Parantechinus apicalis (Gray, 1842)

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6608102 |

|

DOI |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6602737 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/EA7087C1-FFAC-2441-FF09-FBA309F20BCC |

|

treatment provided by |

Felipe |

|

scientific name |

Parantechinus apicalis |

| status |

|

5. View On

Dibbler

Parantechinus apicalis View in CoL

French: Dibbler / German: Sprenkelbeutelmaus / Spanish: Dibbler

Other common names: Southern Dibbler

Taxonomy. Phascogale apicalis Gray, 1842 ,

south-west Western Australia, Australia.

In 1947, G. H. H. Tate erected Parantechinus (his P. apicalis ) to accommodate one of three species that had originally been classified as Phascogale . On the basis of their reduced or absent fourth premolar teeth in both mandibles (P4), and their inflated auditory bullae (bulbous ear chamber bone), Tate placed this genus in his subfamily Dasyurinae along with Dasyurus , Sarcophilus , Pseudantechinus , and Myoictis . In 1964, W. D. L. Ride rejected the significance of P4 size variation and allocated Parantechinus to Antechinus . Then in 1982, phylogenetic analyses of allozyme data confirmed Tate’s original contention that P. apicalis was more closely related to Dasyurus than to Antechinus . That same year, M. Archer duly resurrected Parantechinus . A recent phylogenetic study using mtDNA and nDNA found that P. apicalis , while genetically distinct, was not consistently resolved as sister to either the New Guinean Myoictis or the Kaluta ( Dasykaluta rosamondae ). Indeed, a sister group relationship of P. apicalis and the Sandstone Pseudantechinus ( Pseudantechinus bilarni ) could not be rejected. Monotypic.

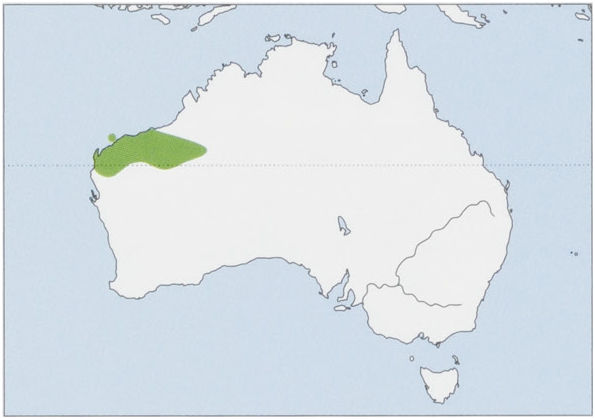

Distribution. SW Australia, only known from Fitzgerald River National Park in Western Australia and on Boullanger and Whitlock Is. Successfully translocated into Peniup proposed nature reserve, Stirling Range National Park, and Escape I, all in Western Australia. View Figure

Descriptive notes. Head-body 14-5 cm (males) and 14 cm (females), tail 10-5—-11:5 cm (males) and 9-5 cm (females); weight 60-125 g (males) and 40-73 g (females). The Dibbleris sexually dimorphic in size. Individuals on Boullanger and Whitlock islands are significantly smaller than those on the mainland. The Dibbler is brownish-gray flecked, with white above and grayish-white tinged with yellow below. Dibblers are readily distinguished by their tapering, hairy tail, white rings around eyes, and flecked appearance of their coarse fur.

Habitat. Scrub and heath plant communities. Time since burn in an area is apparently important for persistence of Dibblers, with older flora being preferred. Possibly, Dibblers will occupy younger vegetation when Red Fox (Vulpes vulpes) are excluded. One study conducted on Boullanger and Whitlock islands found that Dibblers preferred dense vegetation. This was particularly the case on Whitlock Island, where trapping success rate was greatest in thick, low, closed heath and succulent heath dominated by Atriplex cinerea (Chenopodiaceae) and Nitraria billardierei ( Zygophyllaceae ) found in the center and southern end of the island. On Boullanger Island, Dibblers also preferred dense vegetation because more individuals were caught in low, closed heath and fore-dune heath dominated by Scaevola crassifolia (Goodeniaceae) , Olearia axillaris ( Asteraceae ), and Myoporum insulare (Myoporaceae) than in open scrubland and thicket of Lepidosperma gladiatum (Cyperaceae) . In this area, open scrubland had large, recently introduced Acacia (Fabaceae) trees; during this study, researchers observed an increase in percent cover of this vegetation. This corresponded to a decrease in numbers of Dibblers trapped in low closed heath and fore-dune heath habitats and comparatively more Dibblers captured in open scrub.

Food and Feeding. The Dibbler eats a variety of arthropods and some small vertebrates. On Boullanger and Whitlock islands, their diets are ¢.20% plant material; fecal analysis indicated that they took prey from ten orders of invertebrates, including spiders, cockroaches, beetles, earwigs, bugs, flies, wasps, scorpions, grasshoppers, and crickets. Prey was up to 2-5 cm in length. In one study, Dibblers fed opportunistically on whatever was available; thus, they were deemed insectivorous generalists. Another study found that on Whitlock Island,significantly greater trapping success was recorded in dune scrubland dominated by N. billardierei and fore-dune heath than in succulent heath. Feces contained arthropods (65%) and vegetable matter (25%), confirming that Dibblers on islands were chiefly insectivorous and only rarely eat vertebrate prey.

Breeding. Dibblers breed annually in March, and females carry as many as eight young in their shallow pouch. Young remain dependent on the mother for 3-4 months; they are ready to breed at 10-11 months old. During mating, a single copulation may last for several hours; a mating pair may copulate more than once during the mating period. Captive individuals (male and female) from mainland and island populations may enter breeding condition in at least two successive seasons. In the wild, in some years only, all males on Boullanger Island die after theirfirst breeding season. Thisis in contrast to mainland males that survive beyond their first breeding season in the field and laboratory. In a study of reproduction in captive Dibblers from islands, females were monoestrous; island males were potentially capable of breeding in more than one season. Dibblers from islands were smaller than mainland conspecifics, but the estimated length of pseudo-pregnancy was similar. This research suggested that die-off of males observed in each of the three years following their discovery was not an inevitable event; rather, it was a facultative response to adverse environmental factors and quite different from physiological, stress-related response seen in species of Antechinus , Phascogale , and Dasykaluta .

Activity patterns. There is no information available for this species.

Movements, Home range and Social organization. There is no information available for this species.

Status and Conservation. Classified as Endangered on The IUCN Red List. Listed as Endangered in Australia. The Dibbler was presumed extinct until a pair was collected by chance in 1967 at Cheyne Beach near Albany, on the southern coast of Western Australia. Small numbers of individuals were later captured at several localities on the mainland from Fitzgerald River National Park to the east of Cheyne Beach and from Torndirrup National Park in the west. In early days of European settlement of Western Australia, the Dibbler was far more widespread, being recorded from the Moore River region to King George Sound. Clearing of land for farming from the mid-1800s onward may have been responsible for reducing its distribution. Nevertheless, geologically recent fossil remains have been found from Shark Bay to Bremer Bay in Western Australia and from Eyre Peninsula in South Australia, indicating that the Dibbler’s distribution was contracting even prior to European arrival. The Dibbler is a rare species; the global population probably consists of ¢.500-1000 mature individuals, and there have been some population declines. It occurs in less than 5000 km?its distribution is severely fragmented, and there is continuing decline in the extent and quality ofits habitat. Existence of apparently thriving island populations suggests that isolation has afforded some protection to the Dibbler. The three island populations, not discovered until 1985, include ¢.200 individuals and the translocated population on Escape Island (from captive-bred individuals from Boullanger and Whitlock islands) consists of ¢.30 adults. Island populations have declined in recent decades. Population size of Dibblers fluctuatessignificantly with rainfall. Introduced Red Fox and domestic and feralcats are known to prey on Dibblers and are found throughoutits known mainland distribution; however, these pests fortunately are not present on the islands. The plant disease Phytophthora cinnamomi (a soil-borne water mold that causes dieback) is a threat to Dibblers because it adversely alters their habitat. Introduced House Mice ( Mus musculus ) are also a competitive threat on Boullanger and Whitlock islands. The Dibbler is dependent on habitat that has not been recently burned; thus, frequent and intense fire is a major threat. A recovery plan was developed for the species for 2003-2013. Captive breeding of individuals from Fitzgerald River permitted translocation of Dibblers to the proposed Peniup Nature Reserve and Stirling Range National Park. Recommendations made in the Dibbler recovery plan include monitoring known populations; surveying for additional populations; protecting existing populations from threatening processes (including prevention of exotic predators from the islands); controlling red fox and cats on mainland sites with Dibblers; implementing fire management; preventing spread of dieback; studying feasibility of eradicating mice from Boullanger and Whitlock islands; maintaining and expanding captive breeding populations for further translocations; and promoting awareness of Dibbler conservation to the public and land managers.

Bibliography. Archer (1982c), Baverstock et al. (1982), Bencini et al. (2001), Dickman & Braithwaite (1992), Friend (2004), Friend, Burbidge & Morris (2008), Miller et al. (2003), Mills & Bencini (2000), Mills et al. (2004), Moro (2003), Ride (1964), Tate (1947), Westerman et al. (2007), Woolley (1971b, 1977, 1980, 1991c, 2008d), Woolley & Valente (1982).

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.

|

Kingdom |

|

|

Phylum |

|

|

Class |

|

|

SubClass |

Metatheria |

|

Order |

|

|

Family |

|

|

Genus |

Parantechinus apicalis

| Russell A. Mittermeier & Don E. Wilson 2015 |

Phascogale apicalis

| Gray 1842 |