Synedra berolinensis Lemmerm.

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/10.11646/phytotaxa.127.1.13 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/B30C340D-D94B-EB36-57FC-A56BFE62FAE5 |

|

treatment provided by |

Felipe |

|

scientific name |

Synedra berolinensis Lemmerm. |

| status |

|

Taxonomic history: the first 50 years

In a series of papers on planktonic algae (“Beiträge zur Kenntnis der Planktonalgen”), Ernst Lemmermann (1867–1915, for biographical data on Lemmermann see Bitter 1919) described a number of new taxa from European Lakes, some assigned to the genus Synedra ( Lemmermann 1900a; 1900b; 1904; 1906). Synedra berolinensis was one of these, first presented with just a short description and no illustrations ( Lemmermann 1900a). Lemmermann’s description is succinct enough to quote in full:

“ Zellen 25–34µ lang, zu 4–24µ zu büschelförmigen, strahligen, freischwimmenden Colonien vereinigt. Valvarseite gerade, in der Mitte etwas bauchig erweitert, an den Enden 1,3µ, in der Mitte 2, 5µ breit. Querstreifen kurz, die Mitte nicht erreichend.”

But Lemmermann did more than simply describe new taxa. He created an additional hierarchical level in the classification of Synedra by placing some species— Synedra ulna ( Nitzsch 1817: 99) Ehrenb. (1832: 87) , S. delicatissima W. Sm. (1853: 72) and S. acus Kütz. (1844: 68) —in the Section (‘Sectio’ I.) Eusynedra, and his new taxa— S. actinastroides Lemmerm. (1900a: 30) , and their varieties, and S. berolinensis —in a new section (‘Sectio’ II.), Belonastrum 1. Thus, Lemmermann determined what might be called two different ‘kinds’ (subgroups) of Synedra , captured by his division into Sections (‘Sectio’). Of significance is not just the creation of two sections but his reasons for doing so (the evidence). Lemmermann described his two sections thus:

“I. Sectio: Eunsynedra Schütt: Zellen einzeln, freischwimmend oder testsitzend” [Cells individually, free-swimming or attached]…

“II. Section: Belonastrum nob.: Zellen zur freischwimmenden, büschelförmigen, strahligen Colonien vereinigt” [Cells free-swimming, in star-shaped colonies]. ( Lemmermann 1900a: 31, my translation).

1. While Mills (1933: 265–266) lists several species in this section, it is clear that he understands Lemmermann’s taxon as a section.

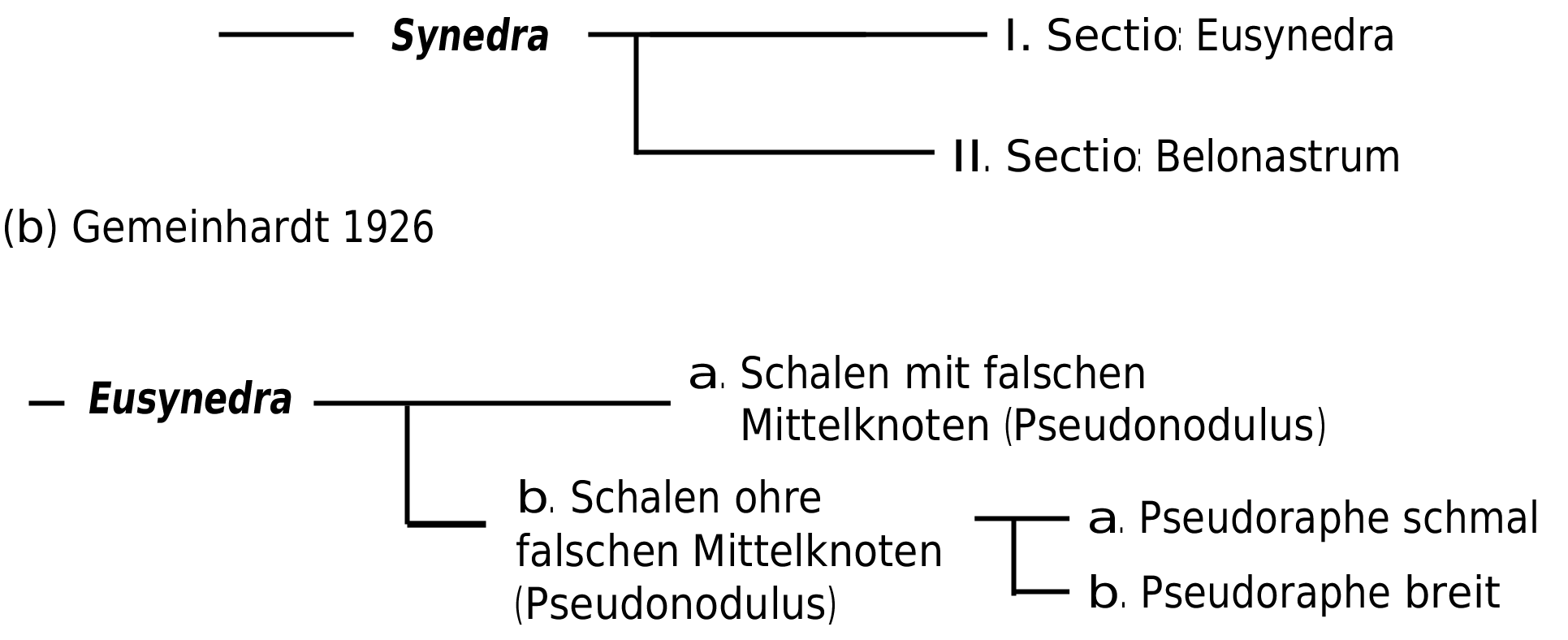

Lemmermann’s sections were thus separated on the basis of the character ‘colony formation’. That some species were found in the plankton (pelagic), an unusual (at that time) habitat for species in the genus Synedra , was the reason Lemmermann created his classification (summarised in Figure 1a View FIGURE 1 ).

(a) Lemmermann 1900a

In 1926 Konrad Gemeinhardt undertook a revision of Synedra ( Gemeinhardt 1926) . He placed Synedra berolinensis , S. actinastroides and S. limnetica Lemmerm. (1900b: 275) (all members of Lemmermann’s Section Belonastrum) in his “Pseudoraphe breit” (pseudoraphe broad) sub-group, alongside S. affinis Kütz. (1844: 68) , S. affinis f. typica Hust. (in A. Schmidt et al. 1914: pl. 304, figs 6–12), S. affinis var. obtusa Hust. (in A. Schmidt et al. 1914: pl. 304, figs 13–16) and S. affinis var. fasciculata (C. Agardh 1812: 35) Grun. in Van Heurck (1885: 153). In the “Pseudoraphe schmal” (pseudoraphe narrow) sub-group, the other half of the pair within the larger group (“Schalen ohre falschen Mittelknoten (Pseudonodulus)”—valves with ‘false’ central area, pseudonodulus)—Gemeinhardt placed S. ulna alongside species usually associated with the more ‘typical’ members of Eusynedra ( Synedra biceps Kütz. (1844: 66) , S. goulardii Bréb. (ex Cleve & Grun. 1880: 107), etc., species now understood as part of Ulnaria Kütz. , see Williams 2011). Gemeinhardt added more characters (properties of the ‘pseudoraphe’ and central area) and more (un-named) divisions and subdivisions, presenting the whole as a classification with species names appended to each sub-division ( Gemeinhardt 1926: 37, see Figure 1b View FIGURE 1 ) 2.

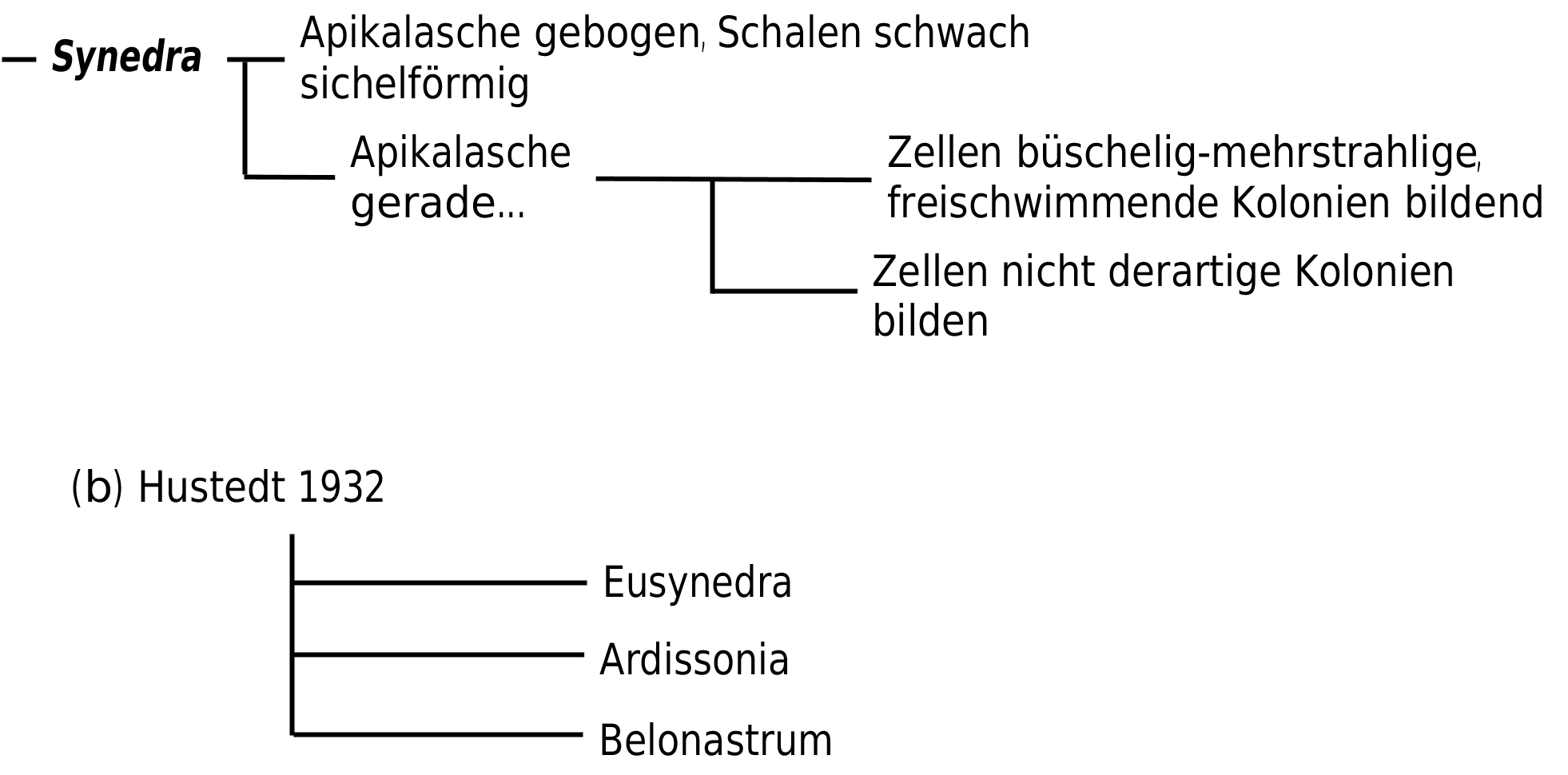

Hustedt subsequently presented two different classifications for the sub-groups of Synedra . In 1930, he offered a rather complex series of sub-divisions in the form of a key ( Hustedt 1930: 149–151). One of Hustedt’s main sub-divisions was based on ‘Apikalasche gerade…’ (apical axis straight) which in turn was sub-divided into ‘Zellen büschelig-mehrstrahlige, freischwimmende Kolonien bildend’ and ‘Zellen nicht derartige Kolonien bilden’ (similar to Lemmermann’s divisions). The former sub-group contained Synedra berolinensis , S. actinastroides and S. acus , while the latter contained all other freshwater species of Synedra ( Figure 2a View FIGURE 2 ).

Yet in 1932, Hustedt presented what might be referred to as a proper classification (as opposed to his 1930 key), in which he recognised three sub-genera, Eusynedra, Belanostrum and Ardissonia ( Figure 2b View FIGURE 2 ). By implication, none of Hustedt’s three groups is considered to be more closely related to any other (there is no hierarchical structure to the classification beyond recognising three sub-genera). Interestingly enough, of the

2. Gemeinhardt also noted the potential of cytoplasmic characters for future classification data sub-genus Belanostrum, Hustedt wrote that it “…stimmt sowohl im Bau der Zellwand als auch in der Zellform völlig mit Eusynedra überein, ein wesentlicher Unterschied besteht jedoch in der Koloniebildung…under der damit zusammenhängenden pelagischen Lebensweise” ( Hustedt 1932: 183; “Belanostrum fully agrees with Eusynedra conforming in the structure of its valves as well as its cell. However, there exists a substantial difference in colony formation which is associated with a pelagic mode of life”, translation adapted from Jensen 1985: 170 ). Therefore, Hustedt explicitly agreed with Lemmermann’s viewpoint, believing that the ‘mode of life’ is sufficient grounds for recognising a sub-group, in spite of the fact that he sees ‘full’ agreement in valve structure between Eusynedra and Belonastrum. Nevertheless, he goes on to stress that the sub-genera Belanostrum and Ardissonia “…von sehr ungleichem Wert sind” ( Hustedt 1932: 183, “are of very unequal merit [value]”, translation adapted from Jensen 1985: 170 ) without explaining the nature of that inequality.

It might be argued, with some justification, that Lemmermann, Gemeinhardt and Hustedt were simply trying to clarify how one might identify the various species thought to belong to Synedra rather than attempting to create a ‘natural’ classification (one that expresses their relationships), and their use of sections and sub-genera (as well as the many un-named subdivisions) were designed to facilitate ease of identification —as in a continually modified and updated key.

(a) Hustedt 1930

Taxonomy and light microscope (LM) images—the data

It is worth considering for a moment just what data were available for diatomists to make their judgements. Although described in 1900, no illustrations of Synedra berolinensis appeared until 1904, when Lemmermann described and named a new variety of S. berolinensis — S. berolinensis var. gracilis Lemmerm. (1904: 310) — and offered a further brief description accompanied with some simple line drawings of both Synedra berolinensis ( Lemmermann 1904: fig. 16, Fig. 3 View FIGURE 3 ) and the new variety ( Lemmermann 1904: fig. 17). Two years later, along with the description of Synedra revaliensis Lemmerm. 3, Lemmermann provided a key for all of

3. This taxon was described in two different places. The exact dates of each have yet to be established. the eight planktonic taxa he had described in the past few years that were included in his ‘Sectio’ Belonastrum ( Lemmermann 1906; see below and the first eight entries in Table 3). But even after Lemmermann’s series of papers it appears that very few illustrations of S. berolinensis were published. Hustedt (in Schmidt et al. 1914: pl. 306, figs 17, 18), for example, illustrated two partial colonies from “Holstein” (some details of the valve structure can be appreciated from his figure 18). Hustedt reproduced these illustrations in three European floras ( Hustedt 1930: 164, fig. 200; Hustedt 1932: 184, fig. 686; Hustedt 1942: 457, fig. 533, also reproduced by Cleve-Euler 1953: fig. 377a–c and Zabelina et al. 1951: 141, fig. 1a; the original images were derived from Hustedt’s contribution to Schmidt Atlas for 1914: Hustedt in A. Schmidt et al. 1914). Subsequently, Krieger (1927: figs 28a–h, j, k) presented some new illustrations, which Cleve-Euler reproduced in her flora (Cleve- Euler 1953: fig. 377d, e). In short, up until the mid-1950s even though Synedra berolinensis had been recognised for nearly half a century, it appears to have been known from only a handful of drawings, many of them being copied from one source to another as illustrations for commonly used floras.

Taxonomy and the scanning electron microscope (SEM)

One might argue that the history of Belanostrum above, and its interpretation, is now largely irrelevant, as many of the species thought to be Synedra -like (and members of the group Belanostrum) by Lemmermann have subsequently been placed elsewhere, such as in the very different genus Nitzschia Hassall , or else are now synonyms of S. berolinensis itself ( Table 3). Nevertheless, further data became available with the introduction of scanning electron microscopy.

According to Gaul et al. (1993), Cronberg (1982: Figs 164–5) provided the first SEM image of Synedra berolinensis , although two images presented in Round (1979: figs 1, 2) predate that paper by 3 years (it should be noted that Round did not name his taxon, writing in the plate legend “a species of the section Belonastrum, but not in the Synedra complex”). These were followed a few years later with three images published by Lange-Bertalot (1989). More recently, there have been two detailed studies, the first by Round & Maidana (2001) the other by Morales (2003), both authors coming to different conclusions. In spite of the new morphological data, Round & Maidana (2001) made their decision to place Synedra berolinensis in its own genus based on, among other things, its ‘habitat’ (like Hustedt earlier), while Morales (2003), after reviewing the morphological evidence, found it convincing enough to retain the species in Staurosirella (Round & Maidana did not present girdle band data but refer to their number), following Bukhityarova (1995: 418).

With respect to classification, this kind of approach has continued in diatom systematics up to the present, regardless of the source of data: the continual updating and modifying of generic descriptions, often discussed in terms of ‘limits’, as if definitions of taxa were like the borders of a country, occasionally expanding, occasionally contracting, depending on who was waging war (and who was ‘winning’) but retaining the same name to give the illusion of stability (or conquest).

When in doubt, or when presented with a number of apparently ‘key’ features, the taxon is often placed in a monotypic group. This process is akin to the construction of an artificial classification (keys) rather than natural classification, as a monotypic group, in this sense, is simply the sum of a set of unusual characters.

Current knowledge of Synedra berolinensis

Estimates of our current knowledge concerning Synedra berolinensis are hard to make and somewhat dependant on an understanding of what knowledge might mean. A rough guide can be gained from the number of citations, given that an unknown percentage of those citations might be misidentifications.

One way to ascertain citations is to use an Internet search engine where the numbers of hits may indicate a r o ug h e st i m a t e o f k no w l e dg e o r a ppl i e d k no w le dg e a tt r i bute d t o t hi s s pe c ie s. Us i ng G o o g le (www.google.com), roughly 16 to 17,000 hits were recovered, with considerably fewer using Bing (www.bing.com) (c. 50). With respect to searches for images, only two were found, relative to the 48 published drawings and light microscope images and 25 scanning electron microscope images ( Table 4). Thus, very little actually appears to be known about Synedra berolinensis although, given the 17,000 records, it appears to be well known.

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.