Celestus Gray, 1839

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/10.11646/zootaxa.4974.2.1 |

|

publication LSID |

lsid:zoobank.org:pub:0CCA430E-5601-42CB-847F-87B22BFD3112 |

|

DOI |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.4891072 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/DA66BA10-FFCD-FFE0-0DF1-0E6A07C1D1A9 |

|

treatment provided by |

Plazi |

|

scientific name |

Celestus Gray, 1839 |

| status |

|

Genus Celestus Gray, 1839

Jamaican Forest Lizards

Figs. 10–14 View FIGURE 10 View FIGURE 11 View FIGURE 12 View FIGURE 13 View FIGURE 14

Celestus Gray, 1839:288 . Type species: Celestus striatus Gray, 1839:288 , by original designation.

Macrogongylus Werner, 1901:299 . Type species Macrogongylus brauni Werner, 1901:299 , by original designation.

Diagnosis. Species of Celestus have (1) claw sheath, absent, (2) contact between the nasal and rostral scales, absent, (3) scales in contact with the nasal scale, four, (4) postnasal scales, one, (5) position of the nostril in the nasal scale, central, (6) keels on dorsal body scales, present or absent, (7) digits per limb, five, (8) longest toe lamellae, 10–23, (9) dorsal scale rows, 82–140, (10) relative head width, 11.8–20.0, (11) relative rostral height, 47.6–66.5, (12) relative frontonasal length, 2.12–3.94, (13) relative interparietal distance, 0–0.953, (14) relative axilla-groin distance, 60.9–66.3.

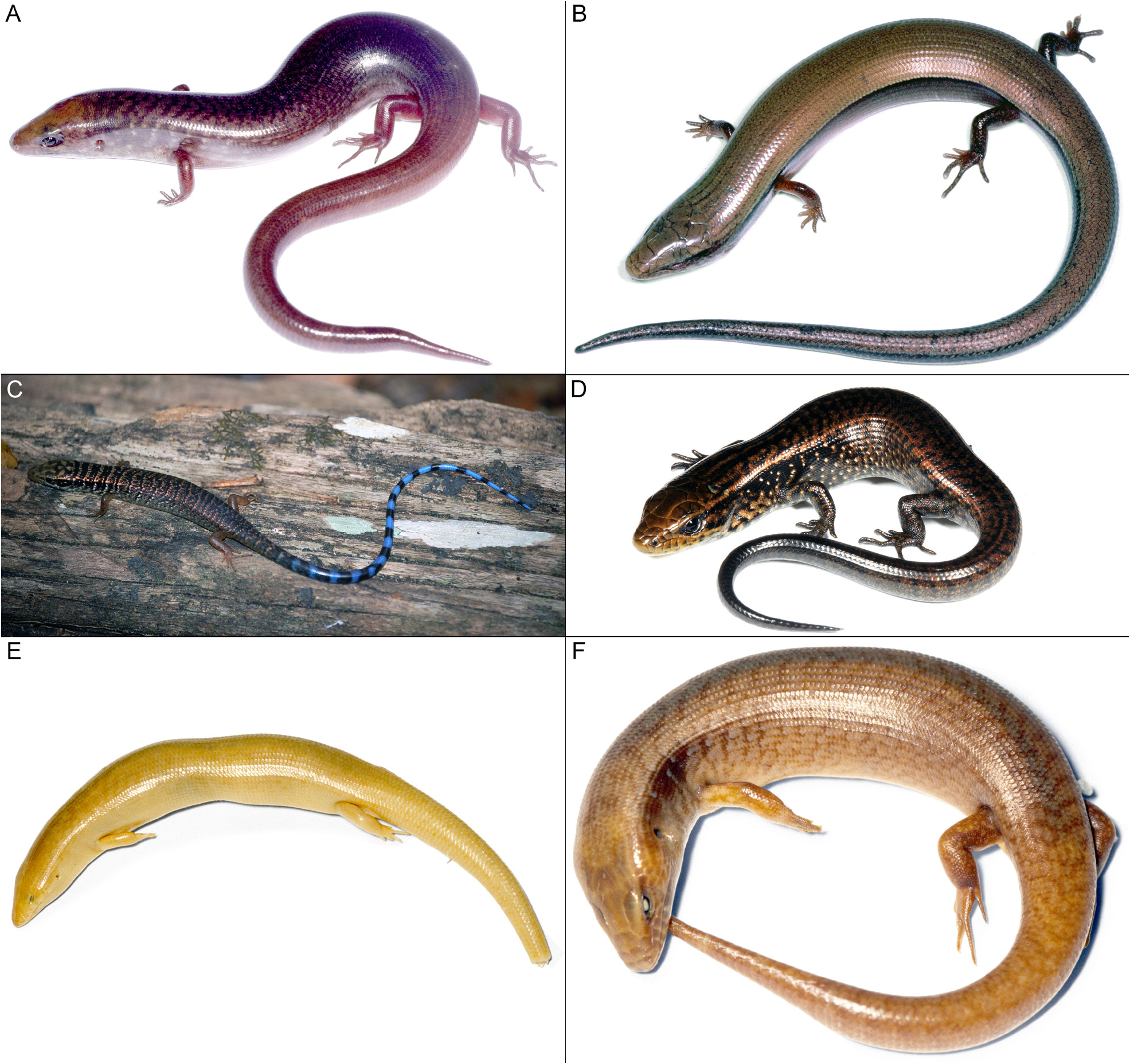

From Advenus gen. nov., we distinguish Celestus by the claw sheath (absent versus its presence in Advenus gen. nov.) and the relative axilla-groin distance (60.9–66.3 versus 60.0). From Caribicus gen. nov., we distinguish Celestus by the relative axilla-groin distance (60.9–66.3 versus 67.1–69.1). From Comptus gen. nov., we distinguish Celestus by the relative axilla-groin distance (60.9–66.3 versus 51.9–60.0). From Panolopus , we distinguish Celestus by the relative axilla-groin distance (60.9–66.3 versus 49.7–59.6). From Sauresia , we distinguish Celestus by the claw sheath (absent versus its presence in Sauresia ) and the digits per limb (five versus four). From Wetmorena , we distinguish Celestus by the absences of the claw sheath (versus its presence in Wetmorena ) and the digits per limb (five versus four).

Content. Eleven species ( Table 3 View TABLE 3 ): Celestus barbouri , C. crusculus , C. duquesneyi , C. fowleri , C. hewardii , C. macrolepis , C. macrotus , C. microblepharis , C. molesworthi , C. occiduus , and C. striatus .

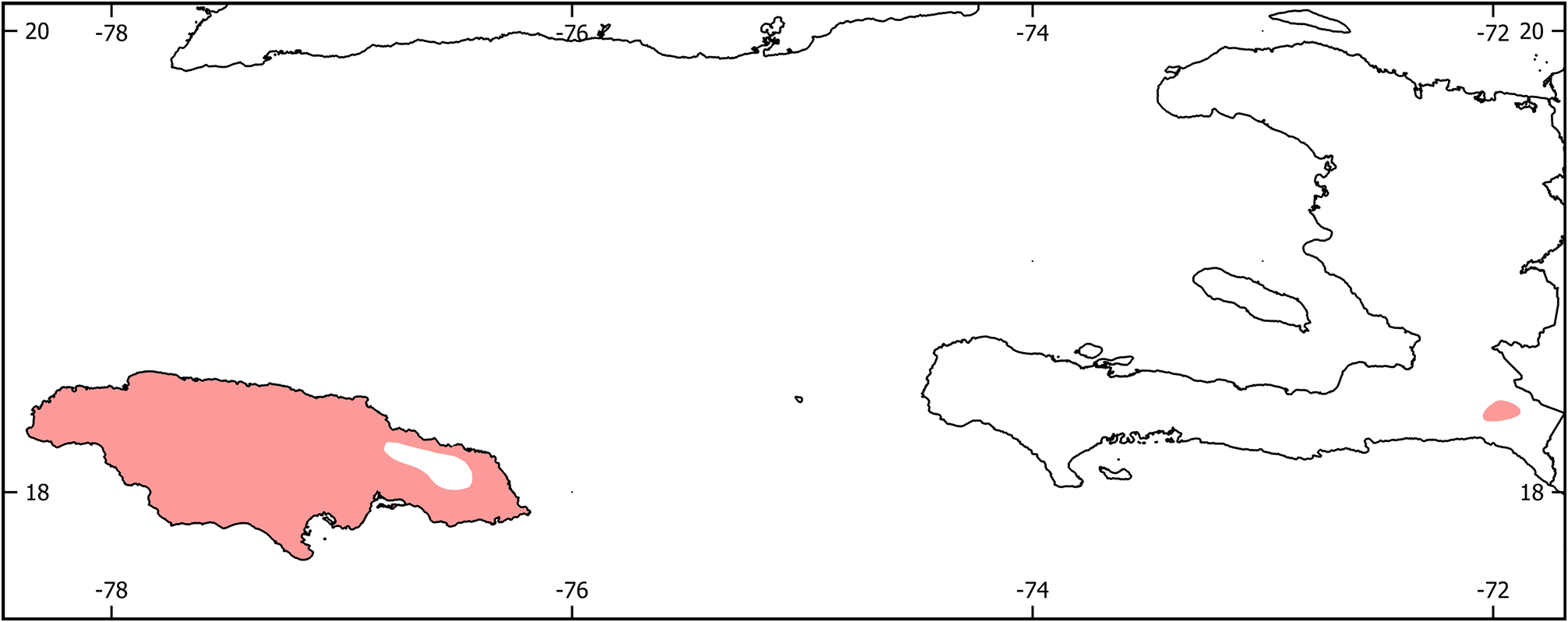

Distribution. Celestus occurs almost entirely on Jamaica, with a single species ( C. macrotus ) on Hispaniola ( Fig. 14 View FIGURE 14 ). The map does not include the distributions of Celestus macrolepis and C. striatus , which are unknown other than being restricted to Jamaica.

Etymology. Not defined in the original description, but a masculine noun probably from the Latin caelestis (heavenly), in reference to the “silvery” color of the type species noted by Gray (1839).

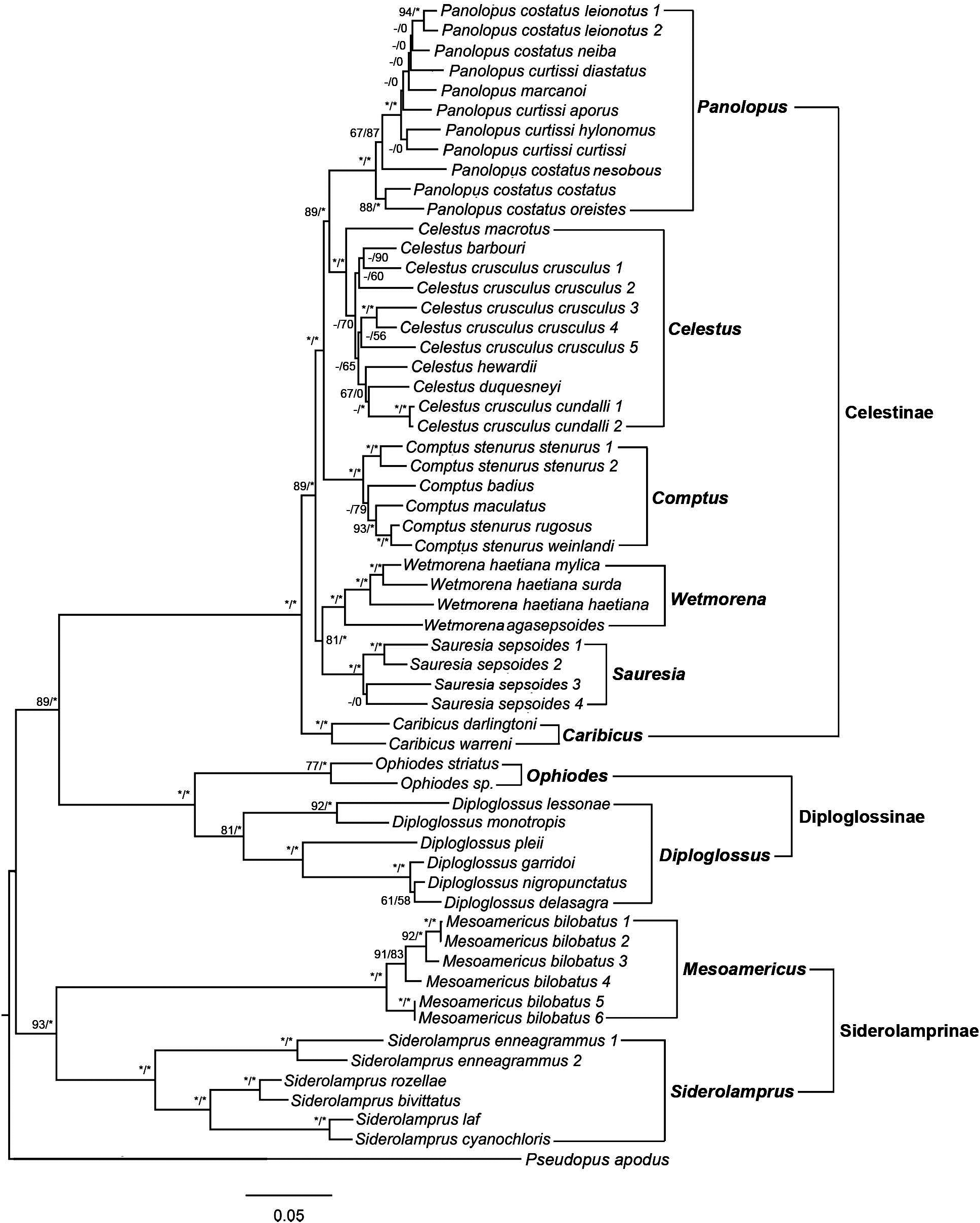

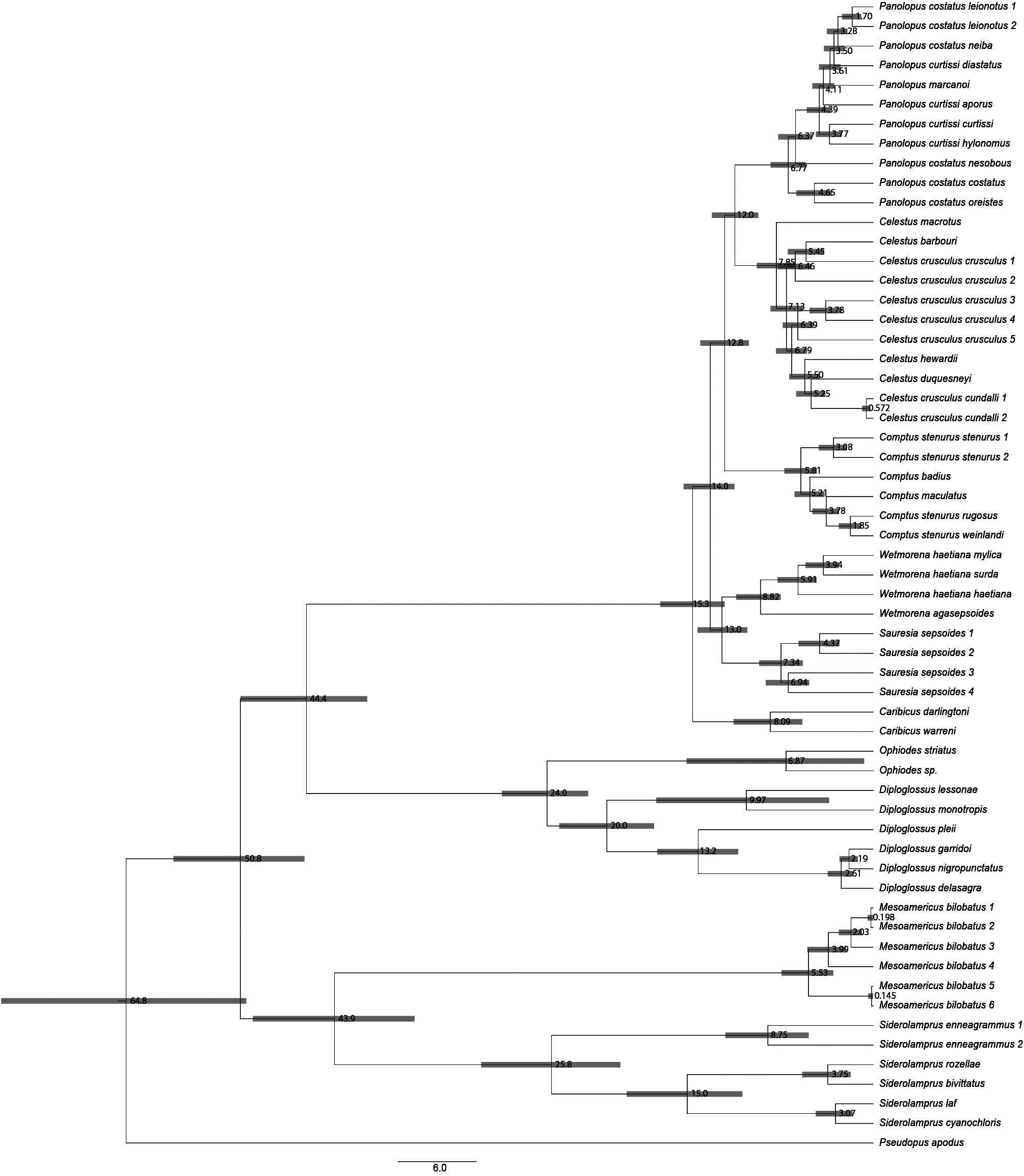

Remarks. Celestus is a monophyletic clade that has a support value of 100% in Bayesian and ML analyses ( Fig. 2 View FIGURE 2 ). Our phylogenies include five of the eleven species of Celestus ( Celestus barbouri , C. crusculus , C. duquesneyi , C. hewardii , and C. macrotus ). Our trees show that the two subspecies of Celestus crusculus ( C. c. crusculus and C. c. cundalli) are not related, indicating that cundalli warrants species recognition (Schools & Hedges, unpubl.). In addition, Celestus crusculus crusculus is not monophyletic and includes populations with deep divergences (3.7–6.7 Mya; Fig. 3 View FIGURE 3 ). These results, together with other molecular and morphological data, indicate that the genus Celestus includes at least six additional species (Schools & Hedges, unpubl.).

The origin and classification of Celestus striatus , the type species of the genus, are unresolved, even though the original describer indicated a general locality “West Indies” ( Gray 1845; Boulenger 1885). Schwartz (1964) examined photographs of the type of Celestus striatus and concluded that it was not from the Caribbean based on its large size ( 145 mm SVL), low midbody scale count (41) and, that it had three prefrontal scales—this latter condition being virtually unknown among West Indian taxa. Strahm and Schwartz (1977) “provisionally” considered C. striatus to be Central American based on its unusual scalation. Savage et al. (2008) did not examine the holotype of Celestus striatus but followed Schwartz’s (1964) characterization of its head scalation (one frontonasal and two prefrontals in the terminology of Savage et al.). However they did not readily accept a Central American origin for C. striatus , leaving its provenance a mystery.

One of us (S.B.H.) examined the type specimen of Celestus striatus in the Natural History Museum (London) and found that it is missing the frontonasal scale ( Fig. 11 View FIGURE 11 ). Instead, the underlying integument shows pseudosutures, which apparently led Schwartz to conclude, based on only a photograph, that there were three scales present instead of one, an easy error to make. We have available the photograph used by Schwartz and it shows the same pseudosutures, confirming that the specimen is missing the frontonasal scale. Boulenger (1885: pl. 16, fig. 1a) illustrated that specimen showing a single large frontonasal scale, apparently before it fell off. Now, with this correction, the head scalation is consistent with the notation by Gray (1845) that the specimen is from the “West Indies,” where a single large frontonasal scale is common.

Celestus striatus has all three diagnostic characters of the subfamily Celestinae ( Table 2 View TABLE 2 ). Within the Celestinae it differs from Advenus in lacking a claw sheath. Also, its combination of large size ( 144.5 mm SVL), high relative axilla-groin distance (89.0 mm = 61.6%), low midbody scale count, and high number of toe lamellae distinguish it from all genera in the family except Celestus , which is restricted to Jamaica and Hispaniola. The single species of Celestus in Hispaniola, C. macrotus , differs in many ways from C. striatus ( Table 2 View TABLE 2 ) and therefore Celestus striatus is most likely a Jamaican species, which also makes sense from historical considerations, in that Jamaica was the major British colony in the West Indies and source of BMNH herpetological specimens in the early 19 th century.

Barbour (1910) is one of the few researchers, besides us, to have considered that Celestus striatus is from Jamaica. He placed that species and C. hewardii in the synonymy of the Jamaican species C. occiduus . Both are diagnosable from C. occiduus , and most authors since have treated C. hewardii as a distinct species. However, after the status of C. striatus was placed in limbo following confusion over the frontonasal scale ( Schwartz 1964), the species became forgotten and was not listed in any major checklist or synthesis of West Indian herpetology, even as a synonym ( Schwartz & Thomas 1975; Schwartz & Henderson 1988; 1991; Henderson & Powell, 2009; Hedges et al. 2019). The Reptile Database ( Uetz et al. 2020) lists it as a synonym of the Hispaniolan species Comptus stenurus , from which it differs in many ways, as noted above. Also, Celestus striatus is an older name so it should not be a synonym of that species.

Celestus striatus differs from all other species in the genus by a combination of its large size, lack of a claw sheath, absence of a median keel on the dorsal scales, a high number of toe lamellae (24–26), a rounded tail (not laterally flattened as in C. occiduus ) and a pale (golden) coloration noted when it was described. The head shape is unusually flattened and the snout acuminate from above, resembling the head of the arboreal Jamaican species C. fowleri . That species differs from C. striatus by having a claw sheath but both are similar in their low midbody scale count and high number of toe lamellae, suggesting that they might be related and that C. striatus might be another arboreal species. Presumably, the introduction of the mongoose to Jamaica in 1872 ( Hedges & Conn 2012) either severely decimated C. striatus or caused it to go extinct. This is not unexpected considering that another Jamaican species, C. occiduus , has not been seen since the 19 th century, and several other Jamaican species are exceedingly rare, all attributed to the mongoose introduction ( Barbour 1910; Hedges & Conn 2012).

We also recognize Celestus macrolepis as a valid species. It was given that name because of the presence of a large, seven-sided frontonasal scale purportedly representing the unusual fusion of the internasals and frontonasal ( Gray 1845). One of us (S.B.H.) examined the holotype and it has the normal seven-sided frontonasal, not fused to the internasals ( Fig. 12 View FIGURE 12 ). The two (normal) pairs of internasals are present. The specimen agrees in other important details with the description by Gray, including its unique bi-colored pattern (see below), so there is no doubt that it is the same specimen that he described. Because the enlarged, seven-sided frontonasal of Celestus is unusual among lizards, it was an easy error to make. Boulenger (1885) placed Celestus macrolepis in the synonymy of C. occiduus and it has been largely forgotten for 136 years. Neither Barbour (1910, 1914) nor Grant (1940a) mentioned the species, but its position as a synonym of Celestus occiduus was noted more recently ( Schwartz & Thomas 1975; Schwartz & Henderson 1988).

The holotype of Celestus macrolepis ( Fig. 12 View FIGURE 12 ), 248 mm SVL, is surprisingly distinct from the similarly sized C. occiduus . It has a shorter, almost beak-like, snout and is mostly dark brown anteriorly (above and below) and paler posteriorly. The transition between the two colors is patch-like rather than gradual. A distinctive feature of scalation, noted by Gray (1845), is that the subocular scale is much smaller than in Celestus occiduus (and other species), barely pointed at the bottom, and does not protrude into the supralabial row. Celestus occiduus has a longer, more normal and slightly depressed (not beak-like) snout and a considerably larger subocular that protrudes into the supralabial scales. Other aspects of the head scalation also differ between the two species, as one would expect with such different head shapes. For these reasons, we consider Celestus macrolepis to be a valid species of Caribbean diploglossid lizard.

The holotype of Celestus macrolepis does not have a specific locality, only “West Indies,” but the body proportions (large, long legs) agree more with Jamaican species than other diploglossids in the West Indies. For example, the giant Caribicus of Hispaniola have distinctly smaller and shorter legs, and longer tails. Also, only two Jamaican species, Celestus occiduus and C. striatus , approach the high number (24) of 4th toe lamellae of Celestus macrolepis . Based on these morphological characteristics, we consider Celestus macrolepis to be endemic to Jamaica, and a species that may have occupied an ecological niche different from others. As with Celestus striatus , the introduction of the mongoose in 1872 may have driven C. macrolepis to great rarity or extinction.

With the addition of Celestus macrolepis , C. macrotus , and C. striatus , the newly restricted genus Celestus , which is almost exclusively a Jamaican radiation, now contains 11 species. However, the additional six species that warrant recognition (see above), mostly confused with what is now Celestus crusculus , will bring the total in Celestus to 17 species.

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.