Etyus martini Mantell, 1844

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/ 10.5281/zenodo.5397969 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/C5482F17-9033-FFD4-C7EE-F99CFF6FFACE |

|

treatment provided by |

Marcus |

|

scientific name |

Etyus martini Mantell, 1844 |

| status |

|

Etyus martini Mantell, 1844 View in CoL

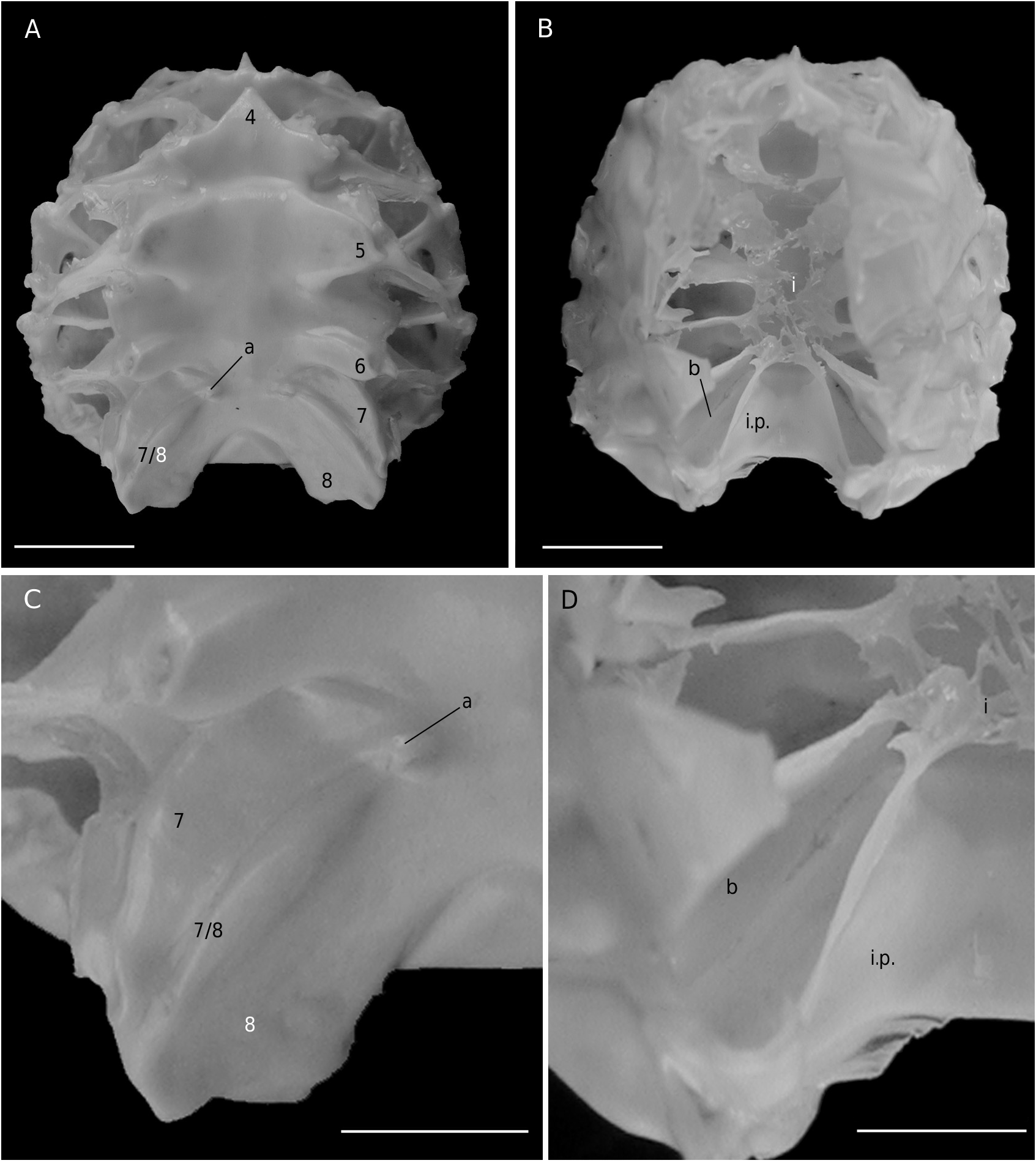

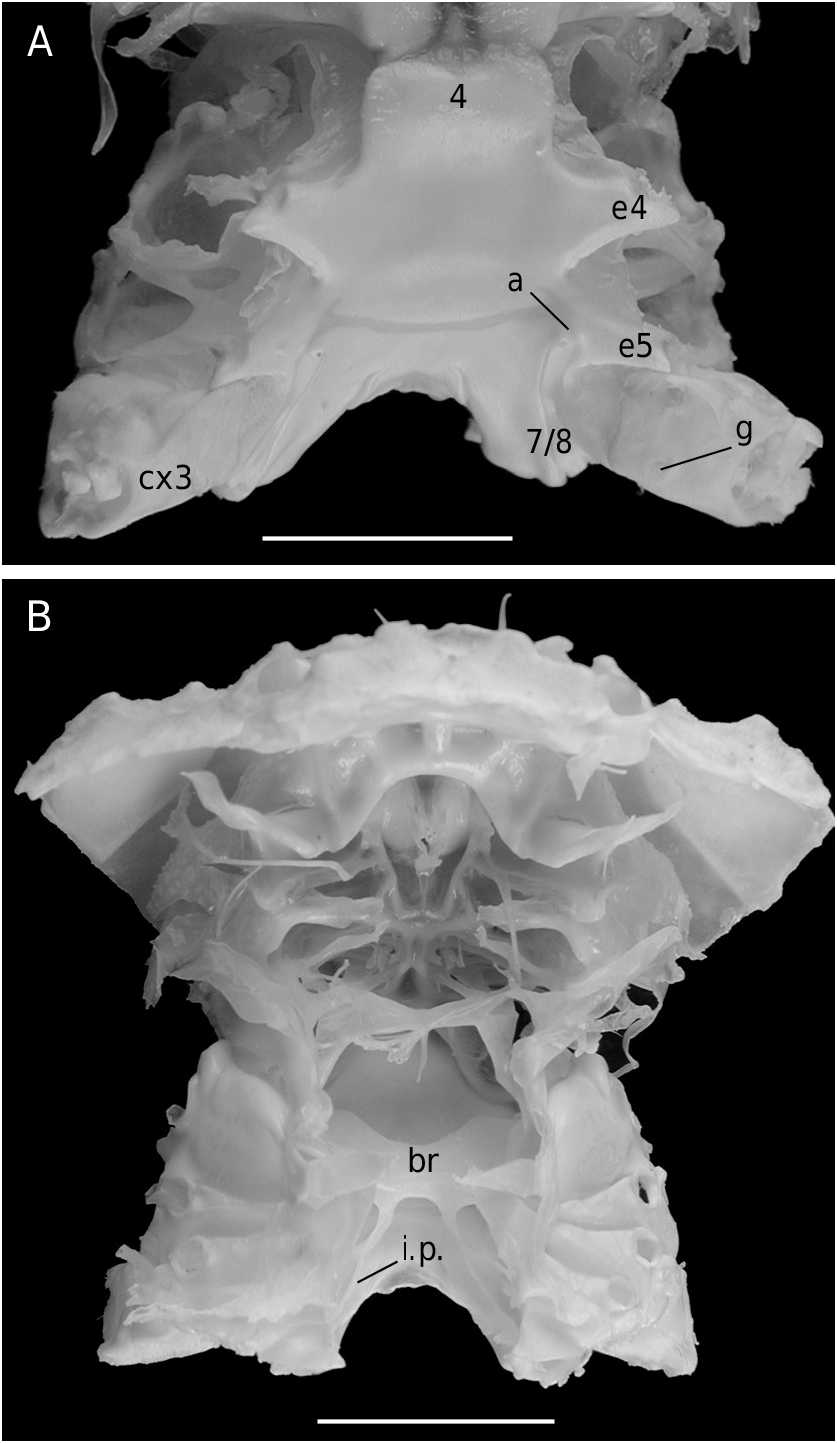

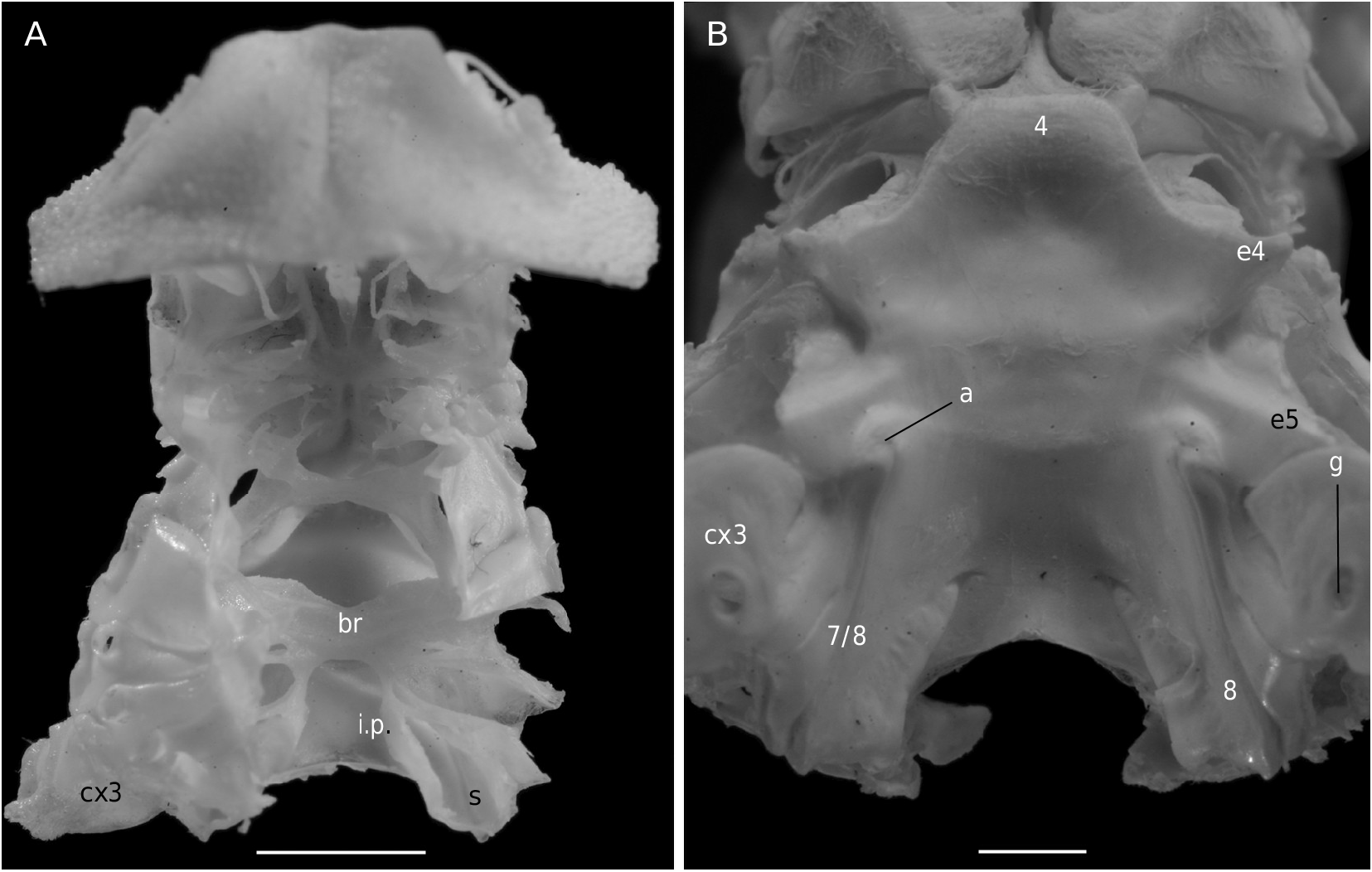

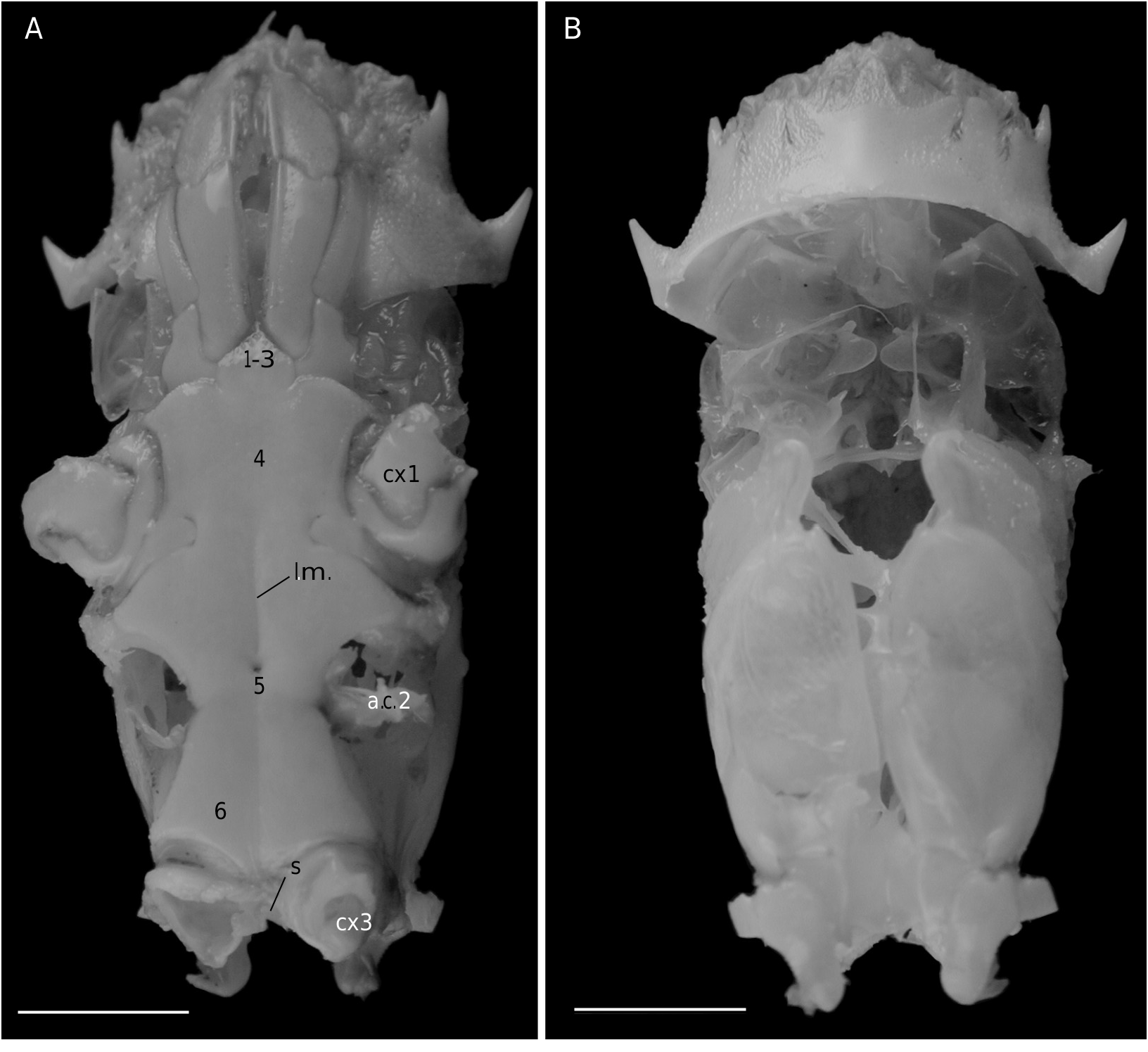

In Etyus martini View in CoL , from the European Cretaceous, two oblique and relatively large slits at the extremities of the sutures 7/8 ( Wright & Collins 1972: 102, pl. 21, fig. 6d, e) were considered homologous to spermathecal apertures by Guinot & Tavares (2003: figs 2, 3, 10J).

THE AXIAL SKELETON

IN THE PODOTREME GROUPS

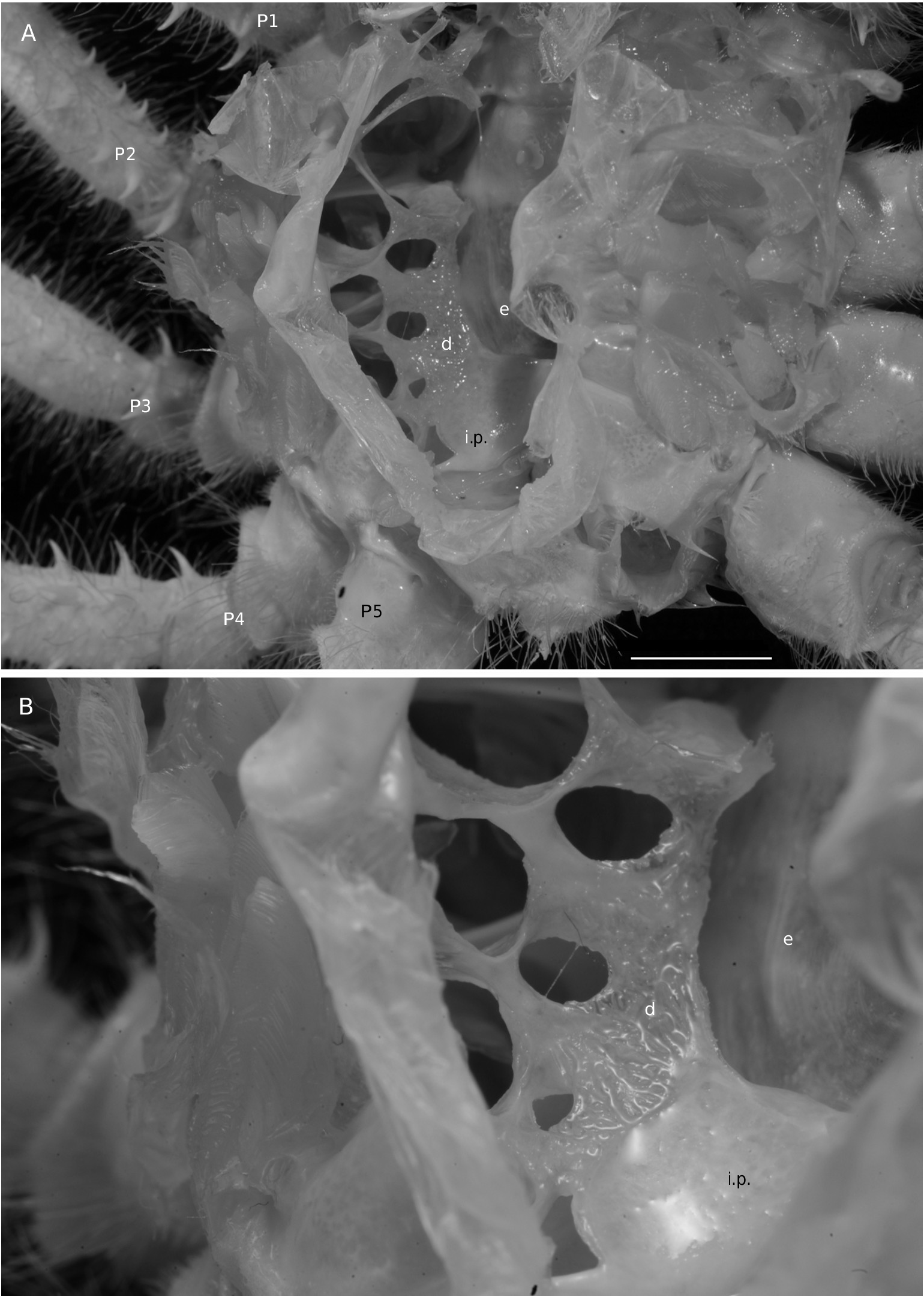

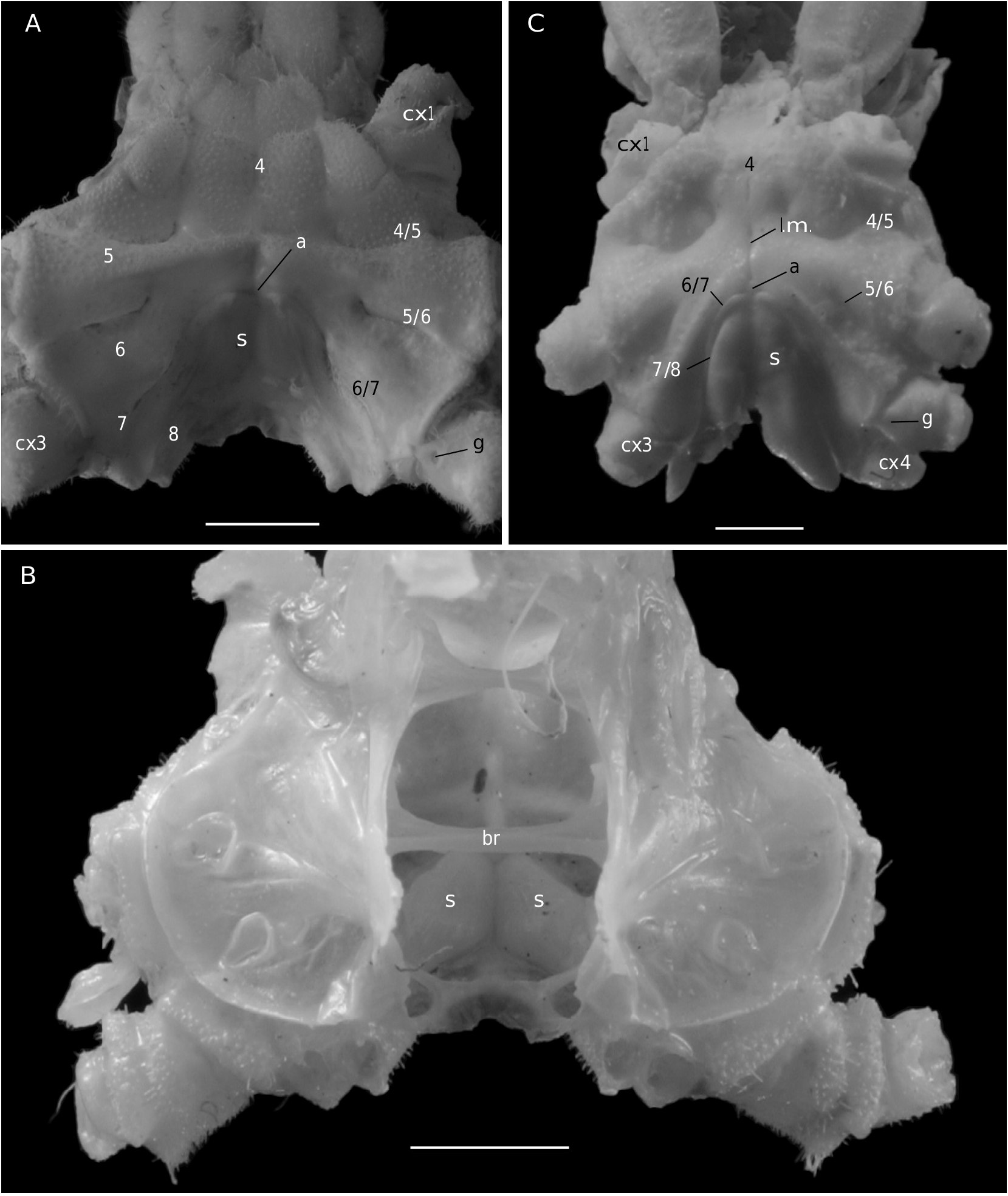

The axial skeleton is a relatively poorly studied structure. The condition of the spermatheca, directly linked with the axial skeletal organization, specially in its posterior part, and always initially lying within endosternite 7/8, provides some interesting information. In the Brachyura phragmal organization proves to be consistent with the phylogeny, showing different evolutionary stages ( Drach 1950, 1959, 1971; Secretan 1983, 1998). The different patterns are briefly presented herein.

The Homolodromiidae ( Fig. 3B, D View FIG ) shows a regularly layered, partitioned skeleton, and a binding of the endopleurites effecting transversally in the median axis, metamere by metamere, with several median connections by interfingering. This certainly represents the most primitive organization of the Recent crabs. Short endopleurites join together longitudinally, but the last endopleurite, which is shorter, has no contact with other phragmae, while the large intertagmal phragma extends towards the last endosternite and joins it ( Secretan 1998: 1758, figs 12, 13).

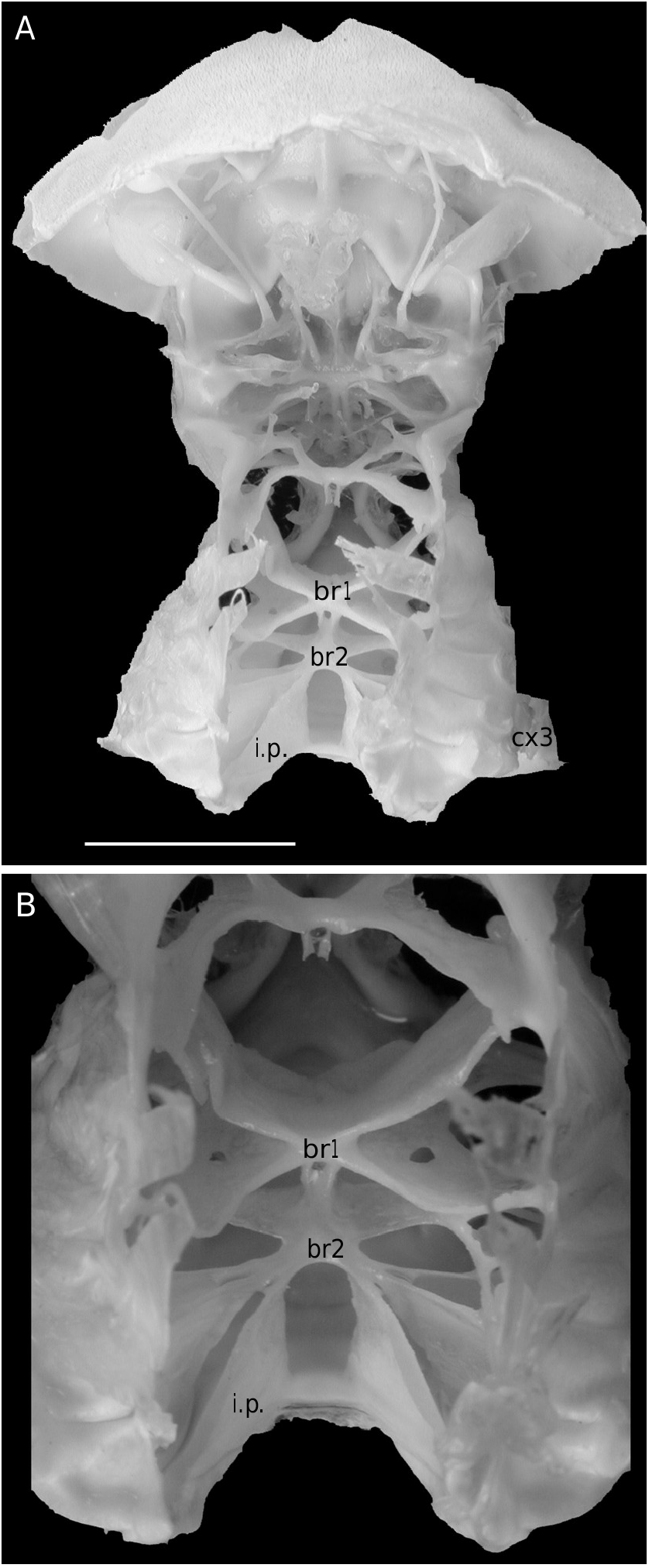

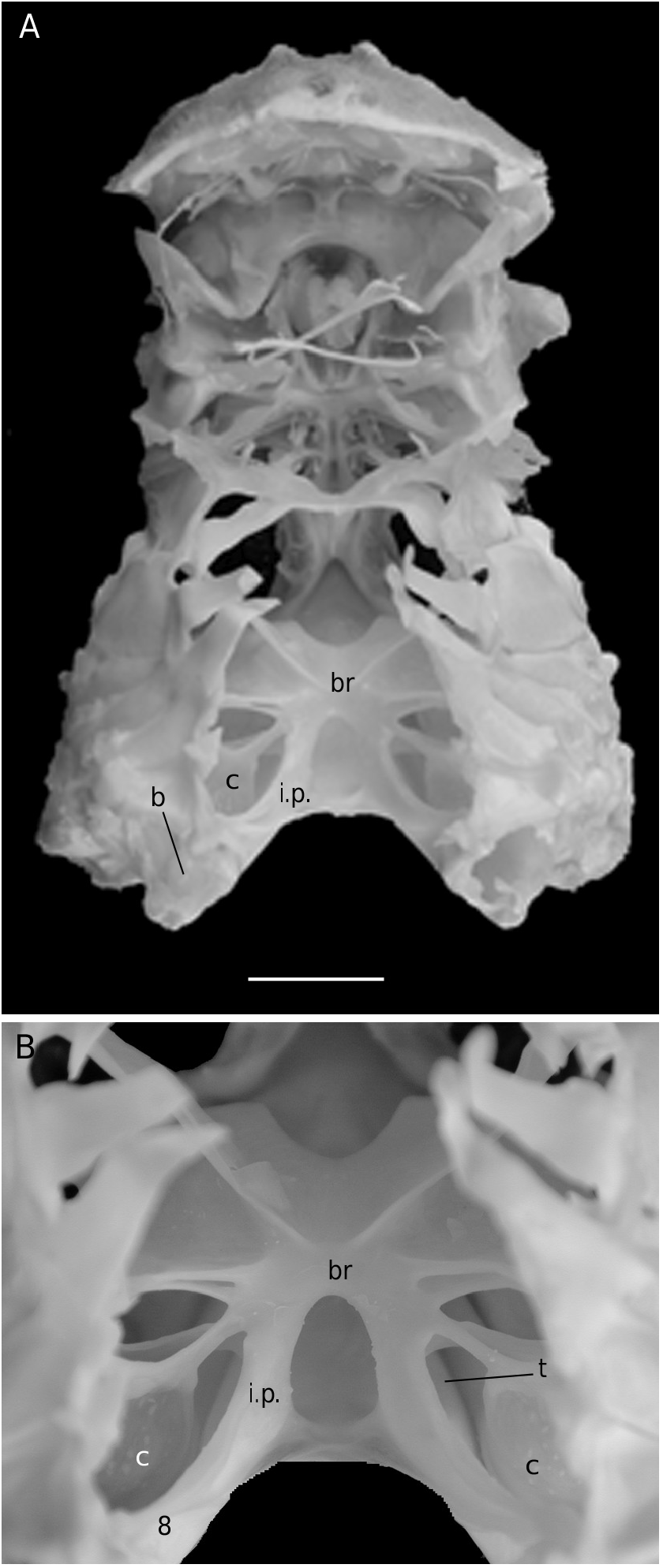

The pattern in Dromiidae and the Dynomenidae markedly differs from that of the Homolodromiidae . Endopleurites of each lateral part join together longitudinally and remain on the sides; the two sides are connected by wide transverse connections constituted by the grouped endosternites. The connections occur by fusion, such as in the advanced Brachyura . The intertagmal phragma extends and fuses with endosternal part of the skeleton. There is no sella turcica ( Drach 1971: 290; Secretan 1998: 1758, figs 7-11).

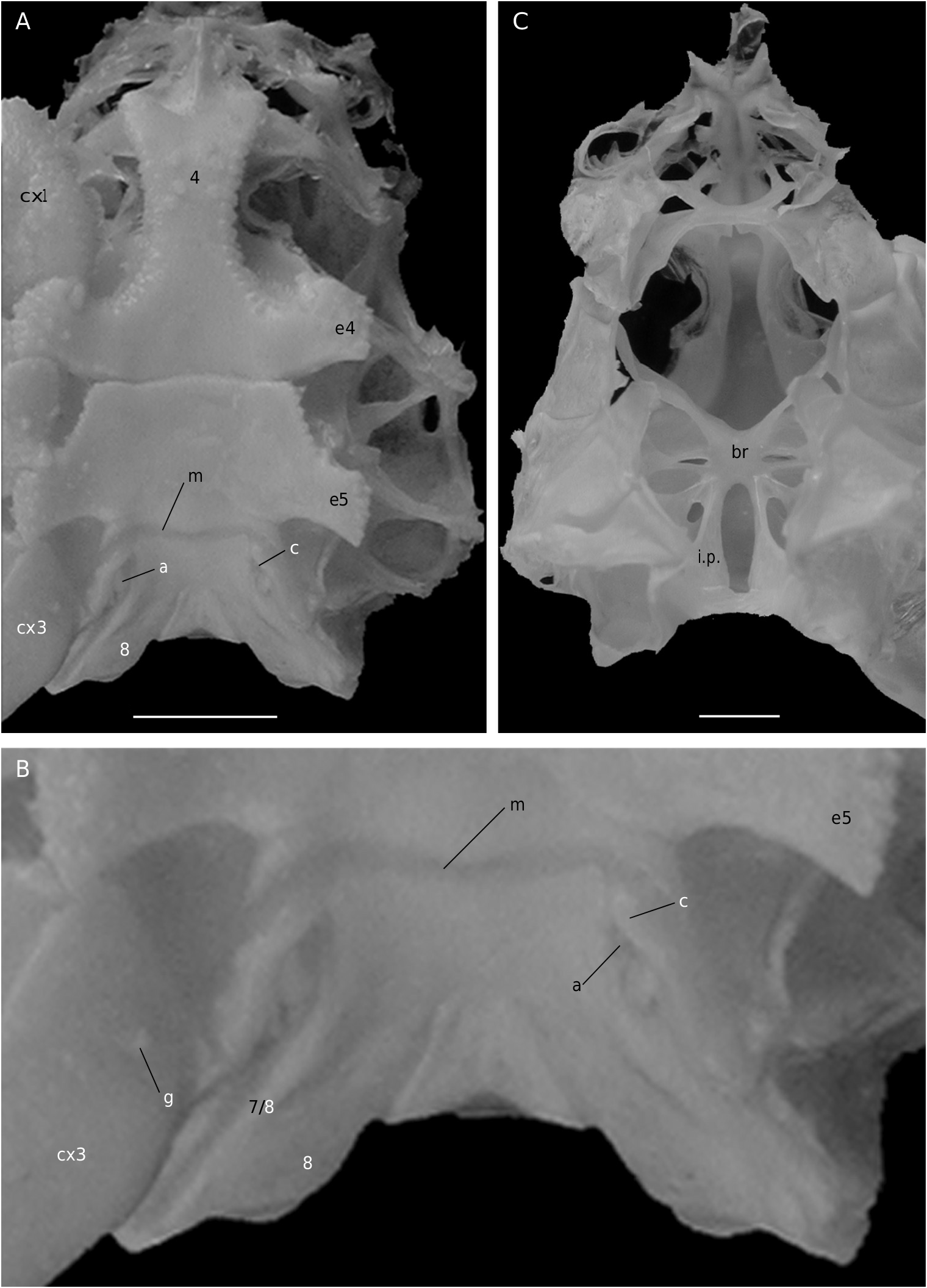

For the first time the axial skeleton in the Sphaerodromiinae ( Fig. 17 View FIG ) and the Hypoconchinae ( Fig. 16C View FIG ) is observed and described herein. Dissections have shown a layered skeletal organization and the presence of two transverse bridges in the Sphaerodromiinae (considered the plesiomorphic condition), in contrast to a more complete median concentration and only one transverse bridge in the Dynomenidae ( Fig. 4B, D View FIG ), Hypoconchinae ( Fig. 16C View FIG ) and Dromiinae ( Figs 7 View FIG ; 10B View FIG ; 11A View FIG ; 12B View FIG ) (apomorphic condition). The Dromiinae , which has elaborated a long, calcified spermathecal tube in the females and have modified uropods in dorsal plates that allow the holding of the abdomen in males, now proves to be markedly specialized crabs. In the dynomenid axial skeleton, at least three distinct patterns (probably four, when the primitive Acanthodromia A. Milne-Edwards, 1880 is dissected) are present, with the following polarity: Paradynomene (probably plesiomorphic condition), Metadynomene ( Fig. 4B View FIG ), Dynomene ( Fig. 4D View FIG ), that corroborates the more advanced condition of Dynomene already pointed out ( Guinot & Bouchard 1998). The Dynomenidae , known since the Jurassic, was perhaps confused with the Sphaerodromiinae in fossil record, because they share similar carapace outline, shape of fronto-orbital region, antennules and antennae.

In certain respects the Homolidea, with a less marked convergence of skeletal parts and junction by interdigitation (interfingering) ( Fig. 18 View FIG ), retains a more ancestral condition of the axial skeleton than the Dromiidae . Nevertheless, in contrast to Nephrops norvegicus (Linnaeus, 1758) (see Secretan-Rey 2002), the pleurites are in an oblique position (vertical in Nephrops ) and the endopleurites do not reach the median axis (versus stretching out toward median axis in Nephrops ). In the numerous homoloid genera that were examined, the intertagmal phragma lengthens toward the median endosternites-bridge, to which it joins partially without any contact with the endopleurites. The Homolidea, which exhibits a skeletal pattern somewhat intermediate between the astacidean and eubrachyuran patterns ( Secretan 1983: fig. 1; 1998: fig. 16), forms a lineage different from that of the Dromiacea. The spermathecal chamber is relatively simple and directly opens to the exterior, there are no specialized uropods, and abdominal maintaining is made by using the coxae of pereopods but adding the “homoloid” press button. The Homolidea is, with the Homolodromiidae , the most ancient podotreme group, known since the Jurassic ( Wehner 1988; Müller et al. 2000).

In the family Poupiniidae , Poupinia hirsuta shows a peculiar skeletal disposition ( Fig. 22 View FIG ), with a general organization similar to the homolid one, but there is no median junction, and digitations (which form the median binding in the other Homolidea) completely cover dorsally the endopleurites. An analogous case of laterally shifted digitations is observed in the “carcinized” anomuran crab Lomis hirta (Lamarck, 1818) ( Lomisidae Bouvier, 1895 ), where the median axis is devoid of a central bridge, the digitations are only at the extremities of the endopleurites and also partly covering them. The taxonomic placement of Lomis is controversial ( Tudge 1997; McLaughlin & Lemaitre 1997; see discussion in Martin & Davis 2001: 48). Further studies about this peculiar skeletal pattern found (homoplasically) in the Poupiniidae and in the Lomisidae may help in the interpretation about their questioned basal or advanced position in their respective groups, Brachyura Homolidea and Anomura. To our knowledge, the Homolodromioidea and the Homolidea are the only cases in the Brachyura where phragmae, instead of connections by fusion, join by interfingering ( Secretan 1998: figs 12, 13). It does not mean a close relationship, however, only a plesiomorphic condition.

The axial skeleton was not known in the Cyclodorippoidea . In the two cyclodorippids that were examined in this study, Tymolus (Cyclodorippinae) ( Fig. 23B View FIG ) and Krangalangia (Xeinostomatinae) , the narrow transverse bridge shows connections by fusion, there is a strict lateral location of the endopleurites, and the intertagmal phragma is reduced.

The skeletal organization of the Raninoidea ( Fig. 26B View FIG ), which is strongly modified, with distortion and particularly extreme dorsal flexion of the rear part but showing distinct patterns in the different subfamilies, constitutes a separate investigation by itself, one that is out of the scope of the present one.

Thus, the podotreme crabs show different evolutionary stages of their median connections and in the fusion of their intertagmal phragma with other skeletal parts. Some Podotremata ( Homolodromiidae, Homolidea ) show the same kind of connections by interfingering as the other Decapoda (such as Nephrops norvegicus ), instead of connections by fusion ( Dynomenidae , Dromiidae, Cyclodorippoidea, Raninoidea ) as the Eubrachyura. In the Eubrachyura the intertagmal phragma has become the sella turcica for it is always fused to both endosternal and endopleural phragmae, the median binding(s) has(ve) disappeared and the phragmal structures have been separated into two lateral parts ( Secretan 2002). In the primitive Eubrachyura these lateral parts are close to the median axis (narrow thoracic sternum with sutures 4/5 to 7/8 parallel and continuous), and in the advanced ones (wider thoracic sternum with sutures 4/5 to 7/8 variously interrupted) the phragmae are widely separated and isolated on each side. Another structure, the junction plate (fused to sella turcica) transversally connects the lateral phragmae, reinforces the skeletal system and ensures its cohesion. These different steps may be considered “transformations” and “progression” (terms used by Secretan 1998) from a primitive ground plan to reach the carcinized condition by means of fusion, new junctions and compartmentation. This “progression” does not involve a phylogenetic conclusion, but the general skeletal scheme permits to consider a podotreme group combined with the eubrachyuran one.

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.

|

Kingdom |

|

|

Phylum |

|

|

Class |

|

|

Order |

|

|

Family |

|

|

Genus |

Etyus martini Mantell, 1844

| Guinot, Danièle & Quenette, Gwenaël 2005 |

Etyus martini

| Mantell 1844 |