Brabocetus gigaseorum, Colpaert, Bosselaers & Lambert, 2015

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/ 10.4202/app.00115.2014 |

|

publication LSID |

lsid:zoobank.org:pub:79DEA951-9785-4515-BA52-5684BA822F37 |

|

DOI |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.10989429 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/3A577BF5-B6A6-4F9C-8524-2F40912A8F11 |

|

taxon LSID |

lsid:zoobank.org:act:3A577BF5-B6A6-4F9C-8524-2F40912A8F11 |

|

treatment provided by |

Felipe |

|

scientific name |

Brabocetus gigaseorum |

| status |

sp. nov. |

Brabocetus gigaseorum sp. nov.

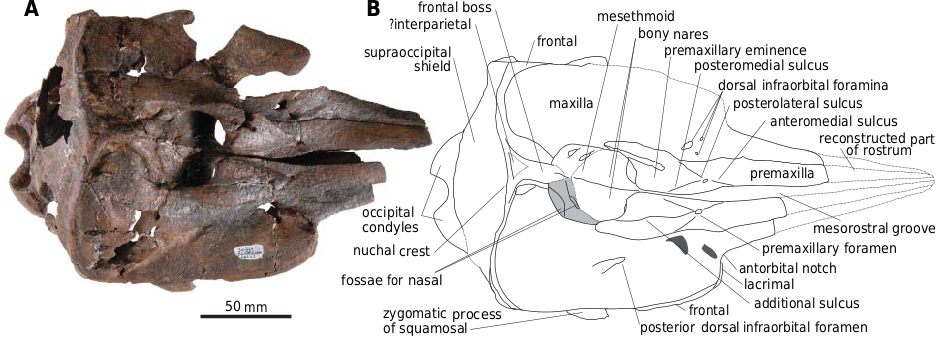

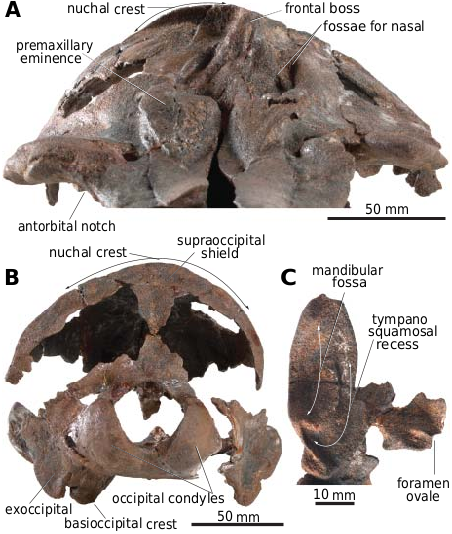

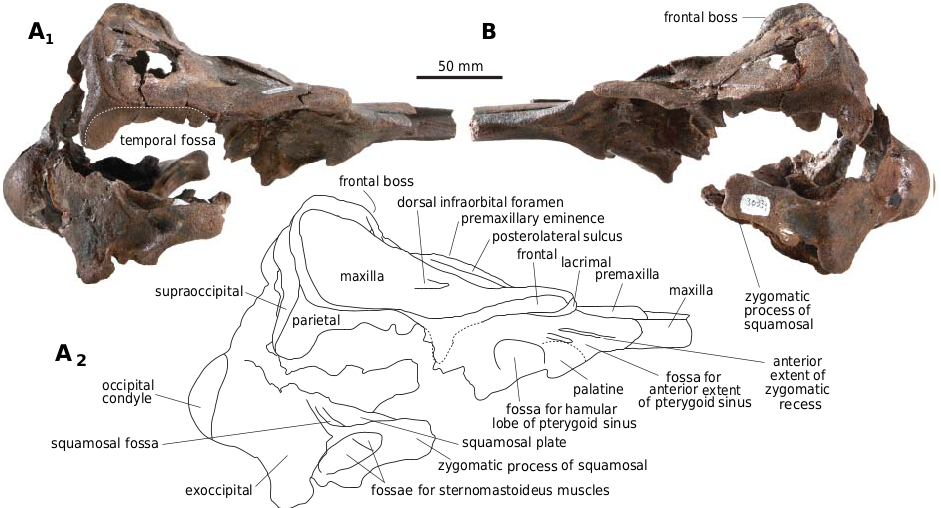

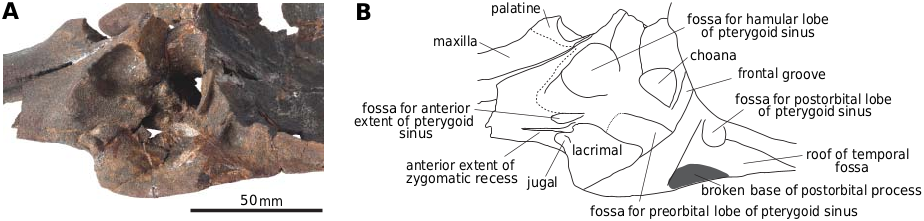

Figs. 2 View Fig , 3 View Fig , 5–7 View Fig View Fig View Fig .

Etymology: Honouring Paul and Pierre Gigase (father and son) for their long-term effort in collecting fossil marine mammal remains in the area of Antwerp and for generously donating the specimen IRSNB M. 2171 to the IRSNB.

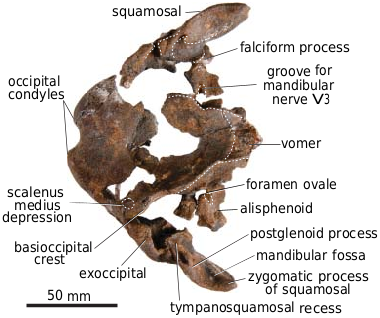

Holotype: IRSNB M. 2171, a partial skull in three fragments, lacking the anterior part of the rostrum, part of the left supraorbital process, the nasals, the pterygoids, and some elements of the cerebral cavity and basicranium.

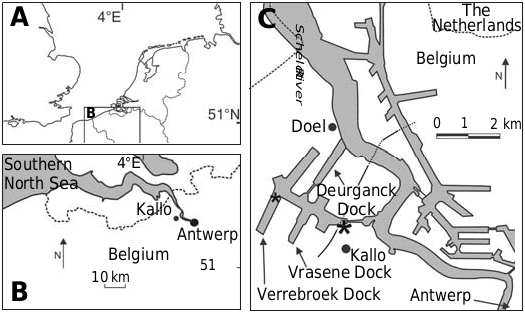

Type locality: Beverentunnel , left bank of the River Scheldt , Antwerp Harbour, northern Belgium ( Fig. 1 View Fig ). The locality is situated two kilometres north of the village of Kallo. Geographic coordinates: N 51°15 ′ 50 ″, E 4°16 ′ 19 ″ GoogleMaps .

Type horizon: The skull was found in the Kattendijk Formation, 2 m below the Oorderen Sands Member, Lillo Formation, in a layer of grey glauconitic sand without mollusc shells. The Kattendijk Formation is dated from the early Pliocene (Zanclean) based on dinoflagellates, foraminifers, and molluscs ( Vandenberghe et al. 1998; Louwye et al. 2004), more precisely between 5 and 4.4 Ma ( De Schepper et al. 2009). This unit represents a neritic deposition (30–50 m water depth) with open-marine influence, under a warm to temperate climate ( De Schepper et al. 2009).

Diagnosis.— Brabocetus gigaseorum sp. nov. has a cranium intermediate in size between that of the extant species Neophocaena phocaenoides and Phocoenoides dalli . It differs from all other phocoenids except Septemtriocetus in having a frontal boss that is longer than wide. It differs from all other phocoenids except Haborophocoena in the anteromedial sulcus being shorter than the posteromedial sulcus. It possibly differs from all extinct phocoenids except Miophocaena in the presence of an additional longitudinal sulcus across the premaxillary eminences. It differs from all phocoenids except Haborophocoena , Miophocaena , Piscolithax tedfordi , and Septemtriocetus , in that the level of the anterior margin of the bony nares is in line with the postorbital process of the frontal; from all other phocoenids except Haborophocoena , Miophocaena , Neophocaena , Piscolithax tedfordi , and Septemtriocetus in that the first anterior dorsal infraorbital foramen is distinctly posterior to the antorbital notch; from Haborophocoena , Miophocaena , Numataphocoena , Piscolithax spp. , Pterophocaena , Semirostrum , and Septemtriocetus in the anterolaterally widely-open antorbital notch, not laterally limited by an extension of the antorbital process; and from extant phocoenids in a more pronounced asymmetry of the vertex, with medial sutures more distinctly shifted to the left side. It further differs from the other North Sea fossil phocoenid Septemtriocetus in that it possesses: an anteriorly longer pterygoid sinus fossa, reaching the level of the antorbital notch; a higher premaxillary eminence, overhanging the posterolateral sulcus; a significantly transversely narrower frontal boss; a lower, not dorsally pointed temporal fossa; a deeper and longer squamosal fossa; and a postglenoid process of the squamosal being thickened in lateral view.

Description

Based on the anteriorly converging and rectilinear lateral margins of the maxillae at the rostrum base, a tentative reconstruction of the outline of the pointed rostrum of Brabocetus gigaseorum is provided ( Fig. 2 View Fig ). This reconstruction suggests a rostrum length shorter than the cranium length, a feature shared with extant phocoenids and possibly Septemtriocetus , but unlike the longer-snouted extinct phocoenids Lomacetus , Piscolithax , and probably Salumiphocaena ( Wilson 1973; Barnes 1984; Muizon 1984, 1988b; Lambert 2008). However, a more complete specimen is needed to confirm this statement. The dimensions of the cranium ( Table 1 View Table 1 ; pre- and postorbital widths, length from the antorbital notch to the nuchal crest) are roughly intermediate between those of the extant species Neophocaena phocaenoides and Phocoenoides dalli , and slightly smaller than in the holotype of Septemtriocetus bosselaersi . The small temporal fossa is still anteroposteriorly longer than the orbit and the roof of the former is slightly higher. The cranium displays a high degree of asymmetry that is especially developed in the region of the bony nares and vertex. This asymmetry is expressed as a shift to the left (ca. 15° in comparison to the sagittal plane of the skull), which is particularly conspicuous in anterior view ( Fig. 3A View Fig ). Differences in width and height of left and right elements are detailed below.

Premaxilla.—In dorsal view, from the preserved anterior end of the rostrum, the premaxilla widens until the level of the antorbital notch, where its width equals the width of the maxilla ( Fig. 2 View Fig ). From that level onwards, the lateral margin of the bone becomes slightly concave over 30–35 mm; it is followed backwards by the convex lateral margin of the premaxillary eminence. The maximum width of the mesorostral groove occurs at the level of the antorbital notches, from where the opening narrows backwards to terminate where the medial margins of the premaxillary eminences nearly abut.

Best preserved on the right side, the tiny elliptical premaxillary foramen (transverse diameter = 2 mm) is located posterior to the level of the antorbital notch. A short and shallow anteromedial sulcus originates from each premaxillary foramen; by contrast the posteromedial sulcus is longer. Consequently, the portion of the prenarial triangle posterior to the premaxillary foramen is longer than the portion anterior to the foramen. A roughly similar condition is seen only in Haborophocoena , whereas other phocoenids, including the extant species, display a longer anteromedial sulcus. Together with the long posterolateral sulcus, the posteromedial sulcus demarcates the anteriorly pointed and moderately elevated premaxillary eminence ( Figs. 2 View Fig , 3A View Fig ). The left eminence is narrower (maximum width 22 mm for 25 mm on the right) and higher (maximum height relative to the lateral maxilla 7.5 mm for 6 mm on the right) than the right eminence. Each eminence is transversely and longitudinally convex, with the lateral margin distinctly overhanging the posterolateral sulcus and part of the maxilla on the left side). The right eminence is crossed by a thin longitudinal groove, tentatively interpreted as the additional sulcus observed in extant phocoenids and Miophocaena ( Murakami et al. 2012b) . An alternative, but less likely interpretation would be that this groove is due to a longitudinal fracture of the eminence following the path of an underlying canal inside the premaxilla. A wider groove is exposed only on the posterior part of the left eminence, the dorsal exposure of which was possibly increased due to surface wear. The posteromedial corner of each eminence is truncated (slightly damaged on the left side), as it is in most extinct phocoenids and the fossil delphinoid Albireo . This feature most likely indicates the presence of maxillary ossicles on the anterior margin of the bony nares, as observed in extant phocoenids ( Barnes 1984; Muizon 1988a). Although wider on the right side of the skull, the portion of the premaxilla along the bony nares is narrow and ends before the posterolateral corner of the naris. A similar condition is observed in all phocoenids, except Archaeophocaena , Haborophocoena minutus , and Miophocaena , which display premaxillae wider and longer towards the vertex ( Ichishima and Kimura 2009; Murakami et al. 2012b).

Maxilla.—Only the right antorbital notch is preserved. In dorsal view, the notch is anterolaterally widely open ( Fig. 2 View Fig ). Consisting of the maxilla and lacrimal, the posterior wall is directed transversely, lacking an anterolateral projection. This major difference with Septemtriocetus is observed in most extant phocoenids, Australithax , Lomacetus , and possibly Salumiphocaena . Although incomplete in this area, the left maxilla bears three dorsal infraorbital foramina posteromedial to the corresponding notch: two small anterior foramina with a diameter not exceeding 2 mm and a larger posterior foramen with a transverse diameter of 6 mm. The anteromedial-most foramen is conjoined with a shallow groove anterolaterally. On the right side, a large opening posteromedial to the antorbital notch is probably due to damage of an area pierced by several dorsal infraorbital foramina. In the orbital region, the dorsal surface of the maxilla is smooth and moderately convex. Its lateral margin is thin. A large posterior dorsal infraorbital foramen is in line transversely with the level of the lost postorbital process of the frontal, and 12 mm lateral to the premaxilla. The left maxilla is exposed dorsally as a narrow strip medial to the corresponding premaxilla on the anterolateral corner of the bony naris, but this exposure may have been accentuated by wear of the overlying premaxilla. The dorsal surface of the maxilla is distinctly convex between the temporal fossa and the vertex. The maxilla reaches the nuchal crest over most of its posterior border, except in its posteromedial corner, where the concave dorsal surface of the frontal is exposed. The maxilla only contacts the frontal boss in the anterior part of the latter.

In lateral view, the medial part of the maxilla ascends gradually towards the vertex, although less abruptly than in Phocoena spp. and Phocoenoides dalli , whereas the bone slopes down posterolaterally from the orbit region to the postorbital process. The posterior end of the alveolar groove is preserved on the left side, beginning 33 mm anterior to the antorbital notch. However, the spongy bone of this area is partially worn and no detail of the alveoli (if originally present) is preserved. The palatal surface of the maxillae between the anterior tips of the palatines is wide and flat, as in other phocoenids and monodontids. On each maxilla, a longitudinal sulcus indicates the presence of a major palatine foramen anterior to the maxilla-palatine suture.

An anteroposteriorly directed thin groove on the lateral side of the maxilla originates medial to the jugal and extends for a short distance (25 mm) on the rostral base ( Fig. 6 View Fig ). According to Mead and Fordyce (2009), this groove may correspond to the anterior extent of the zygomatic recess, the latter housing the maxillary process of the jugal. Ventromedial to this groove, a broader and anteroposteriorly elongated depression is interpreted as a fossa for an anterior extent of the pterygoid sinus, possibly homologous to the anterior sinus fossa present in extant delphinids but presumably not in extant phocoenids ( Fraser and Purves 1960; Mead and Fordyce 2009).

Mesethmoid.—Although the mesethmoid is not visible in dorsal view between the premaxillary eminences, it forms a thin and low nasal septum between the bony nares. Below the frontal boss, the transverse plate-like mesethmoid forms the posterior wall of the bony nares. This plate is proportionally wider and less erect than in extant phocoenids.

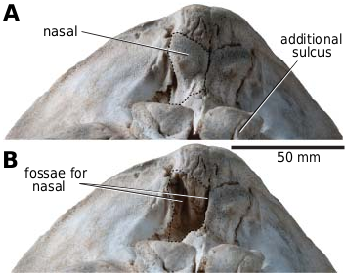

Nasal.—As in the holotype of Septemtriocetus bosselaersi and several other fossil phocoenid specimens, both nasals are lost. Anteroventrolateral to the frontal boss, a shallow fossa is observed above the mesethmoid on each side of the specimen ( Fig. 2 View Fig ). This fossa is crossed by an oblique low ridge descending from the frontal boss ventrolaterally and the deepest portion of each fossa is located dorsolaterally. Similar features on a juvenile skull of Phocoena phocoena , of which one nasal could be removed ( Fig. 4 View Fig ), indicate that these fossae in the frontals held the nasals in life. Consequently, originally each wide nasal extended much more laterally than the frontal boss, with a lateral limit in line with the lateral margin of the bony nares. The mesethmoid formed a dorsomedial projection between the nasals.

Frontal.—Posterior to the fossae for the nasals, the frontal boss is longer than wide ( Fig. 2 View Fig ), as in Septemtriocetus , and transversely narrower than in any other phocoenid, somewhat more similar to the monodontid Delphinapterus . It should be noted that this area is unknown in Pterophocaena and poorly known in Archaeophocaena and Numataphocoena ( Ichishima and Kimura 2000; Murakami et al. 2012b). The right wall of this transversely pinched frontal boss is relatively high, with a dorsal margin forming the top of the skull and slightly overhanging the rest of the wall. This right wall is located far beyond the sagittal plane of the skull on the left side, as is also seen in Haborophocoena and Septemtriocetus . The left wall slopes more gradually towards the corresponding maxilla. Although the interfrontal suture is visible on the anterior surface of the frontal boss, the state of preservation of the posterior part of the boss precludes a detailed description, including the potential presence of an interparietal ( Fig. 2 View Fig ).

In lateral view, the preorbital process of the frontal is barely thickened, roughly continuous with the supraorbital portion ( Fig. 5 View Fig ). Although no postorbital process is preserved, the broken surface at the base of the right process indicates a process in line with the anterior half of the bony nares.

In ventral view of the orbit region, a deep fossa for the postorbital lobe of the pterygoid sinus excavates the frontal medial to the infratemporal crest ( Fig. 6 View Fig ). This fossa is deeper than in the holotype of Septemtriocetus bosselaersi , but its extent is variable in extant phocoenids (OL personal observations). The fossa for the preorbital lobe of the pterygoid sinus extends posterodorsally for a short distance above the frontal groove, close to the configuration of the same in Septemtriocetus . This feature is also present in some extinct phocoenids, as well as some extant delphinids, whereas it is more developed in extant phocoenids ( Fraser and Purves 1960). The roof of the temporal fossa extends for two thirds of the length of the fossa. This roof is proportionally longer anteroposteriorly than in extant phocoenids (most likely linked to the proportionally less transversely inflated cerebral hemispheres), but transversely narrower than in Septemtriocetus . Supraoccipital.—The nuchal crest is only poorly elevated against the frontal boss, unlike that in Piscolithax spp. and several extant phocoenids ( Muizon 1984; Lambert 2008). Lateral to the vertex, the nuchal crest is higher and more acute on the right side ( Fig. 3A, B View Fig ), overhanging the maxilla and frontal.At the top of the right nuchal crest lies the weakly developed external occipital protuberance. A shallow groove extends from the protuberance towards the foramen magnum. The supraoccipital shield slopes more steeply posteroventrally (mean angle of ca. 50° to the horizontal plane over the first 45 mm, taken mediodorsally in lateral view) than in extant phocoenids, due to its less posteriorly developed cerebral hemispheres ( Fig. 5 View Fig ).

Lacrimal and jugal.—Only the right lacrimal and part of the corresponding jugal are preserved. In dorsal and lateral views Figs. 2 View Fig , 5 View Fig ), the lacrimal is visible on the anterior margin of the antorbital process. In ventral view, the triangular lacrimal occupies about 50% of the surface of the orbit region ( Fig. 6 View Fig ). The suture with the jugal is not visible. Only the base of the styliform portion of the jugal is preserved, located medial to the antorbital notch and displaying a concave lateral surface. Palatine and pterygoid.—The maxilla-palatine suture is difficult to follow, only discernable in its medial portion where the suture is directed anterolaterally ( Fig. 6 View Fig ). The anterior tips of right and left palatines are widely separated (54 mm) as in most other extant delphinoids. The robust ridge of the palatine directed posteromedioventrally and marking the limit between the palate and the orbit/pterygoid sinus region is keeled and more prominent than in extant phocoenids, although it is not as sharp as in Septemtriocetus . In the latter, this ridge has been proposed to correspond to the anterior limit of a lobe of the pterygoid sinus ( Lambert 2008) . Considering the presence of this oblique ridge in extant monodontids, which are known to lack an anterior sinus ( Fraser and Purves 1960) , alternatively it may mark the origin of part of the pterygoid muscles involved in the closure of the mandibles (for delphinids see Seagars 1982). Only a small part of the lateral lamina of the palatine is preserved. Although both pterygoids are lost, the well-preserved medial part of the right palatine provides a rough estimate of the palatine-pterygoid suture and of the extent of the pterygoid sinus in this area. The pterygoid sinus fossa excavates the palatine up to the level of the antorbital notch, whereas the sinus is more posterior in extant phocoenids (and some extinct taxa like Septemtriocetus ). A few small pockets in the dorsal plate of the palatine anterior to each choana presumably correspond to extensions of the pterygoid sinus system.

Parietal.—Only a short portion of the thin parietal is preserved on the mediodorsal wall of each temporal fossa. The wider dorsal exposure of the left parietal in this area ( Fig. 2 View Fig ) is almost certainly an artefact introduced during reconstruction of the skull and/or post-mortem deformation.

Squamosal.—The zygomatic process is proportionally longer than in extant phocoenids and the extinct Salumiphocaena . In lateral view, this process has a rectangular outline ( Fig. 5 View Fig ). The fossae for the sternomastoideus muscles, deeper than in extant phocoenids, occupy more than two thirds of the lateral surface of the process. The postglenoid process is a short and rounded protuberance, more prominent than in Septemtriocetus . The distance between the postglenoid process and the spiny process is longer in the latter, corresponding to a posterior portion of the tympanosquamosal recess (for the middle sinus see Fraser and Purves 1960) that is larger than in Brabocetus gigaseorum . The mandibular fossa is proportionally narrower, less rounded than in Septemtriocetus , and medially margined by a wider and longer anterior part of the tympanosquamosal recess, on a broad medial flange along the zygomatic process ( Figs. 3C View Fig , 7 View Fig ). Between the zygomatic process and the squamosal plate, a deep and narrow squamosal fossa forms the floor of the temporal fossa. In extant phocoenids, the shallower squamosal fossa is more open laterally, and not, or only slightly concave longitudinally. Present in the holotype of Septemtriocetus bosselaersi , the fossa is nevertheless posteriorly shorter than in Brabocetus gigaseorum .

Exoccipital.—The occipital condyles protrude only weakly from the posterior wall of the braincase and a shallow dorsal condyloid fossa is present ( Fig. 3B View Fig ). The long axis of the left condyle diverges more from the sagittal plane than on the right side (difference of ca. 5°). In addition, the left exoccipital is wider than the right exoccipital along its ventral margin. Not due to reconstruction approximations, this asymmetry may indicate either an asymmetrical position, or even preferential directions of movement, for the head relative to the vertebral column (a hypothesis that should be tested with a larger sample, including extant phocoenids). The foramen magnum is subcircular. As in Septemtriocetus and most other fossil phocoenids, a shallow depression is present on the anterior surface of the paroccipital process, probably corresponding to the fossa for the posterior sinus. The fossa is deeper in Haborophocoena minutus ( Ichishima and Kimura 2009) and extant phocoenids, in which it is sometimes only closed posteriorly by a thin, translucent plate of exoccipital.

Basioccipital.—The left basioccipital crest is preserved. In lateral view, a shallow notch cuts the crest before a transversely swollen region anterior to the jugular notch. As in Septemtriocetus , a subcircular depression is present on the medial wall of the basioccipital crest, next to the jugular notch ( Fig. 7 View Fig ), probably for the scalenus medius muscle, which when activated draws the head downward ( Lambert 2008). In ventral view, the angle drawn by the two basioccipital crests is roughly estimated at 45–50°.

Basisphenoid.—The basisphenoid crest is damaged by erosion. Its lateral wall is slightly excavated at its base, but not as much as in Septemtriocetus and extant phocoenids. If present, the basisphenoidal sinus (sensu Mead and Fordyce 2009; basisphenoid lobe of the pterygoid sinus sensu Ichishima and Kimura 2005 , 2009; Lambert 2008) was poorly developed.A deeper fossa is reported in Piscolithax longirostris , and the condition in Brabocetus gigaseorum more closely matches the condition in Australithax , Haborophocoena toyoshimai , Lomacetus , and Piscolithax tedfordi ( Barnes 1984; Muizon 1984, 1988b; Ichishima and Kimura 2005).

Alisphenoid.—Better preserved on the left side of IRSNB M.2171, the foramen ovale is small (maximum diameter 7 mm). It is bordered laterally by a short trough that held the mandibular nerve V3 ( Fig. 7 View Fig ). The anterior ridge of the aforementioned trough corresponds to the posterior limit of a wide and shallow fossa for the pterygoid sinus.

Table 1. Measurements (in mm) on the skull of Brabocetus gigaseorum gen. et sp. nov. IRSNB M. 2171 (holotype). e, estimate; + incomplete.

| Condylobasal length | e300 |

|---|---|

| Rostrum length as preserved | +66 |

| Distance between antorbital notch and posterior end of alveolar groove | 33 |

| Width of rostrum at base | e73 |

| Width of premaxillae at rostrum base | 40 |

| Longitudinal distance between nuchal crest and antorbital notches | 122 |

| Longitudinal distance between anterior margin of bony nares and antorbital notches | 57 |

| Distance between premaxillary foramen and anterior margin of bony nares | 44 |

| Preorbital width of skull | e115 |

| Postorbital width of skull | e148 |

| Maximum width of premaxillae on cranium | 52 |

| Width of bony nares | 40 |

| Maximum width of fossae for nasals | 37 |

| Length of orbit | e50 |

| Length of temporal fossa | e75 |

| Distance between anterior tip of zygomatic process of squamosal and ventral tip of postglenoid process | 42 |

| Distance between jugular notches | e85 |

| Width of occipital condyles | 74 |

| Maximum width of right occipital condyle | 29 |

| Width of foramen magnum | 37 |

| Height of foramen magnum | 36 |

| IRSNB |

Institut Royal des Sciences Naturelles de Belgique |

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.

|

Kingdom |

|

|

Phylum |

|

|

Class |

|

|

Order |

|

|

SubOrder |

Odontoceti |

|

InfraOrder |

Delphinida |

|

SuperFamily |

Delphinoidea |

|

Family |

|

|

Genus |