and the centrocrista border the deepest part of the trigon basin. The preparaconule crista extends labially towards the preparastyle. The paracingulum quickly becomes obliterated by wear forming part of the expanded preparastylar groove. The postmetaconule crista extends labially dorsal to the metacone apex but does not reach the metastyle. The precingulum and postcingulum are narrow but well developed (more prominent on M1 than M2). They extend labially towards the area dorsal to the conules. On the parastylar lobe there are labial parastyle and lingual, smaller preparastyle; these cusps are easily obliterated by wear and not recognizable on worn specimens.

The M3 is not known for Aspanlestes . Judging from its alveoli, best preserved in CCMGE 68/12455 [ Nesov, 1993: fig. 2(3), 1997: pl. 52, fig. 4] its lingual margin was aligned with other molars suggesting that it was not reduced in width relative to M1 and M2.

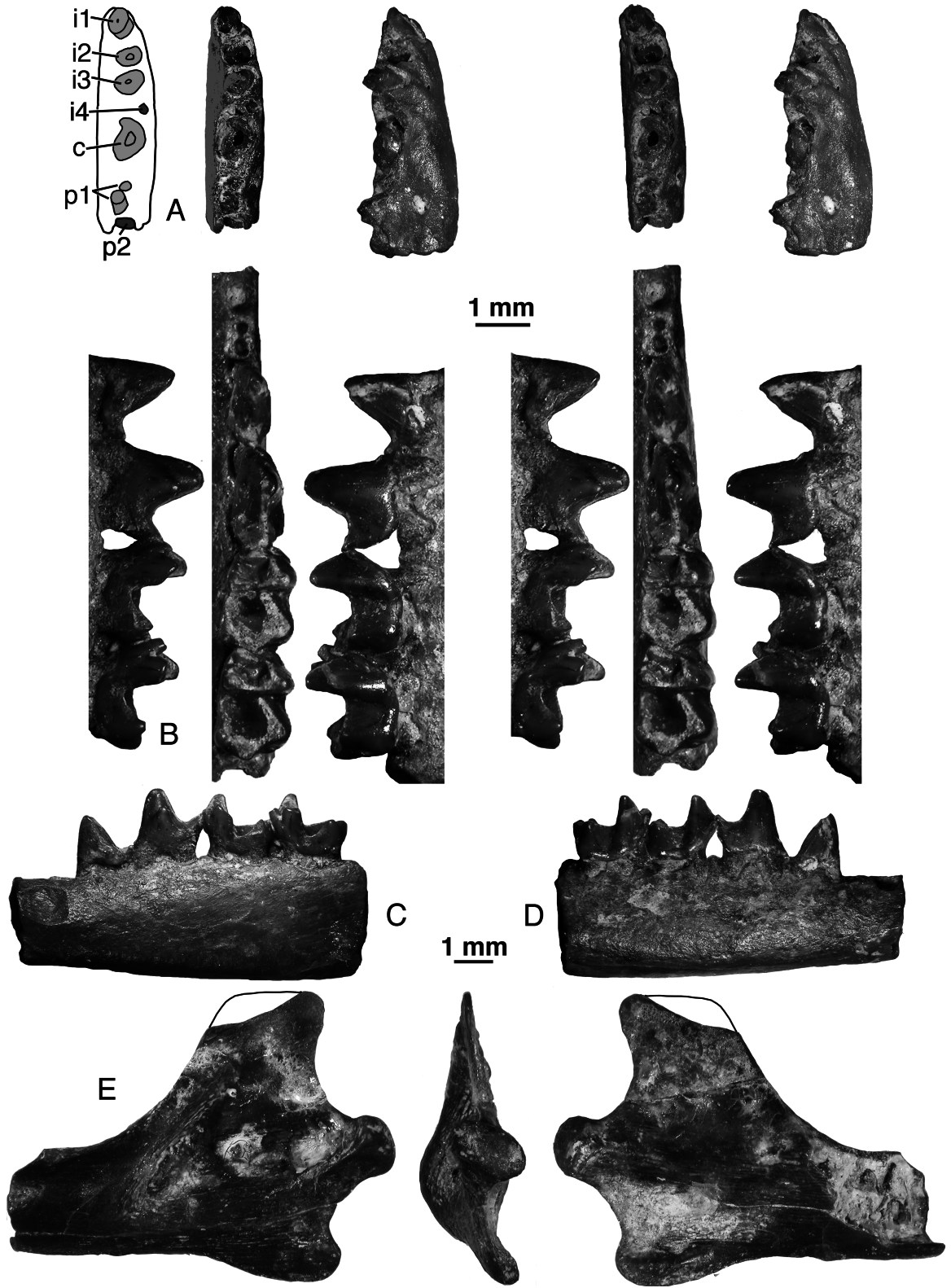

Dentary. The dentary is known from several fragments, but the anterior portion is preserved only in URBAC 04–395 ( Fig. 9A View Figure 9 ). Here the dentary is quite shallow, suggesting a juvenile or subadult. The mandibular symphysis occupies the ventral half of the entire length of the preserved fragment. A prominent horizontal ridge borders the symphysis dorsally. The alveolar border parallels this ridge in the region of canine and premolars. On the labial side there are two anterior mental foramina: a small one below i3 and another, much larger, below the mesial root of p1. The ventral border of the dentary is convex except the concavity immediately posterior to the i3.

The posterior mental foramen is between p4 and p5 ( URBAC 02–66 ), under mesial root of p5 ( ZIN 88475), or under the distal root of p5 ( holotype, CCMGE 4 View Materials /12176, Fig. 9D View Figure 9 ). The posterior end of the mandibular symphysis extends to the level of p 4 in an old individual ( ZIN 88488) in which p3 was probably lost and the alveoli filled by bone .

The ascending dentary ramus is best preserved in URBAC 02–77 ( Fig. 9E View Figure 9 ). The posterior edge is complete whereas the anterior edge is not. The horizontal ramus continues in a gentle arc on to the ascending ramus. The ascending ramus is about 2.5 times higher than the horizontal ramus, with a steep, distinct anterior border of the coronoid process, sloping at an angle of about 40° relative to the alveolar margin. The coronoid process is almost complete in URBAC 02–77, missing only a small triangular anterior piece. Accounting for the missing piece, the coronoid process is trapezoidal in form, with an almost straight anterior margin and a concave posterior margin. The masseteric fossa is very large and deep, extending posteriorly to the mandibular condyle, and bordered anteriorly by a very prominent coronoid crest. It is deepest along the ventral portion of the coronoid crest. There are two large labial mandibular foramina in most specimens. In CCMGE 69/12455 there is a single large lateral mandibular foramen that continues dorsally into a short groove. The ventral shelf of the masseteric fossa continues on to the mandibular condyle. This shelf is more prominent posteriorly than anteriorly. The medial side of the coronoid process is flat. The mandibular foramen is relatively large, oval-shaped, and facing posteriorly. It opens above the anterior portion of the angular process. On URBAC 03–31 there is a bump-like eminence in the position of the ‘coronoid facet’, which is not as developed in other specimens. Half of the mandibular condyle is above and the other half below the alveolar margin. The condyle is convex, oval in posterior and dorsal views, and at an angle of about 30° from the horizontal with the lateral end higher. The mandibular angle is a thin triangulate plate with very little medial deflection. Its anteroventral margin is convex and the posterior margin is concave, forming part of the round incisura between the mandibular angle and condyle.

Lower dentition. Lower incisors, canine, and anterior premolars are known from a single specimen referable to Aspanlestes (URBAC 04–395: Fig. 9A View Figure 9 ). It is an anterior dentary fragment with the roots of i1-3, alveolus for i4, subdivided root of c, posterior portion of p1, and mesial alveolus for p2. The i1-3 are basically similar in size, but i4, judging from the alveolus, was much smaller. The i1-3 are inclined anteriorly, with the angle of inclination decreasing from i1 to i3. The alveolus for i4 is located mesiolabial to the mesial root of the canine. The roots of the canine are subdivided by vertical grooves on both lingual and labial sides, with the distal root being more than three times larger than the mesial root, but both roots are set in a single alveolus. The worn distal portion of p1 is preserved, with a distinct distal accessory cusp. The p1 is small, with the mesial root shorter than the distal root. The p2, judging from its mesial alveolus, was distinctly larger than p1.

Judging from the alveoli in the holotype ( CCMGE 4 View Materials /12176) and ZIN 88475, p3 was double-rooted and more than twice smaller than p2 or p4. In ZIN 88488 p3 is absent probably having been lost during life with a resulting diastema between p2 and p4 .

The p4 is known only from the holotype dentary fragment ( Fig. 9B–D View Figure 9 ). The tooth is distinctly smaller than p5. The main cusp occupies most of the crown and has a strong distal crest, but no mesial crest. The mesial margin of the cusp is almost vertical. The distal half of the crown is distinctly wider than the mesial half and bears a distal heel that can be considered a distal accessory cusp. At the widest point of the crown there is a bulge-like swelling in the position of the metaconid. The distal side of the p4 crown – with a flat area between the distal crest of the main cusp, the metaconid swelling, and the distolingual cingulid – is reminiscent of the p5, although the talonid basin is more elaborated in the latter. There are no mesial accessory cusps or cingulids, except for the distal accessory cusp.

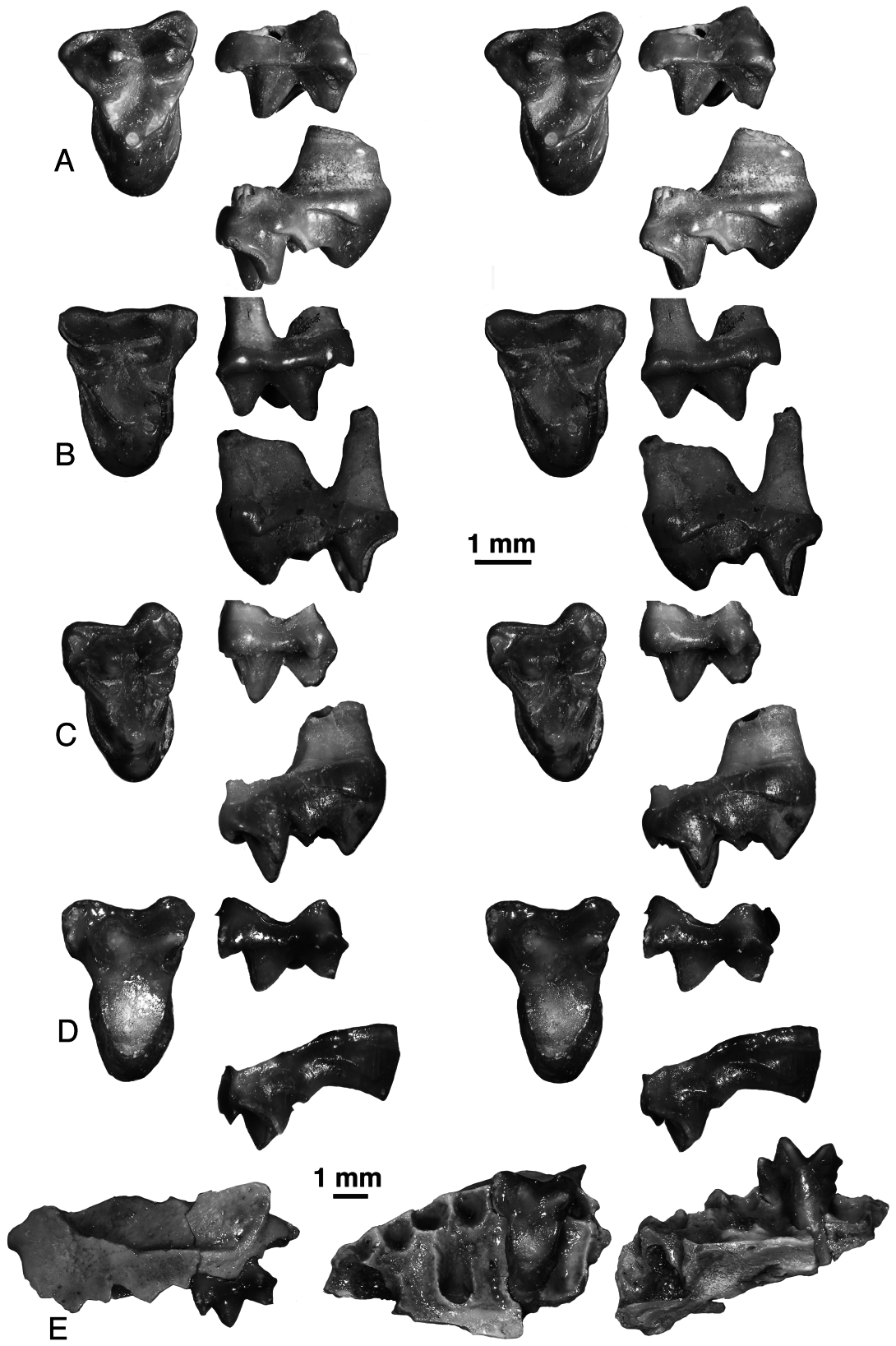

The p5 is known from two dentary fragments, including the holotype ( CCMGE 4 View Materials /12176, Fig. 9B–D View Figure 9 ), and several isolated specimens ( Fig. 10A, B View Figure 10 ). This tooth is longer than p4 and shorter than m1. The tooth is submolariform with a three-cusped trigonid and a unicuspid talonid with an incipient talonid basin. The crown morphology is quite variable. The protoconid is high and occupies the anterior two thirds of the crown. The metaconid is distinctly lower than the protoconid and variably developed: it can be just a swelling on the lingual side of the protoconid, with apices of two cusps connected by a vertical ridge ( ZIN 88473, URBAC 04–288 ; Fig. 10A View Figure 10 ), or fully separated from the protoconid by the protocristid notch ( URBAC 98–7 ; Fig. 10B View Figure 10 ). The p5 metaconid in the holotype dentary is intermediate in morphology between these variants. The development of the paraconid is highly variable: it can be totally absent ( holotype), a small cingulid cusp mesially ( URBAC 04–288 ) or mesiolingually ( URBAC 99–77 , 04–320 ) of the protoconid, or more elevated above the cingulid but still very small ( URBAC 98–7 ). On URBAC 04–288 there is a strong paracristid, a vertical ridge extending between the protoconid apex and the paraconid base. This crest is not as well developed in other specimens. There is no trigonid basin, except that in URBAC 04–288 a shallow area is delimited by the paracristid and a more lingual cristid between the bases of the paraconid and the metaconid. The talonid cusp is only slightly lower than the metaconid. The talonid basin varies in depth. It is bordered by the cristid obliqua, postcristid, and entocristid, and is confluent with the depressed area on the distal trigonid wall that is bordered by vertical ridges from the protoconid and metaconid. The lingual of these ridges (the entocristid and the metaconid ridge) are more basal in position, so the talonid basin and the depression on the distal trigonid wall are well exposed on the lingual side. In most specimens only a mesial cingulid is present, which connects lingually with the paraconid. In URBAC 99–77 there is a very faint lingual cingulid and in ZIN 88473 there is a distinct labial cingulid at the base of the talonid extending vertically towards the apex of the talonid cusp .

The dp5 is known from several isolated specimens, amongst which URBAC 97–8 ( Fig. 10C View Figure 10 ) is the most complete and unworn. Another specimen is preserved in a dentary fragment (URBAC 02–68). The trigonid angle is considerable (i.e. the trigonid basin is quite open lingually). The protoconid is distinctly higher than the metaconid, but on worn teeth the height of these cusps might be equal. The metaconid is set somewhat distal to the protoconid, resulting in an oblique position of the protocristid relative to the dentary longitudinal axis. The paraconid varies in size, but is usually much smaller than the metaconid. There is a well-developed cusp-like precingulid on the mesial side of the crown below the paracristid notch. The talonid is longer and about 1.5 times wider than the trigonid. The hypoconid is the largest talonid cusp and the hypoconulid is the smallest. The hypoconulid projects distally and is closer to the entoconid, but is not twinned with the latter. The cristid obliqua extends to below the protocristid notch. On the distal side of the hypoconid there is a faint postcingulid, extending lingually towards the hypoconulid apex.

The lower molars are known from several isolated specimens and dentulous dentary fragments. All lower molars can be easily distinguished: in m1 the trigonid angle is greater than in m2 and the paraconid is smaller and placed more labially compared with m2; in m3 the trigonid is the same as in m2 but the talonid is distinctly longer and narrower than the trigonid and the hypoconulid is more distally projecting ( Figs 9B–D View Figure 9 , 10D, E View Figure 10 ). In m1-2 the talonid is wider than the trigonid. The metaconid is only slightly lower than the protoconid. Lingually the bases of the paraconid and metaconid are separated by a variably developed groove. The trigonid basin is the largest on m2 and smallest on m3. The protocristid is transverse to the longitudinal axis of the dentary in all molars. The precingulid is well developed and is below the protoconid. All talonid cusps are well developed; the hypoconid is the largest and the entoconid the smallest. The hypoconulid occupies the most posterior position on the talonid; it is closer to the entoconid than to the hypoconid. With the wear, which removes part of the hypoconulid from the labial side, the hypoconulid appears to be even closer to the entoconid. The cristid obliqua extends to below or slightly labial to the protocristid notch. There is a short postcingulid on all molars below the hypoconid. In one m1 (CCMGE 13/12953), there is a distinct labial cingulid around the base of the protoconid between the precingulid and hypoflexid and in one m2 (URBAC 00–63) there is a short labial cingulid within the hypoflexid (ectostylid).

Measurements: See Appendices 2 and 3.

| ZIN |

Russian Academy of Sciences, Zoological Institute, Zoological Museum |

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.