Pseudopotamilla saxicava ( Quatrefages, 1866 )

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/ 10.11646/zootaxa.4254.2.3 |

|

publication LSID |

lsid:zoobank.org:pub:88B33DE9-BCF2-4AE4-A1B4-F0D39DCDF5C3 |

|

DOI |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6040993 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/747D7A68-FFD7-061E-FF41-F89AFC0DF34C |

|

treatment provided by |

Plazi |

|

scientific name |

Pseudopotamilla saxicava ( Quatrefages, 1866 ) |

| status |

|

Pseudopotamilla saxicava ( Quatrefages, 1866) View in CoL reinstated

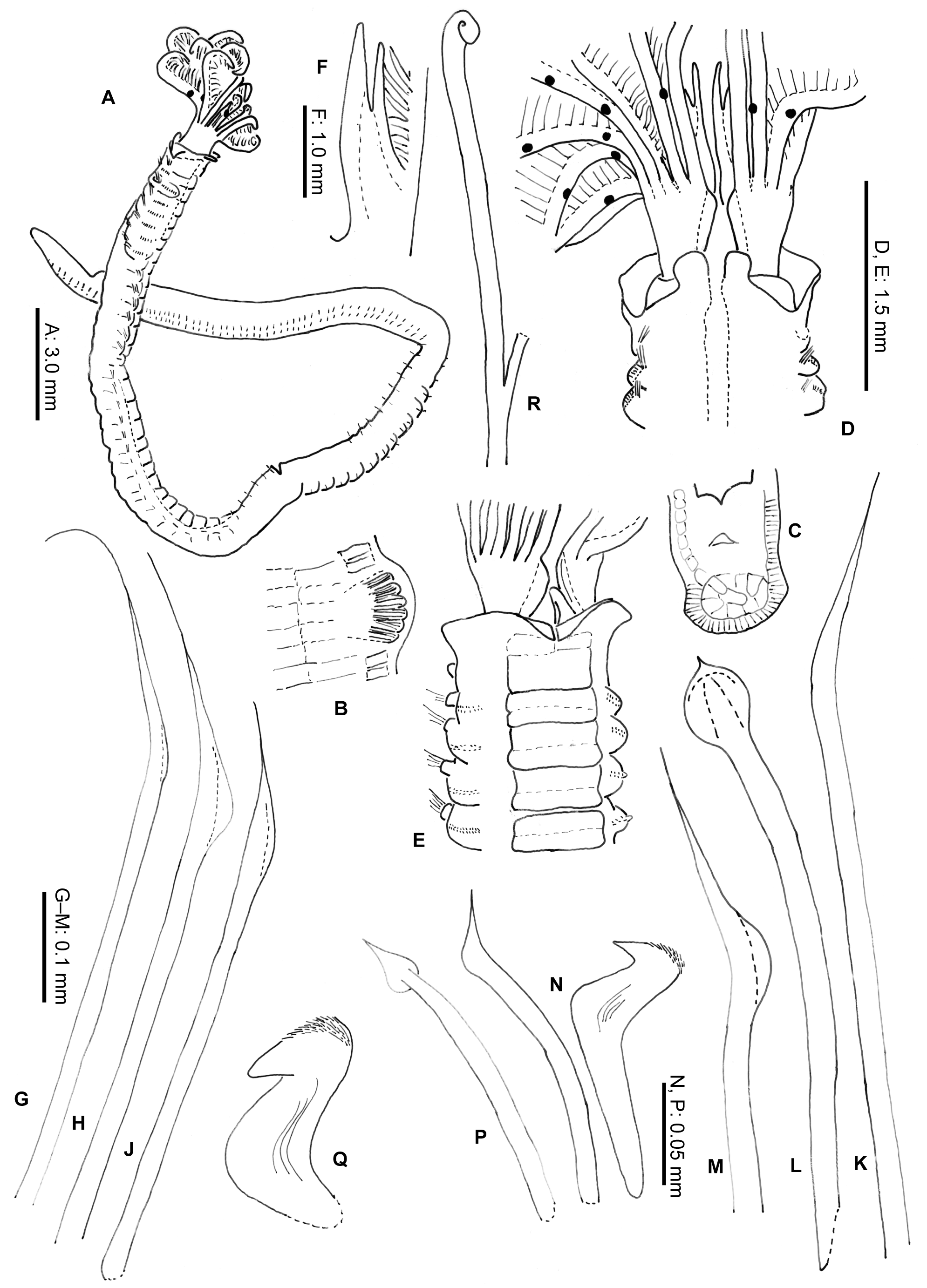

( Fig. 5 View FIGURE 5 )

Sabella saxicava Quatrefages, 1866: 437 View in CoL –438 (original material MNHN A241, A243), Guettary, southwest France.— McIntosh, 1868: 286 –287, pt. 20, figs 5–8, Plymouth and Channel Islands .

Potamilla ehlersi Gravier, 1906: 37 View in CoL –39, 1908: 87–91, pt. 6, figs 260–264, text figures 433–440 ( MNHN A246, A256), Djibouti .— Mohammad, 1971: 300 ( MNHN A480), Kuwait .— Pseudopotamilla ehlersi Ben-Eliahu, 1975: 66 View in CoL ( HUJM), Gulf of Elat.

Potamilla reniformis View in CoL .— Rioja, 1917: 64 –64, fig. 19 ( MNCM 6.01 /515), Gijon. — Rioja, 1923: 27 –29, figs 21–22, Santander, both north Spain .— Fauvel, 1927: 309 –310, fig. 107a–l, north and west France and Mediterranean.

Pseudopotamilla reniformis View in CoL .— Knight-Jones, 1981: 185, figs 13–17, 48–51, 58–60, 63; 1983: 254, fig, 3A–C; 1990: 280, fig. 6.22.— Chughtai, 1984: 46–60 fig. 3, pl. I–IV; 61–80, figs 1–3, pl. I–VIII; 81–96, fig. 2, pl. III–IV; 1986: 168, figs 9–14.— Chughtai & Knight-Jones, 1988: 231–236, figs 1, 3, 5–6, 10A (all Swansea, south-west Wales).— Knight-Jones et al. 1991: 852, Turkey (ZE).

Material examined. Type material: Guettary , southwest France, burrowing in limestone ( MNHN A241, A243, type) . Additional material: West Angle Bay, Milford Haven (south-west Wales), from low water rocks west of the northern promontory ( NMW.Z.1992.088.0007–9; NMW.Z.2009.038.0899, 0 903, 1677–1678), 1981, 1993 & 2003; West Looe, (south Cornwall, England) from northern side of low-water reef ( NMW.Z.2009.038.0902); west side of Trevone Bay , north Cornwall (KJC) ( NMW.Z.2009.038.0916).

Grube (1870) studied Quatrefages’ (1866) original material of Sabella saxicava commenting on their “not quite satisfactory preservation”. As much work has been done on southwest Wales material ( Knight-Jones 1981, 1983, 1990; Chughtai 1984, 1986; Chughtai & Knight-Jones 1988) this description is based on one specimen of many ( NMW.Z.2009.038.0903) from West Angle. Data in brackets refers to Chughtai 1984 (C), Quatrefages 1866 (Q), Grube 1870 (G).

Diagnosis. Collar with low, rounded lappets dorsally; dorsal collar margin convex; peristomium not exposed above collar margins; lateral margins of collar even (in line with the horizontal body axis); handle of companion chaeta slightly longer than handle of adjacent uncinus.

Description. Body without radiolar crown about 33 mm long, 1 mm wide. Crown 2.3 mm long ( Fig. 5 View FIGURE 5 A) with nine (G 7, Q 6) pairs of radioles, ventral-most radioles shortest, lacking eyes, with one to two single compound eyes ( Fig. 5 View FIGURE 5 B), R x21 xxxxxx, L xx11xxxxx (C 1–4, Q 1–3, G 1–5). Interradiolar web absent. Bases of crown about 5 mm long. Dorsal margins with narrow flanges parallel to each other ( Fig. 5 View FIGURE 5 C), ventral margins with oblique flanges accommodating ventral sacs ( Fig. 5 View FIGURE 5 D). Large dorsal lips nearly half length of radioles, each with bifid appearance ( Quatrefages 1866, “les antennes 4”) being supported by radiolar appendage (mid-rib) and an enlarged pinnule at base of the adjacent radiole. Paired dorsal collar lappets, low, extending a little above junction of crown and thorax, with lower parts fused to sides of midline faecal groove ( Fig. 5 View FIGURE 5 C) and lateral margins more or less parallel to axis of body joining with slightly oblique lateral collar margins lower (without distinct V-shaped notch, Fig. 5 View FIGURE 5 B). Ventral collar with highest part (when not relaxed) close to midline cleft in front of two ventral sacs ( Fig. 5 View FIGURE 5 D). Thorax with 10–12 (Q 12, G 12) segments, abdomen with up to 200 (Q 60) segments. First thoracic segment not much longer than following ones (viewed laterally, Fig. 5 View FIGURE 5 B). Anterior margins of first ventral shield indented medially. Following ventral thoracic shields rectangular, each with indistinct transverse groove (grooves separating shields well defined). Thoracic tori with a wide gap between ventral ends and lateral margins of shields ( Fig. 5 View FIGURE 5 D). First thoracic fascicle with fairly short, slightly hooded chaetae, hood a little wider than handle. Similar superior chaetae in other thoracic fascicles (about 4), but longer above hood ( Fig. 5 View FIGURE 5 F). Inferior chaetae (about 8) paleate with a small distal mucro ( Fig. 5 View FIGURE 5 G). Abdominal chaetae of one kind: elongate, broadly hooded with curved handle just below hood, hood nearly twice width of handle ( Fig. 5 View FIGURE 5 J). Thoracic uncini (about 5) each with numerous crest teeth covering half of main fang, distance between end of handle and breast twice as long as between breast and crest ( Fig. 5 View FIGURE 5 H, right). Companion chaetae with similar length handles to those of uncini ( Fig. 5 View FIGURE 5 H, left) and with flat tear-drop distal blades ( Knight-Jones 1981: Figs 58–60 SEM as P. reniformis ). Abdominal uncini smaller than those of thorax and with shorter handle ( Fig. 5 View FIGURE 5 J). Tube thin, dried mucous within burrow and thicker distally with layer of muco-silt and detritus.

Colour. Fixed specimens with crown pale with yellow and opaque white bands, radiolar eyes dark orange-red; body ochre yellow, but ventral shields whitish.

Remarks. Although Grube (1870) looked at material of Sabella saxicava in the MNHN, he still regarded the species to be a junior synonym of “nierenformige Amphitrite ” ( Pseudopotamilla reniformis ), but he noted that the material was in “not quite satisfactory preservation”. In spite of McIntosh’s (1868) careful studies of Sabella saxicava in southwest England, he too subsequently (1923) synonymised the species (and P. aspersa ) with P. reniformis . Rioja’s, 1923, fig. 21 (north Spain) is more like Malmgren’s (1867) fig. 77A of P. reniformis from Greenland than that of Pseudopotamilla saxicava . Fauvel (1927, Fig. 107b) seems to have copied that figure, but his figure 107a seems to be original and is typical of P. saxicava .

All three new species of Iroso (1921, as Potamilla ) from the Gulf of Naples were synonymised with P. reniformis by Hartman (1959). As P. saxicava has been found to the west and the east of Italy and as Potamilla tronculata Iroso had their tubes within an empty oyster shell and P. oligophthalma Iroso was within Porites or valves of molluscs, it seems more likely that at least these two ‘species’ should be referred to P. saxicava . Iroso says nothing about the habitat of Potamilla obscura except that it never forms colonies. She mistakenly separated the three species on numbers of radiolar eyes and the length or absence of the mucro on each spoon-shaped thoracic chaeta.

Compound eyes are variable in number in P. saxicava (up to five per radiole) and the mucro, which arises from the leading ‘edge’ of each paleate chaeta, can be angled between 45° and 90° to the handle ( Knight-Jones 1981, fig. 49), in which case it would only be seen if the chaeta is observed in side view. When such chaetae are mounted under the pressure of a cover slip, they mostly take up a ‘front view’ and the mucro may not then be seen. She comments (under P. tronculata ) that Gravier’s text figure (1908: 435) of a spatulate chaeta terminates in a long slender point (mucro), whereas that of P. tronculata is truncated! Iroso’s watercolours of the worms (1921: pl. 3, figs 5–7) are elegant, but they do not show details of thoracic collars. The Gravier figure (1908: 260) of dorsal collar lappets of Pseudopotamilla ehlersi are more narrow distally than material from Swansea, but those from Elat (NBE, KJC) showed more variation and were typically more broadly rounded distally and with fairly straight lateral margins.

Pseudopotamilla polyophthalmus Hartmann-Schröder, 1965 (Homonym, ZMUH P–15243, Chile) seems to be a junior synonym. The gross morphology seems to be identical with that of P. saxicava View in CoL , but chaetal comparisons are still to be completed.

Pseudopotamilla saxicava View in CoL differs from both P. reniformis View in CoL and P. aspersa View in CoL in being a species with prominent ventral collar lappets (relative to crown base) and without posteriorly-pointing dorso-lateral collar notches. When compared with just P. aspersa View in CoL , the handles of the thoracic uncini are relatively longer and those of the companion chaetae are relatively shorter.

Habitat. Pseudopotamilla saxicava is reported to be a boring species. At Bracelet Bay, Swansea the emergent parts of the muco-silt tubes, with enrolled distal aperture like that of Pseudopotamilla reniformis ( Fig. 1 View FIGURE 1 R), indicated the presence of Pseudopotamilla in unusually hard limestone. Such pieces of rock, removed with a hammer and chisel, showed galleries with some containing P. saxicava ( Chughtai 1984 as P. reniformis ). The species seemed to have taken advantage of the shelter of cavities at the bases of old Hiatella (piddock) excavations, where the distal parts had been eroded by sea abrasion. The sabellid bores into the hard limestone by chemical means ( Chughtai & Knight-Jones 1988, Fig. 1 View FIGURE 1 ). To record oocyte size, collections were made every month except March ( Chughtai 1984, table II, as P. reniformis ) and no asexual reproduction was observed. Broadcast spawning was, therefore, assumed ( Chughtai 1986). The absence of boring sabellids at the same site in 2003 was curious as other fauna was much the same. The only observable difference was that Hiatella borings into the limestone were much more numerous, leaving little room for sabellid borers. At West Angle, where the rock seems to be less hard, the population of P. saxicava was as abundant as it was in the 1980’s. At Hannafore, West Looe (Cornwall), specimens of P. saxicava were harder to find in 2003 than in the 1980’s, but they were numerous in a small area on one low-water reef. The rock here has very fine laminations, so P. saxicava has less boring to do and the specimens were much easier to remove after chiselling with the grain.

McIntosh, 1868 (as Sabella ) refers to a record from Plymouth in which P. saxicava (as Sabella ) was found in limestone. He had also frequently found the species boring into oyster, Pecten , Anomia , and other dead and living shells dredged off the Channel Islands. In the Gouliot caves on the island of Sark (Channel Islands), he found the species amongst barnacles encrusting the cave walls with their tubes standing proud, having pierced the barnacle shells and coiled themselves in grooves (presumably of their own making) between the barnacle and rock. Pseudopotamilla saxicava can also be found emerging from encrusting bryozoans, sponges and ascidians. Gravier (1908, as Potamilla ehlersi ) found it within the calcareous structures of Porites, Fauvel (1927 as P. reniformis) within old shells and Ben-Eliahu (1975, as Pseudopotamilla ehlersi ) within Dendropoma .

Other material, which seems to be P. saxicava , has been found in galleries in crud (‘ Lithothamnium ’ and shell) in the Bay of Islands, New Zealand, boring through old oyster shells on a rope at the University of Hawaii Marine Station on Coconut Island, off Oahu, and in dead coral at the mouth of Pearl Harbour, Hawaii (KJC). These all have the typical collar and the enrolling of the tube mouth of P. saxicava , but more ventro-lateral radioles also bear compound eyes, except for material from Pearl Harbour.

Material identified as P. reniformis , (MEP, ZMUC POL 849) from holding tanks at the Marine Fisheries laboratory, Milford, Connecticut (originally from a Long Island oyster farm) were found boring in oyster shells. The collar is like that of P. saxicava , but their tubes do not enrol distally, so the ventro-lateral radioles are not truncated and more ventral radioles bear eyes; radioles can bear up to six eyes, but one to three is more common. Thus one should consider Pseudopotamilla oculifera ( Leidy, 1855, as Sabella ) from Rhode Island, but that form enrols its distal tube, to judge from Leidy’s figure 55 where the radioles are differentially truncated on one (always the ventral) side. This and its habitat indicates that Leidy’s species is P. reniformis (see above) and the habitat of the Long Island material would suggest P. saxicava , except that the distal tube does not enrol distally. More detailed studies of habitat, and the shape of the thoracic collar may be necessary to confirm that the Long Island material is really P. reniformis and the Rhode Island specimens are P. saxicava .

Distribution. Pseudopotamilla saxicava has a wide distribution in temperate and tropical waters. It is found in Britain, France, Spain, Adriatic, Gulf of Elat, Red Sea and Arabian Gulf.

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.

|

Kingdom |

|

|

Phylum |

|

|

Class |

|

|

Order |

|

|

Family |

|

|

Genus |

Pseudopotamilla saxicava ( Quatrefages, 1866 )

| Knight-Jones, Phyllis, Darbyshire, Teresa, Petersen, Mary E. & Tovar-Hernández, María Ana 2017 |

Potamilla reniformis

| Fauvel 1927: 309 |

| Rioja 1923: 27 |

| Rioja 1917: 64 |

Potamilla ehlersi

| Ben-Eliahu 1975: 66 |

| Mohammad 1971: 300 |

| Gravier 1906: 37 |

Sabella saxicava

| McIntosh 1868: 286 |

| Quatrefages 1866: 437 |