Martiodendron Gleason, 1935

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/ 10.11646/phytotaxa.578.1.2 |

|

DOI |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7542596 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/B43787C8-7C38-FFCF-FF50-766E41F5F7EC |

|

treatment provided by |

Plazi |

|

scientific name |

Martiodendron Gleason |

| status |

|

Martiodendron Gleason View in CoL View at ENA . Phytologia 1: 141 (1935).

Type: Martiodendron excelsum (Benth.) Gleason View in CoL

≡ Martiusia Benth. View in CoL in Hook. Journal of Botany , being a second series of the Botanical Miscellany 2: 84 (1840). nom. illeg. Type: Martiusia excelsa Benth View in CoL .

≡ Martia Benth. View in CoL in Hook. Journal of Botany , being a second series of the Botanical Miscellany 2: 146 (1840). nom. illeg. Type: Martia excelsa Benth View in CoL .

≡ Martiusa Benth. & Hook. f. Genera Plantarum 1(2): 571 (1865), orthographic variant

Shrubs to large trees, 1–50 m tall, with or without buttresses up to 5 m tall, heartwood red to orange to brown, sapwood whitish to creamy, bark smooth to wrinkled to scaly, whitish to gray to brownish, lenticellate, with transparent gelatinous exudate or without exudate; branches unarmed, the youngest slightly pubescent to glabrescent, indumentum brown to golden. Leaves imparipinnate, alternate, leaflets (3–)5–11(–13), rarely unifoliolate leaves at base of inflorescences, alternate, rarely subopposite, elliptical to ovate to oblong, apex almost always acuminate to cuspidate to acute, rarely mucronate or retuse, base truncate to obtuse to cordate to cuneate, margin entire, revolute or not, leaflets glabrescent to sparsely pubescent abaxially, glabrous adaxially, leaf rachis and petiolules glabrescent to sparsely pubescent, indumentum golden to brown; stipules deciduous, two per bud, lanceolate to elliptic to oblong; axillary and terminal buds elliptic to oblong, apex acute to acuminate to cuspidate, pubescent, indumentum golden, brown, or grey. Inflorescences thyrsoid, with distichous branching, axillary or terminal, with elongated primary and secondary axes from which distichous cymes are formed, or with short and compact cymes forming directly from the branches, sparsely to densely flowered, the axes golden- to brown-pubescent; bracts deciduous, two per triad of flowers or compound cyme and one per axil on elongated secondary axes of the thyrsoids, elliptical to lanceolate, pubescent, sometimes becoming well-developed pinnate leaves in the axils of secondary axes; pedicels cylindrical, pubescent, 4–16 mm long; bracteoles lacking. Flower buds lanceolate in outline, erect or strongly curved, apex acute to acuminate, straight or curved; flowers without hypanthium, dichlamydeous, heterochlamydeous, zygomorphic; sepals 5, free, 4 of them equal, abaxial sepal usually slightly narrower than the others, occasionally much narrower, almost valvate, imbricate only on the margins, olive to brownish to light green to yellowish, densely pubescent externally, glabrous only in the margins, sparsely pubescent to glabrescent internally, base truncate, apex acute, margin revolute, generally all sepals reflexed in anthesis, sometimes the abaxial one patent, deciduous; petals 5, free, glabrous, light yellow to golden yellow to orange, strongly to slightly unguiculate, sometimes cuneate, usually slightly uneven, the adaxial petal slightly wider than the others, apex obtuse to acuminate, deciduous, margin and surface usually wavy, region of the midrib strongly marked, prefloration strongly imbricate; stamens 4–5, antesepalous, two lateral and two adaxial stamens always present, equal to strongly unequal, the two lateral commonly slightly larger than the two adaxial, the abaxial stamen when present commonly slightly to markedly smaller than the others, sometimes reduced to a staminodium; very rarely 1–2 extra stamens, antepetalous; staminodes 0–1(–5), very short compared to the fertile stamens, total organs in the androecium never exceeding 10; reduced filaments less than six times the length of the anther, 1–3 mm long, glabrous, thick, usually exposed, sometimes enveloped by tissue of the base of the anther; anthers basifixed, introrse, lanceolate in outline, erect to curved, twisted or not, sometimes papillate, commonly changing color during anthesis from cream or yellow to reddish or brownish, densely golden- or brown-pubescent to glabrous, free but very close to each other, commonly touching the gynoecium at anthesis, sometimes partially covering it, bearing two thecae and four sporangia, the locules later reduced to two by deterioration of tissue between them, the two dorsal sporangia slightly longer than the two ventral ones, dehiscence sub-terminal poricidal, the two pores formed at the apices of the two dorsal sporangia on their ventral side above the apices of the two ventral sporangia, later merging into a single opening, surrounded by hygroscopic tissue functioning to close the openings when wet; pollen spherical, tricolpate, colpi elongated, exine ornamentation punctate; gynoecium monocarpelar or very rarely composed of two carpels, laterally compressed, sessile to subsessile, green, densely pubescent throughout or only along the abaxial suture, indumentum golden, brown or white, carpel sometimes curved towards the abaxial side of the flower, style usually curved towards the adaxial side of the flower, green, glabrous, stigma globose, papillate, ovules 1 per carpel. Fruits samara, indehiscent, lignified, strongly compressed laterally, elliptical to oblong to asymmetrical, sessile, base symmetrical to strongly asymmetrical, truncate to obtuse, apex symmetrical, rarely asymmetrical, usually obtuse to cuspidate to acuminate, more rarely mucronate to acute, glabrous to sparsely pubescent microscopically, green to reddish when young, red, vinaceous, purple, brownish, or yellow to orange when mature, with or without yellow or pink to red marks along the veins, reddish to brown when senescent, epicarp lignified, mesocarp fibrous, endocarp smooth; seminiferous nucleus occupying almost the entire fruit or just the central region, venation with two conspicuous main veins diverging from each other at or somewhat above the base of the fruit, outlining the seminiferous nucleus, delimiting it from the dorsal and ventral wings, and meeting again at the fruit apex (i.e., more or less paralleling the fruit margins). Seeds 1, 2.6–3.8 × 1.2–2.3 cm, exarillate, flat, elliptical, orange or cream, testa smooth, endosperm gelatinous, transparent, cotyledons elliptical, light green, deciduous after germination; hypocotylradicular axis straight and positioned in the central basal region of the cotyledons; plumule and two to four leafprimordia little to well developed. Seedlings with first two eophylls unifoliolate, usually paired and opposite, less commonly three and whorled, few subsequent eophylls unifoliolate and alternate, subsequent eophylls trifoliolate and alternate, usually ovate, leaflet base cordate or truncate, internodes reduced or not.

Diagnosis: — Martiodendron can be distinguished from the other genera of Fabaceae by the following combination of characteristics: imparipinnate leaves with alternate leaflets; developed axillary buds; distichous thyrsoid inflorescences; lanceolate flower buds; five strongly reflexed sepals in anthesis; five yellow to orange petals; four to five stamens positioned closely together, with elongate and lanceolate anthers (more than seven times the length of the reduced filaments), with poricidal dehiscence; an elliptical, strongly laterally compressed carpel, monospermic; indehiscent and compressed samaras, with an evident seminiferous nucleus located centrally between the two wings, and two main veins branching from or near the base, enclosing the seminiferous nucleus, and meeting again at the fruit apex.

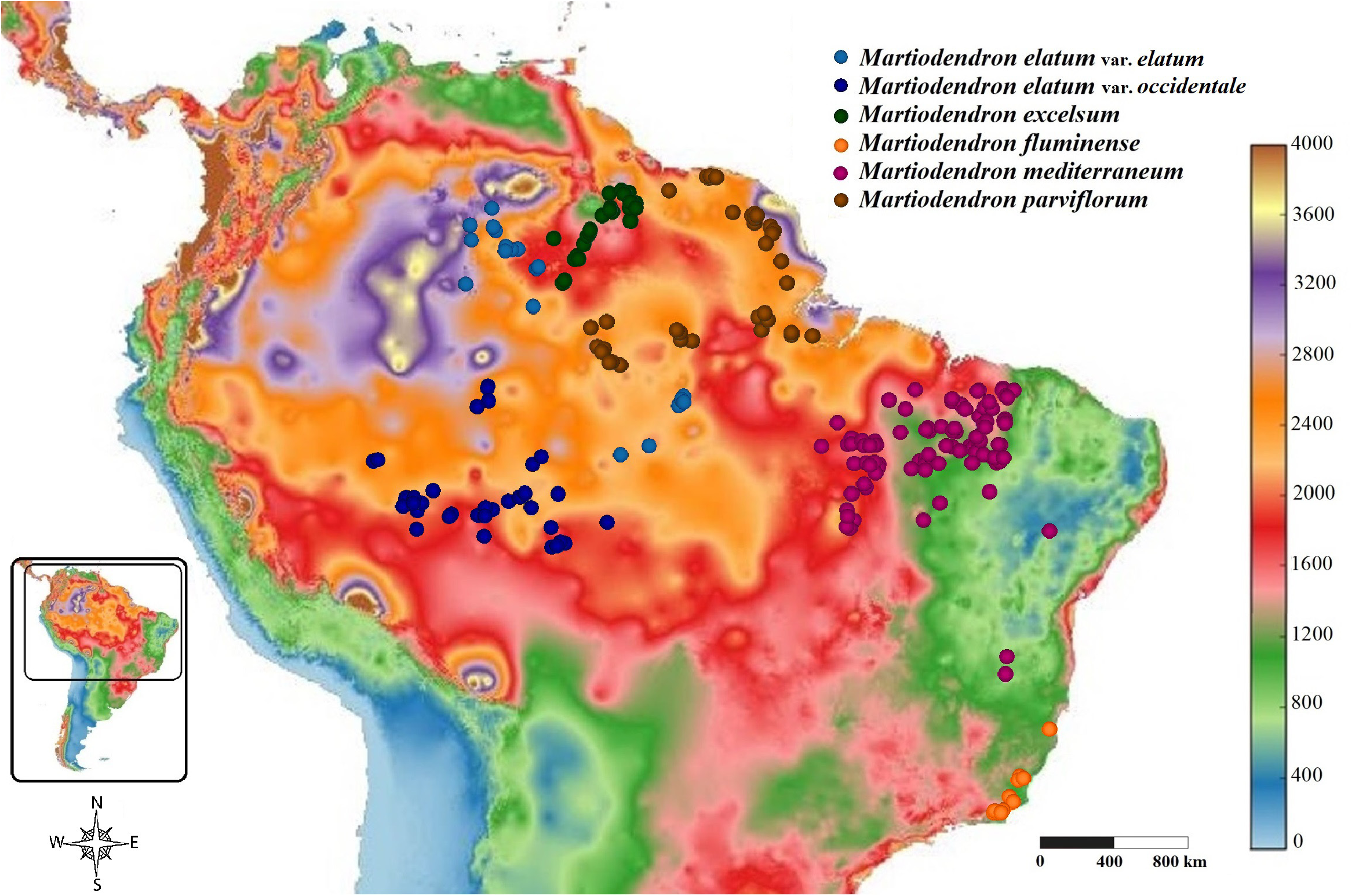

Distribution, Habitat, Biogeographical Patterns, and Ecology: — Martiodendron occurs in the following countries: Venezuela, Guyana, Suriname, French Guiana, Bolivia, and Brazil. It perhaps also occurs in Colombia and Peru (see M. elatum ), although its presence in those countries has not yet been confirmed. In Brazil, it has been recorded in the states of Mato Grosso, Rondônia, Acre, Amazonas, Roraima, Amapá, Pará, Tocantins, Maranh ã o, Piauí, Bahia, Minas Gerais, Espírito Santo, and Rio de Janeiro. The genus occurs in varied vegetation types, from dense rainforests to seasonal semideciduous forests and savannas, and rarely in arboreous Caatinga. It is most diverse in upland rainforests but also occurs in varzeas, igapós, and marshy areas.

In the present work, only M. elatum was found in Venezuela. However, Stergios in Steyermark et al. (1998) in the Flora of the Venezuelan Guayana, mentions three species for the region, M. elatum , M. excelsum and M. mediterraneum . However, no specimen was cited for M. excelsum , and the characterization of the species in both the key and the description of that work diverges from the concept of the species advanced by Koeppen & Iltis (1962) and adopted in the present work. The illustration contains a specimen in flower of M. elatum var. elatum and a separate fruit of M. excelsum . The key for this species indicates characteristics of M. elatum , such as long leaflets. And also, characteristics of M. excelsum , such as the laterally glabrous carpel, so the mixture of specimens from different species is a possible explanation. The authors also mention that the species is represented by large trees occurring in montane forests, further evidence that at least some of the specimens observed are not representatives of M. excelsum . Nevertheless, it seems likely that M. excelsum does occur in Venezuela near its borders with Roraima and Guyana, where populations of that species have been documented. As for M. mediterraneum , only one sterile specimen was cited by Stergios (1998), and again its characterization in that work is inconsistent with the review by Koeppen & Iltis (1962), such as leaflet color in exsiccates, level of impression of the vein and type of indumentum of the leaflet, all strongly variable characters. The size presented for leaflets is consistent with that found in individuals of M. excelsum and is mentioned as being a small tree from savannah areas, also consistent with the species M. excelsum . In the description of M. elatum , again, non-distinguishing characters are presented. In addition, they mentioned the leaflets were 16–18 cm long, a size never observed in this work. Specimens are also not cited. Unlike M. elatum , whose occurrence in this work is confirmed in Venezuela, and M. excelsum , whose existence in Venezuela is considered likely, although not confirmed, we consider it highly improbable that M. mediterraneum , here considered to be endemic to the savannas and caatingas of eastern Brazil, occurs in Venezuela.

The distributions of the five species of Martiodendron appear to be allopatric, with no observed cases of overlap between them. However, some of the intervening areas between distributions are poorly collected, leaving the possibility of limited co-occurrence of species to be confirmed (i.e. parapatry). In the Brazilian state of Amazonas, we have two species that do not co-occur: M. elatum occurring in its northwest region (Rio Negro basin, Barcelos and Santa Isabel region to the border with Venezuela), west (Coari), south and southeast (from the Purus River basin to the municipalities of Humaitá and Borba along the border with Pará); and M. parviflorum occurring in its northeast region, from Manaus to Pará, following the northern bank of the Amazon River. In Pará, there are three species that do not co-occur: M. elatum in the southwest and west (Tapajós River); M. parviflorum in the north, in the basins of the Trombetas, Paru, and Jari Rivers (almost always north of the Amazon River or, when on the south bank, very close to it, in the Melgaço and Caxiuan ã region); and M. mediterraneum , in the extreme east (near the border with Maranh ã o, in the Araguaia River basin). Nevertheless, the overall pattern strongly supports the importance of geographic isolation in the speciation history of the genus. In some cases, geographical barriers separate the distributions of species. For example, both M. parviflorum and M. excelsum appear to be isolated from M. elatum by major rivers, with M. parviflorum and M. excelsum occurring almost always north of the Amazon River and east of the Branco River, and M. elatum occurring either south of the Amazon River or north of it, but only west of the Branco River. Martiodendron fluminense , restricted to low elevation coastal areas of eastern and southeastern Brazil, is strongly isolated from other species by the central Brazilian plateau. However, some populations of M. mediterraneum reside within the plateau several hundred km from the nearest populations of M. fluminense . Likewise, M. parviflorum and M. excelsum seem to be partially isolated by the high elevations of the Guiana shield ( Figure 15 View FIGURE 15 ). In other cases, geographical isolation is reinforced by geographically structured differences in habitat preference. For example, M. mediterraneum generally prefers drier habitat than the other species of the genus and also occurs at higher elevations, usually at 200–600 m, with some specimens found up to 1000 m. In contrast, the other four species are found at elevations below 200 m. This perhaps accounts for the gaps between its distribution and those of M. elatum and M. parviflorum . Martiodendron excelsum , on the other hand, is the only species of the genus that is strongly associated with riverine habitats; it occurs most often in seasonally inundated varzeas, as well as in campinaranas, whereas M. elatum and M. parviflorum , which have geographical distributions adjacent to that of M. excelsum , are more associated with upland “terra firme” forests. It is also worth noting that the majority of Martiodendron species do not seem to be related to flooded environments, despite being associated with regions close to large river courses, a pattern also observed in the related genus Apuleia (Falc ã o et al., in prep) and Dialium (Falc ã o et al., 2016; 2020b), while M. excelsum presents a distributional pattern more similar to the related genus Dicorynia (Falc ã o et al., 2022).

Precipitation may be significant in structuring the distributions of species of Martiodendron , an observation evidenced by the different vegetation types inhabited by each species. The distribution of M. parviflorum experiences relatively high rainfall (2000–2800 mm per year). The distribution of M. elatum spans a broader rainfall gradient, with most populations of variety occidentale occurring in areas of intermediate precipitation (1600–2000 mm), and populations of variety elatum in wetter areas (2000–2800 mm). Similarly, the distribution of M. excelsum occupies areas with intermediate precipitation (1600–2000 mm), while that of M. mediterraneum spans a broader gradient, from intermediate areas (1600–2000 mm) to much drier ecotonal areas with the Caatinga (400–1200 mm). Finally, although M. fluminense occurs in one of the driest regions on average in southeastern Brazil (400–1200 mm), the species generally occurs in more humid, topographically structured rainforest microsites ( Figures 15–16 View FIGURE 15 View FIGURE 16 ).

Etymology: —Bentham initially named the genus Martiusia , in honor of the German naturalist Carl von Martius (1794–1868) and later renamed it Martia ( Bentham 1840) . Subsequently, Gleason (1935) proposed Martiodendron , using the Greek suffix dendron (tree).

Taxonomic Comments: —Among taxa of Dialioideae , Martiodendron is most similar, concerning the proliferation/reduction of floral parts, to the genera Koompassia , Kalappia , Zenia , Androcalymma , and Uittienia , two of the four species in Storckiella ( Storckiella australiensis J.H. Ross & B. Hyland , Storckiella pancheri Baill. ) and one of the 34 species in Dialium ( Dialium englerianum Henriq. ). All of these taxa have flowers with five sepals, five petals, and four to five stamens, while other taxa of Dialioideae have either 10 to 13 stamens or flowers with significantly reduced parts in the calyx, corolla and/or androecium ( Tucker 1998; Zimmerman et al., 2013; Falc ã o et al., 2020a; in prep). Among the most similar taxa, Martiodendron shares with two of the three species of Koompassia and Storckiella australiensis anthers that are much longer than the significantly reduced filaments. Martiodendron can be distinguished from Koompassia by its larger flowers, with the petals, sepals, anthers, and carpel much longer and the last three also narrower; reflexed (vs. non-reflexed) sepals at anthesis, yellow (vs. white to cream to greenish) petals, broader filaments, and longer style. It differs from Storckiella australiensis by its larger flowers and longer and narrower sepals and anthers. From Kalappia , besides the shorter filaments, it differs by its radially disposed and narrower petals at anthesis (vs. two abaxial petals partially covering the androecium), narrower reflexed (vs. nonreflexed) sepals at anthesis, and more elongate nonspurred (vs. spurred) anthers. From Zenia it differs by the absence (vs. presence) of a receptacular disk, longer, reflexed (vs. non-reflexed) sepals at anthesis, yellow (vs. red) corolla, and narrower anthers. From Androcalymma , it differs by its larger flowers, the erect (vs. curved over the carpel) anthers with ungrooved (vs. grooved) filaments, much longer carpel, narrower and reflexed (vs. non-reflexed) sepals at anthesis, and five practically homomorphic (vs. three petaloid) sepals. From Uittienia , it differs by the absence (vs. presence) of a receptacular disk, larger flowers, longer, and narrower sepals and anthers, anthers with poricidal (vs. rimose) dehiscence, non-stipitate (vs. long-stipitate) carpel, and longer style. Finally, from Dialium englerianum , it differs by the absence (vs. presence) of a receptacular disk, larger flowers, longer, reflexed (vs. non-reflexed) sepals at anthesis, yellow (vs. white) and more developed petals, and much more elongate anthers; ( Chun, 1946; van Steenis 1948; Kostermans 1952; Maingay, 1873; Koeppen & Iltis, 1962; 1963; Falc ã o et al., 2020a; present work; in prep).

Martiodendron has large monospermic samaras with a seminiferous nucleus demarked by dorsal and ventral veins and bordered by two wings, similar only to those of Koompassia . The fruits in Martiodendron can be distinguished from those in Koompassia mainly by being wider and flat (vs. generally narrower, and sometimes contorted at the base or tapered at the central portion). The fruits in other Dialioideae are polyspermic samaroid with one reduced wing, globose camaras, or more rarely drupes or legumes ( Maingay, 1873; Falc ã o et al., present work). In a proposal to reclassify the fruit types in Dialioideae genera (Falc ã o et al., 2021; 2022; present work; in prep), primarily based on the classification by Barroso et al. (1999), we adapted some concepts related to samaroid legumes and samaras to the morphological variations of the subfamily fruits. Thus, we maintain the classification by Barroso et al. (1999) for the fruits of Martiodendron as samaras. The samaras of the genus are necessarily monospermic, with two well-developed wings along both sides of the fruit, clearly delimited from the seminiferous nucleus by two conspicuous veins. The wings are less developed in M. excelsum than in the other species.

Koeppen & Iltis (1962) divided Martiodendron in two series: Elatae and Excelsae, the latter containing only M. excelsum . The main differences between the series are, respectively, the presence of expanded wings in fruits and fully pubescent carpels (vs. reduced wings and laterally glabrous carpels). Despite this morphological basis for the Koeppen & Iltis’ classification, we refrain from adopting it here pending ongoing phylogenetic study of the genus (Falc ã o et al., in prep). To date, the only phylogenetic study that included more than a single species of the genus ( Zimmerman et al., 2017) did not reject the notion that M. excelsum is the sister taxon to a clade comprising the other species of the genus, as predicted by Koeppen & Iltis’ classification. However, we discovered that the sampled specimen identified as M. parviflorum in that work is actually a M. mediterraneum , and that some of the sampled specimens identified as M. mediterraneum are actually M. fluminense . Thus, some of the relationships presented in the work must be reinterpreted.

Among the five species of the genus, three are individually highly distinct, showing consistent differences with other species in multiple morphological characters, and relatively little variation within their circumscriptions: Martiodendron excelsum is easily recognizable by its few, relatively wide leaflets, laterally glabrous carpels, and pubescent anthers; M. parviflorum by its pubescent anthers, uniformly pubescent carpels, and falcate floral buds; and M. fluminense , for having five stamens and inflorescences branching into cymes with primary and secondary axes not elongated. On the other hand, M. mediterraneum and M. elatum are variable and morphologically similar species. This similarity was not fully appreciated by Koeppen & Iltis (1962) due to the small number of specimens of both taxa available for study at the time. The authors suggested that M. mediterraneum always had smaller leaflets than those of M. elatum . However, with the larger number of specimens observed here, we verified the morphological variation of M. mediterraneum , which can rarely present leaflets as large and long as those of M. elatum . Nevertheless, the vast majority of specimens can be assigned to species by the combination of leaflet size and shape, plant size, and fruit size and shape. In addition, the two species have non-overlapping geographical distributions and different habitat preferences.

The shape and size of the axillary buds in Martiodendron is helpful to differentiate some of its species. Although M. excelsum , M. fluminense and M. mediterraneum have similar bud sizes and shapes (but with some specimens of M. fluminense with usually small buds), M. elatum has much larger buds than the other species, and M. parviflorum has the buds almost always smaller, with the apex acute (vs. almost always acuminate to cuspidate in the other species). As there is some overlap in the measurements of these characters, such differentiation should be taken with caution.

The presence of clear gelatinous exudate on trunks is commonly cited for the genus. Mori et al. (2002), in the flora of central French Guiana, mention that M. parviflorum does not produce exudate, however the paucity of data about the feature makes it difficult to ascertain its taxonomic value. Other related genera in Dialioideae as Dialium and Dicorynia also present exudate, being red in Dialium ( Rojo 1982; Falc ã o et al., 2016; 2022).

The presence/absence of asymmetric ventral sporangia (figure 13H, K, M) and contorted anthers (figure 13Q) are the only significant variations observed in anthers of the genus. These appear, however, to be exceptionally plastic characters within species. In the case of asymmetric sporangia variation was observed even among flowers of the same individual in most species, whereas in the case of contorted anthers, variation was noted among individuals of the same population.

Gelatinous endosperm (figures 12F and I) was observed by us in M. elatum , M. fluminense , and M. mediterraneum , and by Hartmann & Rodrigues (2014) in M. excelsum .Although we were unable to obtain intact seeds of M. parviflorum , its fruits are similar to the other species, suggesting that it also has gelatinous endosperm. As such, we concur with Koeppen & Iltis (1962), Oliveira & Pereira (1984), Silva et al. (2005) and Hartmann & Rodrigues (2014) that the feature is characteristic of the entire genus and disagree with the suggestion of Gunn (1991) that Martiodendron lacks endosperm. Among the neotropical genera of Dialioideae , the endosperm of Martiodendron is most similar to that found in Dicorynia , which is gelatinous only in the margins (Falc ã o et al., 2022), while in Apuleia , Dialium , and Poeppigia the endosperm is completely solid (Falc ã o et al., 2016; 2021; in prep).

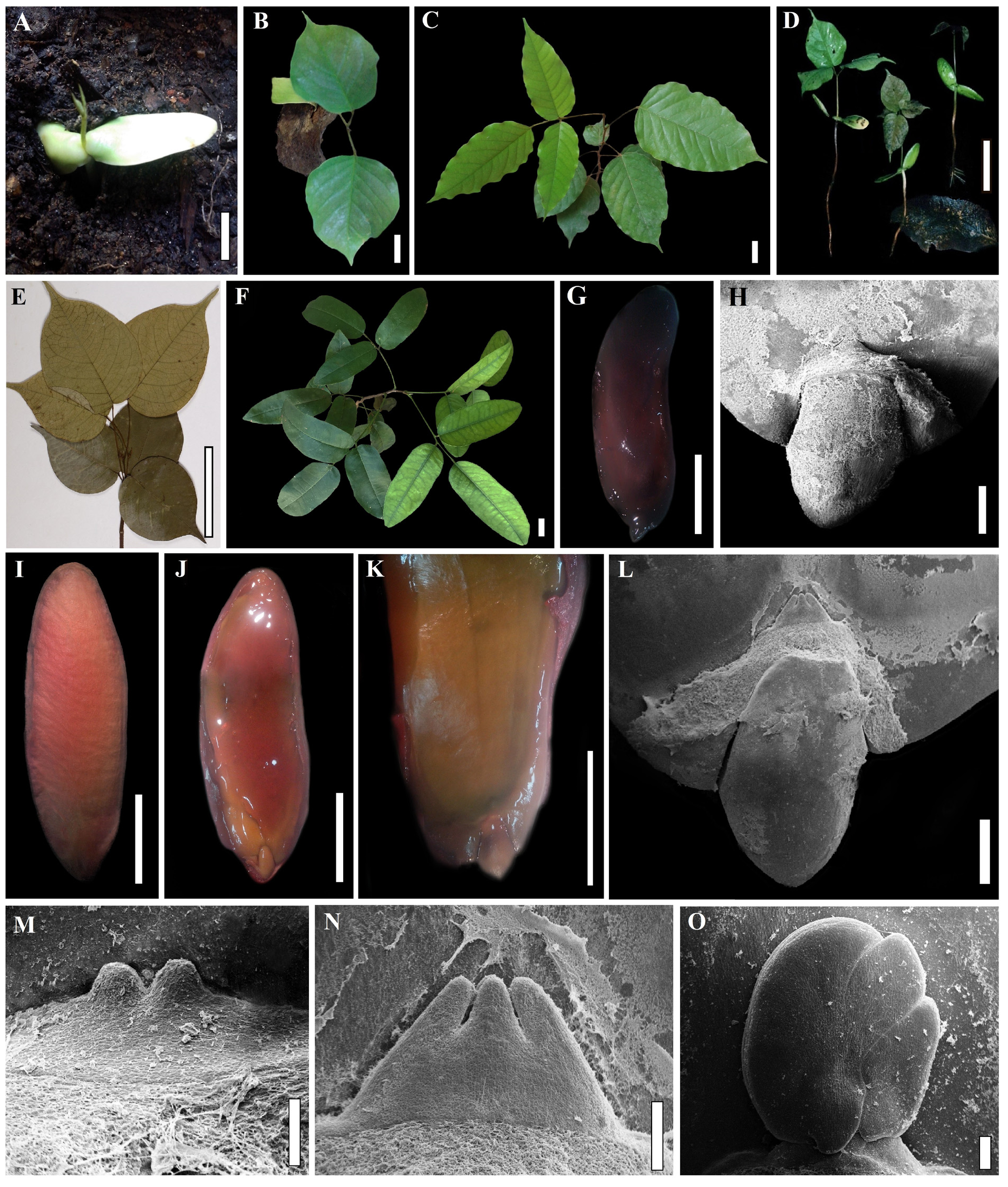

Martiodendron seedlings most closely resemble those of the neotropical genera Dialium , Dicorynia , and Apuleia (Falc ã o et al., 2022; in prep). They have well-developed leaf primordia in the seed (figure 12L–N), the first eophylls unifoliolate, broad, and with a cordate to truncate base, subsequent eophylls trifoliolate, and the leaves imparipinnate with alternate leaflets ( Figure 12A–E View FIGURE 12 ). On the other hand, Poeppigia (Falc ã o et al., 2021), differs from the other genera in that it has inconspicuous leaf primordia, only the first pair of unifoliate eophylls, narrow and with a wedge base, and the following eophylls already with several paripinnate leaflets. More comparisons between seedlings of the group were made by Hartmann & Rodrigues (2014).

No significant differences were found in the morphology of seeds, embryos (figure 12), anthers (figure 13), and pollen grains (figure 14) among the species and varieties of Martiodendron . Some interspecific differences were observed in the seedlings of some species (figure 12), although our sampling of these characters did not include material of all taxa of the genus. Morphological observations of seeds, embryos, anthers, and pollen grains were made from in situ collections and exsiccates. Information about M. excelsum seedlings and seeds was obtained from Hartmann & Rodrigues (2014), and the following comparisons were made: seedlings of M. fluminense , M. mediterraneum , M. parviflorum (present work) and M. excelsum ( Hartmann & Rodrigues, 2014) ; seeds and embryos of M. elatum , M. fluminense , and M. mediterraneum (present work) and M. excelsum ( Hartmann & Rodrigues, 2014) ; anthers and pollen of all species (present work).

Our observations on seedling morphology corroborate those obtained by Hartmann & Rodrigues (2014). The seedlings of M. excelsum and M. fluminense do not show significant differences from each other in any of their developmental stages. The seedlings of M. mediterraneum are also similar to these species in the first developmental stages, but when the first trifoliolate eophylls emerge, they are more oblong and chartaceous ( Figure 12F View FIGURE 12 ), while in M. excelsum and M. fluminense , the leaflets of the trifoliolate eophylls are ovate ( Figure 12C View FIGURE 12 ). Thus, the first eophylls are always two and opposite in M. excelsum , M. mediterraneum , and M. fluminense , while the subsequent eophylls are alternate and the internodes between them elongate (present work: Figure 12B–C, F View FIGURE 12 ; Hartmann & Rodrigues, 2014). On the other hand, M. parviflorum presents a quite variable arrangement of the first eophylls, with the first two opposite and the subsequent ones alternate and separated by elongate internodes, or the first eophylls three and practically verticillate with internodes highly reduced, and the subsequent eophylls alternate, but congested, as can be seen in Figure 12D–E View FIGURE 12 . Future studies on seedlings from M. elatum may expand this picture.

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.

|

Kingdom |

|

|

Phylum |

|

|

Class |

|

|

Order |

|

|

Family |

Martiodendron Gleason

| Falcão, Marcus José De Azevedo, Torke, Benjamin M., Garcia, Gabriel Santos, Silva, Guilherme Sousa Da & Mansano, Vidal De Freitas 2023 |

Martiusa

| Benth. & Hook. f. 1865: 571 |

Martiusia

| Benth. 1840: 84 |

Martia

| Benth. 1840: 146 |