Naja senegalensis, Trape, Jean-François, Chirio, Laurent, Broadley, Donald G. & Wüster, Wolfgang, 2009

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.190424 |

|

DOI |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.5631882 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/DB66570B-F261-FFC2-FF0F-3F87FE682775 |

|

treatment provided by |

Plazi |

|

scientific name |

Naja senegalensis |

| status |

sp. nov. |

Naja senegalensis sp. nov. Trape, Chirio and Wüster

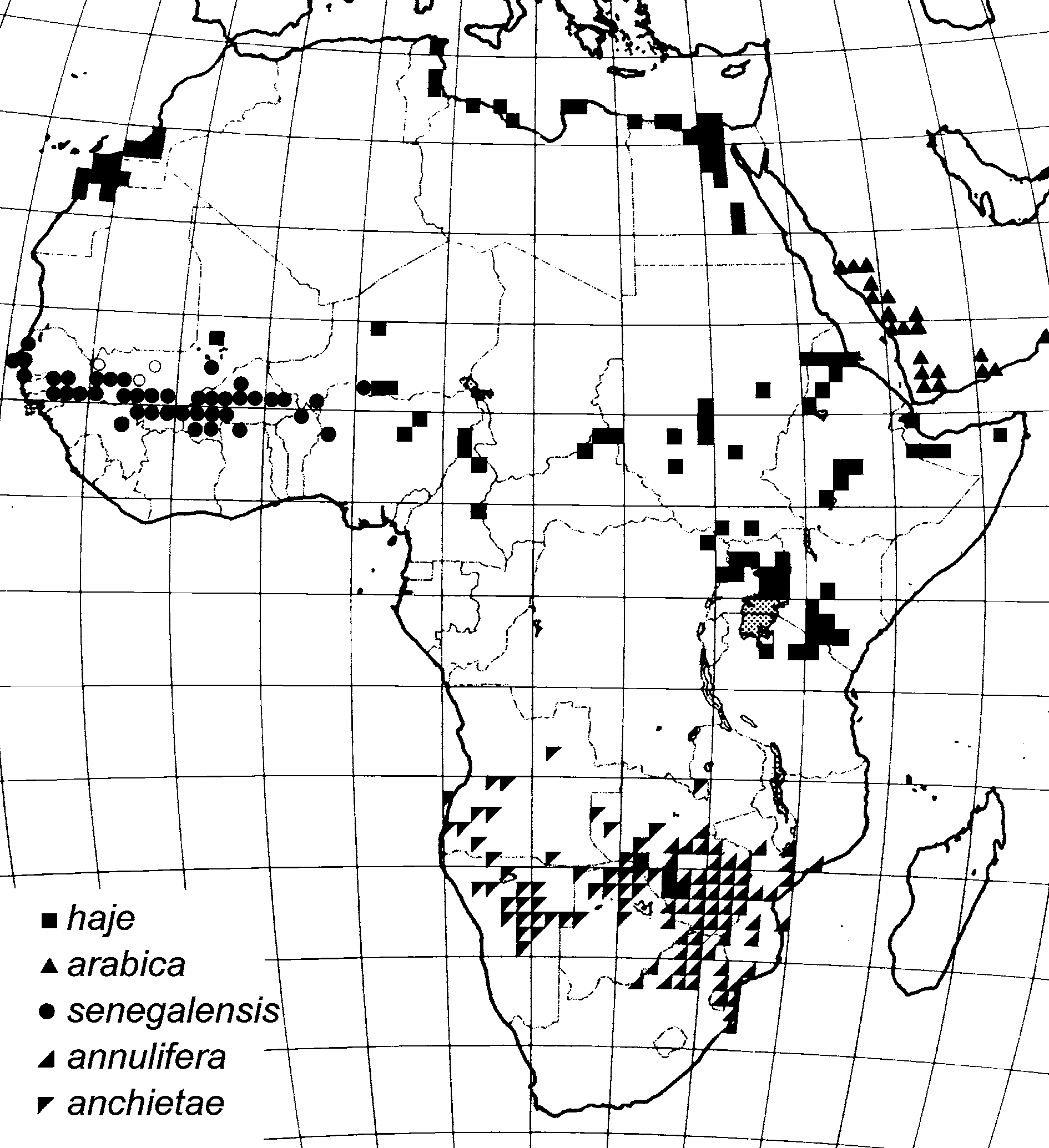

Figs. 4–8 View FIGURE 4 View FIGURE 5 View FIGURE 6 View FIGURE 7 View FIGURE 8

Holotype: MNHN 2008.0074 (previously IRD S-8549), collected in September 2008 near Dielmo ( 13°43’N, 16°25’W) by Mr. Babacar N’Dao, veterinary agent at Keur Lahim Fatim, who sent it to the first author ( Fig. 4–6 View FIGURE 4 View FIGURE 5 View FIGURE 6 ).

Paratypes: 31 specimens, all from Sénégal: MNHN 2008.0075 (previously IRD S-409), MNHN 2008.0076 (previously IRD S-1027) MNHN 2008.0077 (previously IRD S-1028), MNHN 2008.0078 (previously IRD S-1578), MNHN 2008.0079 (previously IRD S-1589): Keur Lahine Fatim ( 13°44’N, 16°23’N), Sine Saloum; MNHN 2008.0080 (previously IRD S-443), MNHN 2008.0081 (previously IRD S- 2302), MNHN 2008.0082 (previously IRD S-2306): Keur Bakar Mané ( 13°37’N, 16°17’W), Sine Saloum; MNHN 2008.0083 (previously IRD S-762), MNHN 2008.0084 (previously IRD S-5283): Keur Seny Gueye ( 13°36’N, 16°19’W), Sine Saloum; MNHN 2008.0085 (previously IRD S-855), MNHN 2008.0086 (previously IRD S-858), MNHN 2008.0087 (previously IRD S-1640): Keur Gadji ( 13°38’N, 16°19’W), Sine Saloum; MNHN 2008.0088 (previously IRD S-1283): Keur Santhiou ( 13°39’N, 16°21’W), Sine Saloum; IRSNB 2654 (previously IRD S-605), IRSNB 2655 (previously IRD S-1429), IRSNB 2656 (previously IRD S-1435), IRD S-1439, IRD S-1440, IRD S-1442, IRD S-1461, IRD S-3429, IRD S-3430, IRD S-5692: Dielmo ( 13°43’N, 16°25’N), Sine Saloum; IRD S-2113: Landieni ( 12°33’N, 12°22’W), eastern Senegal; IRD S-5344: Saroudia ( 12°32’N, 11°35’W), eastern Senegal; IRD S-5427: Sambarabougou ( 13°06’N, 11°51’W), eastern Senegal; IRD S-5849, IRD S-5854: Guénoto ( 13°33’N, 13°50’W), eastern Senegal; IRD S-6204: Keur Lamine Diamé ( 13°37’N, 16°16’W), Sine Saloum; IRD S-6461: Touba Baria ( 13°38’N, 16°14’W), Sine Saloum.

Other specimens examined. 86 specimens: Senegal ( 46 specimens): IRD S-343, IRD S-3431: Senegal; IRD S-462: Keur Ayip Kâ ( 13°39’N, 16°19’W), Sine Saloum; IRD S-604, IRD S-606, IRD S-664: Keur Bakar Mané ( 13°37’N, 16°17’W), Sine Saloum; IRD S-856, IRD S-1634: Keur Gadji ( 13°38’N, 16°19’W), Sine Saloum; IRD S-1279, S-1280, S-1281, S-1292, S-1293: Keur Santhiou ( 13°39’N, 16°21’W), Sine Saloum; S-1411, S-1472, S-1482: Dielmo ( 13°43’N, 16°25’W), Sine Saloum; IRD S-1588: Keur Lahim Fatim ( 13°44’N, 16°23’N), Sine Saloum; IRD S-3849: Badiara ( 13°13’N, 14°12’W), Haute Casamance; IRD S-3952: Goundaga ( 12°51’N, 14°05’W), Haute Casamance; IRD S-4806: Tialé ( 15°14’N, 16°49’W), Cayor; IRD S-5085: Oubadji ( 12°40’N, 13°03’W), Sénégal oriental; IRD S-5307: Saroudia ( 12°32’N, 11°35’W), Sénégal oriental; IRD S-5795, IRD S-6090: Keur Momat Souna ( 13°38’N, 16°17’W), Sine Saloum; IRD S- 5851, IRD S-5853: Guénoto ( 13°33’N, 13°50’W), eastern Senegal; IRD S-5862: Médina Djikoye ( 13°37’N, 16°18’W), Sine Saloum; IRD S-6239: Touba Baria ( 13°38’N, 16°14’W), Sine Saloum; IRD S-6656: Takoudialla ( 12°50’N, 14°04’N), Haute Casamance; IRD S-6680: Ségoto ( 13°18’N, 11°49’W), Sénégal oriental; IRD S-7200: Touba Ndiaye ( 15°09’N, 16°52’W), Cayor; IFAN 55-4-13: Cambérène ( 14°45'N, 17°25'W); IFAN 52-11-90, IFAN 53-11-143: Dakar ( 14°42'N, 17°27'W); IFAN 47-1-10, IFAN 47-1-15, IFAN 50-9-149, IFAN 51-12-53, IFAN 52-3-23, IFAN 52-7-47, IFAN 56-5-50: Hann ( 14°43'N, 17°26'W), IFAN 82- 1-2: Keur Massar ( 14°47'N, 17°18'W); IFAN 52-1-8: Malika ( 14°47'N, 17°20'W); IFAN 53-3-20: Ouakam ( 14°43'N, 17°29'W); IFAN 44-1-3: Popenguine ( 14°33'N, 17°07'W). Mali ( 32 specimens): IRD 2353-M, IRD 2354-M: Ballabougou ( 12°52’N, 06°52’W); IRD 238-M: Bangaya ( 13°14’N, 10°43’W); IRD 1179-M, IRD 1181-M: Djinagué ( 12°59’N, 09°52’W); IRD 103-M: Doussoudiana ( 11°09’N, 07°48’W); IRD 2368-M: Koundian ( 13°10’N, 10°40’W); IRD 805-M: Laminina ( 11°12’N, 07°47’W); IRD 1977-M, 2003-M, 2017-M: Mamoroubougou ( 11°13’N, 05°28’W); IRD 1796-M, IRD 3419-M: Npiébougou ( 11°59’N, 08°00’W); IRD 2352-M: Sadjouroubougou ( 12°35’N, 07°44’W); IRD 1591-M: Sare-Soma ( 14°45’N, 03°55’W); IRD 878-M, 957-M: Sebekourani ( 12°12’N, 08°42’W); IRD 184-M, IRD 2102-M, IRD 2109-M, IRD 2118-M, IRD 2145- M, IRD 2186-M, IRD 3606-M, IRD 3617-M, IRD 3618-M, IRD 3683-M: Titiéna ( 11°27’N, 06°33’W); IRD 156-M, IRD 581-M, IRD 2349-M, IRD 2350-M, IRD 2351-M ( 13°09’N, 07°57’W). Niger ( 2 specimens): IRD 201-N: Karosofua ( 13°37’N, 06°37’E); IRD 1504-N: Téla ( 12°08’N, 03°28’E). Burkina Faso ( 2 specimen): LC 6531: Kondio ( 11°37’N, 02°01’E); IFAN 48-2-9: Dano près Diébougou ( 11°09'N, 03°04'W); USNM 237088 8km S of Dana (NW 1202C1). Bénin ( 1 spécimen): LC 7109: Niénié ( 11°22’N, 02°12’E). Guinée ( 1 specimen): IFAN 52-6-34: Niandan-Banie (approximatively 10°20'N, 09°50'W). Nigeria ( 1 specimen): CM 92607 Shagunu, west bank of Kainji Lake ( 10º20’N, 04º28’E).

Diagnosis. Naja senegalensis resembles all other members of the N. haje complex and differs from all other Naja in having a row of subocular scales separating the orbit from the supralabial scales. Naja senegalensis can be distinguished from other species of the N. haje complex through a combination of scale counts and the coloration of juveniles and adults. Comparative scale counts are given in Table 3. Naja senegalensis is distinguishable from N. haje through its higher neck scale row count: N. senegalensis normally has 25 dorsal scale rows around the neck, although some specimens have 23 or 27. By contrast, W. African N. haje have fewer neck scale rows ( 19–21 in five specimens from Niger, 21–23 in three specimens from Nigeria, 21 in one specimen from Tombouctou, Mali). In other parts of Africa, the majority of specimens also have 21 or fewer scale rows around the neck ( Table 3). A cobra specimen from Djibouti, with 27 scale rows around the neck and 23 at midbody, tentatively assigned to the N. haje complex by Ineich (2001), appears to be a spitting cobra. Other scalation characters do not distinguish N. senegalensis from N. haje , although the new species tends to occupy the upper end of the spectrum of ventral scale counts in the complex ( Table 3).

Another diagnostic feature of N. senegalensis is the juvenile pattern: the great majority of juveniles and subadult specimens have a highly contrasting white blotch on the neck, within the dark collar encircling the neck ( Fig. 7 View FIGURE 7 ). This pale patch is present in 37 out of 39 small and medium-sized specimens, but barely discernible or absent in almost all larger adults. However, one of us (LC) recently photographed a large captive adult (approximately 200 cm total length) from the area of Bamako, Mali, that retained a very conspicuous, heart-shaped nuchal mark ( Fig. 8 View FIGURE 8 ). We have never observed this patch in N. haje , and therefore consider its presence to be a diagnostic character for N. senegalensis .

Naja senegalensis differs strongly in coloration from sympatric or parapatric West African N. haje : adults of N. senegalensis are almost invariably uniformly dark brown dorsally, whereas juveniles are greyish dorsally and yellowish ventrally, with a dark collar ( Fig. 7 View FIGURE 7 ) around the neck and usually a white neck blotch. Small adult specimens tend to be dark brown with paler speckles and their ventral side is yellowish. Small adult N. senegalensis from W National Park, in the Niger – Burkina Faso – Benin border region, have a brown dorsal coloration with small reddish dots of one scale each. The entire head, and in particular the supralabial region, are normally uniformly dark brown. In Niger and Nigeria, where both N. senegalensis and N. haje are found (the former in the Sudan savanna, the latter in the Sahelian zone, but with possible areas of sympatry), both adults and juveniles of N. haje display quite different colours: the body of adults is yellow to dark brown dorsally (often mostly yellow, especially in Niger), often with scattered individual dark scales, but the venter is at least partly cream-coloured, or with contrasting light and dark bands or blotches. The sides of the head, and in particular the supralabial region, normally display contrasting areas of pale and dark pigmentation, and, most noticeably, a dark spot under the eye, reminiscent of the “teardrop” marking present in N. nubiae ( Wüster & Broadley, 2003) , and a more or less distinct dark greyish neck band, approximately ten scales wide. Juveniles lack the pale neck patch present in young N. senegalensis . An adult N. haje from Niger is illustrated in Trape & Mané (2006, p. 195).

Elsewhere in Africa, N. haje shows great variation in colour pattern, but differs consistently from that shown in N. senegalensis as follows:

- The Moroccan/Western Saharan population extends into the northern parts of Western Sahara, and specimens have been illustrated by Bons & Geniez (1996, p. 251), Geniez et al. (2004, p. 169, 171) and Dobiey & Vogel (2007, p. 67). Adults are usually uniform black except for a yellowish gular area. Some may be dark brown above and grey below.

- N. haje extends across northern Algeria south of the Atlas Mountains ( Schleich et al., 1996), but no voucher specimens have been examined. LC did not encounter the species during two years that he spent in the region; local people knew it, but reported that it was very rare. Renker (1966) reported encountering a uniformly “sandy brown” specimen at Ghardaia and both black and brown specimens at Bir Ghellalia, Msila Province

- Nine Tunisian specimens showed great variation, but most are yellowish or mottled brown, with head and neck blackish, the venter may be dark mesially or suffused with brown. MNHN 8797 from south Tunisia is red-brown above and purple below. Only a 446 mm male from Sfax (FMNH 83646) has a distinct throat band covering ventrals 8–18. Specimens from Libya are similar (see photo in Schleich et al., 1996, plate 49) but a 1370 mm male from Kouf National Park (FMNH 214914) is brown with yellow flecks above and shows faint banding, while a 610 mm male from near Misurata (FMNH 83058) has black throat bands covering V 3– 6 and 11–25. Kramer & Schnurrenberger (1963) reported that Libyan juveniles are cream with dark dorsal crossbands, black head and neck and a broad black throat band.

- Egyptian specimens are yellow to brown above, often mottled, and the head often darker, with faint darker edges on the head scales and an indication of a “teardrop” marking. FMNH 171897 from Hahîg, Matruh, has 3 yellow bands on the posterior body and 3 on the tail (3 + 3), and FMNH 75232 from northwest of Cairo has 4 + 2 similar bands. Most Egyptian cobras have a single dark throat band covering ventrals ca. 15–25. See photos in Saleh (1997, p. 175), Baha El Din (2006, fig. 109) and Dobiey & Vogel (2007, p. 66).

- No material has been examined from northern Sudan, but most specimens from the south resemble those from Egypt. However, FMNH 190325, a female from Kassala, has a dark brown dorsum with pale streaks and 9 + 2 yellow bands on body and tail, these extend ventrally. FMNH 58468, a 412 mm female from Torit, has two black neck bands on V 12–13 and 15–29, while NMK 3231, a 1880 mm male from Sennar, has brown bands on V 1–9 and 13–27.

- Ethiopian specimens are usually brown with numerous scattered patches of yellow scales, sometimes with a divided yellow band on the neck, but AAU H.664, a male from north of Gondar, has yellow blotches coalescing to form bands caudad, while the venter is blackish with 9 + 2 distinct yellow bands. Dobiey & Vogel (2007, p. 65) illustrate a specimen from Keren, NW Eritrea, which displays a striking pattern of dark brown or black marbling on a creamy-white background. It is unclear whether this is an individual aberrance or a characteristic of the local population.

- Ugandan specimens are yellow to grey-brown, the head and neck often darker and frequently with a faint yellow band on the neck. MUZM (un-numbered), a 900 mm female from Soroti, is black above with 7 + 2 yellow bands, and two juveniles (NMZB-UM 5236–7) from this area show faint banding on the dorsum. A black throat band usually covers ca. v 12–24.

- Kenyan specimens are usually mottled brown and yellow above, with contrasting facial and supralabial markings, sometimes with a yellow band on the neck, rarely other bands caudad. Usually a dark throat band covers ca. V 16–25, rest of venter yellow with brown blotches. Tanzanian specimens are similar, but KMH 3184, a 1063mm female from Mangola, is grey-brown above, with one yellow band on the nape, three on the posterior body and two on the tail.

- There are few records of N. haje from the north-eastern Democratic Republic of Congo ( DRC) and northern Central African Republic ( CAR). One of us (LC) collected four specimens in northern CAR, which do not differ from those of northern Cameroon, where all the specimens collected by one of us (LC) are very dark, grey or black but not brown, with a pale throat, and superficially similar to Moroccan specimens (photograph in Chirio & LeBreton, 2007, p. 579).

Naja senegalensis differs from N. anchietae , N. annulifera and N. arabica in having consistently higher scale row numbers around the neck (23 or more vs. 21 or fewer in the three other species). Additionally, N. anchietae and N. annulifera differ in having a pointed, enlarged rostral scale, fewer ventral scales (males: maximum 201; females: maximum 206, vs. minimally 205 and 219, respectively, in N. senegalensis ) and, with few exceptions, 19 or fewer midbody dorsal scale rows.

Naja arabica also differs from N. senegalensis in colour pattern, which is highly variable ( Gasperetti, 1988; Egan, 2007). Specimens from south-west Saudi Arabia and Yemen may be blackish-brown above and below, or with the head and neck black, the rest of the body yellow, the venter often dark mesially. Gasperetti (1988) noted that some individuals were dull black, copper coloured, or various shades of brown or yellow, with blackish top of head and tail, and Egan (2007) additionally noted entirely orange specimens with yellow heads. An adult female from Dhofar, Oman (BMNH 1976.1487) is yellow-brown, but with a black head and neck and becoming black caudad and with a black venter. A 418mm male from the same region (BMNH 1977.1198) has a brown head, yellow-brown dorsum and yellow venter, and van der Kooij (2001, p. 59) illustrates a largely black specimen with coppery lower sides and described a “copper coloured ventral surface”, although this is not evident in the photo.

Description of holotype ( Fig. 4–6 View FIGURE 4 View FIGURE 5 View FIGURE 6 ). The holotype (MNHN 2008.0074, previously IRD S-8549) is an adult male of the following dimensions: total length 1430 mm, snout-vent length 1175 mm, tail length 255 mm, ratio total length: tail length 5.3.

Head broad and short, weakly distinct from the neck, which is partly dilated. Snout rounded. Eye small, pupil round. Rostral as broad as high, clearly visible from above. The nostril is large and entirely divides the nasal. Two internasals, two prefrontals. The frontal is slightly longer than the prefrontals and internasals, their greatest width is similar. Loreal absent. A single rectangular preocular, twice as long as wide, between eye and nasal. Two postoculars on the left, three on the right. Two suboculars on the left and three on the right entirely separate the eye from the supralabials. 1+ 2 temporals on right, 1+3 on left. Seven supralabials, sixth is largest. Eight infralabials, the first four contact the anterior chin shields. No cuneates. The posterior chin shields are as long as but narrower than the anterior ones. Dorsal scales smooth and oblique, in 25 rows around the neck, 21 around midbody and 15 ahead of the vent. Vertebral row not enlarged. 211 ventrals, anal single. 65 subcaudals, all divided except the second to the ninth, which are single. Stomach content: one Bufo xeros .

Upper side of head, body and tail entirely grey-brown. Lower flanks lighter on first two dorsal scale rows, except at anterior and posterior end of body, where they are of the same colour as the dorsum. Lower side of head is grey-brown, similar to the upper side. Underside includes a dark grey area extending from the fifth to the 30th ventral scale, excluding the 12th and 17th ventrals, which are partially light. From the 31st ventral, the dominant colour of the ventrals is yellowish, with dark spots that become fainter towards the posterior part of the body. Subcaudals entirely yellowish, except on the terminal third of the tail, where they become progressively darker.

Description of paratypes. The 31 paratypes include 17 males and 14 females. The largest male (IRD S- 3429) measured 2065 mm, the largest female (IRD S-1640) 2315 mm in total length. Mean length of males was 1035 mm (SD = 699 mm), of females 1110 mm (SD = 654 mm). The total length: tail length ratio ranged from 5.7 to 6.6 in males (mean: 6.2; SD: 0.2) and from 6.1 to 6.8 in females (mean 6.4, SD 0.3). Midbody dorsal scale rows 21 in males and 21 ( N = 13) or 23 ( N = 1) in females. The number of scale rows around the neck is 23 ( 3 males, 1 female), 24 ( 1 female), 25 ( 13 males and 9 females), 26 ( 1 female) or 27 ( 2 males, 2 females). Ventrals 205–216 (mean 211.7, SD 2.7) in males, 219–225 (mean 222.3, SD 1.6) in females. Subcaudals 59–65 in males (mean 61.5, SD 1.5) and 56–64 in females (mean 59.9, SD 2.2), all or mostly divided. Nasal always fully divided, loreal always absent. Preocular always single, elongate and rectangular. 1–3 postoculars, 1–3 suboculars, the total number of scales around the eye varying from 5 to 7. Supralabials always 7, except in one specimen with 8 on one side. Temporals 1+2 ( N = 5), 1+3 ( N =18), or a combination of the above ( N = 9). Nuchals 7 ( N = 19), 8 ( N =9) or 9 ( N = 3). Cuneates number 0 ( N = 6), 1 ( N = 20), or 1 on one side only ( N = 5). When present, cuneate always between 4th and 5th infralabials. The examination of stomach contents revealed Bufo xeros and Rhamphiophis oxyrhynchus in two specimens.

Juveniles ( 17 specimens measuring under 1000 mm in total length) are pale greyish to greyish-brown dorsally, except the top of the head, the neck and the anterior body, which are dark grey or blackish. On all but one of the juveniles, a white blotch was present on the neck, contrasting strongly with the dark or black colour of the rest of the forebody ( Fig. 7 View FIGURE 7 ). The venter is largely pale beige or yellowish, except for a band of approximately 20 ventrals, usually situated between the 5th and the 30th ventral, which is entirely black. In adults, the dorsal coloration is dark brown or greyish brown, the top of the head and the forebody often being slightly darker, this representing a remnant of the juvenile coloration. A paler neck blotch is sometimes visible. The venter is slightly paler than the dorsum (larger specimens) or yellowish (medium-sized specimens), with the exception of approximately 20 scales under the anterior body, which are dark brown or dark grey. Underside of head usually dark in large specimens.

Description of other specimens. The other specimens examined present the same general characteristics as the type series, both in terms of scalation and juvenile and adult coloration. The largest specimen is a female from Mali, measuring 2450 mm (IRD 805-M). The largest male measures 2205 mm (IRD S-343, Senegal). The eye is consistently separated from the supralabials by one or several suboculars. The midbody scale rows number 21, rarely 23, and ventral and subcaudal counts agree with the type series. In males from Mali, ventrals number 211–216, and subcaudals 60–64, and in females, the corresponding counts are 222–225 and 56–64. The number of dorsal scale rows around the neck ranges from 25 ( N =22) to 27 ( N = 2) in the 24 specimens from Mali and Niger in which this character has been recorded.

Etymology. The name of the new species refers to the country of origin of the type series.

Distribution and ecology. Naja senegalensis is widely distributed in the savannas of western Africa from Senegal east to south-western Niger, Benin and western Nigeria ( Fig. 9 View FIGURE 9 ). In Senegal, it appears to be found throughout most of the country, although records are lacking from the arid northeast. It is widespread in southern Mali, and has also been recorded from north-western Guinea, Burkina Faso, south-western Niger and northern Benin ( Roman, 1973, 1980; Trape & Mané, 2006). The eastern limits of its range are poorly documented. The material from Burkina Faso reported by Roman consisted entirely of N. senegalensis , with the apparent exception of a single specimen from Dori in the extreme northeast of the country (LC, observation). A single specimen is known from Shagunu, on the shores of Kainji Reservoir, western Nigeria (CM 92607), whereas a number of specimens of the N. haje complex imported from Nigeria by the Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine are referable to N. haje , as is material from northern Cameroon and the Central African Republic ( Chirio & Ineich, 2006) examined by one of us (LC). The distribution of N. haje extends to the north and east of that of N. senegalensis at least as far as Tombouctou, Mali (NMZB 13981).

Naja senegalensis occupies a variety of savanna habitats. In northern Benin and eastern Burkina Faso, it seems to show a predilection for riparian situations: in the villages around W National Park, villagers know it well and state that it always lives near water. One of us (LC) found some burrows with shed skins near small temporary streams, and the preserved specimens were found in the same biotopes (one was even caught in a fisherman’s net). This species seems to be excluded from the banks of larger, permanent rivers by N. melanoleuca in W National Park, western Niger. On the other hand, in western Senegal (Sine-Saloum), author JFT has not observed any tendency for the species to be associated with water bodies.

Biogeography. The historical biogeography of the Naja haje complex is of considerable interest because of its widespread and fragmented distribution. Wüster et al. (2007) used molecular dating to infer the historical biogeography of the cobras. The divergence between the Naja haje group and N. nivea was estimated at approximately 12 Mya, and that between N. annulifera and N. haje at approx. 7 Mya, albeit with wide confidence intervals. This estimated time of origin for the N. haje complex corresponds closely to the late Miocene expansion of C4 grasslands ( Cerling et al., 2006), which may have favoured the spread of this clade of open-habitat cobras.

Naja senegalensis joins the list of long-isolated species that appear to be endemic to the Sudano-Sahelian savannas of West Africa, exemplified also by snake species such as Naja katiensis (Wüster et al., 2007) , Atractaspis dahomeyensis and A. micropholis ( Trape & Mané, 2006) , Hemorrhois dorri ( Trape & Mané, 2006) , and lizards such as the gekkonid Hemitheconyx caudicinctus and the agamid Agama sankarica . Some other species, such as Psammophis praeornatus ( Trape & Mané, 2006; Kelly et al., 2008) and Echis ocellatus (Pook et al., in press) also have primarily West African savanna distributions, although their ranges extend further east to the Central African Republic. The reasons for the apparent isolation of multiple co-distributed West African savanna forms remain unclear, because, irrespective of Plio-Pleistocene fragmentation and expansion of the equatorial forests of Africa, a savanna connection would almost certainly have persisted between the Sudan and Sahel savannas of West Africa and the open formations of East Africa. Additional molecular dating studies would be needed to ascertain whether these co-distributed West African savanna isolates result from a common event, or whether these distributions were established at different times.

The origin of the Arabian Peninsula populations of the complex appears to be a rather more recent event, most likely dating back to the late Pliocene/early Pleistocene, long after the initial opening of the Red Sea in the late Oligocene/early Miocene, or later Miocene land connections across the southern Red Sea ( Bosworth et al., 2005; Fernandes et al., 2006). Past phylogeographic studies have proposed a variety of different ages for trans-Red Sea relationships. Amer & Kumazawa (2005) estimated an age of 11–15 My for the divergence between Arabian and African clades of Uromastyx, Pook et al. (in press) estimated the split between African and Arabian clades of the E. pyramidum complex at 8 Mya, whereas Winney et al. (2004) estimated a mid– late Pleistocene crossing of the Red Sea to explain the presence of the hamadryas View in CoL baboon ( Papio hamadryas View in CoL ) in Arabia. The origin of Naja arabica appears to lie between these extremes, and was dated at approximately 1.75 Mya by Pook et al. (in press). The reciprocal monophyly of N. arabica and all African N. haje does not allow the route of colonization from Africa to Arabia to be inferred: N. haje occurs both in Egypt and in the Horn of Africa, so that dispersal either across the Sinai Peninsula into north-western Arabia or across the Bab- El-Mandab into southern Arabia remain tenable hypotheses. Additional mtDNA data from populations from the Horn of Africa might shed further light on the question of the origin of the Arabian populations of this complex ( Ineich, 2001).

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.

|

Kingdom |

|

|

Phylum |

|

|

Class |

|

|

Order |

|

|

Family |

|

|

Genus |

Naja senegalensis

| Trape, Jean-François, Chirio, Laurent, Broadley, Donald G. & Wüster, Wolfgang 2009 |

Naja katiensis (Wüster et al. , 2007)

| Wuster et al. 2007 |

A. micropholis ( Trape & Mané, 2006 )

| Trape & Mane 2006 |

Hemorrhois dorri ( Trape & Mané, 2006 )

| Trape & Mane 2006 |

N. nubiae ( Wüster & Broadley, 2003 )

| Wuster & Broadley 2003 |