Andinobates cassidyhornae, Amézquita, Adolfo, Márquez, Roberto, Medina, Ricardo, Mejía-Vargas, Daniel, Kahn, Ted R., Suárez, Gustavo & Mazariegos, Luis, 2013

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/ 10.11646/zootaxa.3620.1.8 |

|

publication LSID |

lsid:zoobank.org:pub:93F67C5A-1636-4F4A-9980-0BFBC82B5441 |

|

DOI |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.5659304 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/D47487C6-FFD0-9966-FF5E-FF0AFCC48285 |

|

treatment provided by |

Plazi |

|

scientific name |

Andinobates cassidyhornae |

| status |

sp. nov. |

Andinobates cassidyhornae View in CoL sp. nov.

Dendrobates opisthomelas Silverstone 1975 . Quebrada Arriba, bus stop 10 km by road from town of Andes, mountains near road (LACM 71962-70).

Andinobates opisthomelas Brown & Twomey et al. 2011 . pp 33 Plate 3, Figure O. Guatapé Antioquia, Colombia, because of a mistake in the final manuscript. The correct locality according to one of the authors of that paper (D.M.-V.), who actually took the photograph, is Carmen de Atrato, Chocó, Colombia.

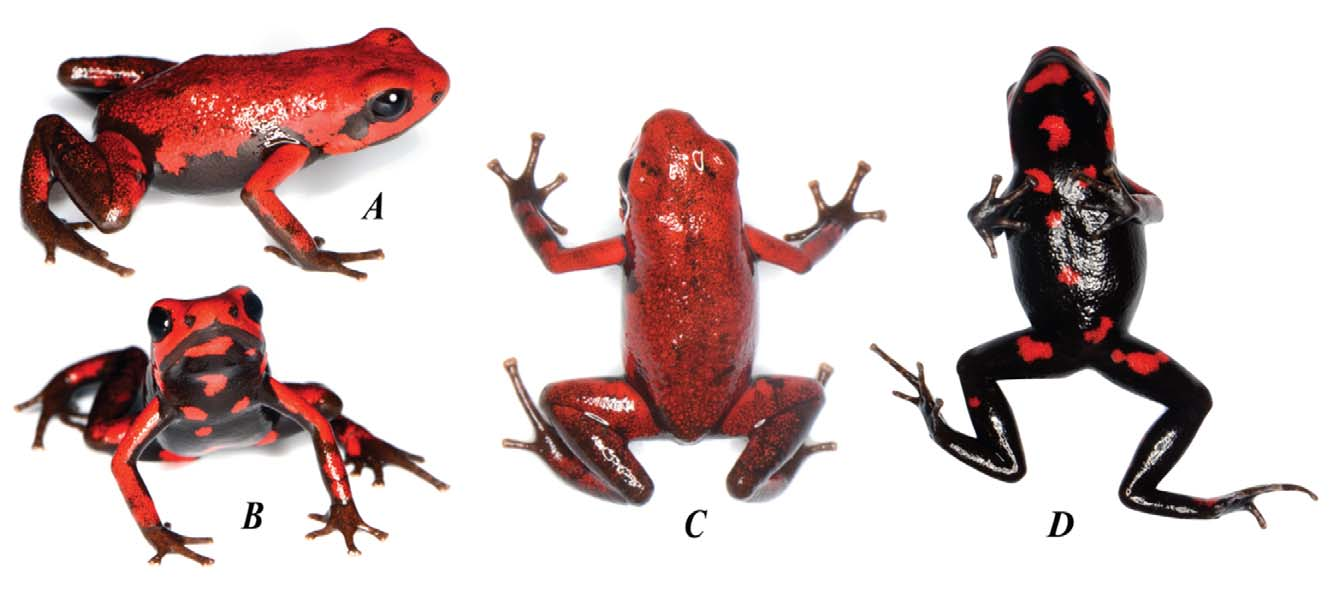

Holotype: An adult female ( Figure 2 View FIGURE 2 ) deposited in the amphibian collection of the Universidad de los Andes, Bogotá, Colombia, Andes-A1095 (Field number LUMA1001) is one of a series collected on March 30th 2012 at the Mesenia-Paramillo Nature Reserve, Municipality of Andes, Department of Antioquia, Colombia, by R. Medina, G. Suárez & L. Mazariegos.

Paratypes: Four adult females, and two adult males (Andes-A 1088–1091, and 1093–1095) collected by R. Medina, G. Suárez & L. Mazariegos. Locality data is the same as the type locality (see below).

Type locality. Mesenia-Paramillo Nature Reserve, Vereda La Mesenia, about 12 km south of the municipality of Jardín but politically within the Municipality of Andes, (both in Departamento de Antioquia, Colombia), ca 5° 31´N, 75° 53´W at 2000 m elevation. Because of the heavy smuggling on dendrobatid frogs we refrain from providing more accurate coordinates.

Etymology. This specific epithet cassidyhornae is a patronym in honor of Cassidy Horn, for her passionate interest in poison frogs and her generous contributions to the conservation of cloud forests in Colombia.

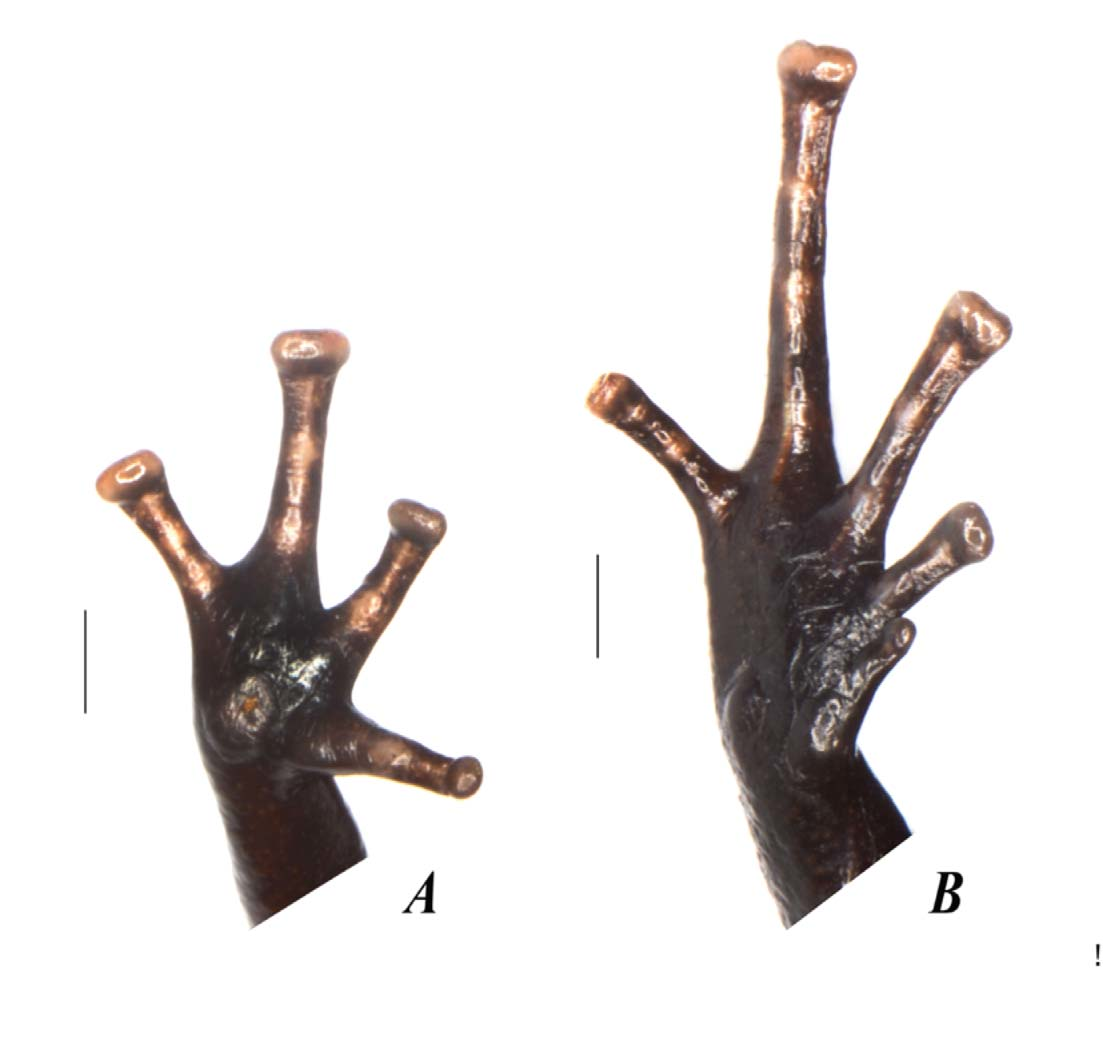

Definition and diagnosis. A small-sized dendrobatid frog that we assign to the Andinobates bombetes species group (Brown & Twomey et al. 2011) based on the phylogenetic affinity (see Molecular and Phylogenetic Analyses) and on the following morphological characters: adult snout-vent length (SVL) <20.0 mm; adults with bright dorsal coloration; ventral coloration variable, usually with distinct bright markings; colored throat patch absent; head narrower than body; teeth absent; vocal slits present in males; first finger distinctly shorter than second ( Figure 3 View FIGURE 3 ); finger discs II and III weakly to moderately expanded; toe disc III and IV weakly expanded; toe V unexpanded; toe webbing absent; median lingual process absent (Brown & Twomey et al. 2011).

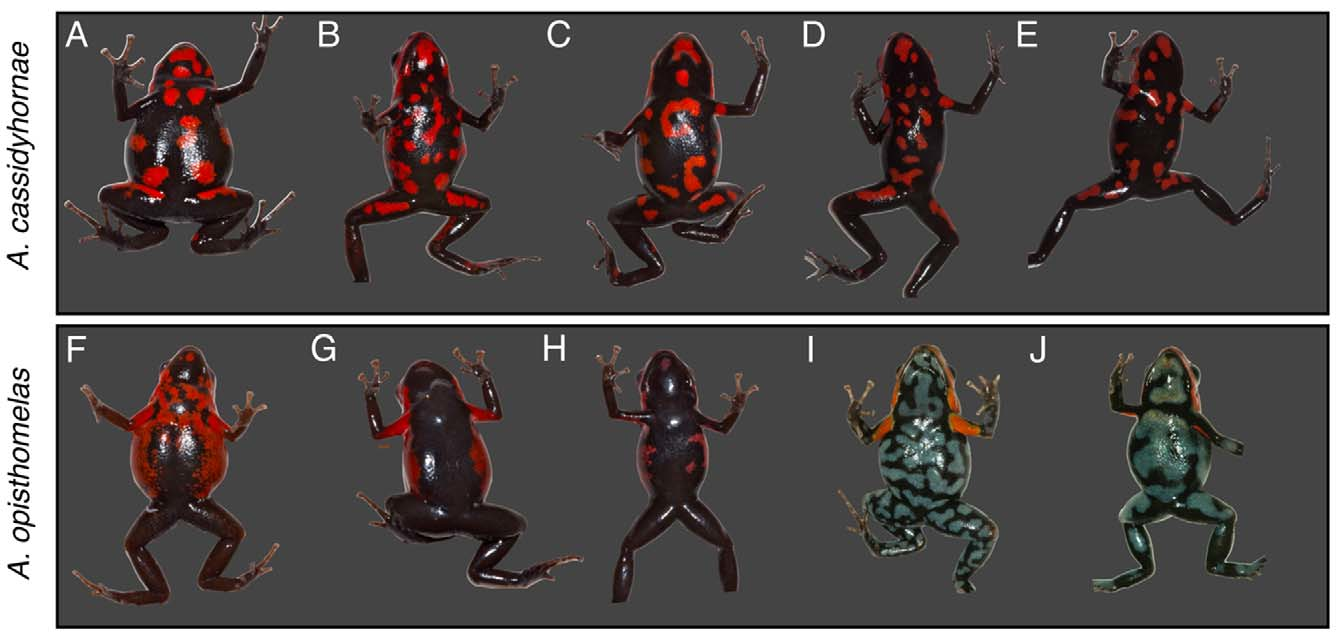

Andinobates cassidyhornae sp. nov. has an SVL of 19.03± 0.31 mm (mean±SD, N = 12 frogs), a bright red dorsum with the color extending onto the upper front and hind limbs; lower forearms and hind limbs are dark brown. Ventral coloration is black with bright red irregularly sized and spaced ovoid or ‘comma’ shaped blotches or spots. It can be externally distinguished from other species in the bombetes group by the distinctive color pattern: in A. cassidyhornae dorsum is bright red, and venter is black with well-defined bright red blotches or spots ( Figure 4 View FIGURE 4 ) vs. (1) in A. opisthomelas dorsum is red often with a posterior suffusion to brown, and venter is black with numerous white spots or reticulation (white-venter form) or venter is chocolate brown sometimes with red suffusion from the flanks (brown-venter form); (2) in A. virolinensis venter is whitish or bluish with black reticulation; (3) in A. bombetes the anterior half of dorsum exhibits bright red, yellow or rarely orange longitudinal and broad dorsolateral stripes; (4) in A. tolimensis the head is yellow, fading to brown towards the dorsum; (5) in A. dorisswansonae the dorsum is black or brown with red blotches, and the venter entirely black or black with few white or yellowish blotches; and (6) in A. daleswansoni the head is entirely red, and the body dull gold or brown.

Measurements of the holotype (mm). The holotype measurements correspond to an adult female with a SVL of 18.99 mm; TL of 8.10; HaL of 4.58; HL of 4.85; HW of 6.29; GBW of 7.54; IOD of 2.31; HDT of 1.23; ED of 2.15; TSCN of 1.40; NED of 1.52; IND of 2.36; MTD of 0.75; W3FD of 0.78; W3F of 0.46; W3TD of 0.83; W3T of 0.47; W4TD of 0.87; and W4T of 0.49. The corresponding measurements of all specimens collected are shown in Table 2.

Measurements Andes- Andes- Andes- Andes- Andes- Andes- Andes- Median SD

A1093 A1088 A1089 A1090 A1094 A1091 A1095

SVL 19.36 19.34 19.17 18.92 18.45 18.99 18.99 18.99 0.31 TL 8.59 8.52 8.23 8.51 8.50 8.66 8.10 8.51 0.20 HaL 4.59 4.67 4.67 4.60 5.14 4.91 4.58 4.67 0.21 HL 6.06 5.59 5.17 4.75 5.09 5.00 4.85 5.09 0.46 HW 5.38 5.99 5.94 5.75 6.20 5.90 6.29 5.94 0.30 GBW 8.50 8.85 8.13 7.11 7.56 7.20 7.54 7.56 0.66 IOD 2.38 2.30 2.12 1.85 2.26 2.14 2.31 2.26 0.18 HTD 1.41 1.17 0.98 0.96 1.05 0.97 1.23 1.05 0.17 ED 2.49 2.31 2.12 2.45 2.47 2.21 2.15 2.31 0.16 TSCN 1.78 1.34 1.26 1.22 1.54 1.35 1.40 1.35 0.19 NED 1.71 1.68 1.54 1.57 1.78 1.68 1.52 1.68 0.10 IND 2.47 2.33 2.32 2.42 2.84 2.56 2.36 2.42 0.18 MTD 0.84 0.72 0.67 0.60 0.89 0.91 0.75 0.75 0.12 W 3FD 0.94 0.99 0.85 0.95 1.12 1.10 0.78 0.95 0.12 W 3F 0.49 0.44 0.48 0.53 0.65 0.52 0.46 0.49 0.07 Description of the holotype: The head is slightly wider than longer, and is narrower than the body. Snout subovoid in dorsal view and truncated in lateral view. Canthus rostralis subovoid, loreal region flat and vertical. Nares situated much closer to the end of the snout than to the eyes, ovoid in shape and directed posterolaterally. Eyes large and prominent with a diameter of 11.3% of SVL. The pupil is rounded and horizontally elliptical. Tympana and tympanic rings are in the posterolateral regions, ovoid and wider dorsoventrally, measuring 57.2 % of the diameter of the eyes. Supratympanic fold absent.

Rounded choanae, not visible in ventral view, as they are completely covered by the maxillary arch. Vomerine, maxillary and premaxillary teeth are absent. Tongue is elongated, almost two times longer than wide; the posterior margin of the tongue is not indented and its posterior third is not adhered to floor of mouth.

Hand relatively large ( Figure 3 View FIGURE 3 ), with a length equal to 24.1% of the snout-vent length. The relative length of the fingers in increasing order of size is: IV<II<I<III. The tip of the number IV digit reaches the middle of the second to last phalange of the number III digit and the distal extreme of the first digit reaches the base of the disc of the second digit. Finger discs moderately expanded on digits of the hand. Paired dorsal pads on dorsal surfaces of the discs are present. Outer metacarpal tubercle somewhat flat and rounded, inner metacarpal tubercles are elliptical and are located at the base of the first (I) fingers, basal subarticular tubercles are rounded and flat over fingers I and II. Two rounded and flattened subarticular tubercles appear on the number III and IV finger digits; the latter subarticular tubercle is not pronounced ( Figure 3 View FIGURE 3 ).

The relative length of the toes, in increasing size order is I<II<V<III<IV. The discs of toes are smaller than disks of fingers. Toes number II with the basal subarticular tubercle not protuberant. Toes III and V with two subarticular tubercles, and toes IV with three subarticular tubercles. Supernumerary plantar tubercles are absent. External metatarsal tubercle is smaller than the inner metatarsal tubercles ( Figure 3 View FIGURE 3 ).

Coloration of holotype in life: Iris very dark brown; almost indistinguishable from black pupil. Nares encircled by black; margins of upper and lower jaws are very dark brown; tympana are black. Dorsum primarily bright scarlet red, sharply defined along the margins with a few irregularly scattered black speckles and small irregular black markings; in other specimens, black marks may reflect attacks by predators and should therefore not be considered an element of the dorsal coloration. Flanks are red laterally and black ventrolaterally with no gradient merging of the two colors as is seen in A. opisthomelas . Venter ground color black with irregular sharply contrasting bright scarlet red irregularly shaped blotches or spots. Upper forelimbs bright scarlet red and tinged brown where the upper and lower colorations meet, with lower forearm dark brown below the elbow; wrists and hands brown with tips of toes and fingers beige. Thigh mostly red, irregularly speckled with brown; shanks mostly brown tinged with red irregularly ( Figure 2 View FIGURE 2 ).

Color in preservative (ethanol 70%): The dark brown and black colors turn dull black to dark olive in preservative. Discs and tubercules on hands and feet, pupil and cornea become grey or nearly white with time. The predominantly bright scarlet red dorsal coloration and ventral red blotches and spots turn metallic olive; pattern remains clearly distinguishable in preservative (ethanol 70%).

Natural history: The natural history of this species is poorly known. We found individuals in areas covered with a thick layer of leaf litter and where abundant refuges were available. Males call regularly from the leaf litter or hidden amidst tree roots, throughout the day but prominently between 10h–14h and after periods of rain. Most calling males were observed accompanied by a female. We also encountered several courting pairs during a visit in March and April 2012. Males carry 1–3 tadpoles ( Figure 5 View FIGURE 5 ) on their dorsum. Males of other species of the bombetes group are known to release their tadpoles in bromeliad water tanks. Some tadpoles of the new species were found in water within the inflorescence husks of Wettinia palms. Whether this species displays biparental care is unknown.

Molecular and phylogenetic analyses. The final alignment consisted of 1119 bp (700bp unambiguously aligned from the Cytb gene and 419bp from the 16S gene). The chosen partitioning strategy was as follows: 16S unpartitioned under the GTR+ Γ model, and Cytb partitioned by codon position with K80+I, HKY+I and GTR+ Γ for the first, second, and third positions, respectively. Both ML and Bayesian phylogenies placed A. cassidyhornae sp. nov. as an independent, well-supported clade, separate from other species, within the bombetes species group. The two sequenced populations, the white- and the brown-venter forms, of A. opisthomelas formed a monophyletic albeit poorly supported group ( Figure 6 View FIGURE 6 ). The topology obtained is roughly consistent with the results of Brown & Twomey et al. (2011), but changes the relationships between A. virolinensis , A. tolimensis and A. bombetes , placing the first two as reciprocally monophyletic clades, and A. bombetes as the sister group of the two. However, the deeper phylogenetic relationships between the species in this group still require further study, since the obtained topology is highly polytomic and not well supported at this level. Within A. cassidyhornae sp. nov., individuals from the Mesenia-Paramillo Natural Reserve, Antioquia, cluster together in a monophyletic group, whereas individuals from other localities do not show evidence of genetic structuring.

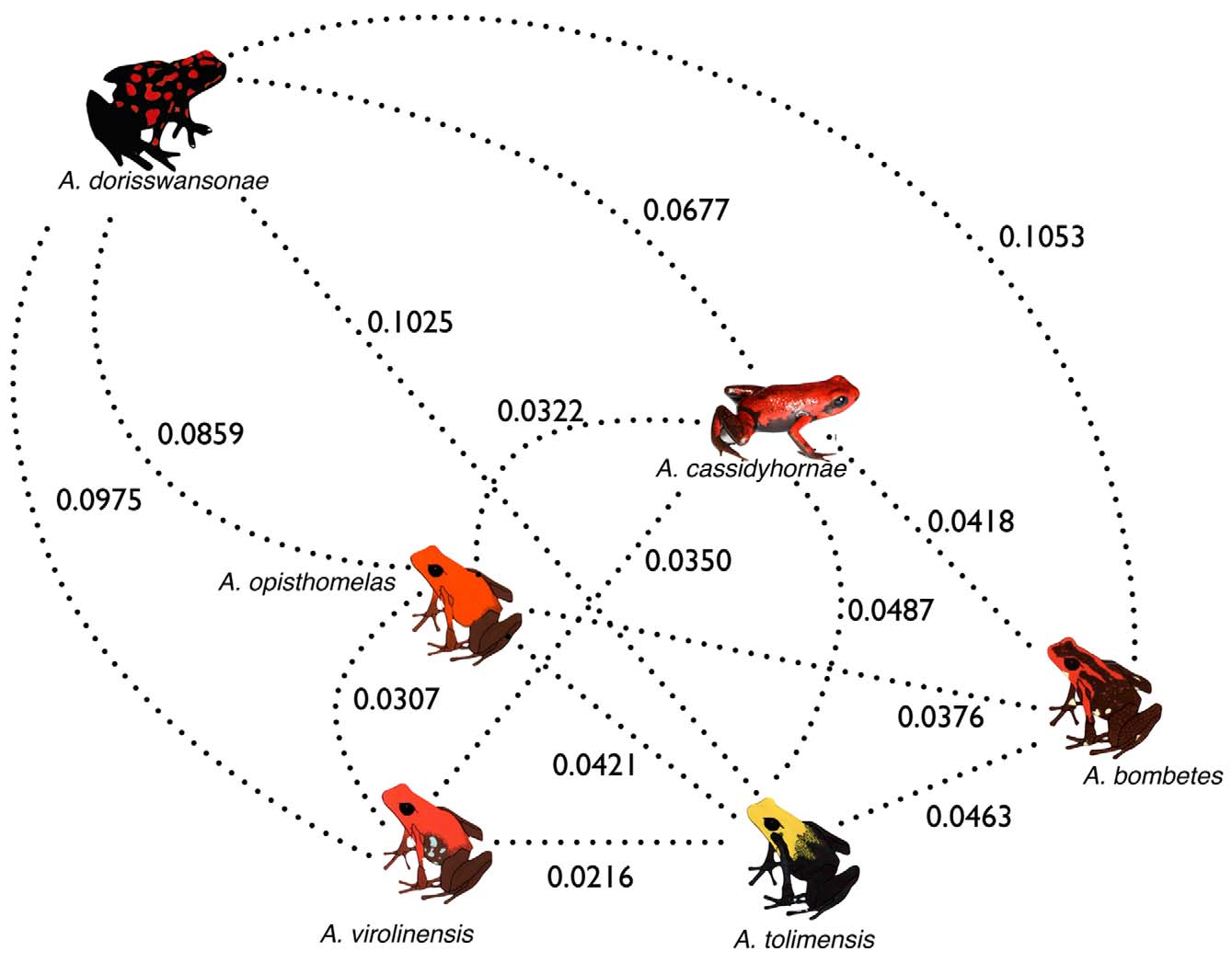

The SH tests rejected, at a very high level of statistical significance, two out of the three null topologies (H0) that placed A. cassidyhornae sp. nov. within a clade with A. opisthomelas (P <0.00001), with A. virolinensis (P <0.00001), and with A. bombetes (P = 0.05134). Additionally, pairwise genetic distances (K2P) between A. cassidyhornae sp. nov. and other species within the bombetes species group ranged between 0.0320–0.0677, well within the range of interspecific distances ( Figure 7 View FIGURE 7 ) observed for the group (0.0216–0.1053), and about tenfold the intraspecific distances observed (0–0.0091). Altogether, the reconstructed phylogenetic tree, the topology (SH) tests, and pairwise genetic distances offer strong support for A. cassidyhornae sp. nov. being a distinct species within the bombetes species group.

Bioacoustic analyses. All species’ calls within the Andinobates bombetes species group consist of long and atonal series of pulses sounding like a ‘buzz’ or rattle, which is often longer than 1 sec. The advertisement call of A. cassidyhornae sp. nov. ( Figure 8 View FIGURE 8 ) follows roughly the same pattern. Calls consist of 234.3±20.3 (mean±SD) pulses, last 1.94± 0.26 s, and are often uttered as series of calls separated by regular silent intervals of 10.1± 2.1 s. The rise time is 50.0±13.2 % of the call duration. The peak call frequency averages 4.32±0.14 kHz and the frequency bandwidth 0.81±0.40 kHz.

Combining the calls of A. cassidyhornae sp. nov., A. opisthomelas (two localities), A. bombetes , and A. virolinensis , we found that call duration (linear regression, R2=0.31, F=13.9, P=0.0008, N= 16 males), inter-call interval (R2=0.17, F=6.5, P=0.0162), and the number of pulses per call (R2=0.12, F=4.3, P=0.0472) decreased at higher temperatures. After removing the temperature effect by calculating regression residuals, the calls of A. cassidyhornae sp. nov. were clearly separated from the calls of the other species in a two-dimensional discriminant space ( Figure 9 View FIGURE 9 , above, discriminant analysis, Wilks’ Lambda approxim. F=13.9, P<0.0001). The first discriminant axis accounted for 87.7 % of variation and separated very well the calls of A. cassidyhornae sp. nov. from the call of any other species because the former were lower in peak frequency (F to enter=39.6, standardized discriminant coefficient=1.10, P<0.0001). The second discriminant axis accounted for 10.1% of variation and separated the calls of A. cassidyhornae sp. nov. from the call of A. bombetes because the former were longer in duration (F to enter=6.9, standardized discriminant coefficient=0.97, P=0.0013).

Regarding pairwise species comparisons by univariate ( Figure 9 View FIGURE 9 , below) tests, the advertisement call of A. cassidyhornae sp. nov. was lower in peak frequency than the call of A. opisthomelas (Tukey-Kramer HSD test, - 0.97 kHz, P<0.0001), A. virolinensis (- 0.71, P<0.0001) and A. bombetes (- 0.53, P<0.0001). It was also longer in duration (+ 0.55 s, P=0.0058) and consisted of more pulses (+ 48 pulses, P=0.0356) compared to A. bombetes . Finally, its frequency bandwidth was wider compared to A. virolinensis (+ 0.40 kHz, P=0.0220) and A. opisthomelas (+ 0.35 kHz, P=0.0246).

The strong among-species variation in call peak frequency could be partly attributed to concomitant variation in body size. Larger frogs usually produce calls at lower frequency values (e.g. Erdtmann & Amézquita 2009 for dendrobatid frogs) due to allometric constraints in larynx size. Indeed, increasing peak frequency is roughly related to decreasing body size in our study species: A. cassidyhornae sp. nov. is the largest species (mean±SD, 18.73± 0.22 mm, N = 5 recorded males, this study), followed by A. bombetes (17.76±0.55, N = 28 males, Myers & Daly 1980), A. opisthomelas (16.80±1.24, N = 26 males, Silverstone 1975), and A. virolinensis (16.72±0.54, N = 127 males, Valderrama-Vernaza et al. 2009). We did not correct for body size effects on peak frequency, because we did not have all information on body size of recorded individuals. In any case, the difference in call frequency alone probably has important evolutionary implications. Across many frog species, ear sensitivity appears to match the peak frequency of the advertisement call (Capranica & Moffat 1983, see Amézquita et al. 2006, 2011 for examples on dendrobatid frogs). Thus, among-lineages differences in call frequency would imply a frequency mismatch between senders and receivers in the mate recognition signal, which could have promoted reproductive isolation between any pair of the Andinobates species we studied here.

Distribution, habitat and ecology. At the type locality, the Mesenia-Paramillo Natural Reserve, Andinobates cassidyhornae sp. nov. was found in two fragments of heavily disturbed cloud forests. The approximately 1.52 hectare site is located on a steep montane slope with a gradient of 65% ( Figure 10 View FIGURE 10 ). This mountain forest fragment is entirely surrounded by cattle grazing grasslands and agriculture crops. The forest fragment there has a dense, sometimes broken canopy with a complex stratification and emergent trees up to 20 m in height. The dominant canopy trees are Lauraceae ( Nectandra acutifolia , Nectandra laurel , Aniba coto , Aiouea dubia , Aniba perutiles and Ocotea sp.), Oak ( Quercus humboldtii ) and Cedar ( Cedrela montana ). Shrubs and small trees in the families Ericaceae , Gesneriaceae , Melastomataceae , Piperaceae and Rubiaceae dominate the understory. Cyathea sp. tree ferns are common and epiphytes are dense on most trees dominated by the families Araceae , Bromeliaceae , Dryopteridaceae and Orchidaceae . Bromeliads are predominantly of the genus Guzmania . The forest floor is covered with abundant leaf litter and decomposing wood. Remains of inflorescences of Wettinia kalbreyerii palms are common, and serve as terrestrial water reservoirs for extended periods of time. Near daily (primarily evening and early morning) cloud cover of fog, mist and precipitation provide a very cool and humid mesic environment. No additional water sources, i.e. streams or springs were found there. The average annual rainfall is 2500 mm. The average annual regional temperature is 15.0° C. There are two conspicuous wet seasons beginning in March and lasting until May, and another extending from October through December. The species is also known from other three localities visited by one of the co-autors (D. M.-V., Figure 1 View FIGURE 1 ) that are much less known than the type localitity. They, however, look roughly similar in topography and frogs’ microhabitat.

Conservation status. Almost all the known localities for species in the A. bombetes group are within the 1200–2100 m elevational belt. In Colombia, the forests within this range have been severely degraded by intensive agriculture, remarkably coffee plantations, which is a first order national product. Andinobates cassidyhornae sp. nov. was found at four localities within 1800–2059 m elevation ( Figure 1 View FIGURE 1 ). The minimum area of the elevational range encompassing these localities, equivalent to the area achieved by the sum of the occupied grid squares ( Figure 2 View FIGURE 2 C in IUCN 2001), is between 200–300 km 2. However, to the best of or experience, the species distribution is sparsely patched including just few of the apparently suitable hills, probably occupying a minor fraction of the available habitat. In addition, most of the suitable forest below 2000 m elevation was cleared since many years ago at the type locality, which further limits the potential distribution of the new species.

Unfortunately, most localities included in this study are exposed to severe degradation by intensive agriculture. Contamination of watersheds by pesticides, herbicides, and soil degradation caused by agriculture and cattle grazing also degrade the environment here. At the type locality, there is an ongoing conservation project that involves the local community neighboring the Mesenia-Paramillo Nature Reserve and The Hummingbird Conservancy (THC) foundation. Based on their biogeographical, biological and hydrological importance, the project aims at increasing the percentage of protected conservation areas, thereby protecting from selective logging and massive deforestation, the old-growth cloud forests and sub-paramo ecosystems in the area.

Summing up, the long-term and immediate survival of this species is threatened by its apparently small distribution combined with the heavy disturbance of primary forests where it lives in. The species is also highly vulnerable to massive smuggling in short time spans, as typically occurs when new forms of dendrobatid frogs become known by the illegal pet market. Based on the available information, we propose at least temporarily listing A. cassidyhornae sp. nov. as Critically Endangered (A1c, B2bi, ii, iv, IUCN 2001). Further phylogenetic, biogeographic, and taxonomic studies are urgently needed to develop appropriate conservation strategies for this group of frogs. The information obtained would greatly assist in the development and implementation of a speciesspecific management plan for A. cassidyhornae sp. nov.

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.

|

Kingdom |

|

|

Phylum |

|

|

Class |

|

|

Order |

|

|

Family |

|

|

Genus |