Macaca nigra (Desmarest, 1822)

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6867065 |

|

DOI |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6863141 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/CE199B17-FFC2-FFC0-FAEC-6935F9D3FA53 |

|

treatment provided by |

Jonas |

|

scientific name |

Macaca nigra |

| status |

|

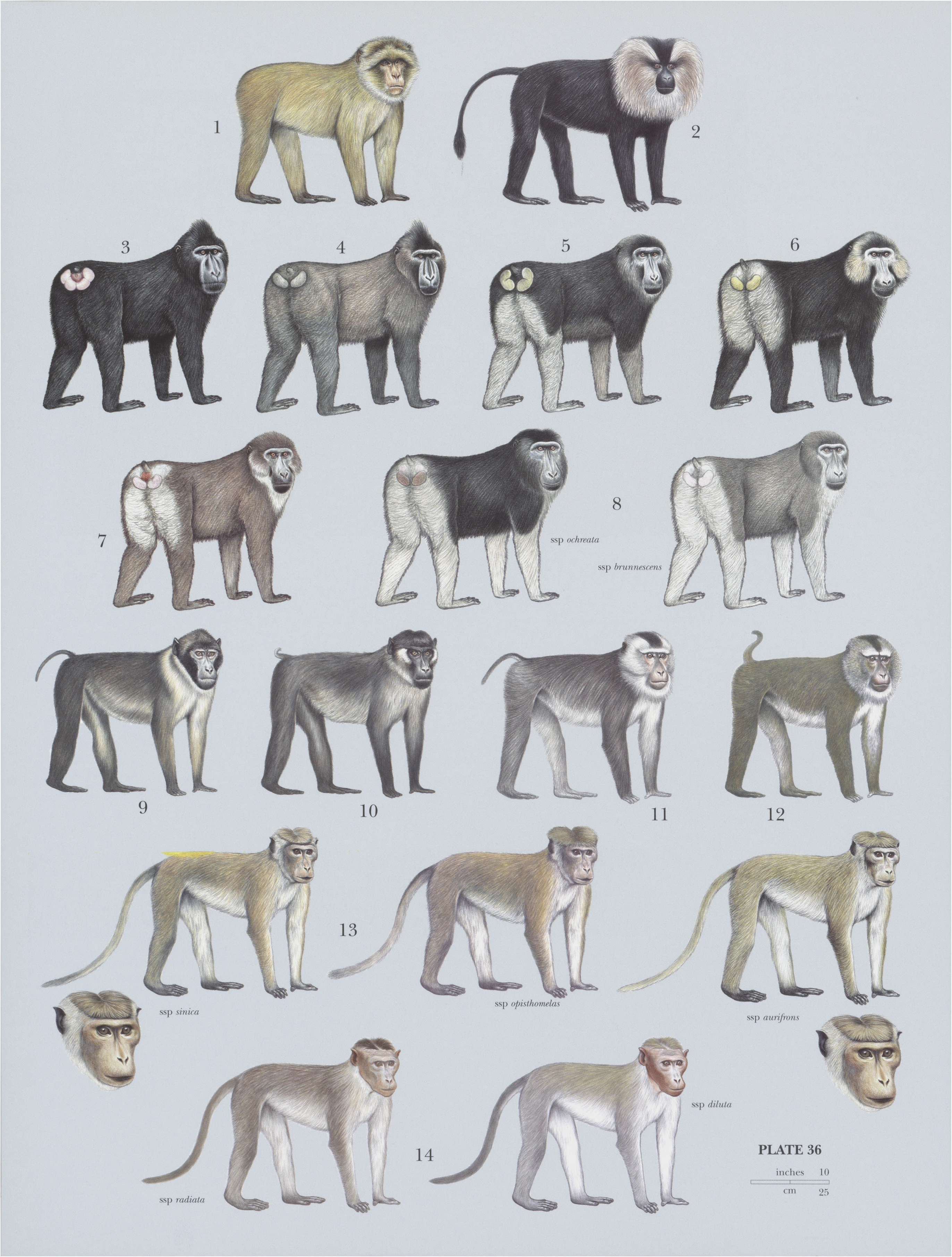

3. View Plate 36: Cercopithecidae

Crested Macaque

French: Macaque noir / German: Schopfmakak / Spanish: Macaco crestado

Other common names: Black Crested Macaque, Celebes Black Ape, Celebes Black Macaque, Celebes Crested Macaque, Celebes Macaque, Sulawesi Black Macaque, Sulawesi Crested Black Macaque

Taxonomy. Cynocephalus niger Desmarest, 1822 ,

“One of the islands of the Indian Archipelago.”

In his 1969 review of the Sulawesi macaques, J. Fooden classified the distinct taxa as full species because he had then no evidence of intergradation. In 1980, C. P. Groves reported on a zone of intergradation between M. nigra and M. nigrescens in the downstream region of the Onggak Dumoga River, and he placed nigrescens as a subspecies of nigra . This classification was followed G. Corbet and J. Hill in their review, The Mammals of the Indomalayan Region, published in 1992. The hybrid zone: is: restricted, however, and even though M. nigra and M. nigrescens are genetically quite similar, and morphologically more similar to each other than to other species, they are distinct and since 2001, Groves has classified nigra and nigrescens as separate species. M. nigra is a member of the silenus species group, including M. siberu , M. pagensis , M. leonina , M. nemestrina , M. silenus , and the other Sulawesi species. Monotypic.

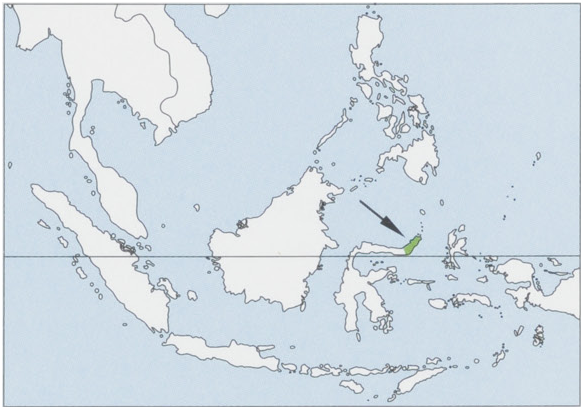

Distribution. N Sulawesi (E tip of the N peninsula), Manado Tua and Talise Is. Introduced into the Moluccas Archipelago (Bacan I). View Figure

Descriptive notes. Head-body 50-57 cm (males) and 44.5-55 cm (females), tail 1.5-2.5 cm; weight 10.2-13 kg (males) and 5.5-8 kg (females). Fur of the Crested Macaque is plain dark brown to blackish, as is the bare or short-haired facial skin. Infants are born with pinkish faces that turn black in the first months oflife. Hairs of the vertex are elongated (5-15 cm), forming an erectile crest. Ischial callosities are reniform, bright pinkish, and subdivided by a transverse furrow; in contrast, they are gray and form an elongated oval in the Gorontalo Macaque ( M. nigrescens ). The skull exhibits strongly developed supramaxillary ridges that are most pronounced in adult males. Posterior roots of these ridges are broadened and elevated, which gives the face of the male Crested Macaque a distinct appearance among the Sulawesi macaques (but see the Gorontalo Macaque). Male scrota and anuses have a red coloration, which has never been described for other Sulawesi macaques but may exist in at least some of them (e.g. Moor Macaque, M. maura ). The Gorontalo Macaque differs from the Crested Macaque in its general body color being medium to dark brown, and its head, arms, legs, and ventral surface being black, contrasting with the color of the body. They are the same color in the Crested Macaque.

Habitat. Lowland and montane primary rainforests. Due to increased pressures of habitat destruction, Crested Macaques are also found in secondary forests, actively logged forests, and grassland and cultivated land if they are surrounded by primary forest.

Food and Feeding. Crested Macaques have a diverse diet but mainly feed on fruits (66% of feeding bouts) and invertebrates (32% feeding bouts). A minor part of their diet consists of vegetative plant material and small vertebrates such as frogs, lizards, snakes, and bats. Because of the destruction of their natural habitat, Crested Macaques may invade plantations and feed on coconuts, mangos, sugar palm sap, and other crops.

Breeding. Although Crested Macaques give birth throughout the year, they show an intermediate degree of reproductive seasonality with more than three-quarters of births occurring within seven consecutive months (December—June). In the wild, females usually undergo several ovarian cycles before conceiving. Cycles are relatively long, lasting on average 39-6 days. In captivity, they even extend over this period if males are not available. During ovarian cycles, female Crested Macaques exhibit a pronounced swelling of their anogenital tissue, which is a good indicator of the timing of ovulation. Fully turgescent females are usually mate-guarded by high-ranking males, but they still manage to mate with other males to a minor extent. During mating, females may utter copulation calls, but the frequency and loudness of calls vary between females and between cycles of the same female. Similar to anogenital swellings, female copulation calls, if uttered, also provide a hint to the likelihood of ovulation. Male Crested Macaques may vocalize during copulation, but the function of these calls remains unknown. Similar to most of the other anthropoid primates, females do not show any post-conception mating. Infants are born after a gestation of 175 days, and females give birth only every other year. The interbirth interval is 22 months.

Activity patterns. Crested Macaques are mainly terrestrial, spending 60% of their time on the ground where they prefer to travel and rest. Most of the day, they occupy themselves moving, foraging, and feeding. Still, one-quarter of their time is spent on social activities, mainly grooming. A lot of the resting and social time takes place during midday. During extreme seasons, Crested Macaques travel less and spend more time resting and socializing on the ground, probably as an adaptation to the heat.

Movements, Home range and Social organization. Crested Macaques live in multmale—multifemale, female philopatric groups, which are, in contrast to other Sulawesi macaques, quite large. Groups comprise 60-80 individuals (adult sex ratio: 1:2-9), but they can grow up to more than 100 individuals. Smaller groups of only 25 individuals have also been observed. Home range size is 74-350 ha depending on group size and time of the year; home ranges are bigger during the rainy season. Home ranges of adjacent groups overlap significantly. Among macaques, Crested Macaques are among those that are the most socially tolerant, with conflicts being of lower intensity, often bidirectional and commonly reconciled. In contrast to more despotic species, female Crested Macaques often exchange affiliative interactions across matrilines. Males, however, fight fiercely over rank and can receive severe injuries. A typical demonstration of male social status is the loud call, which is emitted by all adult group males but significantly more often by high-ranking ones. Male dominance statusis also encoded in the acoustic structures of their loud calls. The red of the male’s scrotum and anus varies in intensity among individuals but also over time in the same individual. It also seems to be a sexual signal, but its precise function still remains unexplained. The extent of the red increases with male age. Males move several times between groups and also have been found roaming the forest solitarily or in small all-male groups. They emigrate from their natal group when reaching adulthood, often immediately trying to take over top dominance in neighboring groups.

Status and Conservation. CITES Appendix II. Classified as Critically Endangered on The IUCN Red List. The Crested Macaque is the most threatened of the seven species of macaques endemic to the island of Sulawesi. Crested Macaques have suffered severe hunting pressure and a widespread decline of their habitat. Consumption of monkeys and other wildlife is a longstanding tradition in ethnic groups of north-eastern Sulawesi and may have originally been sustainable. The human population in the area has substantially increased over the last decades, however, boosted by transmigration within Indonesia. This has increased hunting and led to the widespread conversion of rainforests for agricultural land and infrastructure. Legal and illegal logging and mining add to the rapid shrinking and fragmentation of natural forests, with an unknown effect on the separated small macaque populations remaining. Bushmeat hunting is not sustainable anymore and causes the rapid decline of all wildlife and, in particular, macaques. Tangkoko Batuangus Nature Reserve, although only ¢.3600 ha, seems to be the home of the largest population of Crested Macaques within its native distribution. Nevertheless, recent surveys suggest that the population in this protected area has suffered a decline of almost 85% since 1978. Current conservation and research activities, therefore, specifically focus on this population. A more viable population of Crested Macaques inhabits the island of Bacan, North Moluccas, where they have been introduced by humans. Given food taboos of the island’s people, the survival of this population may be better secured. The conservational value of the Bacan macaques is debatable because the island was not part of the species’ original distribution and, more importantly, the small founder population can be expected to have limited genetic variability.

Bibliography. Bernstein et al. (1982), Bynum (1999), Bynum et al. (1999), Duboscq et al. (2013), Fooden (1969), Gallardo et al. (2012), Groves (1980, 2001), Higham et al. (2012), Lee, R.J. (1995, 1999, 2000), Lee, R.J. & Kussoy (1999), Lee, R.J. et al. (2005), Melfi (2010), Micheletta et al. (2012), Neumann et al. (2010), O'Brien & Kinnaird (1997), Reed et al. (1997), Rosenbaum etal. (1998), Thierry (2000b, 2007, 2011), Watanabe & Matsumura (1991).

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.