Trypetesa lampas (Hancock, 1849)

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/ 10.5281/zenodo.7225407 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/03AC5B7C-AF3B-3144-9D6F-F8864010F946 |

|

treatment provided by |

Valdenar |

|

scientific name |

Trypetesa lampas |

| status |

|

T. lampas position in the shell

The larger size of T. lampas specimens in the columnella part of the shell could be due to more shell material being available for burrow formation, but in general we did not detect a preference for this position. Thus, the columella may offer better option for growth but there seems to be no competition for space in the shells in our population, which also have a very low load (1.4) compared to some other studies ( Williams et al. 2011). Unlike T. maclaughlinea , T. lampas can flatten its body and may thus be less dependent on a thick layer of shell for burrow formation ( Williams and Boyko 2006).

Parasitic rhizocephalan barnacles on hermit crabs always occupy the left side of the abdomen facing the outer shell because they mimic the eggs mass and take advantage of the brood caring behaviour of their host ( HØeg and Lützen 1995). We did not record the distance of the T. lampas specimens from the shell aperture, but individuals situated far back in the shell are probably assured sufficient oxygen, because hermit crabs use their soft skinned abdomen as an accessory respiratory organ ( Vannini et al. 2004). In both male and female crabs, water circulation is assured by beating of the pleopods, which would also benefit the respiration of the symbiont reproduction in T. lampas .

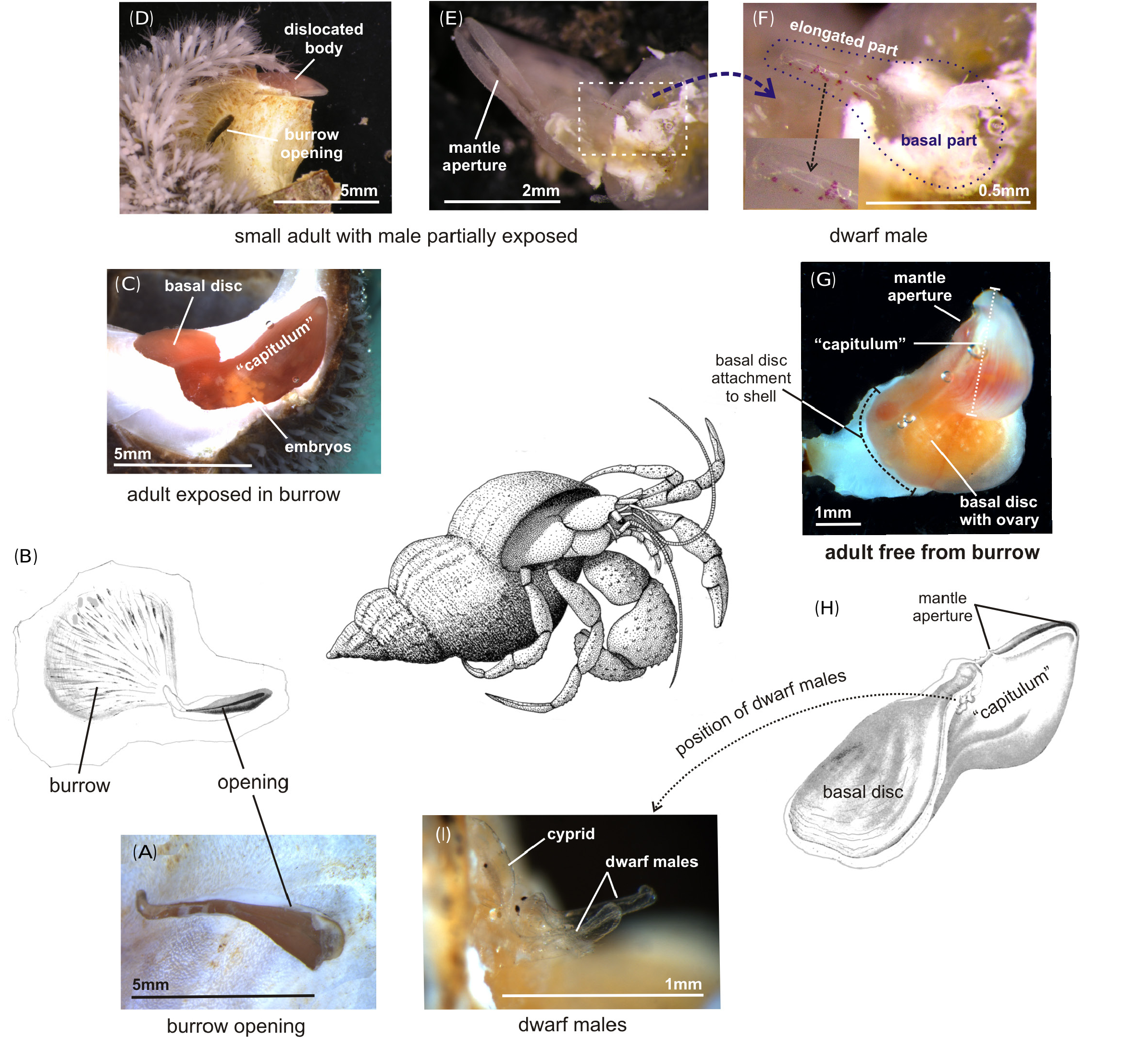

We provided evidence for a seasonal reproduction occurring in T. lampas (H6), since females was more ovigerous in the summer compared to the winter. But egg or embryocarrying females were available in good numbers in both summer and winter samples, and we even observed nauplii brooded by females in the November sample. In agreement with this, there was no seasonality in presence of the dwarf males needed for reproduction in this dioecious barnacle species. All this suggests that reproduction takes place throughout the year, at least to some extent. This is somewhat contrary to results of Kühnert (1934) from a North Sea ( Heligoland) population, but our result, based only on the ratio of egg/embryo carrying females and measured twice a year, is not an accurate estimate of total reproductive output in the population. The higher summer temperature must almost certainly decrease the time needed for brooding the larvae and also the interval between successive broods, leading to an increased output of propagules from each adult female. The presence of egg/ embryo carrying females without males may have two explanations. Firstly, some males may have been exhausted after their last sperm release and dropped away. Secondly, some of the minute and often almost transparent males ( Fig. 1 View Fig ) may well have dropped off due to the necessarily rough treatment of cracking the gastropod shell and extracting the females from their burrows.

As expected (H7) the male frequency distribution differed from random, but contrary to the hypothesis, with more females having no males than expected. This seems to indicate, together with a low mean number of males per female (0.63), that sperm competition was not important in this population.

Females with males were more likely to have eggs, either in the ovary or in the mantle cavity. This means that either the presence of males is needed for the development of eggs or females with mature eggs tend to attract males. Furthermore, the number of males was related to the female size, which means that bigger females have more males. This might have various explanations: 1) bigger females provide more space for male settlement, 2) bigger females have a higher chance of carrying eggs to fertilize and 3) bigger females have had a longer time for more males to settle. The two latter explenations seem to be the most reasonable, since males settle in a specific place on the female ( Gotelli and Spivey 1992) and therefore the settlement place should not be affected by size.

Female T. lampas almost certainly live for several years ( Kühnert 1934), while males, being unable to feed, must have a very limited life expectancy. This suggests that females must reacquire males in order to continue to be able to reproduce. Turquier (1972) reported a much higher prevalence of males in T. nassarioides (92%) than found in our T. lampas population (35.1%). At our study site a large number of females seem to be prevented from reproduction due to lack of males.

In line with our results, Kühnert (1934) also observed T. lampas males throughout the year, but especially in May to August. According to Kühnert (1934) the fertilization took place May to September and by males that settled the previous year. This may explain why we did not find any difference in male number between summer and winter.

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.

|

Kingdom |

|

|

Phylum |

|

|

Class |

|

|

Order |

|

|

Family |

|

|

Genus |

|

Kingdom |

|

|

Phylum |

|

|

Class |

|

|

Order |

|

|

Family |

|

|

Genus |

Trypetesa lampas

| Grzelak, Katarzyna & Sørensen, Martin V. 2022 |

T. nassarioides

| Turquier 1967 |