Paranadrilus descolei, Gavrilov, 1955

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/ 10.11646/zootaxa.4497.1.3 |

|

publication LSID |

lsid:zoobank.org:pub:11725C60-E463-4EB3-A96A-34CEF56923B8 |

|

DOI |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.5951344 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/5D62156B-FFD8-C842-1AEC-D1F3FAAA6812 |

|

treatment provided by |

Plazi |

|

scientific name |

Paranadrilus descolei |

| status |

|

( Figure 3 View FIGURE 3 )

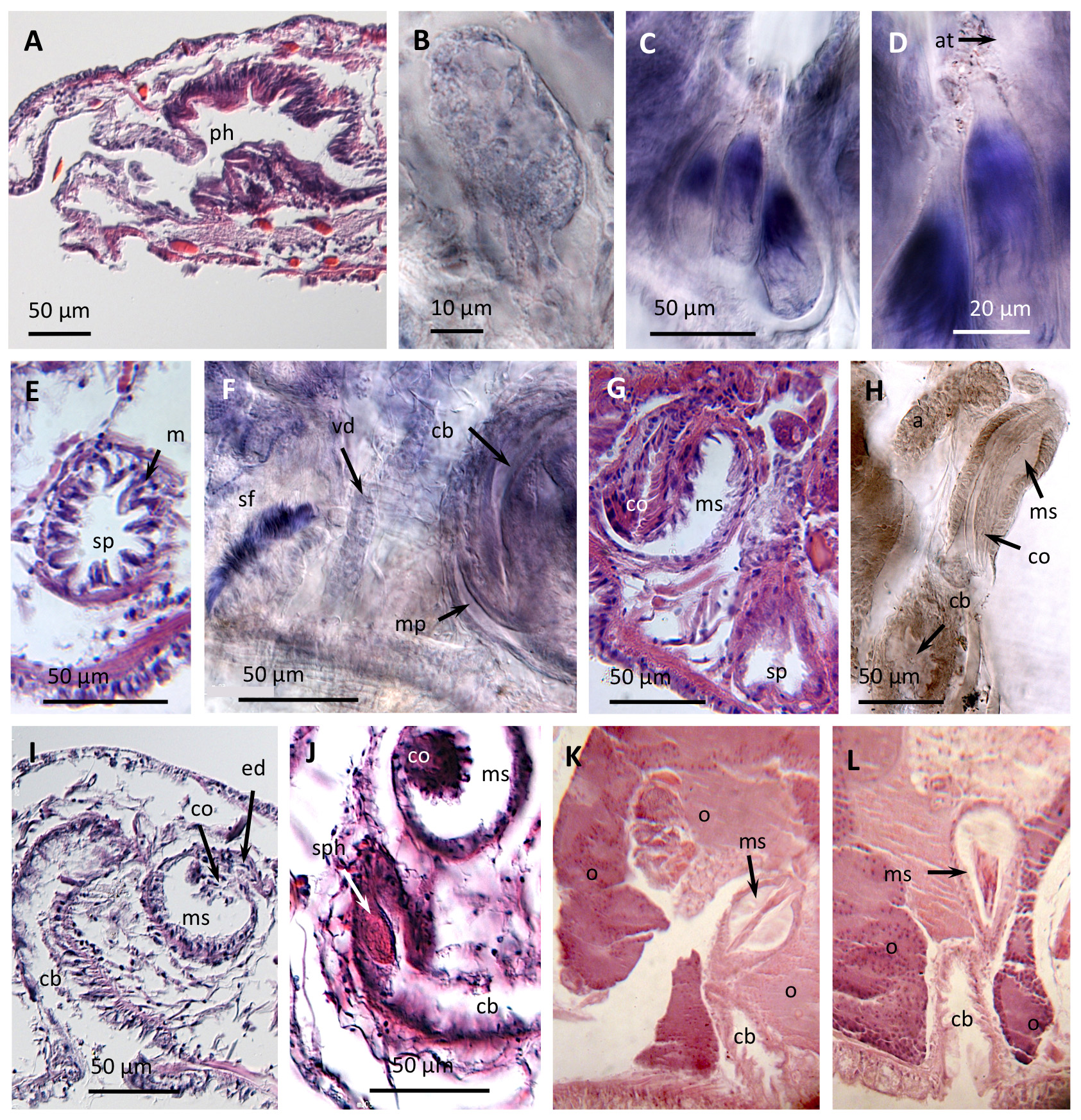

Lectotype. CH-O-FML 2349, ParVial No.13 (Series 2349-I), longitudinal histological sections (10 µm), on 2 slides. ( Fig. 3K,L View FIGURE 3 ).

A review of Gavrilov's type collection in Miguel Lillo Museum of Natural Sciences (MMLCN) by P. Rodriguez confirmed Gavrilov's (1958) description of the reproductive organs in his very detailed monograph. Gavrilov's type collection is large, composed of almost 1000 individuals from a laboratory culture, initiated with 17 field worms (4 sexually mature and 24 immature) sampled at the type locality in Las Tunas stream (Entre Ríos, Argentina) ( Gavrilov 1955a, 1958). The type collection is at the MMLCN with the reference FML 2349, and consists of syntypes (=Kotypen, Gavrilov 1955a), thus no specimen was designated as the holotype. The histological sections most probably used by the author for his drawings and the description of the reproductive system were identified, and among them, we have selected one specimen to be named lectotype.

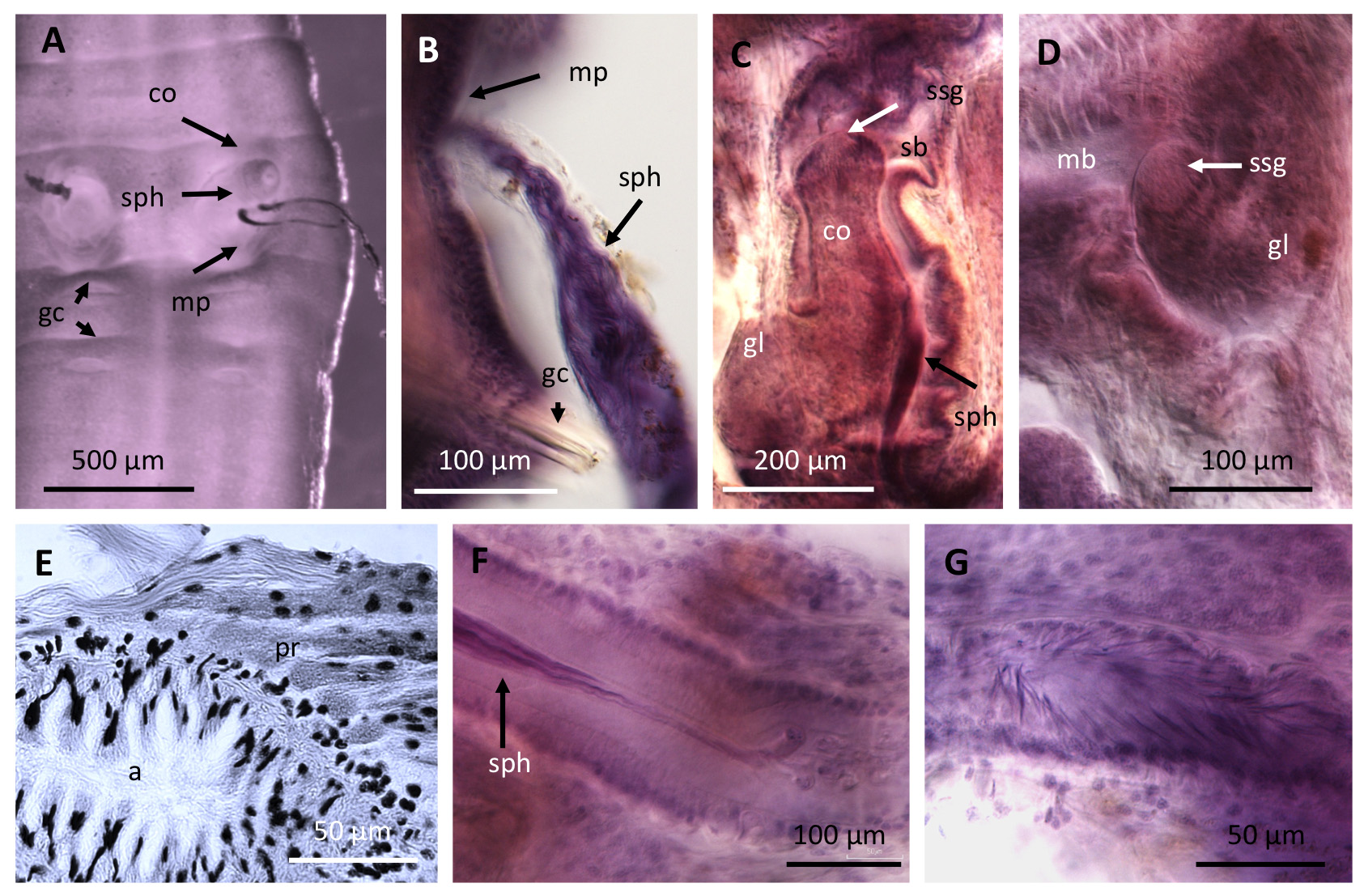

Spermathecae were absent in all mature specimens examined of Paranadrilus descolei . Spermatophores were not observed in the review of the type collection, although they were described in a few specimens in Gavrilov's monograph ( Gavrilov 1958: Fig. 5A–F View FIGURE 5 ), where spermatophores were attached individually to the body wall. In contrast, all mature specimens in Marchese's field collection had specific attachment sites for the spermatophores, within small lateral pouches not described by Gavrilov (1955a, b, 1958). Lateral pouches were never observed in the type collection. In Marchese's collection, these were latero-ventral invaginations of the body wall, containing 1 to 3 spermatophores; the narrow end of each spermatophore was apparently attached with some substance to the outer part of the pouch ( Fig. 3C,D View FIGURE 3 ). These spermatophore pouches are formed in the anterior part of segment XII ( Fig. 3G View FIGURE 3 ), with the entrance directed upwards, as described by Brinkhurst & Marchese (1987: Fig. 7). The walls of the spermatophore pouch are surrounded by musculature ( Fig. 3E View FIGURE 3 ), suggesting that as eggs pass through the female pore, the pouch would contract, and sperm from the spermatophores could easily be discharged into the cocoons to fertilize the eggs. The examined spermatophores are conical, teardrop-shaped, 68–75 µm long and 23–34 µm maximum diameter, whereas they were longer (average 93 µm) and thinner (average 16 µm width) in Gavrilov's (1958) description.

The male duct in P. descolei is composed of a small sperm funnel, placed ventrally on septum 10/11 ( Fig. 3F View FIGURE 3 ); a moderately long vas deferens; a tubular atrium, densely covered with diffuse prostatic cells; and a narrow ejaculatory duct which opens to a large male copulatory bursa [referred to as "massive penial sac" by Brinkhurst and Marchese (1987)]. This bursa is composed of an ental male sac [= bulbous ental portion of the penial sac in Gavrilov (1958)], and an ectal section presumably serving as a copulatory chamber. The ental, bulbous section has a glandular inner epithelium, and contains a pendant, copulatory organ, originally described as a penis. The copulatory organ is long and covered or not by a chinitous sheath in Gavrilov's type collection ( Fig. 3H,K,L View FIGURE 3 ); in contrast, it is short and glandular in Marchese's collection ( Fig. 3G,I,J View FIGURE 3 ). In all instances, the ectal section has a folded epithelium, and terminates in a longitudinal slit-like male pore in the ventral side of segment XI ( Fig. 3F View FIGURE 3 ). In their description of new material from other localities in Argentina and Perú, Brinkhurst & Marchese (1987) concluded that the organ described as a penis by Gavrilov was not a true penis, but rather a simple fold in the wall of the sac, not connected to the male duct. However, in both the type collection and in the Marchese's collection examined here, the glandular organ is formed in the bulbous male sac at the junction of the atrial ejaculatory duct [=efferent duct in Gavrilov (1958)] and there are no traces of the musculature expected for an intromittent organ. As Gavrilov (1955b) suggested, this copulatory organ is probably responsible for the formation of the spermatophore capsules and their attachment to the body wall of the mating partner, since in the absence of spermathecae, an intromittent organ seems unnecessary. In Paranadrilus , the material required to build the spermatophore capsule seems to be secreted within the male sac, where Gavrilov described a copious glandular secretion ( Fig. 3K,L View FIGURE 3 ). As described by Gavrilov, a chitinous sheath covering the dagger-like "penis" ( Fig. 3H View FIGURE 3 ) was observed in six specimens of the type collection, where the male duct was scarcely developed, but the ovary was voluminous and eggs were present. However, it was not observed in the lectotype, where the male duct was more developed, nor was it seen by Brinkhurst and Marchese (1987), or in the present study of Marchese's collection. The chinitous layer in the copulatory organ of Gavrilov's specimens probably represents the material ready for the spermatophore capsule, before it has been fully formed and released. Formation of spermatophores in the bulbous male sac is supported by the finding of one developing spermatophore in the most ental part of the copulatory bursa in one specimen from Marchese's collection ( Fig. 3J View FIGURE 3 ).

Only 11.2% of the individuals examined from cultures by Gavrilov (1958) had spermatophores (only 1–2 spermatophores per individual); however, in the specimens from Marchese's collection we have counted up to 6 spermatophores (3 in each ventral pouch). In Gavrilov's studies of laboratory cultures, parthenogenetic reproduction predominated; however, this can be an alteration of the reproductive biology of the species under culture conditions, and should be contrasted with field data. Gavrilov never observed the spermatophore pouches in segment XII, even though he worked with live organisms and performed histological sections. Spermatophore pouches were not seen in the present review of the type collection. This suggests that the lateral pouches were not formed under culture conditions, possibly due to a high proportion of some type of parthenogenetic reproduction [e.g. merospermy or pseudogamy, suggested by Gavrilov (1955b)]. Nevertheless, it is also possible that the genus Paranadrilus includes additional species in the Neotropical region, a question that future genetic analyses can help answer.

Although not related to spermatophore production, some organs in Marchese's collection are worth mentioning because they can be of interest in future studies of the genus: the pharynx is voluminous and dorsally folded ( Fig. 3A View FIGURE 3 ); and small (single?) mid-ventral glands are shown in the posterior part of segments IV–VII ( Fig. 3B View FIGURE 3 ).

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.

|

Kingdom |

|

|

Phylum |

|

|

Class |

|

|

Order |

|

|

SubOrder |

Rhynchobdellida |

|

Family |

|

|

SubFamily |

Haementeriinae |

|

Genus |