Halistemma cupulifera Lens & van Riemsdijk, 1908

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/ 10.11646/zootaxa.3897.1.1 |

|

publication LSID |

lsid:zoobank.org:pub:CB622998-E483-4046-A40E-DBE22B001DFD |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/03FC87BC-FFC3-FFDA-FF62-AA596604FA17 |

|

treatment provided by |

Felipe |

|

scientific name |

Halistemma cupulifera Lens & van Riemsdijk, 1908 |

| status |

|

Halistemma cupulifera Lens & van Riemsdijk, 1908 View in CoL

Halistemma cupulifera Lens & van Riemsdijk, 1908, p. 85 View in CoL , pl. XVI; Pugh & Youngbluth, 1988, p. 10, fig. 6C.

Stephanomia cupulita Kawamura, 1954, p. 112 .

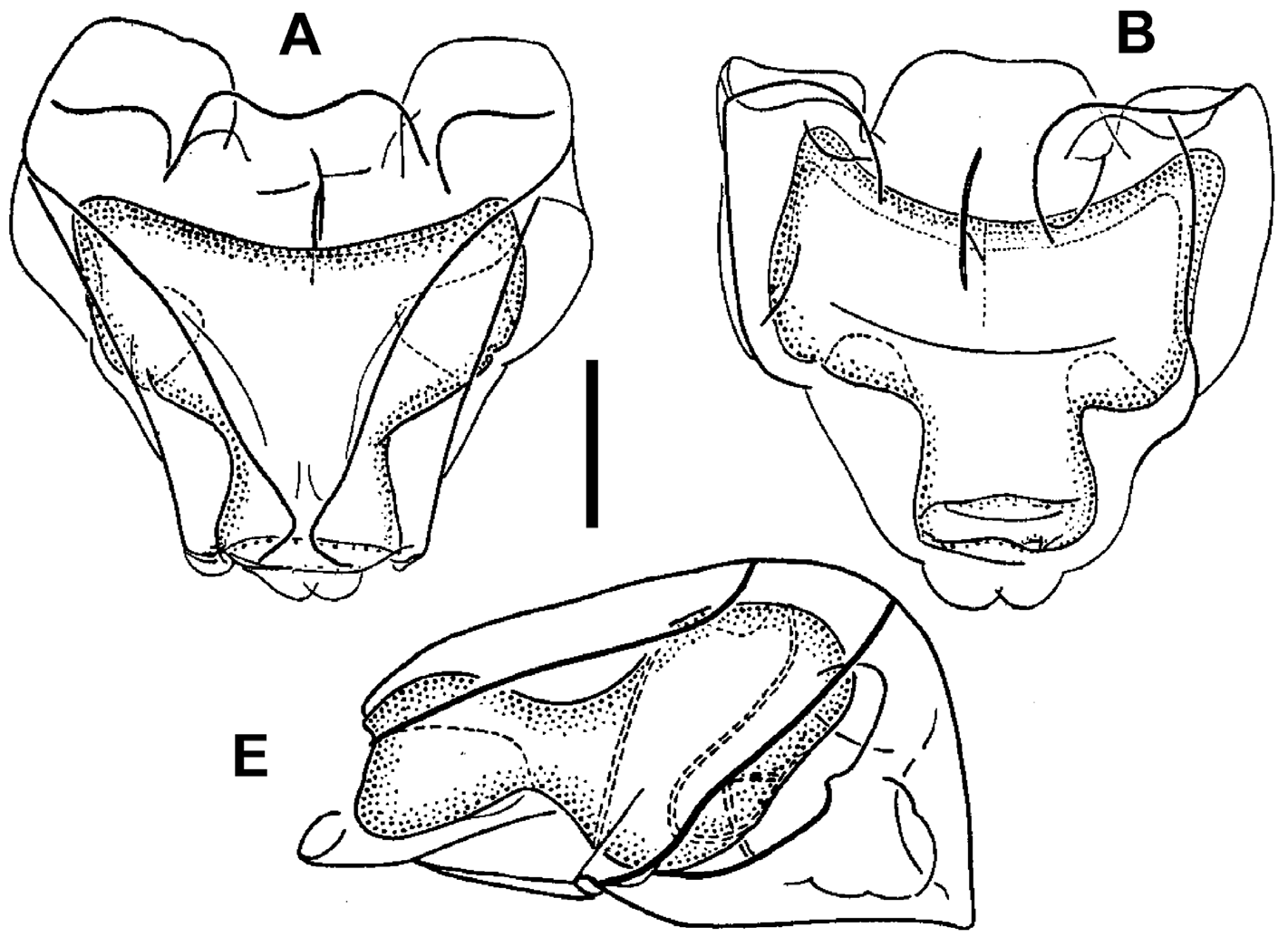

Halistemma rubrum Totton, 1954 View in CoL (in partim) Text—fig. 16, A, B, E.

? Paragalma birsteini Margulis, 1976, p. 1244 , figs. 1–3.

Diagnosis: Basic Halistemma ridge pattern on nectophores, with pair of complete vertical-laterals and laterals arising from upper laterals and ending just above the large lateral ostial processes. Up to five types of bract. Tentilla with small, cup-shaped involucrum covering at most the first two spirals of the cnidoband, and a large cupulate terminal process to the terminal filament.

Material examined:

JSL II Dive 1450 – CG4 28 August 1987 24°38.8'N 83°45.3'W depth 683 m GoogleMaps

Atlantis 2 St. 101 25 June 1978 40°04.6'N 54°31.4'W depth unknown

Discovery St. 3185 14 November 1954 40°47'N 12°05'W depth 0 m

Discovery 7089#13 14 November 1969 17°48'7'N 25°28.7'W depth 515–600 m

Holotype: Siboga St. 244. Lat. 4°25.7'S, 130°3.7' E. 2991m. Housed in the Zoölogisch Museum, Amsterdam, COEL 4516 . GoogleMaps

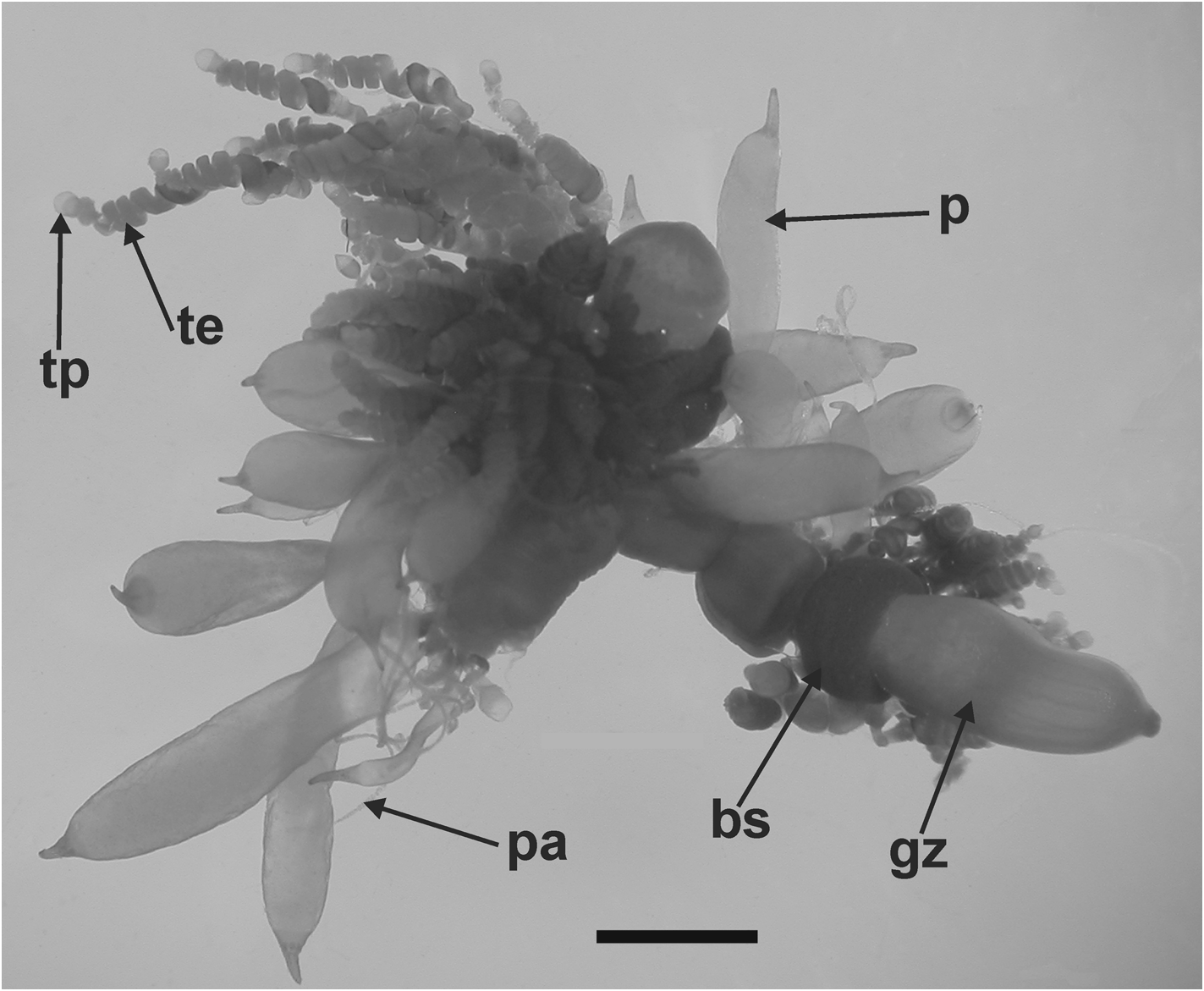

Description: This description will be based mainly on the JSLII Dive 1450 specimen ( Figure 26 View FIGURE 26 ), which consisted of the stem with the pneumatophore, the largely denuded nectosome and parts of the siphosome, together with some detached nectophores and bracts.

Pneumatophore: The pneumatophore measured 1.7 mm in length, and 0.6 mm in diameter. There was a distinct patch of cells at the apex that may have been pigmented. Whatever pigmentation there might have been had leeched away during preservation.

Nectosome: The nectophores were budded off on the dorsal side of the stem.

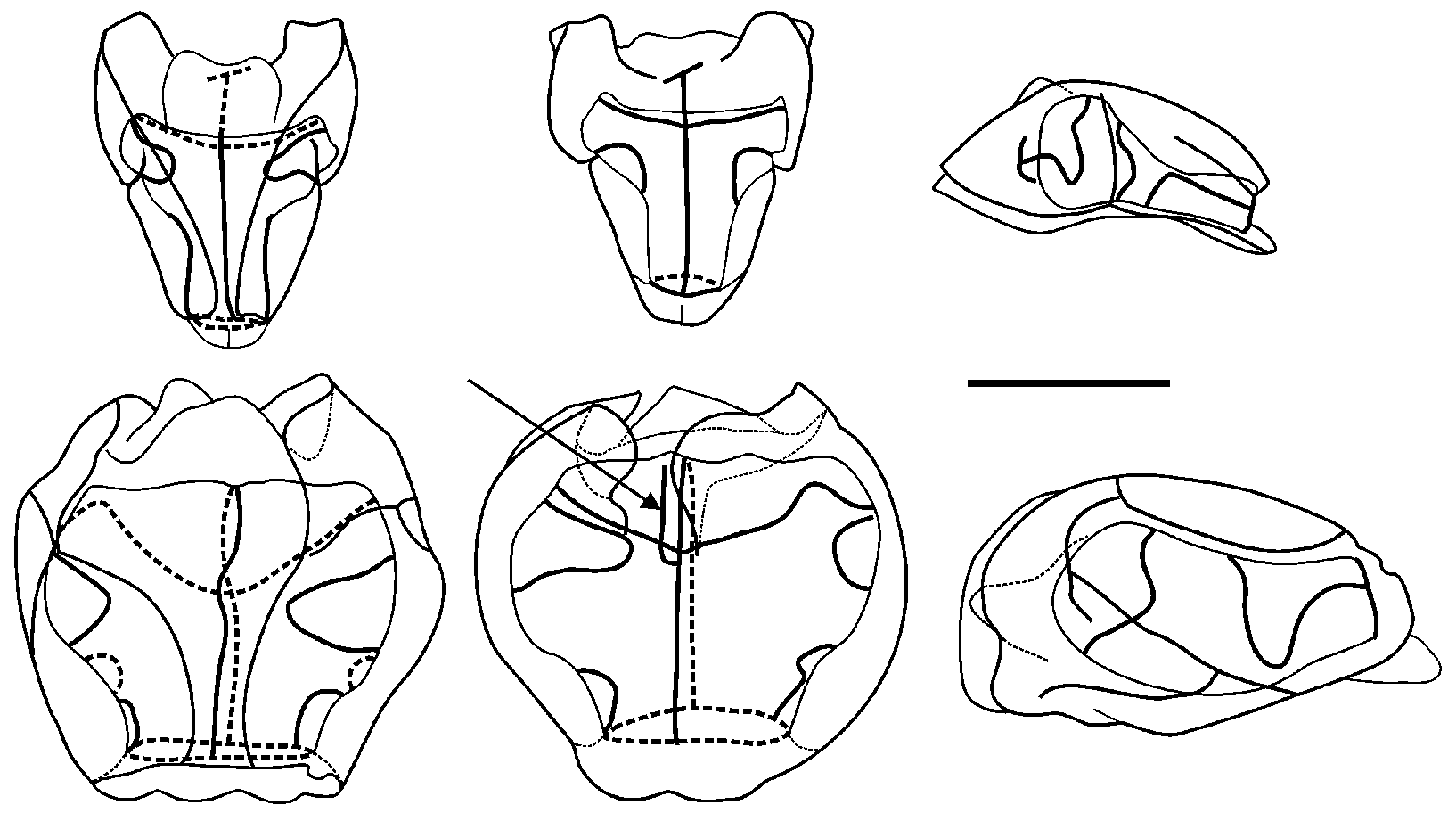

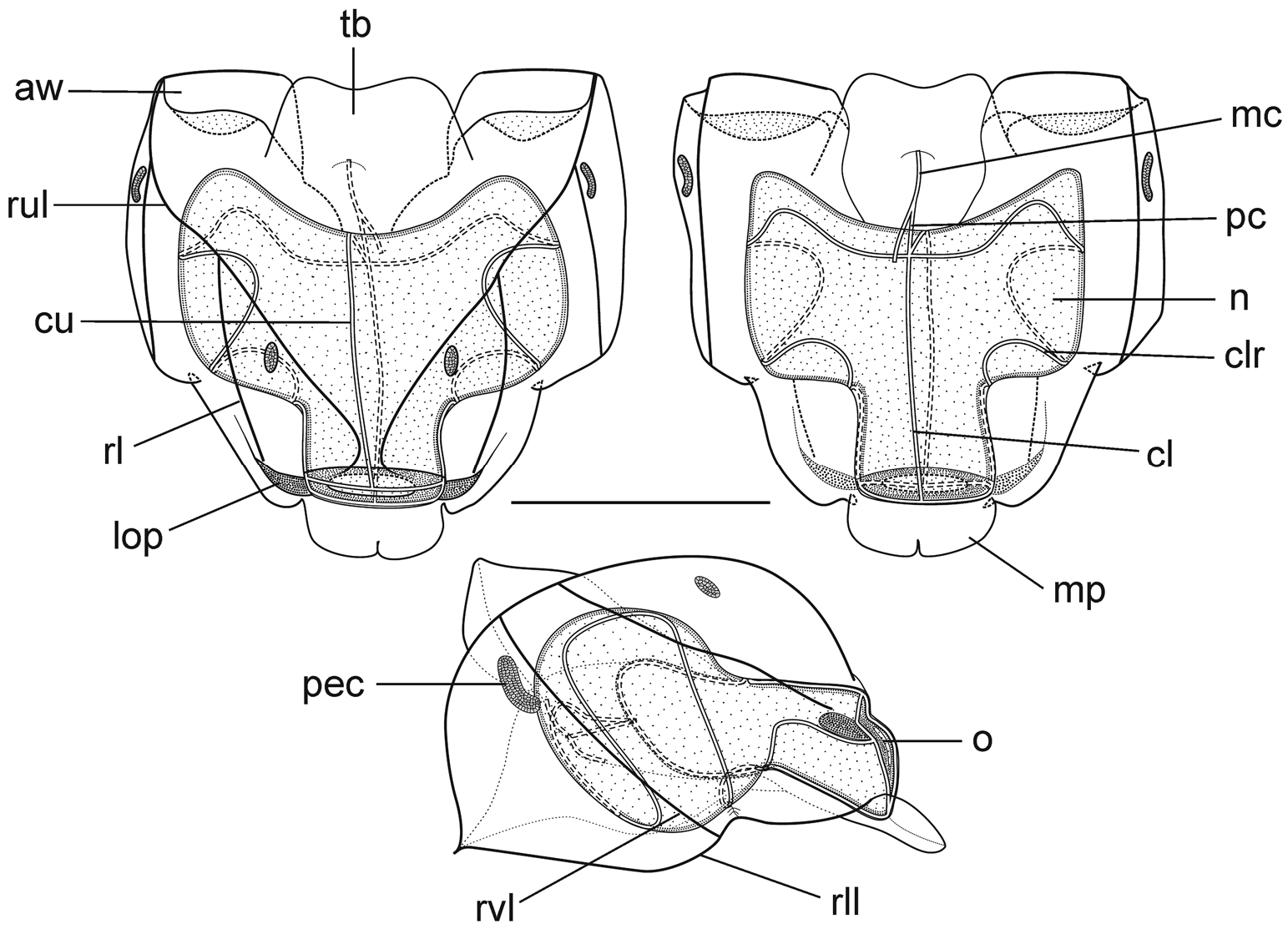

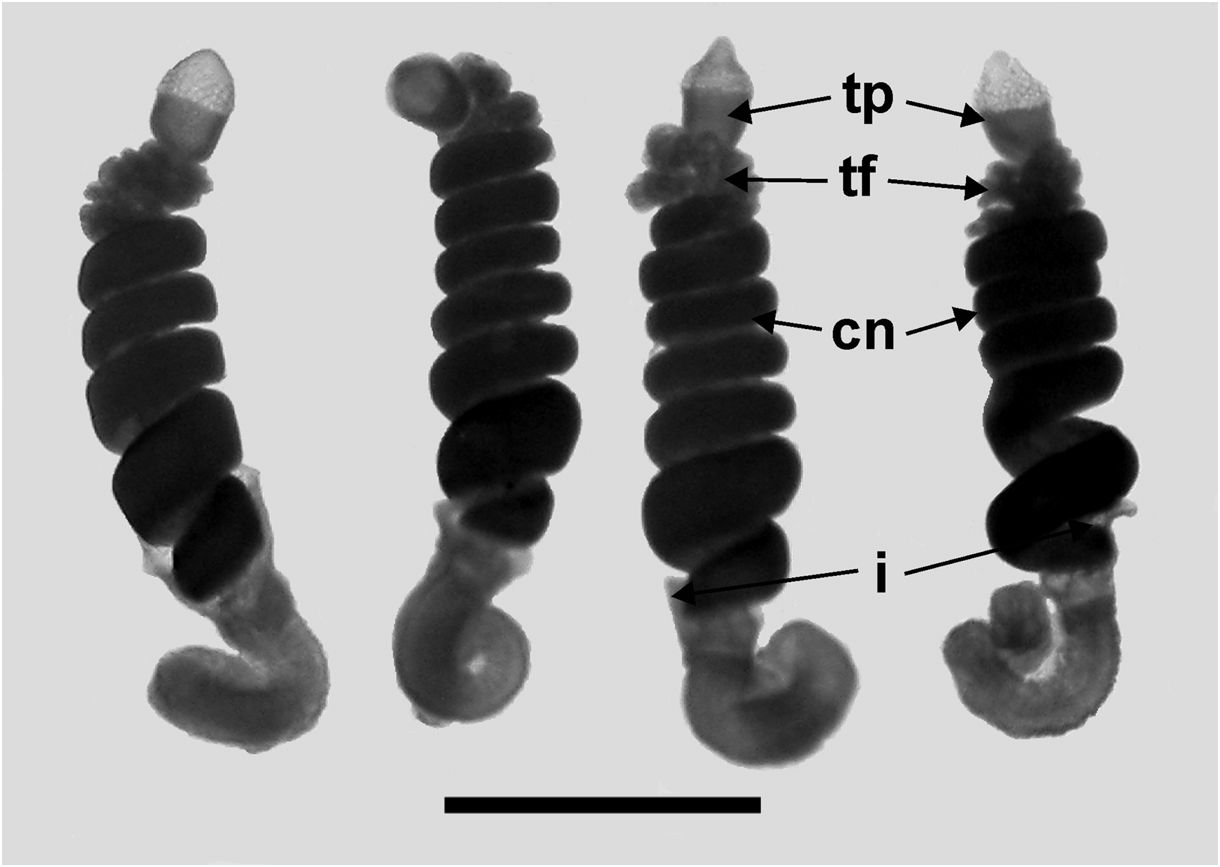

Nectophores: Eighteen detached nectophores were present in association with the JSLII Dive 1450 specimen, together with some nectophoral buds, at varying stages of development, and attachment lamellae. Detached nectophores ranged in size from 1.9 x 1.7 mm (height x width) to 9.5 x 9.0 mm. The upper view of the largest nectophoral bud ( Figure 27 View FIGURE 27 ) clearly showed the upper lateral ridges curving outwards just above the ostium, and also giving rise to the lateral and vertical lateral ridges. The relatively enormous lateral ostial processes had numerous elongate nematocysts projecting out from them. Both the axial wings and the central thrust block were only slightly developed, and there was no obvious mouth plate.

In the smaller, younger nectophores ( Figure 28 View FIGURE 28 ) the central thrust block was still quite flat and underdeveloped, but the axial wings had considerably enlarged and extended well beyond it. In the ostial region, a mouth plate had begun to develop, which was slightly emarginated in the mid-line. The lateral ostial processes were still relatively large, but most of the nematocysts by now had been lost, at least in the preserved material, and so these processes were covered in small plate-like cells. No nematocysts were ever seen in this region on fully developed nectophores. Totton (1965), for Halistemma striata , described these lateral processes as ostial chromatophores, but clearly this was not their original function and, in addition, they do not appear to be pigmented. Whether, once the nematocysts are lost, they become sites of bioluminescence is not clear. However, there were two pairs of oval, occasionally elongate, patches of ectodermal cells on the upper lateral sides of the nectophore that almost certainly were sites of bioluminescence. On pair lay close to the junction of the upper lateral and vertical lateral ridges, on the upper side of the latter; and the other lay close to the upper lateral ridges, between them and the lateral ridges. These patches were easily abraded and generally were not seen in the net collected material.

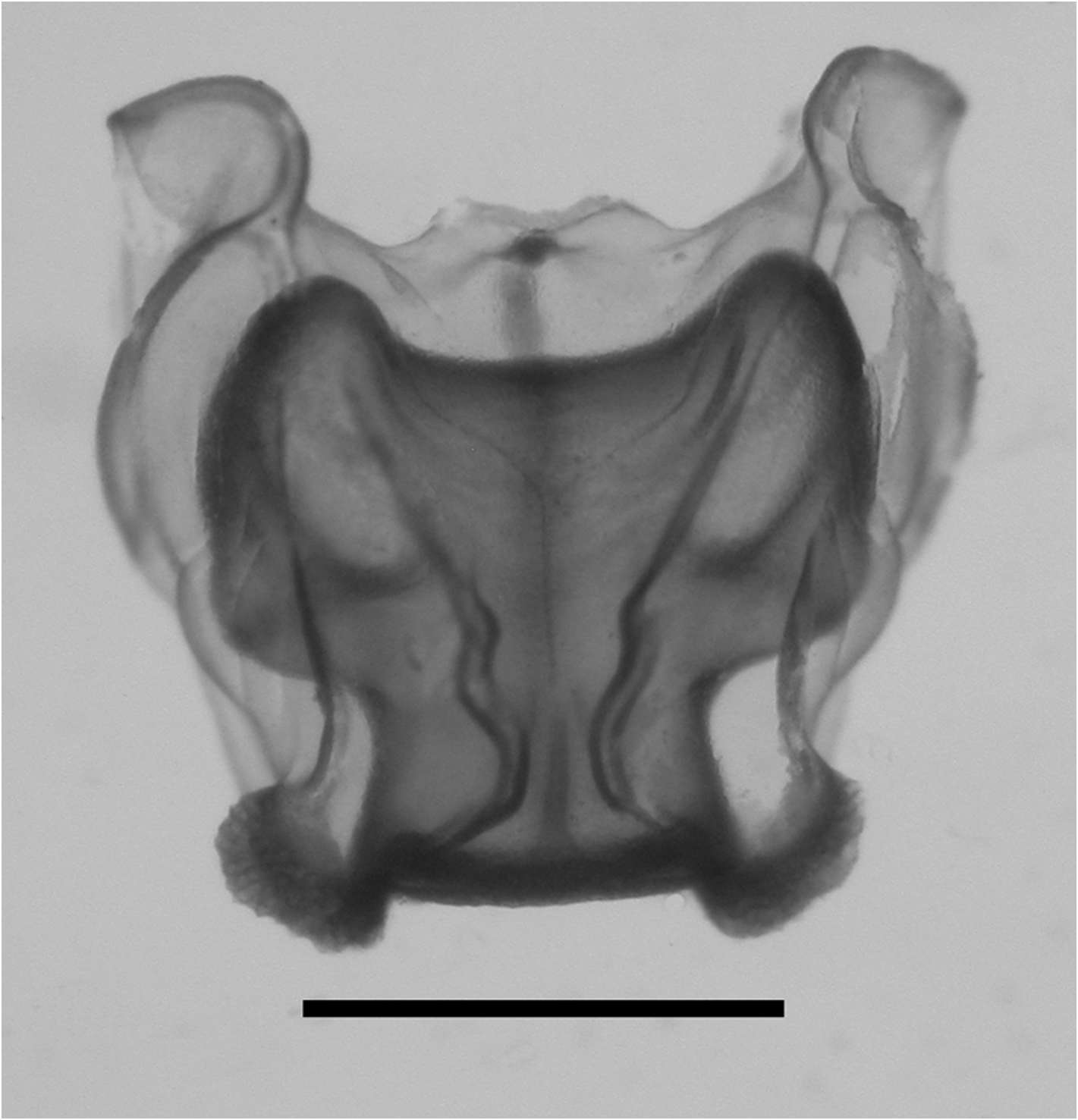

As the nectophores increased in size the central thrust block became more and more developed and ultimately reached to the same level or slightly above the now squared-off, slightly outward-sloping axial wings ( Figure 29 View FIGURE 29 ). The mouth plate also increased in size, but still remained only slightly emarginated in the midline. The typical Halistemma arrangement of the ridges on the nectophores of H. cupulifera was present. The upper lateral ridges ( Figure 29 View FIGURE 29 ) ran from the apical margins of the axial wings distally toward the ostium. At first they were widely apart, but after they had given rise to the vertical lateral ridges they curved inward and continued obliquely toward the midline. Their closest approach was slightly above the ostium, but then they curved out and continued laterally, gradually petering out. The lateral ridges branched from the upper lateral ridges at approximately half the latter's length (but higher up in the younger nectophores) and ran obliquely down the lateral surfaces of the nectophore towards the ostium. However, they also petered out, and on a level with the upper laterals, ended just above the lateral ostial processes. The vertical lateral ridges extended from the upper laterals, at approximately the level of the top of the nectosac in mature nectophores ( Figure 29 View FIGURE 29 ), and well above the nectosac in the younger ones ( Figure 28 View FIGURE 28 ), obliquely downwards and almost parallel to the laterals until they joined the lower lateral ridges. These lower lateral ridges ran along the entire length of the lower lateral edge of the nectophore from the outer margins of the axial wings, where they joined with the apico-laterals, to below the ostium where the joined with the lateral margins of the mouth plate. The proximal and distal parts of these ridges slightly overlapped each other at about one-third the height of the nectophore. There were no distinct ridges on the lower surface of the nectophore; however, in the preserved material folds ran down the inner apices of the axial wings to just above the upper-mid line of the nectosac below the region of the central thrust block.

The ascending and descending branches of the mantle canal, on the proximal median surface of the nectophore, were of almost equal length, so the pedicular canal arose at its mid-length and extended down to the nectosac. There it gave rise to all four radial canals. The courses of the upper and lower canals were straight. The lateral radial canals extended out laterally and formed a loop before reaching the lateral margins of the nectosac. They then looped up onto the upper side of the nectosac, and then back down the lateral surface and onto the lower surface, before returning back to the lateral surface of the nectosac and curving round to run directly to the lateral margins of the ostium, where they joined the ring canal.

Siphosome: In all the specimens examined the siphosome was greatly contracted and it was not possible to determine accurately the organisation of the individual cormidia.

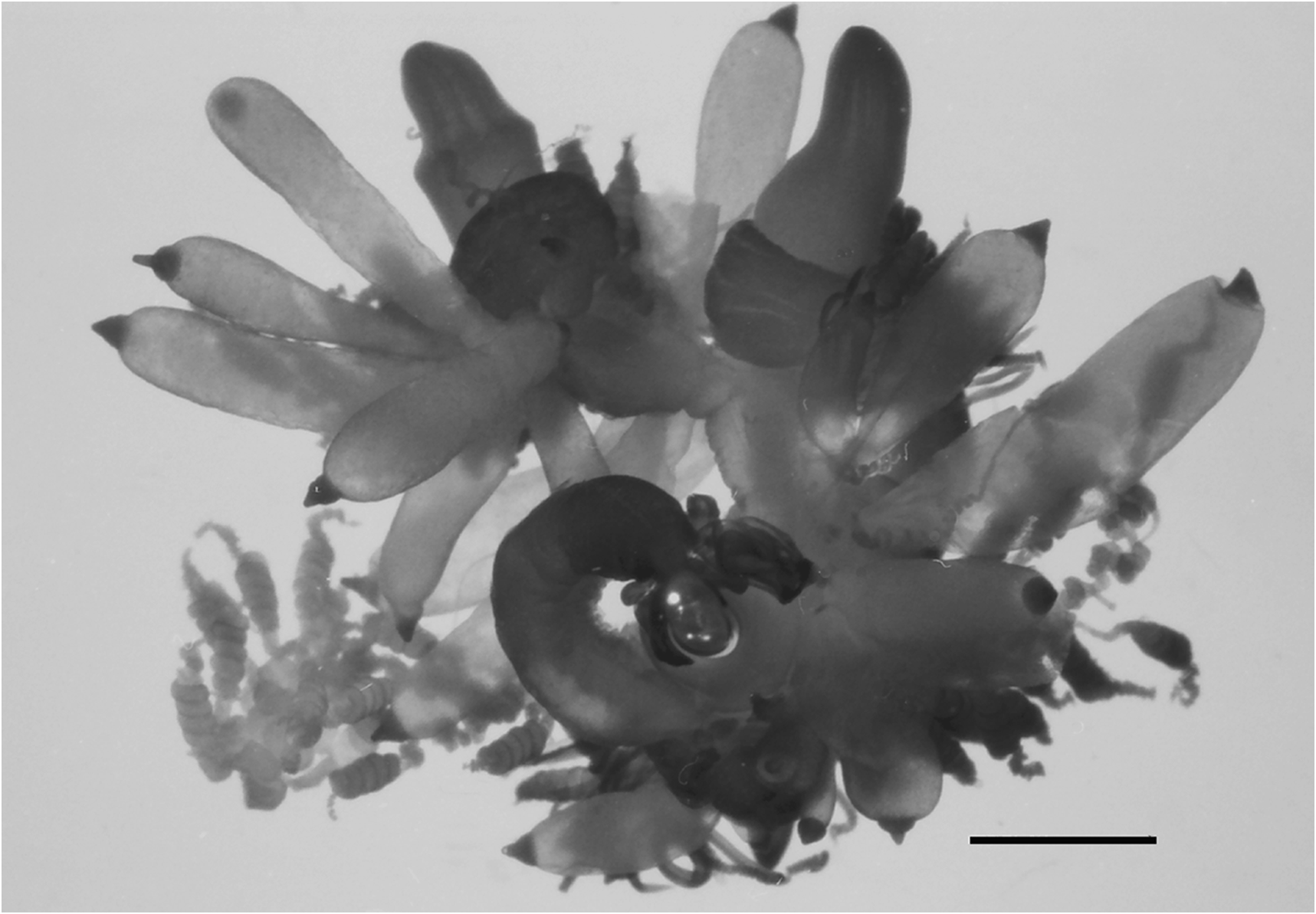

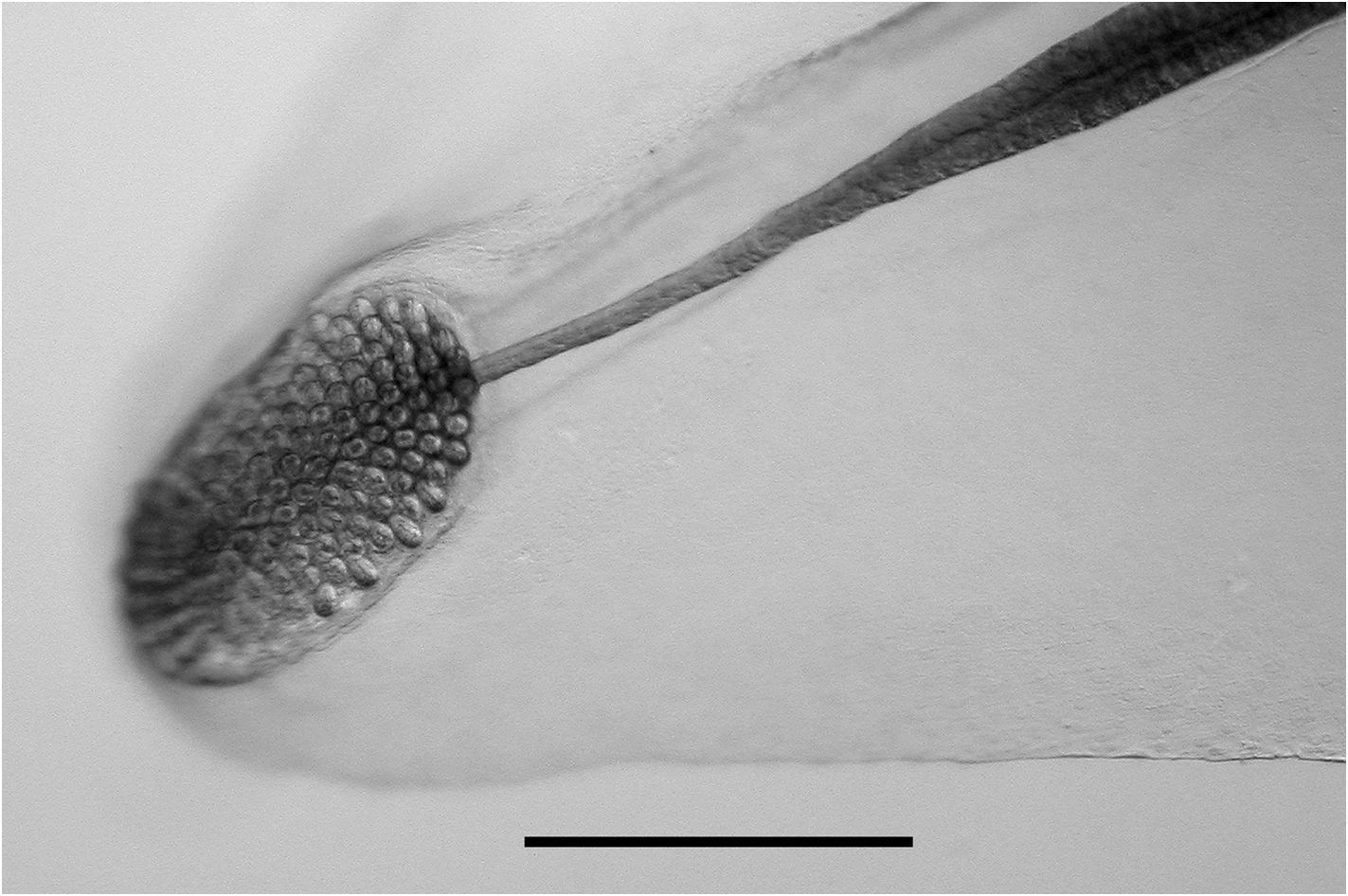

Bracts: Fifty-seven, generally foliaceous bracts were found with the JSLII Dive 1450 specimen and these could be divided into five categories on the basis of their general morphology, which included the number of lateral teeth and ectodermal cell patches on the outer surface. The latter were undoubtedly sites of bioluminescence, as Mr. Peter David observed brilliant bluish bioluminescence being emitted by them when he hand-collected the Discovery St. 3185 specimen. The bracteal canal lay just within the lower surface of the bract for most of the length, only entering the mesogloea and sloping up towards the upper surface close to the distal end. The canal ended below a cup-shaped oval hollow on the upper surface that, in the younger bracts at least, was filled with tightly packed elongate nematocysts ( Figure 30 View FIGURE 30 ). Like those on the lateral ostial processes on the nectophore, these nematocysts had generally disappeared in the fully-grown bracts.

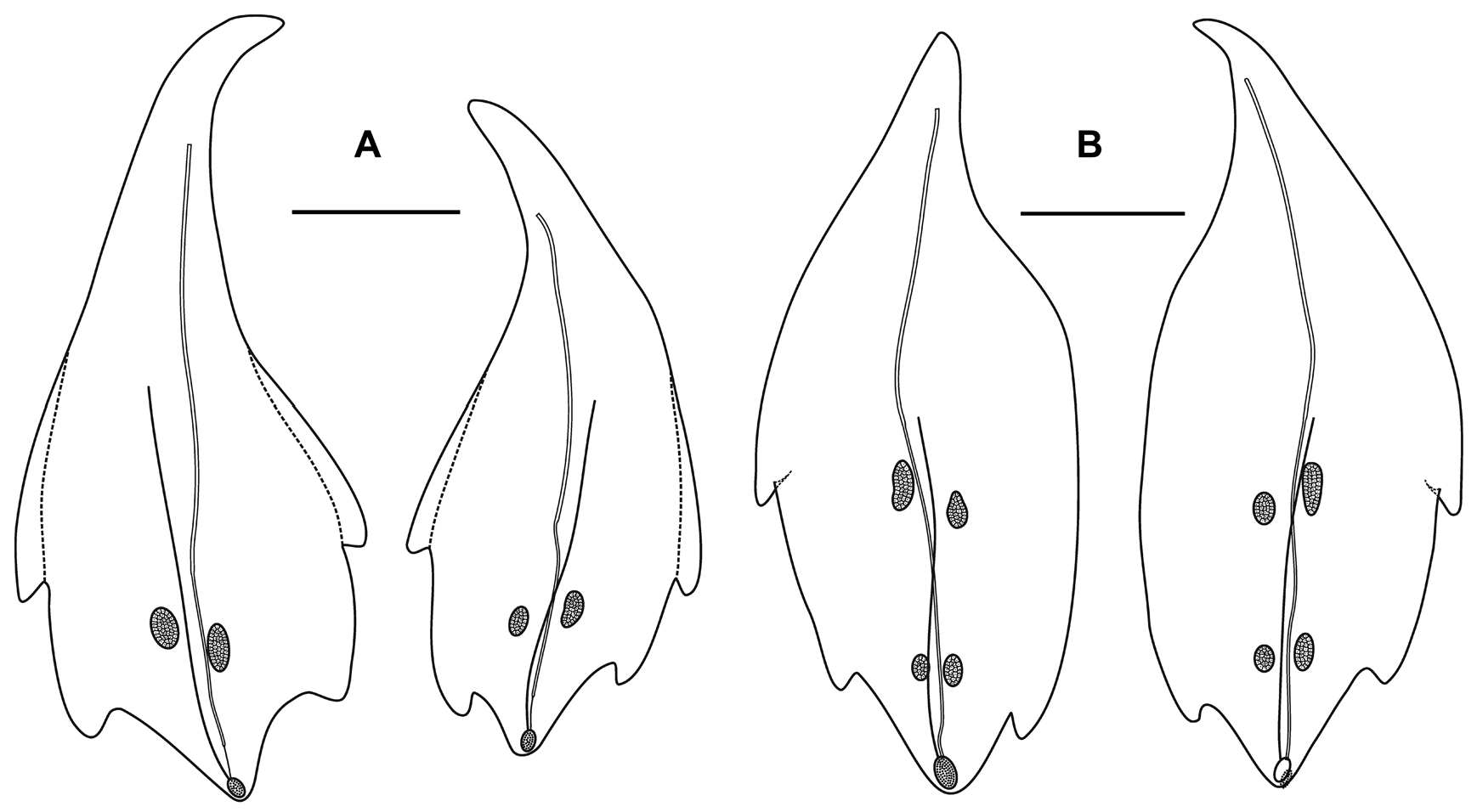

Type A —Twenty-eight bracts of this type were found in association with this specimen, the most numerous bracts present ( Figure 31 View FIGURE 31 ). These bracts were elongate, with a distinctly tapered proximal end that bent toward the inner side, and were present in enantiomorphic pairs. They ranged in length from 14.5 to 24 mm and from 6 to 12 mm in width at the widest part (between the proximal pair of lateral teeth). They bore two distinct pairs of lateral teeth, and a median ridge on the upper surface that was most distinct in the distal half of the bract. The mesogloea was markedly thickened in the proximal part of the bract, where the lower part of the bract showed no concavity. At approximately the same level as the origin of the canal the thickness of the mesogloea began to reduce, at first only in the central part of the lower surface, but then gradually the concavity on that side widened and deepened so that at the distal end of the bract the mesogloea was very thin. The bracteal canal remained in contact with the lower wall throughout most of it length, but at a level just proximal to the proximal pair of teeth, it showed a marked narrowing. Close to its distal end the canal penetrated into the mesogloea and ran obliquely toward the upper surface. There was only one pair of oval ectodermal patches, toward the distal end of the upper side of the bract, which were slightly misaligned and occasionally quite elongate.

Type B —Eleven bracts of this kind were present in enantiomorphic forms ( Figure 31 View FIGURE 31 ). They were also quite large, elongate and asymmetrical, measuring from 9.2 to 22.5 mm in length and from 6 to 8.5 mm in width. There were three lateral teeth. A single more proximal one on the outer lateral edge of the bract, which extended slightly on to the upper surface, and an asymmetric pair of more distal lateral ones. There were two pairs of ectodermal cell patches. A median ridge stretched from approximately the mid-length of the upper surface of the bract to almost the distal end. The bracteal canal, which originated closer to the proximal end of the bract than for the Type A bracts, but still some distance from it, had a similar arrangement as found in the Type A bracts; thinning on a level with the proximal end of the median ridge; entering the mesogloea close to the distal tip; and running up to end below the cupulate structure on the upper side of the bract.

Type C —Nine bracts of this type were found ( Figure 32 View FIGURE 32 ). This asymmetrical type appeared to be intermediate in form between the Type A and B bracts. They were smaller with two pairs of lateral teeth, the more distal pair being very asymmetrically arranged, and just one pair of ectodermal patches. They ranged from 8 to 17 mm in length and from 5.5 to 11.5 mm in width. The bracteal canal extended almost to the proximal point of the bract and in young bracts, the canal remained thick for almost the entire length, tapering only towards the distal end when it entered the mesogloea. In the larger bracts of this type, the canal thinned at the same level as the proximal end of the median dorsal ridge.

Type D —Seven, very rounded bracts of this type were found. They did not seem to be present in enantiomorphic pairs and appear to be characteristic for this species ( Figure 32 View FIGURE 32 ). They measured from 10.5 to 15 mm in length and from 10 to 14 mm in width. The mesogloea of the proximal end of the bract was extremely thick, but its thickness rapidly decreased on the lower side, and it remained relatively thin for most of the length of the bract. This, combined with the fact that the bracts were extremely concavo-convex, resulted in most of the bracts observed being folded in two longitudinally. There was one pair of rounded lateral teeth that extended beyond the median distal point of the bract in upper view. They possessed two small pairs of ectodermal cell patches, which were quite even in size and shape (small ovals) on all bracts. The bracteal canal originated almost on the upper side of the bract, running down, within a shallow central furrow, the proximal end and then along the lower surface of the bract until the distal end where it entered the mesogloea as in the other bract types. In younger bracts, the canal remained thick for almost the entire length, tapering only at the point of sloping into the mesogloea where as in older bracts, the canal thinned just over a quarter of the way down from the proximal end. A median lateral ridge also started at this point and petered out over the distal cupulate process, as with the other types of bract.

Type E —Only two small bracts of this type were found ( Figure 32 View FIGURE 32 ). They measured 9 and 7 mm in length and 13.2 and 9 mm in width and were present in the same asymmetrical morph. The proximal ends of the bracts were extremely pointed and the mesogloea much thickened in that region. However, at about one third the length of the bract the mesogloea suddenly thinned on the inner side resulting in a marked change of direction of the bracteal canal. This canal remained thick along almost its entire length, only tapering when it entered the mesogloea distally. This might indicate that the bracts were not fully developed, as was seen for some of the other types of bract. There was a pair of distal lateral teeth, but only one more proximal one on the outer lateral side. The median ridge on the upper side ran from just under half the length of the bract, just proximal to the level of the proximal tooth. There was one pair of quite elongate ectodermal cell patches on the upper surface of each bract.

Bigelow (1911), in his description of Halistemma foliacea under the name Stephanomia amphitridis , noted that the bracts on his specimens appeared to be arranged in four or five irregular rows. He also mentioned dorsal, lateral and ventral types of bract. Kawamura (1954), who re-examined Bigelow's material, considered that there were five rows, one dorsal and two laterals on each side. Assuming that the latter two types were different and occurred in enantiomorphic pairs on either side of the stem, then this would suggest five rows of bracts of three types. It is difficult to reconcile that with our present findings of five types of bract. It is very likely that the Type D bracts represent the dorsal ones, as they did not appear to occur in enantiomorphic pairs. It is possible that the Type C bracts, with four lateral teeth and a pair of ectodermal patches on the upper surface, may be a young form of the Type A bracts, which also share the same characters. However, although both the Type B and Type E bracts have three lateral teeth, the former has two pairs of ectodermal patches, while the latter only has one. As noted above the two Type E bracts where small and probably not fully developed, but the absence of the second pair of ectodermal patches is striking.

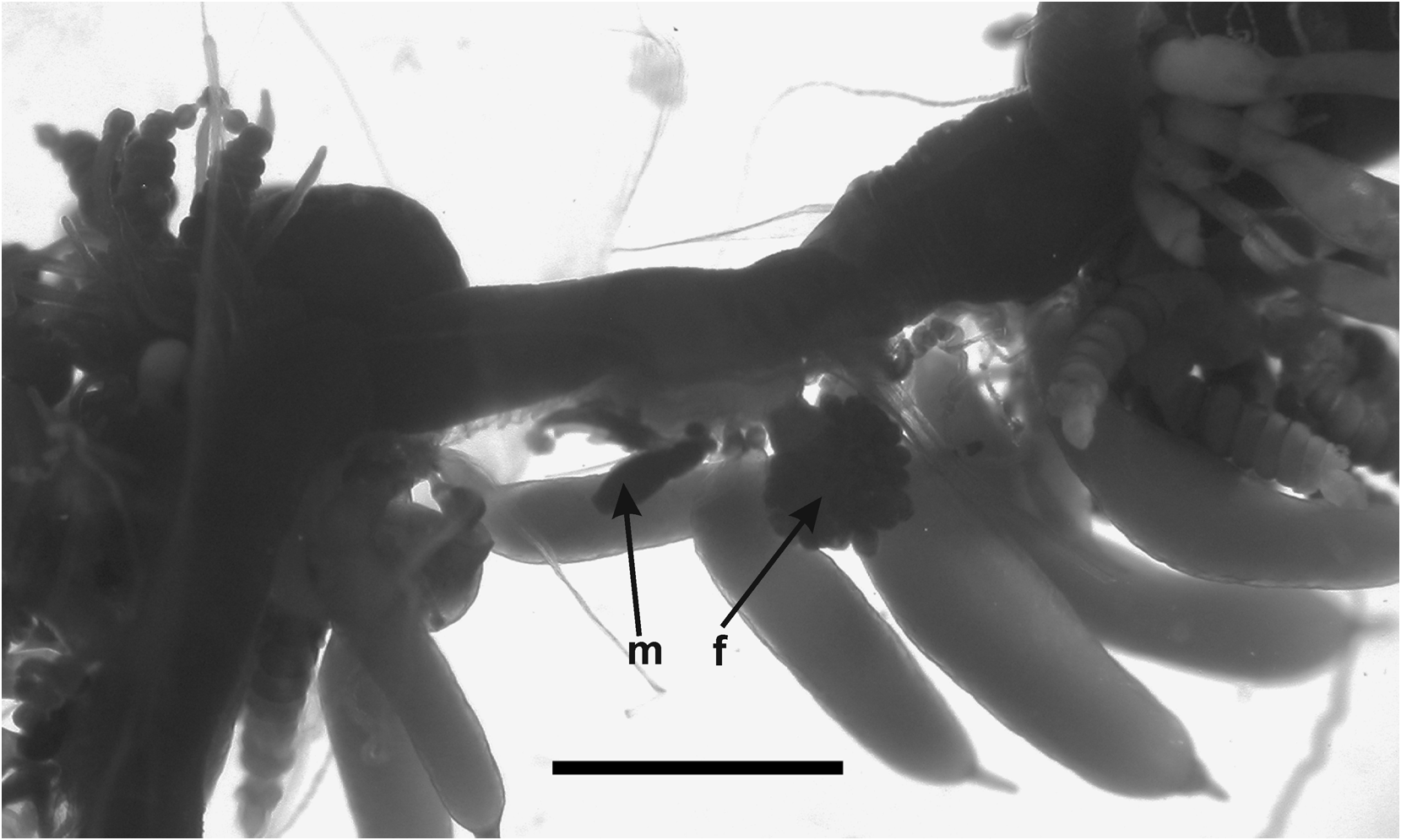

Gastrozooid and tentacle: The gastrozooids, up to 6 mm in length, showed no particular diagnostic features ( Figure 33 View FIGURE 33 ). There was a cupulate basigaster proximally, a variously expanded, central stomach region, and an extremely variable distal proboscis. Any pigmentation that might have been present in life had been leeched out during preservation.

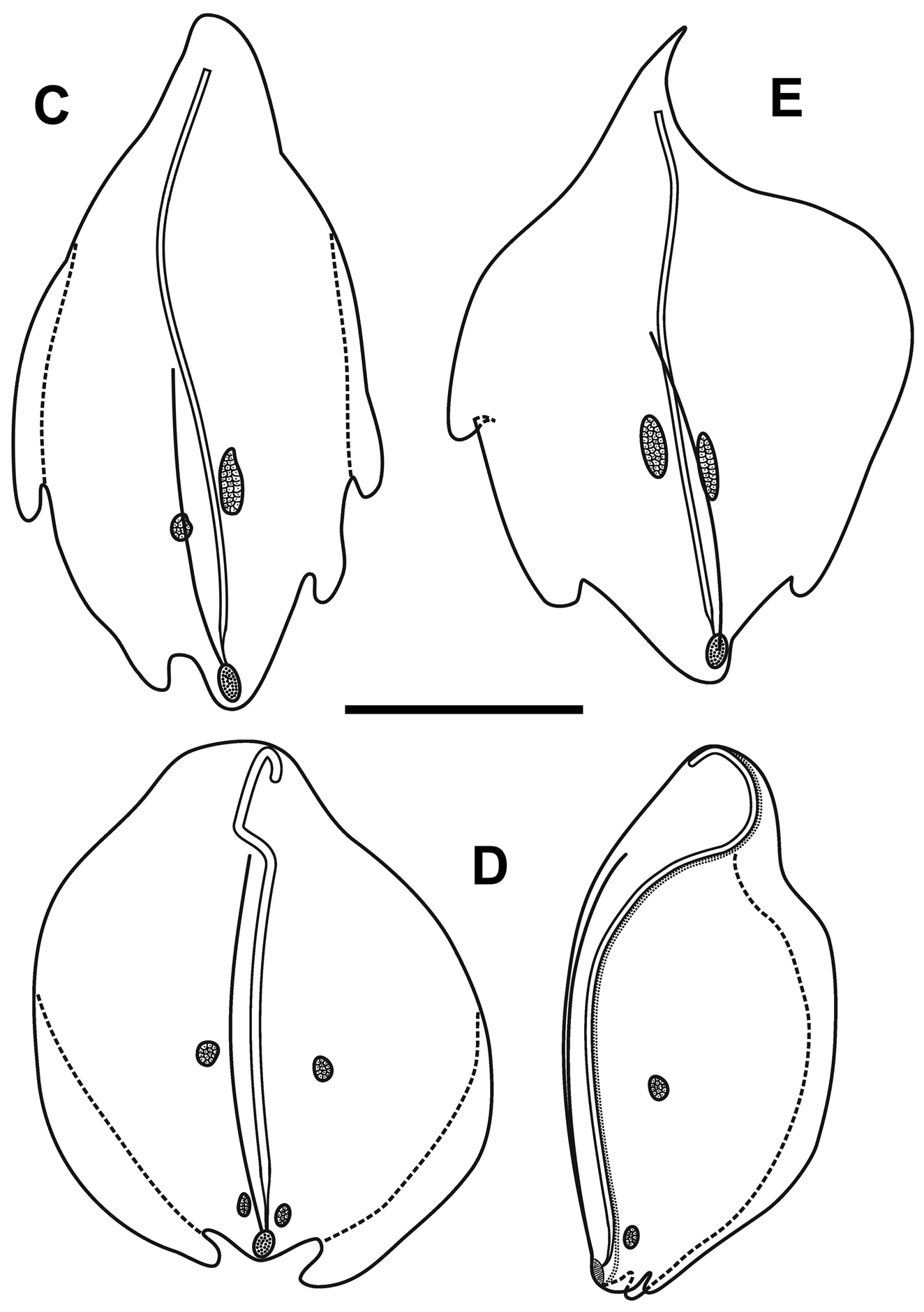

Tentilla: Only the mature tentilla were looked at in detail ( Figure 34 View FIGURE 34 ). They were borne on highly contractile pedicels, at the distal end of which was an involucrum. This involucrum varied in size from a simple enlarged ring around the pedicel to a cup-shaped structure covering at least the first two spirals of the cnidoband. These differences did not appear to be developmental stages, but probably were caused by damage to the fragile structure. The cnidoband had up to seven closely wound spirals, on which two types of nematocyst were found on their outer surfaces. The vast majority of the nematocysts, arranged in many rows, were banana-shaped, measuring c. 48 µm in length and 6.5 µm in diameter. No discharged ones were noted and so their identity was not ascertained, but presumably they were anisorhizas (see Carré, 1971). On either side of these nematocysts, in the most proximal part of the cnidoband, was a single row of stenoteles; there being about 50 on each side. These measured c. 67 µm in length and 26 µm in diameter. Large numbers of c. 12 µm diameter platelets were also apparent in the cnidoband. The terminal filament arose at the distal end of the cnidoband and clearly could reach a considerable length when fully extended. Two types of nematocyst were present, although their exact arrangement was not apparent. These were probably acrophores, which measured 19.5–25 µm in length and 10.5–12 µm in diameter, and desmonemes, c. 25 x 10.5 µm respectively. At the end of the terminal filament was a large cupulate terminal process, which measured 250–315 µm in length and 200–300 µm in diameter. The distal part bore no nematocysts, but was covered in round or ovoid platelets, ranging from 18 to 23 µm in length. The proximal part bore nematocysts similar to those of the terminal filament, but generally smaller. The ratio between the proximal and distal parts of the terminal process was somewhat variable, ranging from c. 2:1 to 1:2.

Palpon: Most of the palpons remained attached to the siphosomal stem fragments of the JSLII Dive 1405 specimen ( Figure 33 View FIGURE 33 ), but a few larger ones were detached and these measured up to 6.3 mm in length and 2.7 mm in diameter ( Figure 35). These larger ones appeared to be filled with a dense amorphous substance, while the younger ones on the stem were more translucent with a milky-white appearance. All had a more or less extended narrow distal proboscis, and a long thin palpacle, attached proximally. Although there was a regular arrangement of the cells on the palpacle, no nematocysts were found on it or, indeed, on the palpon itself.

Gonophore: No gonophores were found with the JSLII 1405 specimen, but the Atlantis 2 St. 101 one showed some developing ones ( Figure 36 View FIGURE 36 ). Both the male and the female gonodendra were attached to a distinct inflation on the ventral side of the siphosome, with the male one anterior to the female. The female gonophores formed a racemose cluster borne on a distinct thickened stalk. Between them were attached two palpons, one of which had broken off, but its peduncle was still visible.

Nectalia stage: None of the specimens examined were at this stage, and no larval bracts or tentilla were observed.

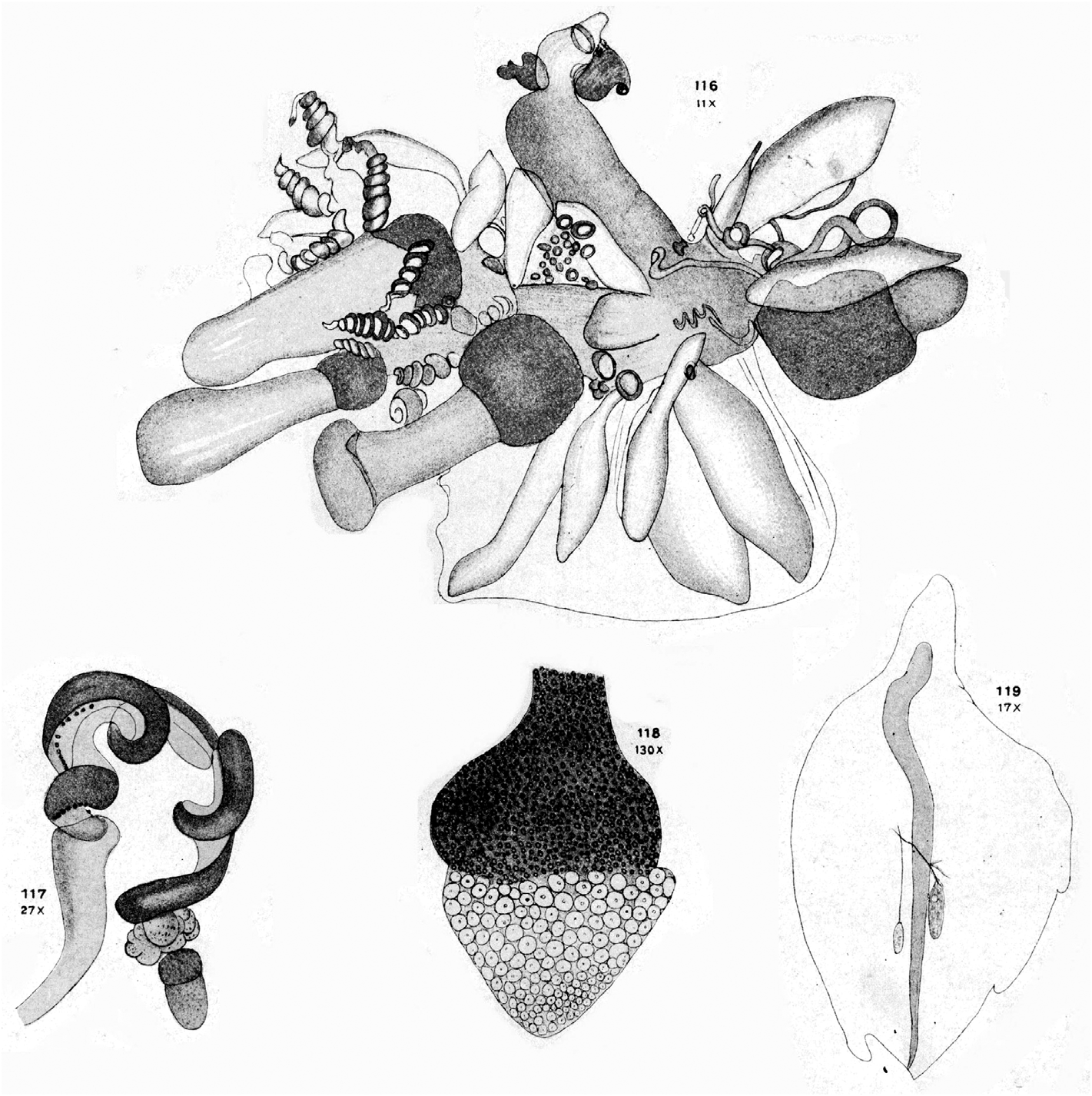

Remarks: As noted above, Lens & van Riemsdijk (1908) described a new species of Halistemma , H. cupulifera , based on a single, imperfect specimen consisting of a pneumatophore, a nectosome denuded of all mature nectophores, and a part of the siphosome with some zooids still attached (see Figure 37 View FIGURE 37 ). The size of the pneumatophore was not given, but the contracted nectosome measured 4 mm in length and 1.5 mm in diameter, and included a few buds of nectophores at its apical end. The short piece of siphosome included some fully developed female gonophores and four (+) gastrozooids, three of which were said to have tentacles with mature tentilla. The latter were described as having a cnidoband with 4–5 spiral turns, with the first two spirals containing ensiform nematocysts, but a proximal involucrum was said to be absent. The contracted terminal filament bore, at its distal end, (ibid. p. 85) "a small acorn-cup-shaped appendage ( cupulifera ) the basal part consisting of ... an agglomeration of the small circular cnidocysts of the terminal filament and proximally of many delicate ectoderm-cells". "Elongate, cylindrical, not quite transparent but more whitish opaque" (ibid. p. 86) palpons were present, which were without palpacles, but the authors correctly surmised that they had probably become detached. There were only two bracts, of which the larger was in very poor condition. The smaller was 5 mm in length and had a foliaceous appearance, with (ibid. p. 86) "two small incisions occur on both sides, which even on the right side attain the appearance of a lobe". On the upper surface there were two oval patches of ectodermal cells. They mention that microscopically small filaments arose from some of these cells, which might indicate that they were nematocysts, but they also described small canals, directed proximally, from each patch that eventually united. These must be artefacts. Although they describe two incisions on each side of the bract, their figure only shows three individual teeth. The bract most resembles our Type E bract, but because of the thickness of the canal it is almost certainly immature, which was the conclusion reached above.

Lens & van Riemsdijk's specimen was re-examined by one of us (PRP) many years ago. It seemed to have deteriorated over the years possibly because the tube it was contained in probably had once been stoppered with cotton wool, as such fibres were very prevalent. This is one of the worst things that you can do to a siphonophore specimen as the finer parts tend to become entangled in the wool and are difficult to recover. It appears that with regard to the specimen of Halistemma cupulifera no attempt was made to retrieve the entangled pieces, as there were no signs of any tentilla whatsoever with the type specimen. In addition only one mutilated bract was found, which bore no resemblance to that which they illustrated. Nonetheless there were several gastrozooids and numerous palpons, many of which possessed an obvious palpacle, so it is unclear why Lens & van Riemsdijk did not notice them. Some developing female gonophores were also present.

Thus, unfortunately, it was not possible to confirm the two most characteristic features of the specimen as described by Lens & van Riemsdijk (1908), that is the structure of the tentillum and of the bract. So we will have to rely on what the authors originally said. The acorn-like structure of the terminal process of the tentillum is, indeed, very distinctive and, although other Halistemma species have been found to have a similar structure, it is not as large as in this species. The only major difference between our material and that of Lens & van Riemsdijk is that whereas they considered that an involucrum was absent on their tentilla it is clearly present on ours (see Figure 34 View FIGURE 34 ), although barely covering the most proximal spiral of the cnidoband. However, if one looks closely at Lens & van Riemsdijk's Plate XVI, figure 117 (see Figure 37 View FIGURE 37 , bottom left), and we are grateful to one of the referees for pointing this out, there does appear to be a small flap of tissue covering the base of the cnidoband. Nonetheless, the involucrum is a very delicate structure and, as noted above, several earlier authors failed to note its presence in H. rubrum . Thus, we are satisfied that the specimens that we have described here belong to Halistemma cupulifera .

Although this is the first time that the nectophores of Halistemma cupulifera have been described under that specific name, they have probably been illustrated previously by Totton (1954, Text—fig. 16, A, B, E) as his "etype" H. rubrum . Comparisons between his illustrations (see Figure 38 View FIGURE 38 ) and our Figure 29 View FIGURE 29 will demonstrate the many similarities, for instance the sizes and relationships of the axial wings and the thrust block, and the way that the lateral ridge distinctly diverges away from the vertical lateral one, with both being joined to the apico-lateral one.

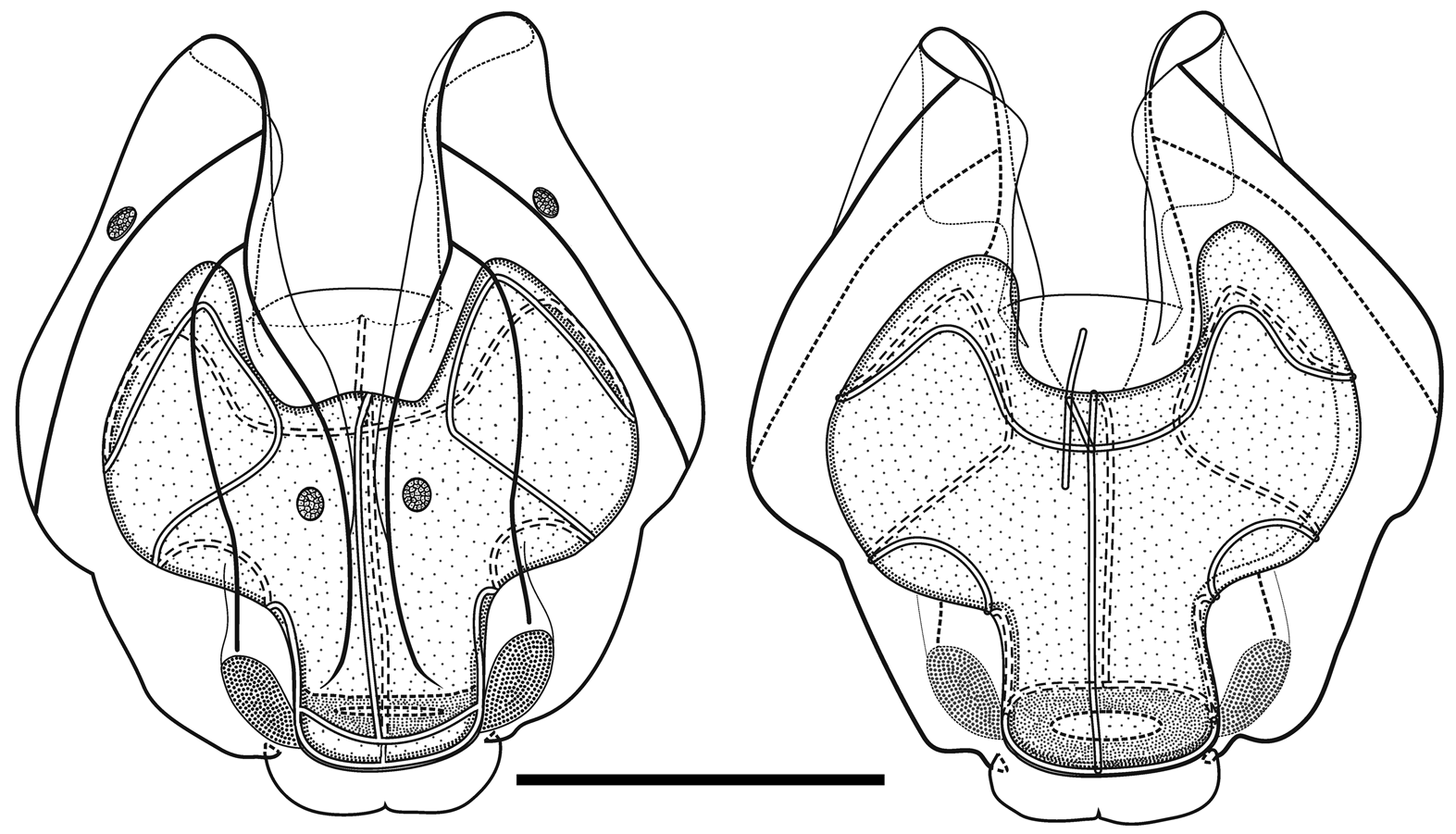

We also believe that a nectophore of this species was described and illustrated by Margulis (1976) under the name Paragalma birsteini . This species undoubtedly shows characters of the genus Halistemma , particularly with regard to the arrangement of the lateral radial canals and ridges. Although her illustrations (see Figure 10 View FIGURE 10 ) showed neither the lateral nor the vertical lateral ridges reaching the upper lateral one, while in several Halistemma species , including H. cupulifera , they both do, the general morphology of the nectophore, particularly the mouth plate, has led us to conclude that it most likely belongs to H. cupulifera , and accordingly we consider it to be a questionable junior synonym of that species.

Distribution: The type specimen of Halistemma cupulifera , from Siboga St. 244, was collected just south of the Moluccas in Indonesia. The JSL specimen came from the Gulf of Mexico, west of the Dry Tortugas, while the four other specimens examined came from the North Atlantic Ocean; one at the shelf break to the south west of Ireland, one from off Portugal, one from the mid-Atlantic at 40°N, and one from the Cape Verde Islands. In addition, another North Atlantic specimen was collected by a SCUBA diver at 20 m depth in the Sargasso Sea (24°52.13'N, 60°29.32'W) ( Pagès & Madin, 2010). Johnsen & Widder (1998) mentioned three specimens of H. cupulifera caught by a Tucker trawl in the eastern Gulf of Mexico, but the provenance of their identifications is not known.

Kawamura (1954) mentioned having caught a single specimen, which he referred to as Stephanomia cupulita off Misaki, Japan in April 1909, which had six fully-grown nectophores, and bracts 10–13 mm long and 6–8 mm wide but, apart from mentioning the distinctive terminal processes to the terminal filaments of the tentilla, that was the extent of his description. It is a pity that this was not one of Kawamura's specimens re-examined by Pagès (2002). Dhugal Lindsay (personal communication) noted that Halistemma cupulifera was present in large numbers north of Osprey Reef (off Queensland, Australia) in late July, 2012.

The "e-type" Halistemma rubrum that Totton (1954) illustrated came from Discovery St. 1585 at 0°06'S, 49°45.4'E, between Somalia and the Seychelles in the western Indian Ocean. It is not clear whether Totton's other Indian Ocean specimens of H. rubrum also belong to this species, with the exception of that from Discovery St. 1586, which belongs to the new Halistemma species described herein. The other Indian Ocean specimen that we, questionably, ascribe to this species, the Paragalma birsteini of Margulis (1976) came from Petr Lebedev St. 11 at 7°39'N, 87°54'E, which Margulis said was in the North western Indian Ocean. However, the position given is midway between Sri Lanka and the Nicobar Islands, which would be difficult to classify in the terms used by Margulis.

Alvariño et al. (1990), as referenced by Pugh (1999a), claimed to have identified specimens of H. cupulifera collected at epipelagic depths off Chile at c. 40°S, between 81 and 90°W, and between Chile and the Antarctic Peninsula. However, like all Alvariño's identifications, these must be treated with a great deal of caution, and need confirmation if the specimens still exist.

Thus, leaving apart the questionable records of Alvariño et al. (1990), Halistemma cupulifera has been collected in three very disparate regions; in the western Pacific regions of Indonesia, the Coral Sea and Japan; in the western Indian Ocean; and in the North Atlantic Ocean and the Gulf of Mexico.

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.

|

Kingdom |

|

|

Phylum |

|

|

Class |

|

|

Order |

|

|

Family |

|

|

Genus |

Halistemma cupulifera Lens & van Riemsdijk, 1908

| Pugh, P. R. & Baxter, E. J. 2014 |

Paragalma birsteini

| Margulis, R. Ya. 1976: 1244 |

Stephanomia cupulita

| Kawamura, T. 1954: 112 |

Halistemma cupulifera

| Pugh, P. R. & Youngbluth, M. J. 1988: 10 |

| Lens, A. D. & van Riemsdijk, T. 1908: 85 |