Cosmotriphora cf. melanura (C.B. Adams, 1850 )

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/10.5852/ejt.2020.665 |

|

publication LSID |

lsid:zoobank.org:pub:836C9171-0849-4F4D-BC8D-90C2D9E8B9D1 |

|

DOI |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.14370940 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/03E58799-FF91-AF5B-FE31-FE32FB73FB72 |

|

treatment provided by |

Valdenar |

|

scientific name |

Cosmotriphora cf. melanura (C.B. Adams, 1850 ) |

| status |

|

Cosmotriphora cf. melanura (C.B. Adams, 1850) View in CoL

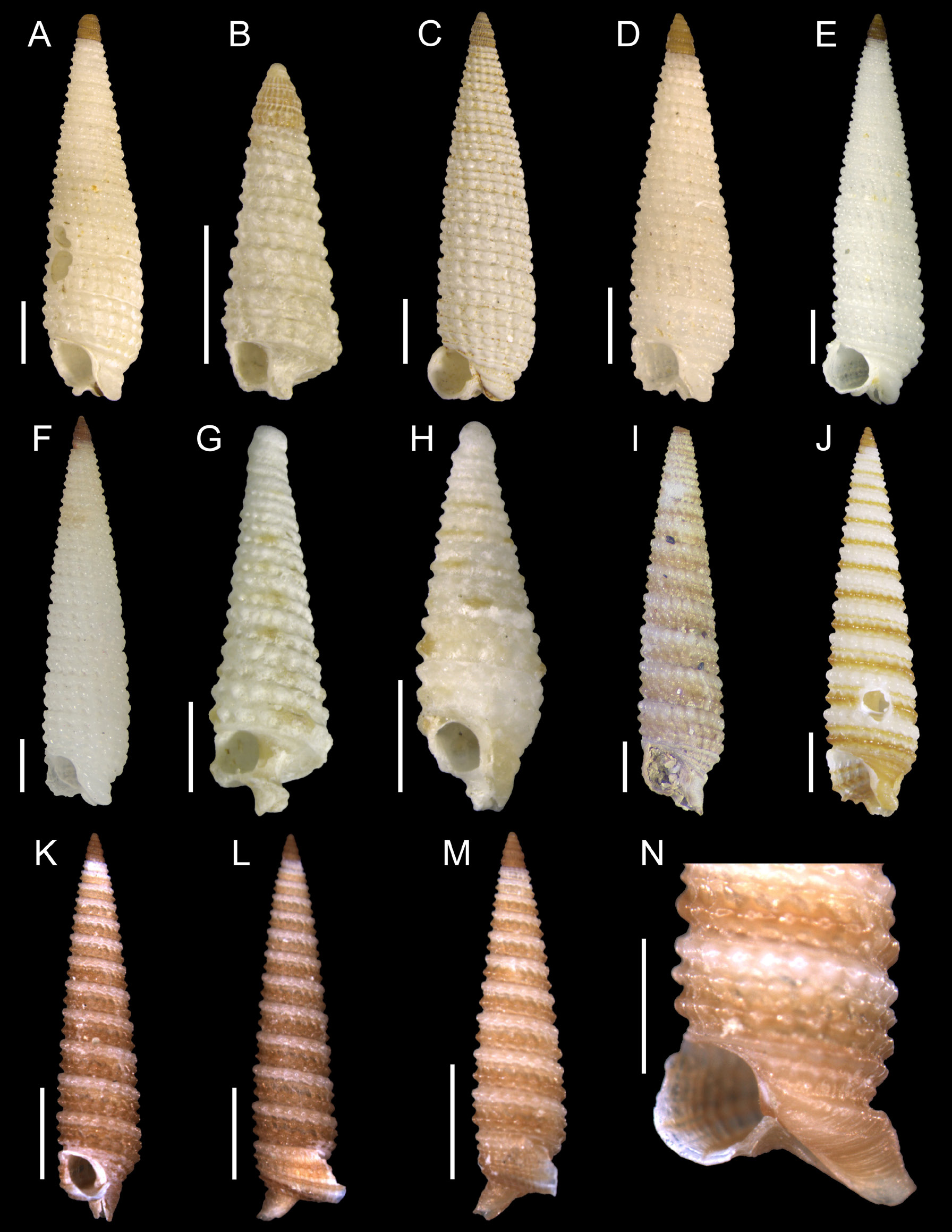

Figs 21 View Fig A–F, 32

Material examined

BAHAMAS • 1 spec.; Abaco; depth 12 m; 19 Jul. 1983; C. Redfern leg.; BMSM 55421 • 1 spec.; Abaco; depth 3 m; 12 Aug. 1981; C. Redfern leg.; BMSM 55419 • 6 specs; Abaco; depth 7 m; 13 Aug. 2005; C. Redfern leg.; BMSM 55425 • 5 specs; Abaco; depth 7 m; 12 Aug. 2007; C. Redfern leg.; BMSM 55426 .

BRAZIL – Amapá • 1spec.; Cabo Orange ; depth 103 m; Nov. 1968; MORG 14448 * • 1 spec.; 03º58′43″ N, 49º33′24″ W; 2001; MNRJ 32571 View Materials GoogleMaps * • 3 specs; off Amapá ; Apr. 1997; MORG 39890 *. – Ceará • 2 specs; Canopus Bank ; 02º14′25″ S, 38º22′50″ W; depth 60–70 m; Aug. 2005; MZSP 70279 View Materials GoogleMaps • 2 specs; Canopus Bank ; 02º14′25″ S, 38º22′50″ W; depth 60–70 m; Aug. 2005; MZSP 53736 View Materials GoogleMaps . – Rio Grande do Norte • 1 spec.; BPot MT54; MNRJ 35176 View Materials * • 1 spec.; Potiguar Basin ; MNRJ 35182 View Materials *. – São Pedro e São Paulo Archipelago • 1 spec.; Jul. 2003; G. Vianna leg.; MNRJ 32421 View Materials * • 1 spec.; Apr. 2001; P.S. Oliveira leg.; MORG 42626 • 1 spec.; 00º56′ N, 29º22′ W; 2 Nov. 2007; C.M. Cunha leg.; MZSP 87436 View Materials . – Fernando de Noronha Archipelago GoogleMaps • 21 specs; Cabeço da Sapata ; depth 40 m; 5 Dec. 1985; M. Cabeda leg.; MORG 24616 *.

Remarks

Most shells in the material herein examined are assigned, with restrictions, to Cosmotriphora melanura (C.B. Adams, 1850) owing to the late emergence of the median spiral cord in the fifth or even sixth whorl of the teleoconch, reaching the same size of other cords after about three or more whorls. A typical shell of C. melanura has the median cord emerging in the third or fourth whorl, reaching the same size of other cords after one whorl. Typical shells of C. melanura were also herein listed, being usually sympatric with the atypical ones.

Triforis grimaldii Dautzenberg & Fischer, 1906 , an eastern Atlantic species originally described from the Canary Islands and Cape Verde, is widely accepted as a synonym of C. melanura ( Bouchet 1985; Rolán & Fernández-Garcés 1994; Fernandes et al. 2013), even with its median spiral cord emerging between the sixth and eighth whorl of the teleoconch ( Rolán & Fernández-Garcés 1994). Despite the suggestion of Scheltema (1971) and Fernandes & Rolán (1994) that several species of Triphoridae can be amphi-Atlantic, only C. melanura is currently recognized as such.

In spite of the lack of knowledge about triphorid larval development, C. melanura seems to be the western Atlantic triphorid with the longest larval phase in the open ocean, being the commonest species in the seamounts and islands of the Vitória-Trindade Chain ( Fernandes et al. 2013) and in Campos Basin (southeastern Brazil) offshore waters ( Fernandes & Pimenta 2017b). The ability of larvae to cross an ocean does not imply the panoceanic presence of adults owing to difficulties of post-larval survivorship and establishment in the new territory ( Bhaud 1998), especially regarding the dietary limitations caused by the feeding mode of triphorids on particular sponges. Krug & Zimmer (2004) and Young et al. (2012) also provided arguments against the hypothesis of frequent larval exchange across the Atlantic. Several supposedly amphi-atlantic gastropods from tropical shallow waters have been proved to be constituted of different species (e.g., Malaquias & Reid 2009; Claremont et al. 2011; Carmona et al. 2014), whereas others indeed show broad ranges (e.g., Claremont et al. 2011; Padula et al. 2016).

Shells of C. cf. melanura seem to represent an intermediate phenotype with respect to the emergence of the median spiral cord between typical C. melanura and eastern Atlantic shells. The oceanic islands of Fernando de Noronha and São Pedro e São Paulo could represent a hybrid zone, being localized above a main oceanic current connecting both sides of the Atlantic (but regarding the fact that several shells of typical C. melanura are also present there). In addition, shells of C. cf. melanura are often found in the Bahamas and in deeper waters of northern and upper-northeastern Brazil (see Material examined). To elucidate whether it constitutes a complex of species or just intraspecific variation, an integrative taxonomic approach is needed. Sampling must also include oceanic islands that may serve as stepping stones for this species, like St. Helena Island ( Smith 1890).

Another hypothesis on the variation in shell morphology of C. cf. melanura proposes phenotypic plasticity owing to latent effects of the larval development ( Pechenik 2006). A common feature between atypical shells from oceanic islands and deep records is a possibly extended larval period in the water column if there is no habitat for settlement. Fernandes & Pimenta (2017b) suggested that the protoconch of C. melanura has a different color when larvae spend a long period in the water column. At least in northern and part of northeastern Brazil, it is observed that the deeper the site, the more frequent to see atypical shells, perhaps associated to latent effects and stress during an extended larval development ( Pechenik 2006). In contrast, isolated oceanic islands contain both typical and atypical shells, the former possibly derived from self-retained larvae (short larval period), the latter possibly derived from distant sources; exceptions are the ‘pseudo-isolated’ islands of Trindade and Martin Vaz, connected to the continent by the shallow seamounts of the Vitória-Trindade Chain, not showing atypical shells. Ex situ experiments with the ontogeny of C. melanura may be conducted to evaluate if delayed metamorphosis affects the development of the median spiral cord of the teleoconch. This hypothesis, however, does not explain differences in the shell between C. melanura from both sides of the Atlantic Ocean.

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.

|

Kingdom |

|

|

Phylum |

|

|

Class |

|

|

SuperFamily |

Triphoroidea |

|

Family |

|

|

SubFamily |

Triphorinae |

|

Genus |