Diptera biodiversity inventory

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/ 10.11646/zootaxa.3949.3.1 |

|

publication LSID |

lsid:zoobank.org:pub:43B43A7C-644C-4B46-BAAF-522C3C1FDC7D |

|

DOI |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6120297 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/BE4D120D-ED07-B525-FF26-FCDBBB2E7919 |

|

treatment provided by |

Plazi |

|

scientific name |

Diptera biodiversity inventory |

| status |

|

Zurquí all Diptera biodiversity inventory (ZADBI)

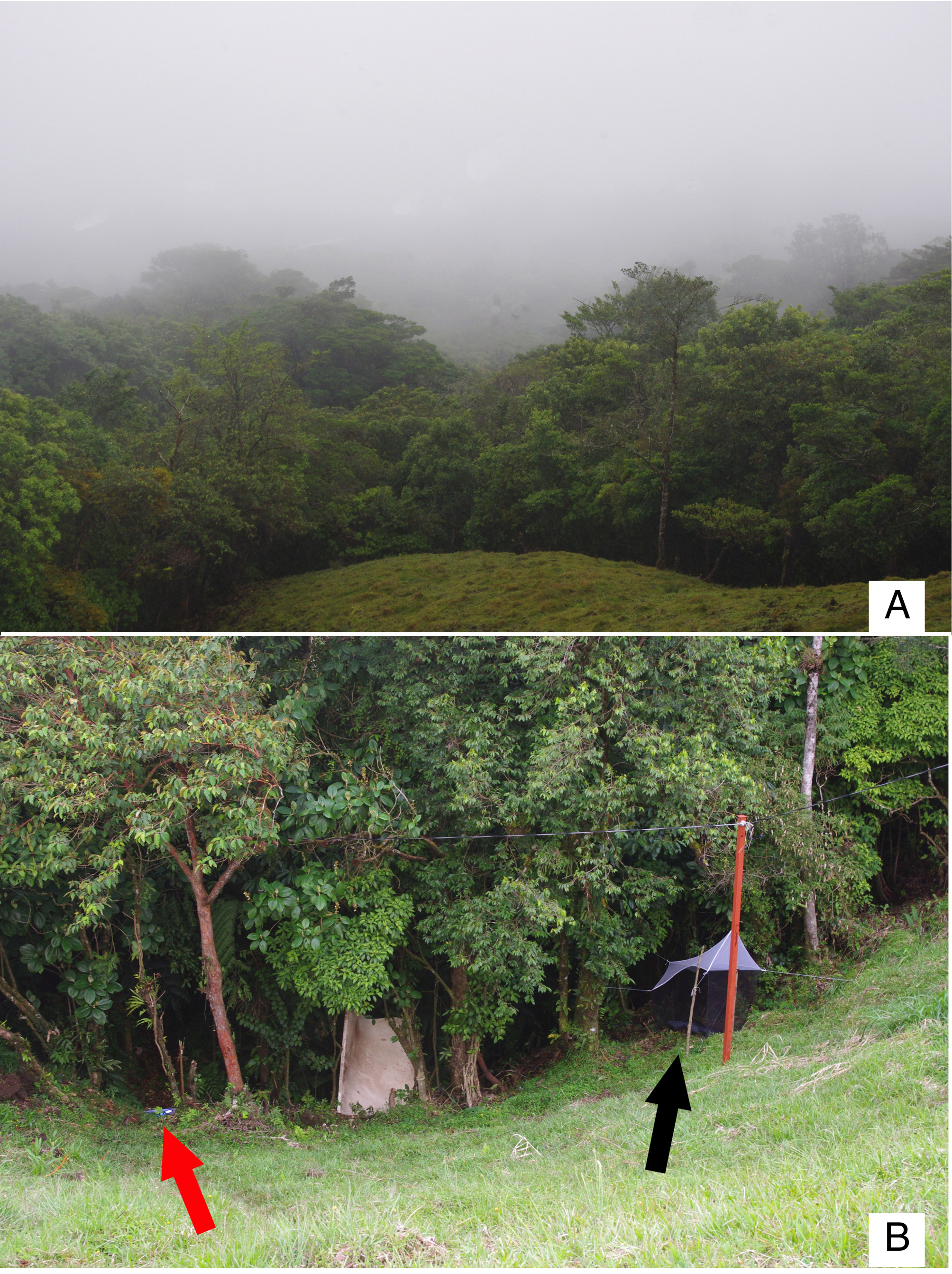

These perspectives led us to propose an innovative Diptera survey of a mid-elevation tropical cloud forest to the National Science Foundation ( USA) (see http://phorid.net/zadbi/ and YouTube link https://www.youtube.com/ watch?v=HkROS6-K02U). We chose a study site at Zurquí de Moravia (hereafter "Zurquí), San José Province, Costa Rica, for a number of reasons. From previous prospecting, this site was known among some entomologists as remarkably rich in insect species ( Hanson 2000). The site is also easily accessible, about a 30 minute drive northeast of San José and, although privately owned, we had assurances from the owner, Jorge Arturo Lizano, that it will remain protected. Our study site, at 1585 meters elevation, was limited to a 150 x 266 meter area ( Fig. 1 View FIGURE 1 ) that included a small ridge, a permanent stream, a temporary stream and a variety of vegetation, including some disturbed habitat (pasture) ( Figs. 2–3 View FIGURE 2 View FIGURE 3 ). It is abutting the extensive and virtually pristine Braulio Carillo National Park. Our baseline sampling was a single Malaise trap set on the ridge at the edge of the forest ( Fig. 2 View FIGURE 2 B), to be employed for one year, the results of which were to be studied by all cooperating systematists ( Table 1). Supplementary sampling is discussed below.

Family Collaborator

Tipulidae JonK.Gelhaus

Bibionidae Dalton de Souza Amorim Mycetophilidae Peter H. Kerr

Lygistorrhinidae Peter H. Kerr

Sciaridae Heikki Hippa, Pekka Vilkamaa Cecidomyiidae MathiasJaschhof

Ceratopogonidae Art Borkent, Gustavo R. Spinelli, Maria M. Ronderos Simuliidae PeterAdler

......continued on the next page Family Collaborator

Culicidae ThomasJ.Zavortink

Scatopsidae Dalton de Souza Amorim

Psychodidae Gregory R. Curler, Sergio Ibáñez-Bernal, Gunnar M. Kvifte

Anisopodidae Dalton de Souza Amorim

Stratiomyidae Norman E. Woodley

Xylophagidae Norman E. Woodley

Asilidae EricM.Fisher

Dolichopodidae Marc Pollet (coord.), Daniel J. Bickel, Scott E. Brooks, Renato Capellari, Neal L.

Evenhuis, Stefan Naglis, Justin Runyon

Empididae Jeffrey M. Cumming, Bradley J. Sinclair

Phoridae BrianV.Brown

Syrphidae Christian Thompson, Manuel Zumbado

Pipunculidae Jeffrey H. Skevington

Chloropidae TerryA.Wheeler

Sphaeroceridae Stephen A. Marshall

Drosophilidae David A. Grimaldi

Tephritidae AllenL.Norrbom

Micropezidae Stephen A. Marshall

Pseudopomyzidae Stephen A. Marshall

Conopidae JeffreyH.Skevington

Lonchaeidae Cheslavo A. Korytkowski

Platystomatidae Valery A. Korneyev

Richardiidae Valery A. Korneyev

Lauxaniidae Stephen D. Gaimari

Chamaemyiidae Stephen D. Gaimari

......continued on the next page Family Collaborator

Anthomyzidae Kevin N. Barber Aulacigastridae AlessandraRung Periscelididae AlessandraRung Heleomyzidae Norman E. Woodley Curtonotidae Stephen A. Marshall Diastatidae WayneN.Mathis Ephydridae WayneN.Mathis Inbiomyiidae Brian V. Brown Muscidae JadeSavage

Tachinidae D. Monty Wood, Manuel Zumbado Hippoboscidae Carl W. Dick

Scathophagidae VernerMichelsen Anthomyiidae VernerMichelsen Fanniidae JadeSavage

Calliphoridae TerryWhitworth Sarcophagidae ThomasPape

To ensure that our samples would be fully identified we approached over 50 fellow systematists. Nearly all had been involved in the previously published MCAD ( Brown et al., 2009, 2011) and they gave enthusiastic endorsement of this new project when we approached them. As a community, Dipterists are in the enviable position of having experts who are available and willing to take on all of the 72 families discovered ( Table 1). When we said we wanted to do a Diptera inventory of the site, we meant a full inventory. In the parlance of the survey community, we wanted our project at Zurquí to be an "All Diptera Biodiversity Inventory ", which we named ZADBI for short. We incorporated all Diptera groups including those previously considered to be "impossible": Cecidomyiidae , Ceratopogonidae , Chironomidae , Phoridae , Sciaridae , Tachinidae , Tipulidae , and others.

As expected, many of the discovered species proved to be undescribed and, as such, are for the present given a morphospecies code number, entered into the database, and, if not described soon, will be housed in the established collections at the Instituto Nacional de Biodiversidad (INBio), Costa Rica and Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County, California, USA (LACM).

Our project is fortunate to have the support and collaboration of INBio, our "home base" in Costa Rica. The institution provides logistical support and serves as a center for incorporating results into their database and collection. To assist with sampling and curation of material we hired five technicians, all of whom were trained and had extensive previous field and lab experience at INBio ( Figs. 4–5 View FIGURE 4. A View FIGURE 5. A ). The individual talents of our team—Carolina Avila, Marco Moraga (who moved away during this study), Annia Picado, Wendy Porras, Elena Ulate, and Elvia Zumbado (more recently hired)—made our project possible. At the start of our project, most could already identify Diptera to at least family level and there was a high level of skill in sorting and preparing both slide-mounted and pinned material. Hiring locals had huge advantages in lower costs, less damage to specimens during transport from the field and also contributed to local structure and economy.

We also hired a project manager at the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County (Anna Holden for the first portion of our project and Estella Hernandez in the latter part) to oversee the mechanical details of our project including ordering supplies, helping to organize the technicians, assisting with the initial set up of sampling equipment, ensuring that specimens flowed well throughout our curatorial system and loans were arranged correctly. Our project manager also provided educational outreach at the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County. As a strong educational component of our project, the museum promoted flies in educational programming, offered resources for teachers, collaborated with the Encyclopedia of Life and encouraged the use of social media.

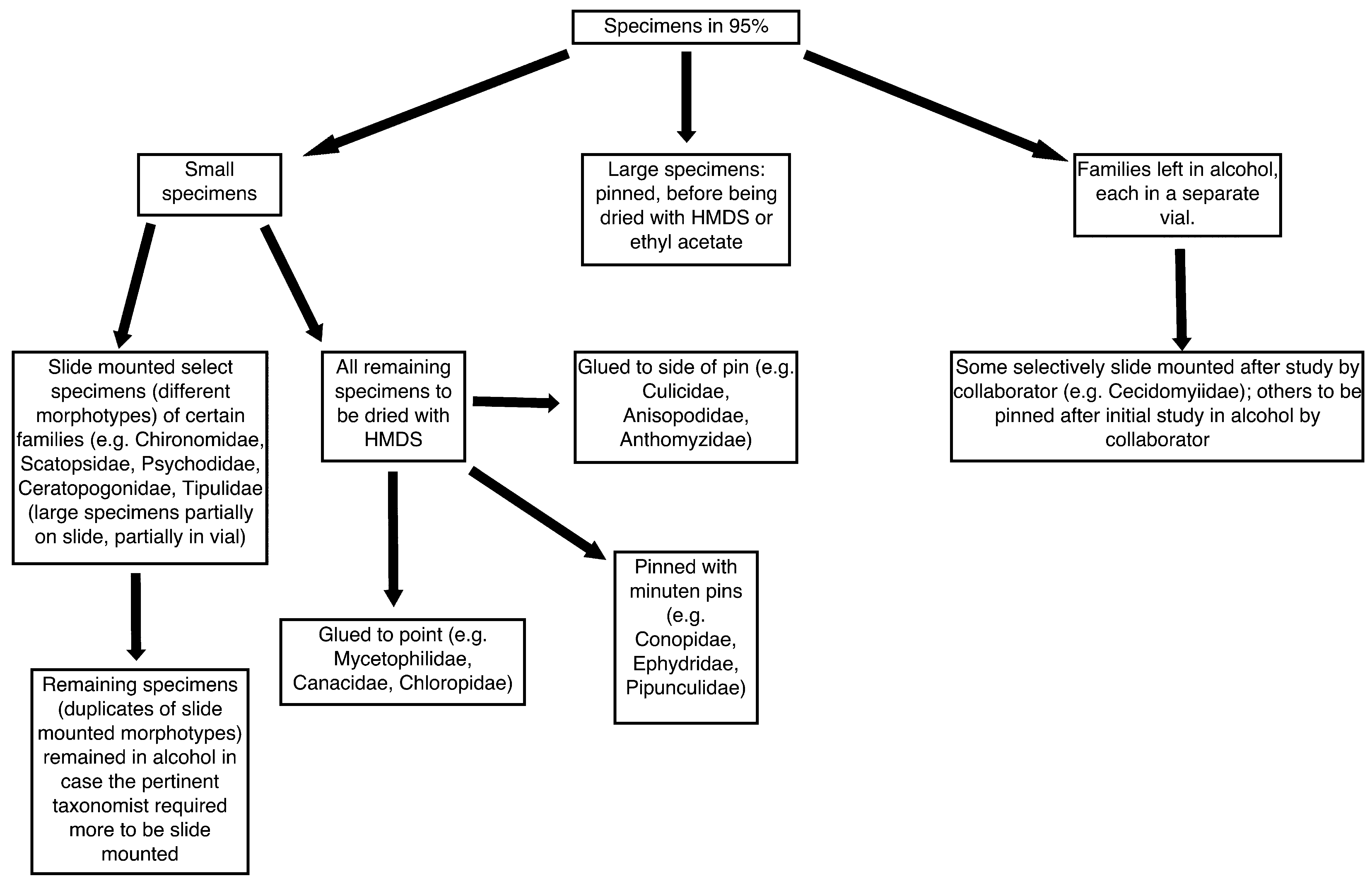

To ensure the highest levels of curation we approached each of our collaborators to ask for their exact requirements. Because of the nature of their groups and the history of their preparation, many had different curatorial requests. Some systematists, in addition, had their own idiosyncratic method for handling material. The result was the preparation of a 33 page protocol manual, detailing the curatorial needs for each family (summarized in Fig. 10 View FIGURE 10 ). Collaborators needing slide preparations, for example, differed in how they wanted dissected parts arranged and whether they wanted specimens in Euparal or Canada Balsam as the final mounting medium. Individuals requesting pinned specimens wanted their specimens either on points (white or gray paper), glued directly to the pin, pinned through the thorax or on secondary minuten pins. We needed to teach the technicians these various additional protocols. To ensure highest quality, we sent out an initial small batch of prepared specimens to each collaborator for them to give us their appraisal and further instructions. Our goal was to produce "perfect" specimens as far as possible. Generally, the resulting specimens were in very good to excellent condition and for collaborators, pleasurable to study. Each specimen was fully labeled, including a unique barcode number, and entered into a database, to be housed at LACM and duplicated at INBio (ATTA system). The care given to all specimens produced material allowing our collaborating systematists to immediately begin employing their expertise in distinguishing species.

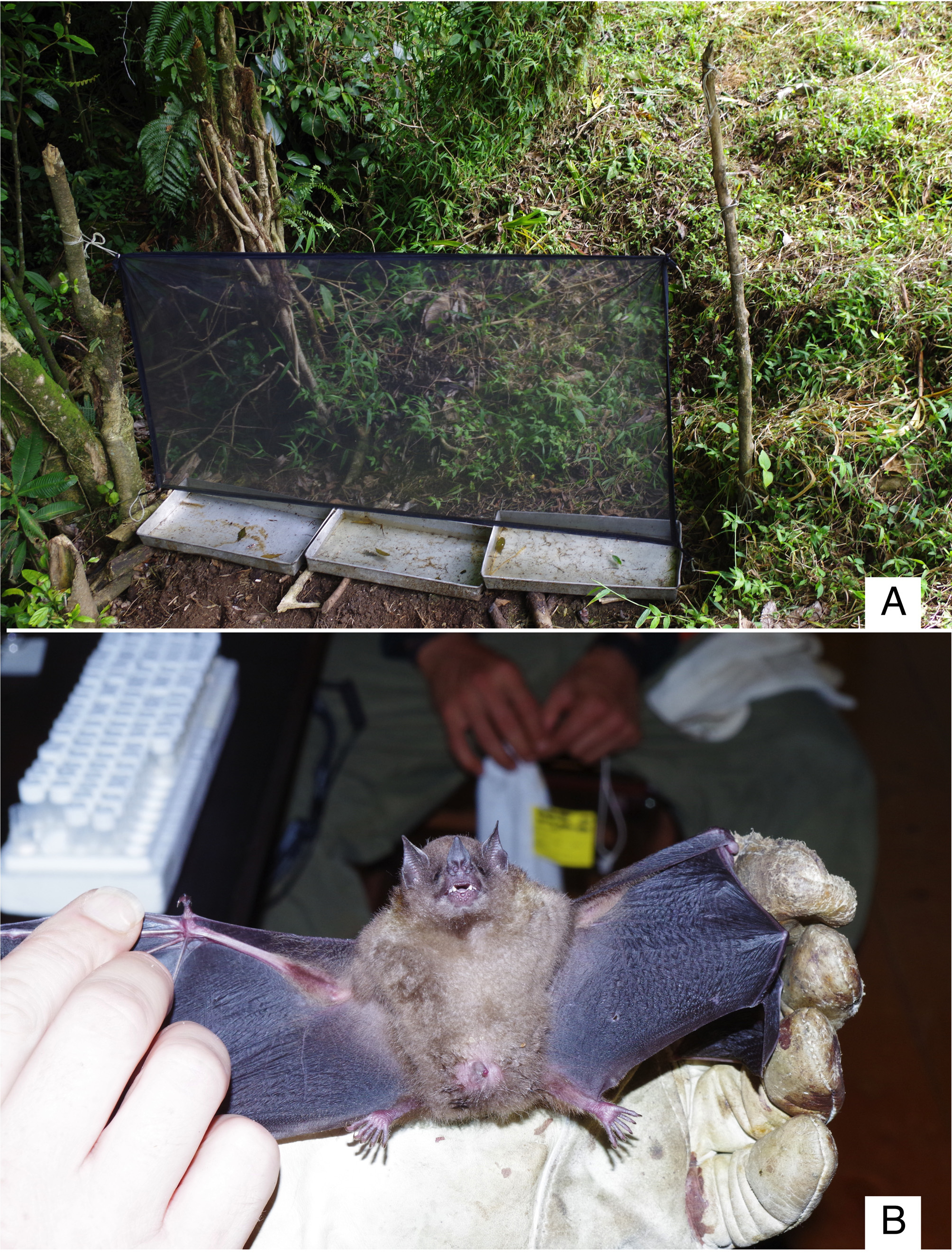

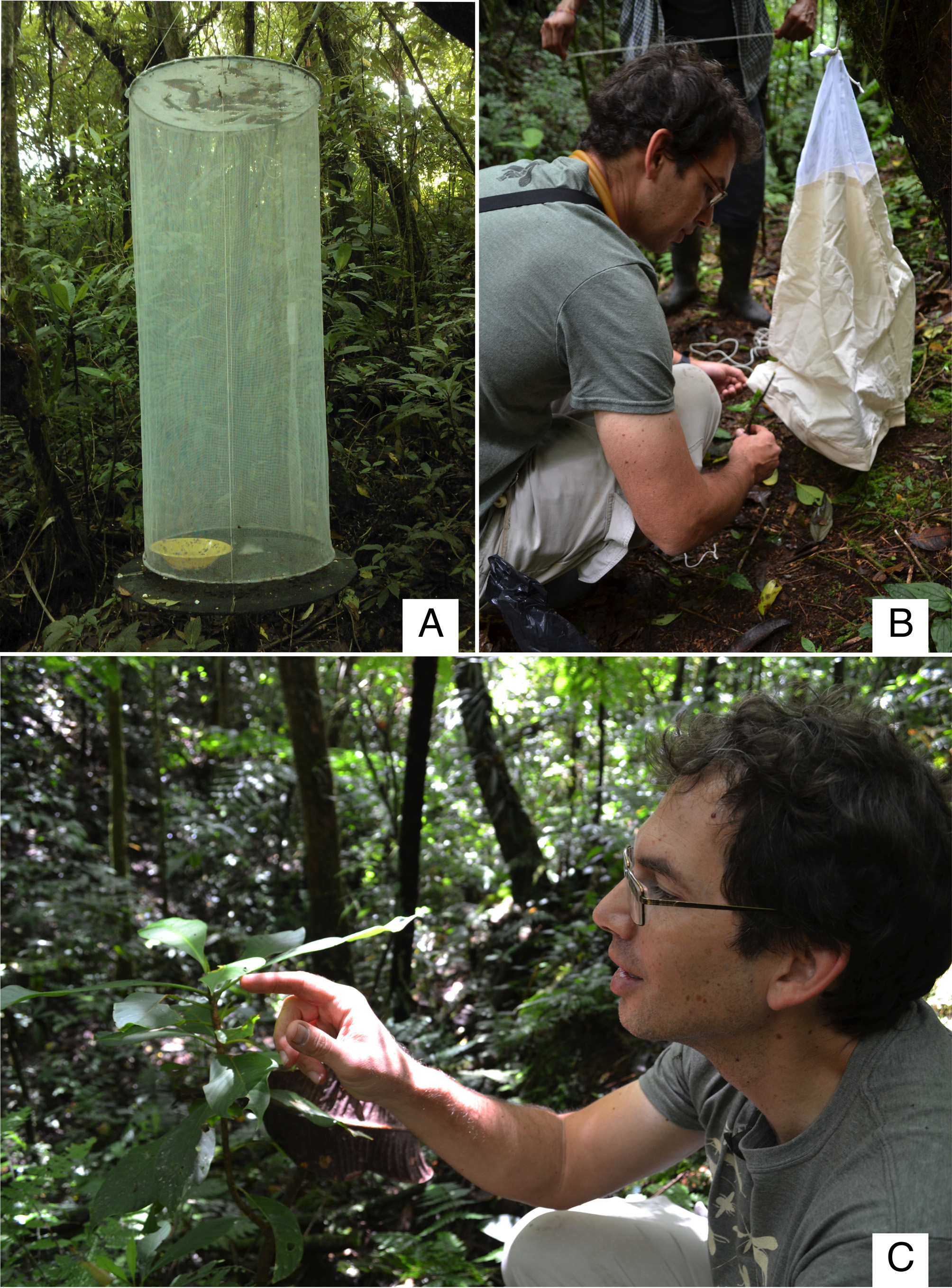

Our sampling with a single Malaise trap at Zurquí ( Fig. 2 View FIGURE 2 B) was proposed to our collaborators as the minimum requirement for identifying species. We also placed an additional continuous Malaise trap near the permanent stream at the bottom of the ravine, a habitat appearing substantially different to us ( Fig. 3 View FIGURE 3 A). Although Malaise traps were our primary collecting method, we were keenly aware that some flies would not be collected by this method alone. We therefore had a team of two technicians go to the site once a month for three days (including three nights) to utilize various other methods of collecting ( Figs. 6–9 View FIGURE 6 View FIGURE 7 View FIGURE 8 View FIGURE 9 ). We rented a cabin at the site for accommodation and storage of some traps when these were not in use (e.g. light traps). This effort resulted in numerous additional samples from techniques including hand collecting ( Fig. 9 View FIGURE 9 C), sweep netting ( Fig. 7 View FIGURE 7 C), three different types of light trapping (CDC, bucket traps, black light over pans of soapy water) ( Figs. 6 View FIGURE 6 B, 7A–B), baiting with various attractants (fruit, carrion) ( Figs. 9 View FIGURE 9 A–B), emergence traps ( Fig. 6 View FIGURE 6 A), a flight intercept trap ( Fig. 8 View FIGURE 8 A), yellow pan traps, and a canopy Malaise trap.

To make faunistic comparisons, we ran a Malaise trap at each of two more distant sites in Costa Rica, both at nearly the same elevation, in Tapantí National Park and Las Alturas, 40 and 180 km southeast of Zurquí, respectively, for the same one year period as that at Zurquí. This additional sampling substantially increased the amount of material of most groups. Even so, every collaborator wanted to study all the specimens from the supplementary trapping at Zurquí and nearly all also wanted the additional material from Tapantí National Park and Las Alturas.

Collecting by specialists can often strikingly increase the number of species obtained. A few examples illustrate this point. In the summer of 2013, we held the " Diptera Blitz " at Zurquí (see YouTube link https:// www.youtube.com/watch?v=HkROS6-K02U). Nineteen systematists were invited to use their specialized knowledge to obtain species that our trapping program might otherwise miss. Even with the plethora of collecting methods employed, it is often the case that a specialist in a particular group can zero in on those special microhabitats and obtain species not (or rarely) collected by mechanical means. One of these experts, retired Smithsonian Dipterist Wayne Mathis, raised the number of shore flies (family Ephydridae ) sampled at the site from three to 26 species. Additionally, he added three entire families to the inventory that our various traps had not collected ( Anthomyzidae , Diastatidae , Therevidae ). Another obvious specialized approach was by Carl Dick, who along with Kimball Garrett, netted bats and birds during the Diptera Blitz to obtain 10 species of two families of parasitic flies ( Streblidae , Hippoboscidae ) that lived only on these animals ( Fig. 8 View FIGURE 8 B). As a final example of very specific collecting, samples of black fly ( Simuliidae ) larvae were collected from the permanent stream ( Fig. 3 View FIGURE 3 B) and preserved in Carnoy's solution, allowing their chromosomes to be examined and thereby the species identified by Peter Adler.

The handling of material is a crucial component of a successful inventory ( Fig. 10 View FIGURE 10 ). Samples in the field were nearly entirely preserved in 95% ethanol; only hand-swept specimens of some larger and/or robust specimens were pinned directly after being collected. Alcohol material in variously sized containers was completely topped up with ethanol in the field to ensure that no sloshing occurred during transport to the laboratory. Such groups as Cecidomyiidae , Chironomidae and Tipulidae , amongst others, are often badly damaged in the initial stages of sample collection in other projects, meaning that these taxa are generally in too poor condition to study. Even slight jostling in alcohol can break the legs and antennae of the more sensitive taxa and great care in transport and subsequent handling is critically important. In the laboratory, samples were first databased and separated into fractions: non-Diptera and each of the different families of Diptera (some uncommon families were kept as a group and separated after further curation) ( Fig. 10 View FIGURE 10 ). Material which was to be further prepared as dried, pinned material using either ethyl acetate for larger specimens or HMDS ( Heraty & Hawks, 1998) for smaller, more delicate taxa ( Fig. 10 View FIGURE 10 ) included all specimens in the samples. Further specifics of pinning protocol followed our collaborators' wishes, as indicated above. Other taxa, to be dissected and placed on microscope slides, were generally more abundant and were first examined in ethanol and differing morphotypes selected for subsequent mounting in either Canada Balsam or Euparal ( Pinder 1989; specific processing varying somewhat by family). For some of these latter families, specimens were selected for slide-mounting by the specialist (all Cecidomyiidae , many Ceratopogonidae and some Psychodidae ), in others by the technicians who had been taught to mount every specimen even suspected of being different. Finally, a few researchers wished to receive their specimens in alcohol, ultimately preparing the specimens themselves, or returning these as identified specimens to be pinned or slide mounted at a later date. Each prepared specimen was databased when it was labeled (including a unique barcode number) and subsequently tracked as batches of specimens were sent to our specialists for identification. With each group of fully prepared specimens sent (and particularly for the first, small batch of specimens) we received feedback on the quality of specimen preparation and in some instances, fine-tuned the subsequent preparation by the technicians.

To track identifications, collaborators were directed to a dedicated website in which collecting data were indicated and species identification and gender could be inserted for each of their specimens. Unnamed morphotypes were indicated with a prefaced number (e.g. " Forcipomyia ZADBI-1" for an unidentified species of Ceratopogonidae ).

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.