Chthonerpeton noctinectes

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/ 10.5281/zenodo.156280 |

|

DOI |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.5618012 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/D85C87E0-FFE7-5E35-FEF7-BA6C53DDFC2C |

|

treatment provided by |

Plazi |

|

scientific name |

Chthonerpeton noctinectes |

| status |

|

Chthonerpeton noctinectes spn. nov.

Holotype:— MNRJ 10581, an adult male collected at Sítio (11º 50' S, 37º 35' W, at sea level), Municipality of Conde, State of Bahia, Brazil, by Hélio Ricardo da Silva, Mônica Cox de Britto Pereira, and Hussam Zaher in February, 1989.

Paratypes:—Ten adult females ( MNRJ 10583590, 10592193) and two adult males ( MNRJ 10582, 10591) collected with the Holotype.

Diagnosis:—A species of the Chthonerpeton indistinctum group characterized by (1) 94–103 primary annuli, (2) 100–108 vertebrae, (3) 26–36 premaxillarymaxillary teeth, (4) 20–33 vomeropalatine teeth, (5) 23–28 dentary teeth, and (6) marked sexual dimorphism in the width of the vent area (males being larger).

The number of primary annuli and vertebrae distinguishes Chthonerpeton noctinectes from C. indistinctum (72–79 annuli and 82–86 vertebrae). C. noctinectes is distinct from C. braestrupi and C. exile in having the tentacle closer to the naris than to the eye ( Table 1 View TABLE 1 ). C. noctinectes may be promptly distinguished from C. arii on the basis of color; C. arii has a dark gray dorsum, light gray flanks, and a distinctive longitudinal yellow stripe midventrally. The smaller number of premaxillarymaxilary, vomeropalatine, and dentary teeth distinguishes C. noctinectes from C. perissodus .

Description of holotype:— Morphometric and meristic data are presented in Table 1 View TABLE 1 . The specimen is an adult male with slits in both sides of the jaw, which were made in order to facilitate the observation of characters inside the mouth. Also, as a result of the fixation process, the body shape, which was cylindrical in life, became somewhat ventrally flattened.

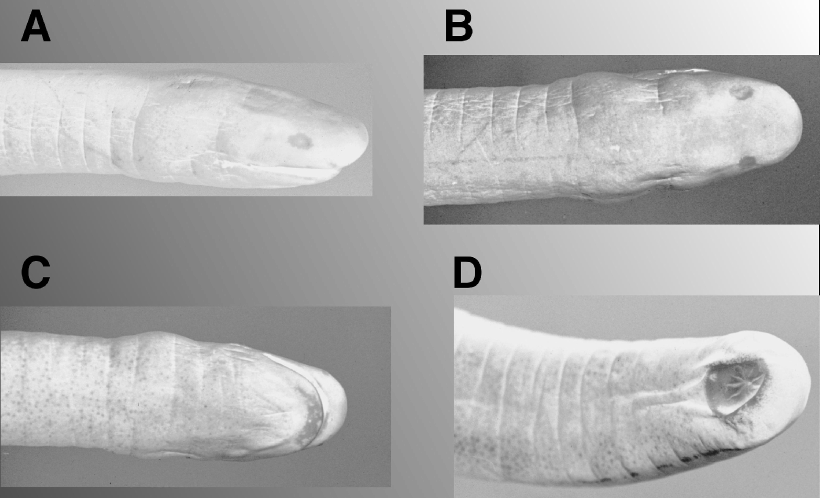

Head oval in dorsal view, larger in the nuchal region, blunt anteriorly. Eyes dorsolaterally oriented, covered by a white and opaque epidermis ( Fig. 2 View FIGURE 2 A, B); lens minute but easily discernible. Tentacular apertures minute, visible in anterior, lateral, and ventral views; encircled by an oval, white epidermis ( Fig. 2 View FIGURE 2 A), closer to nares than to eyes and below eyenaris line. Naris minute, oval, and anterolaterally oriented. Mouth recessed, snout projecting 2.7 mm in front of it. Teeth small, monocuspid, pointed, and recurved. Choanae close to each other, circular (1 mm in diameter), with choanal valves relatively shallow and easily observable. Tongue with two unpigmented narial plugs, its posteriormost portion with a sagital groove.

Two nuchal collars are clearly visible ventrally and laterally; first thicker than the second ( Fig. 2 View FIGURE 2 C), bearing two incomplete grooves ventrally and three incomplete ones dorsally. Ninetynine primary annuli; body robust, ratio of total length to width at the midbody 24.6: 1 mm. Scales absent. Body terminus rounded, forming an unsegmented shield 7.5 mm long. Cloacal disk circular; situated in a depression surrounded by a skin fold ( Fig. 2 View FIGURE 2 D), and divided into twelve cloacal denticulations, the two lateral ones each bearing a small anal papilla. One hundred and six vertebrae.

Coloration: Dorsally the body is a uniform dark bluishgray, covered by minute white spots. The cloacal disk is white. The anterior margin of the lower jaw bears an irregular crescent white area. The coloration pattern has not changed after fixation.

Variation: Measurement data for the holotype and paratypes are presented in Table 1 View TABLE 1 . Tooth counts are presented in Table 2 View TABLE 2 . The general color pattern of the series of paratypes agrees with the description presented for the holotype. Paratypes differ from the holotype in having a larger and more irregular white ventral area at the midbody, and a larger white area around the vent. A whitish eye eyetentacle stripe also varies among the paratypes. Three states occur: a) stripe is absent, as in the holotype; b) stripe is incomplete, beginning around the tentacle aperture and not reaching the eye; and c) stripe is complete going from the eye to the tentacle (in this case it is narrow and tenuous).

The cloacal disk also shows variation in the number and in size of denticulations ( Table 1 View TABLE 1 ). Some individuals present all denticulations about the same size, and in others the size varies, with some of the denticulations being half the size of the larger ones. Some denticulations also show incomplete subdivision.

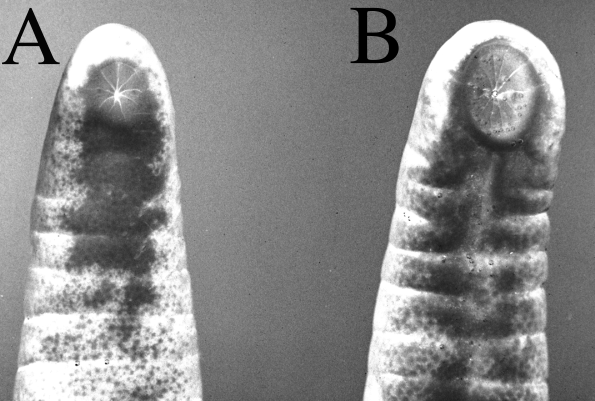

Disk papillae (= anal glands of Taylor, 1968) are not exclusive to males. They can also be found in some females ( Fig. 3 View FIGURE 3 A), although they are smaller than those of males. There is an obvious sexual dimorphism in the shape and width of the body terminus, with males being larger than females ( Fig. 3 View FIGURE 3 A, B). The body width around the vent area proved to be an adequate measurement in distinguishing males from females. A Student's ttest showed that this area in males are significantly larger then that of females (t = 4.9, P> 0.95). This expression of sexual dimorphism in the vent area is different from that presented in C. indistinctum in which only the cloacal disk is smaller in females ( Barrio, 1969 and Gudynas and Williams, 1986).

One male specimen, MNRJ 10692, collected with the type series, has measurements, vertebrae and primary annuli counts within the range for the type series, but is otherwise unusual. Although not smaller (270 mm) than the type specimens it is markedly thinner, with the smallest body width measurement for the entire sample (BW = 7.0 mm), differing by 2.8 mm from the next smallest specimen (MN 10589, BW = 9.8 mm). It also has a higher tooth count for all teeth series (ranges for paratypes in parentheses): PM= 50 (26– 36); VP = 40 (23–33) D = 33 (23–28); S = 10 (4–8). This specimen also differs from the rest of the type series in the shape of its head, which is clearly blunter and not oval, having its largest width at the middle of the head, not at the nuchal region. Because of these differences we chose not to include this specimen in the type series. Although it falls within the range of variation reported for C. perissodus ( Nussbaum and Wilkinson, 1987) , we prefer to regard the specimen as an aberrant C. noctinectes rather than a C. perrisodus because they just appeared in one specimen and the type locality for C. perissodus is about 1.500 km away, and we have only a single such specimen

Etymology:—The specific name is an adjective derived from nocti (Latin [nox, noctis] nocturnal) and nectes (Greek [nekton, nektos] swimmer), as an allusion to the nocturnal swimming activity of the species.

Habitat:—The specimens were collected in a large marsh, fed by the Itapicurú River, almost 10 km from the river month. The marsh resembles a big lake, and is basically composed of two distinct environments. One is a flooded terrain (used for cattle grazing during the dry season), and the other is an area submerged almost all year round. Aquatic plants were found covering almost all the surface of the marsh.

Several individuals were seen at night by the shore of the marsh actively swimming or coming up the surface to breathe. During the day no individuals were observed. Although at night many of them were seen, only a few could be collected due to their agility as swimmers and the slipperiness of their bodies. Other specimens were collected buried about one meter deep into a mud bank about a kilometer from the river canal.

Biology:—Four individuals, two females (MNRJ 1059293) and two males (MNRJ 1059091), all collected with the type series, were kept in captivity for some months. They were all kept together in a large aquarium and also showed nocturnal habits, swimming actively at night. During the day they remained coiled among the plants ( Fig. 3 View FIGURE 3 ) or among themselves. They showed subaquatic fossorial habits, burying themselves into the gravel without coming up to breath for hours.

The captive individuals received a diet of chicken meat and living tadpoles of Phasmahyla guttata (Hylidae) . As soon as the chicken meat was offered, they actively searched for the food, but it always took them almost a minute to find and take it. They appeared clumsy when confronted with this food. Somehow it was not easy for them to locate static food at the bottom of the aquarium. Sometimes they bit the gravel or another individual nearby, or even moved away from the food. When tadpoles were offered, their behavior was quite different. They also became more active as the tadpoles were placed in the aquarium, but they were able to find them much more easily. Almost invariably they attacked and ate the tadpoles with one precise strike. These observations suggest that this species of Chthonerpeton is able to perceive prey chemically and by movement. It may be possible that they are able to sense vibrations in the water and use them to locate food; the sense of smell also seems to be of importance.

One of the captive females (MNRJ 10593) was probably pregnant when collected in February of 1989, and at the beginning of April of the same year gave birth to eight young. At first, three young were born, then two, and three more within an interval of two days for each group. The newborns all resembled the adults, and have no external gills or any observable external larval characters. They also ate chicken meat, and were observed eating the sloughed skin. Sloughing was often observed in both the young and the adults.

After some time in the aquarium, many individuals were observed with red nematodes coming out of their mouth and cloaca. Within a few days after we had detected the presence of the nematodes, the behavior of the infected individuals began to change. They moved slowly and remained near the surface until death. We believed that the infestation of nematodes, identified as being of the Genus Camallanus , was the cause of their death.

Remarks:— Nussbaum (1986) used the position of the choanal valves, together with other characters, in justifying the division of the genus Chthonerpeton into two subgroups. According to him, the valves in the genus could be either recessed (the C. viviparum group) or superficial (the C. indistinctum group). Our examinations of the material of Chthonerpeton available to us did not reveal any differences in the relative position of the valves in C. indistinctum , C. viviparum , or C. noctinectes . The valves in the specimens we examined were all near the surface and easy to observe.

TABLE 1. — Measurements and meristic data for the type series of Chthonerpeton noctinectes.

| Males | Females | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Holotype | Paratypes (2) | Paratypes (10) | |

| TL | 334 | 286–318 | 254–345 |

| BW | 14.00 | 12.00–14.90 | 7.00–13.70 |

| HL | 10.60 | 8.60–10.60 | 3.62–9.80 |

| HW | 10.40 | 8.20–10.00 | 7.00–10.00 |

| IOD | 6.00 | 5.30–6.10 | 4.30–6.00 |

| IND | 4.00 | 3.60–3.70 | 2.70–4.10 |

| END | 4.80 | 3.80–5.50 | 3.00–5.00 |

| ETD | 3.50 | 3.00–3.40 | 2.10–3.90 |

| TND | 2.00 | 1.90–2.00 | 1.30–2.00 |

| CD | 12 | 10–11 | 9–12 |

| EMD | 2.20 | 1.75–1.80 | 1.50–2.30 |

| TMD | 1.30 | 1.00–1.15 | 0.70–1.45 |

| NV | 106 | 101–105 | 99–108 |

| PA | 99 | 95–101 | 94–103 |

| PW | 7.10 | 6.30–8.70 | 4.20–7.10 |

TABLE 2. — Tooth counts for the Holotype and selected Paratypes of Chthonerpeton noctinectes.

| MNRJ 10581 | MNRJ 10584 | MNRJ 10587 | MNRJ 10591 | MNRJ 10592 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tooth Series | Holotype | Paratype | Paratype | Paratype | Paratype |

| PM | 30 | 39 | 26 | 26 | 31 |

| VP | 30 | 25 | 23 | 29 | 27 |

| D | 25 | 27 | 25 | 23 | 22 |

| S | 5 | 8 | 4 | 4 | 4 |

| MNRJ |

Museu Nacional/Universidade Federal de Rio de Janeiro |

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.