Iridotriton hechti, Evans & Lally & Chure & Elder & Maisano, 2005

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/ 10.1111/j.1096-3642.2005.00159.x |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/EB23879D-B04E-E967-FE9D-FED7FAC715D7 |

|

treatment provided by |

Diego |

|

scientific name |

Iridotriton hechti |

| status |

sp. nov. |

IRIDOTRITON HECHTI SP. NOV.

Derivation of specific name: in honour of the late Max Hecht, one of the first authors to describe salamander material from the Morrison Formation.

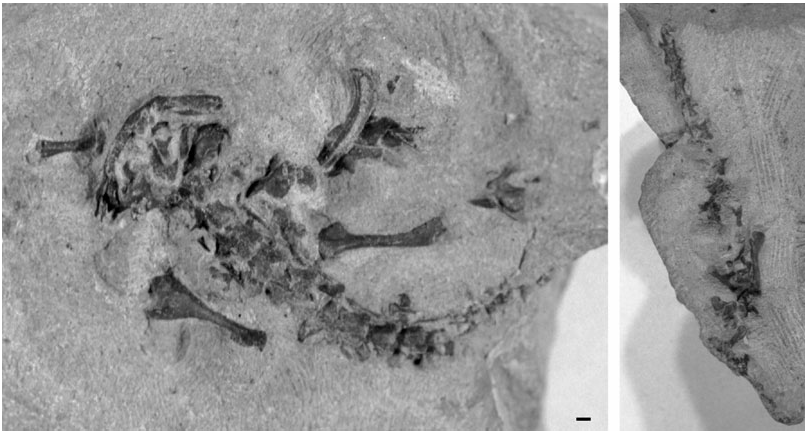

Holotype: DINO 16453 View Materials a, b, parts of a single skeleton missing only small skull bones, digits and the distal tail.

Locality: Dinosaur National Monument, Rainbow Park microsite (Dinosaur National Monument no. 96), Utah, USA (detailed locality data is held in the records at the Monument).

Horizon: Brushy Basin Member of the Morrison Formation, Upper Jurassic (c. 150–148 Myr; Kowallis et al., 1998: Kimmeridgian or early Tithonian).

Specific diagnosis: a small (snout- sacrum length c. 55 mm) fully metamorphosed salamander distinguished by the following combination of characters: thin unsculptured skull bones; a fully open Meckelian fossa in the dentary; premaxilla with wide, short alary process having angled lateral edge; prootic, opisthotic and exoccipital form a single unit, although sutural lines separate the opisthotic from the other bones; stapes free; parasphenoid without internal carotid foramina, narrower anteriorly than posteriorly; an estimated 16 postatlantal presacral vertebrae; simple ectochordal vertebral centra, with small anterior basapophyses but no ventromedian keel; atlas shorter than succeeding vertebrae; spinal nerve foramina in atlas and in tail vertebrae; co-ossified scapula and coracoid, with narrow, waisted scapula and large, heavily ossified coracoid plate perforated by supracoracoid foramen; strongly built forelimbs (relatively massive humerus with deep crista ventralis humeri and expanded distal head); radius with expanded distal head; well-ossified tarsus and carpus including fusion of ulnare and intermedium; rib-bearers with conjoined heads throughout the column.

Remarks: Iridotriton differs from the stem-caudates Karaurus , Kokartus and Marmorerpeton in lacking any trace of sculpture on the skull bones, and in having spinal nerve foramina in both the atlas and caudal vertebrae. It resembles the Chinese salamanders Chunerpeton ( Gao & Shubin, 2003) , Jeholotriton ( Wang, 2000a) , Laccotriton ( Gao & Shubin, 2001) , Liaoxitriton ( Dong & Wang, 1998; Wang, 2004) and Sinerpeton ( Gao & Shubin, 2001) in having conjoined surfaces on the rib-bearers and retaining a separate angular in the jaw, but differs from Sinerpeton and Laccotriton in lacking a separate coronoid, and from all five Chinese taxa in having a much more massive humerus. Iridotriton further differs from Chunerpeton in prefrontal shape (shorter and squarer in Chunerpeton ), squamosal shape (waisted below dorsal head in Chunerpeton ), and the ossification of the tarsals and carpals (unossified in Chunerpeton ). It differs from the Cretaceous Valdotriton ( Evans & Milner, 1996) in having a broad rather than spike-like alary process of the premaxilla, a dentary with an open rather than anteriorly closed Meckelian groove, and conjoined rather than double-headed rib-bearers; and differs from Valdotriton , Prosiren , and Apricosiren (S. E. Evans, pers. observ.) in lacking ventromedian keels on the presacral centra. The Cretaceous Hylaeobatrachus is perennibranchiate ( Estes, 1981) whereas Iridotriton is metamorphosed. The Cretaceous Spanish Galverpeton ( Estes & Sanchíz, 1982) is based on a single trunk vertebra distinguished by the presence of a spinal nerve foramen and strong lateral crests, both of which are absent in the Morrison form. Ramonellus from the Early Cretaceous of Israel ( Nevo, 1964; Nevo & Estes, 1969) differs in being very long-bodied (at least 34 presacrals) and in having a long retroarticular process on the lower jaw. Generic distinction for Iridotriton is therefore defensible.

Comonecturoides marshi Hecht & Estes, 1960 , was described from the Morrison Formation at Quarry 9, Como Bluff, on the basis of a single isolated femur and, though clearly caudate, is a nomen dubium since it is restricted to an indeterminate type ( Evans & Milner, 1993). The holotype femur is slightly smaller than that of Iridotriton , has a less projecting trochanter, and a less compressed proximal head.

Description

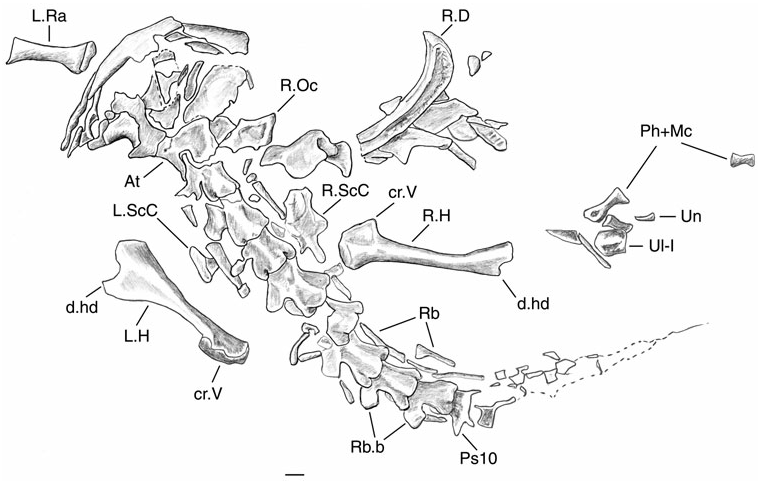

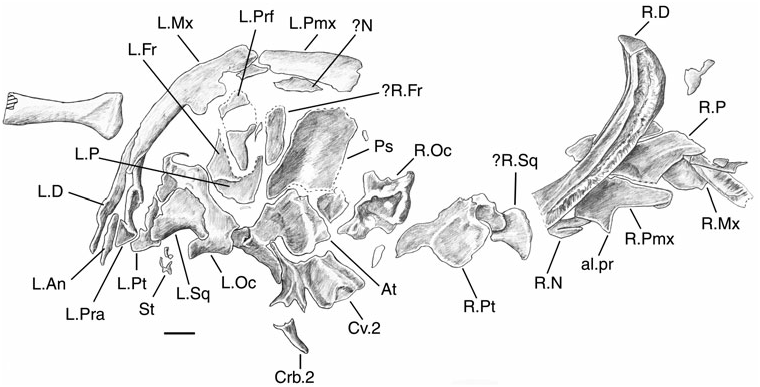

The specimen (DINO 16453a, b) is preserved in articulation and includes much of the skull, the complete presacral axial skeleton, the sacrum, a small set of postsacrals, and parts of the girdles and the limbs. The skull, forelimbs, and anterior presacral series (DINO 16453a) are preserved in dorsal view, but the posterior presacral region and left hind limb are on a small block (DINO 16453b) detached during collection and prepared in ventral view. The specimen is generally well preserved in three dimensions, with the vertebrae fully articulated, but there has been some disarticulation of the limbs and girdles and of parts from the right side of the skull roof and jaws. It is not possible to get an accurate measurement of the snout- sacrum length, but comparison of humeral and femoral lengths with those of similarly proportioned modern analogues suggests a snout- sacrum length of 50– 60 mm, and a total length (with tail) of between 80 The skull

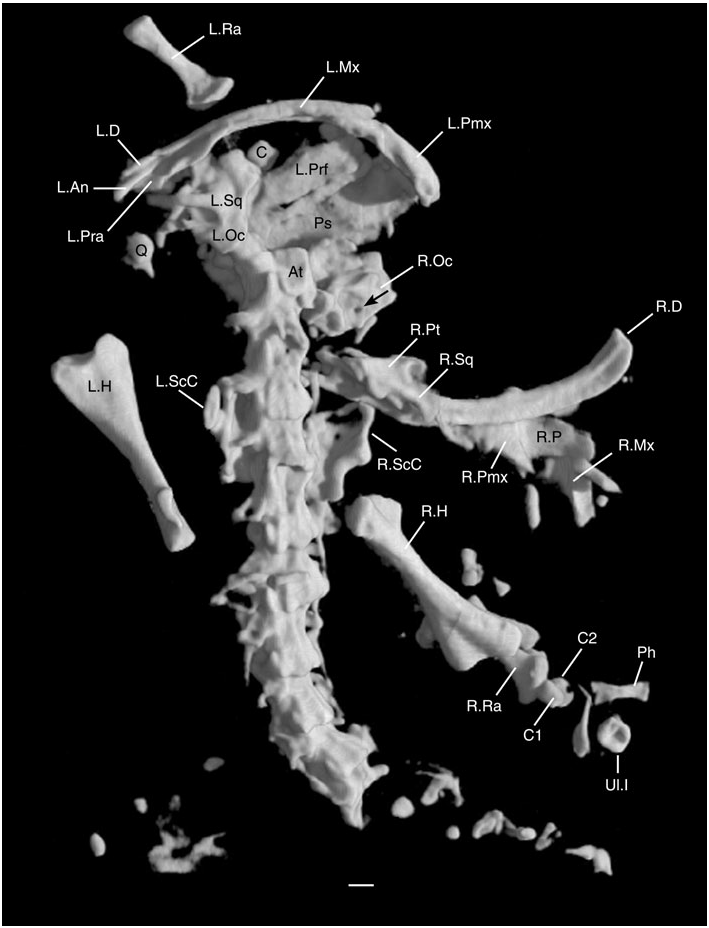

The posterior part of the skull aligns with the vertebral column, but the more anterior half, including the jaws, has rotated to the right ( Fig. 6 View Figure 6 ). Despite this, the bones of the left side are roughly in situ (but telescoped) whereas those of the right have been displaced out to the side of the specimen. A majority of the skull elements can be identified but some of the small bones (lacrimals and septomaxillae, if present) cannot be recognized.

Premaxilla: both bones are preserved, the left in situ and the other displaced and rotated to the right of the specimen. They show an elongated maxillary process that either abuts or underlaps the maxilla. The alary process (processus dorsalis) of the left premaxilla is damaged but the right is complete. It is short, broad, and asymmetric, with a strong lateral angle. A premaxillary tooth count is not possible.

Maxilla: the left bone is also in situ and essentially complete except for the medial edge of its dorsal (facial) process. The bone has an elongate premaxillary process, a short dorsal process, and a slender posterior process. The right bone is adjacent to the right premaxilla but has been rotated so that its lingual surface is exposed. The teeth are damaged and no tooth count is possible.

Nasal: a probable right nasal lies adjacent to the dorsal process of the right premaxilla. It appears to be divided into two parts by a deep cleft (though this could be an artefact of breakage). Division would imply paired nasal anlagen that are in contact posteriorly (as in the Cretaceous Valdotriton ; Evans & Milner, 1996). There is a bone of similar size behind the left premaxilla, but the details are obscured.

and 100 mm overall. Despite this small size, the specimen appears to represent a metamorphosed individual (dermal roofing bones ossified and in position; squamosal full size, all bones of lower jaw ossified, dorsal process of maxilla ossified, vomer fully formed, otic capsule complete and stapes ossified: Rose, 2003).

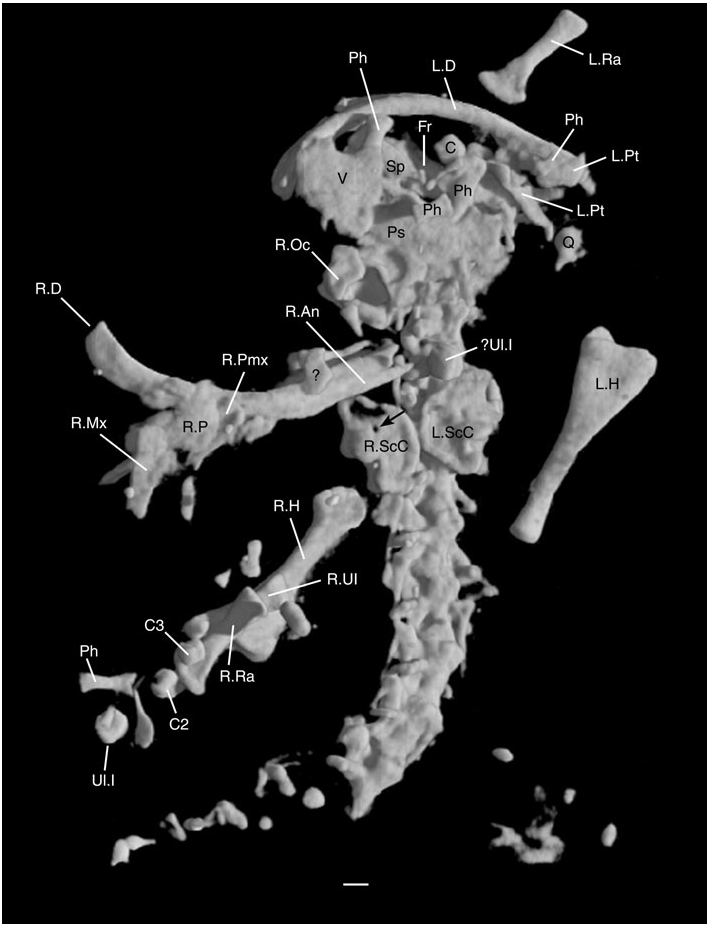

Figures 1–3 View Figure 1 View Figure 2 View Figure 3 show the specimen as preserved on the blocks, but the description that follows also relies on the digital reconstructions from computed tomography ( Figs 4 View Figure 4 , 5 View Figure 5 ).

Prefrontal: a single slender element lies adjacent to the dorsal process of the left maxilla. The identification of this bone as a prefrontal relies on its position to one side of the midline and its posteriorly tapering shape. It is closely similar to the same element in the extant Cryptobranchus and the hynobiid Onychodactylus (S. E. Evans, pers. observ.), and to the reconstructed shape of the Cretaceous Valdotriton ( Evans & Milner, 1996) . The bone is damaged in the midsection but the intervening impression suggests that this is a single bone and there is no trace of any groove or foramen for the lacrimal duct. No lacrimal has been recognized in Iridotriton , but given the telescoping of individual elements, and the various small unidentified elements within the skull mass, we cannot determine whether a lacrimal was present or absent.

Frontals: the left bone is represented by a thin plate deep to the left prefrontal and overlying the left parietal. It is long and relatively narrow, but shows no trace of sculpture and provides no detail of articular surfaces for adjacent bones. The right bone has not been identified with confidence. It may be a partially obscured flat bone, the edge of which is exposed between the left margin of the parasphenoid and the left prefrontal. The frontals appear to have been slightly narrower than the parietals, but of similar length.

Parietals: the left parietal partially underlies the left frontal and prefrontal. The right has been carried out with other bones of this side and lies between the right premaxilla, maxilla, and dentary, extending under the last of these bones for a short distance. The bone is rectangular with at least one (anterior or posterior) straight margin. It is certainly not acutely tapered at either end and therefore probably did not extend far forward under the frontal. Neither parietal is sculptured.

Squamosal: the left bone is in situ, overlapping the braincase medially and the pterygoid distolaterally. It is roughly triangular, broad dorsally and tapers at its ventral tip. The posterior margin is curved. As preserved, the squamosal contacts only the braincase and not the parietal. The right element has not been identified with certainly, but it may be represented by a curved flange underlying the right pterygoid (?R.Sq, Fig. 6 View Figure 6 ).

Vomer: this lies beneath the left jaw symphysis (visible only on the digital reconstructions; V in Fig. 5 View Figure 5 ). If it is the left element, then it is in situ relative to the left dentary, but since the skeleton has partially disarticulated, the two bones have rotated to the left of the frame. The anterior margin [now directed to the left of Fig. 5 View Figure 5 (= right side of body)] has two short surfaces meeting at a slight angle; presumably these met the premaxilla and maxilla. The lateral margin (now at the top) is embayed by the choana and then flares out lateral to it to form a postchoanal flange. The medial margin (now at the bottom) is strongly oblique suggesting the presence of an anterior palatine fontanelle.

Behind it, the posteromedial border (facing to the right of the figure) is relatively long and straight. Teeth are not visible, but this is probably an artefact of the resolution of the high resolution X-ray scanner, because dentary teeth are visible on the specimen but not on the scans (CT slices and reconstructions). An alternative explanation would be that this is the right bone, either turned 180 ∞ on its long axis so that the dorsal surface is exposed, or reversed so that the wider edge, now posterior, met the jaw margin, with the bone narrowing posteriorly (a better match for that of primitive living salamanders like cryptobranchids and hynobiids, S. E. Evans, pers. observ.). Conceivably, it could be the left element, rotated both anteroposteriorly and dorsoventrally. No other bone shows such a radical displacement, but the vomers could have been seriously disrupted when the jaws were disarticulated and rotated outwards.

Pterygoid: the left pterygoid is largely obscured by the overlying squamosal in dorsal view, and by parts of the braincase ventrally. A distinct blade, presumably the posterolateral pterygoid process, extends ventrally beyond the squamosal and quadrate towards the lower jaw, whereas a more fragmentary process is directed anteriorly. From the underside of the specimen (digital reconstructions, Fig. 5 View Figure 5 ), the bone appears more complex, and the medial surface was probably concave, but it is neither large nor strongly expanded. The right pterygoid may be represented by the irregular bone mass adjacent to the right otic elements. It is clearly bent in more than one plane, and curves around the edge of the mandible. Overlying it on the underside is a small, unidentified bony plate that also overlaps the jaw.

Parasphenoid: this has a long parallel-sided anterior rostrum that is overlapped ventrally by the vomer. Posteriorly, at the level of the braincase, the bone expands slightly to overlap the otic capsules, although there are no strong alae and no visible perforations for the internal carotid arteries. Dorsally, the parasphenoid forms the right boundary of the skull mass, and its dorsal surface is concave.

Quadrate: visible on the digital reconstructions as a small dense mass of bone displaced to the left side of the skull.

Braincase: in salamanders, this has two principal components: the sphenethmoid (= orbitosphenoid; Trueb, 1993) that underlies the frontal and attaches to the dorsal margin of the parasphenoid rostrum, and the otic capsule made up of the prootic, opisthotic, and exoccipital, or some combination of these three elements ( Trueb, 1993). The sphenethmoid seems to be represented in Iridotriton by a long narrow element wedged between the skull roof (left frontal) and the parasphenoid rostrum on the left side ( Fig. 5 View Figure 5 ). It is perforated by a small foramen (perhaps for a branch of the ophthalmic division of the trigeminal nerve; Francis, 1934) and has a larger posterior notch for the optic nerve (these structures lie to the left and right of ‘Sp’, respectively, in Fig. 5 View Figure 5 , and are seen most clearly if the digital reconstructions are rotated).

The otic capsule is preserved on both sides of the skull. Its components are fused into a relatively large, rounded structure that extended beyond the confines of the parietal table. On the left side, the exoccipital is roughly in situ against the atlantal cotyle, although it has rotated laterally so that the exoccipital condyle has disarticulated from the atlas. The otic capsule continues forward as a single unit into the prootic, with the squamosal overlapping the lateral and dorsolateral surfaces but not reaching the level of the parietal.

Seen in ventral view ( Fig. 5 View Figure 5 ), the otic capsule surrounds a rather bulbous vestibular cavity. The fenestra ovalis opens ventrolaterally and contains fragments of bone that probably pertain to the stapes. On the right side of the skull, the otic capsule is displaced and has rotated slightly. The opisthotic component is united with the exoccipital and prootic, but is delimited by sutures (although these must be at least partially closed as there is no displacement). Dorsally, the opisthotic (right otic capsule, Fig. 4 View Figure 4 ) exposes a small distinct foramen (small arrow, Fig. 4 View Figure 4 ) that opens from the inside of the vestibular cavity. This foramen is presumably for the endolymphatic duct ( Francis, 1934).

Mandible

The left mandible is in articulation with, and largely obscured by, the maxilla and premaxilla of that side. The right mandible is displaced and exposed in lingual view to the side of the specimen.

The dentary has a narrow but relatively deep terminal symphysis and a long, but very narrow, Meckelian sulcus that is open throughout its length. The alveolar margin is separated from the subdental ridge by a deep groove, so that the tooth-bearing part of the jaw forms a rather shallow margin along the dorsal edge of the dentary. It bears a row of around 40 slen- der pedicellate teeth, but the tooth crowns are not clearly preserved in any position. On both sides, the dentary extends to the posterior end of the mandible, bracing the accessory bones from the labial side.

Between the rear of the dentary and the maxilla on the left side there are two distinct anteroposteriorly directed structures ( Figs 4 View Figure 4 , 6 View Figure 6 ). The more laterally placed of these is a narrow lamina with a thickened margin. It corresponds in structure and position to the angular in the living Cryptobranchus and hynobiids. The more medial structure has a dorsally expanded anterior coronoid process and a posterior edge that curves medially. It then continues ventrolaterally into a flange-like blade that lies parallel to the posterior pterygoid lamina. This is the prearticular-coronoid. On the right mandible, the angular is in situ at the rear of the bone, whereas the slender anterior tip of the prearticular is visible within the posterior half of the Meckelian canal ( Fig. 5 View Figure 5 ).

Axial skeleton

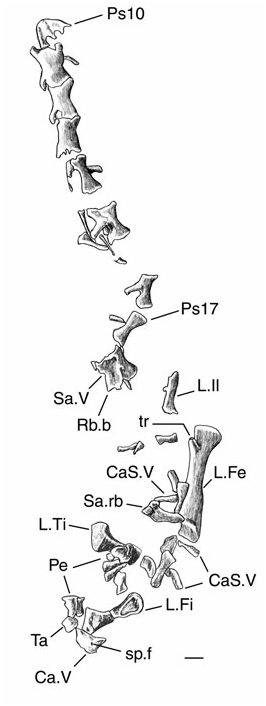

The axial skeleton is preserved in two parts. In 16453a ( Figs 2 View Figure 2 , 4 View Figure 4 , 5 View Figure 5 ), the atlas is preserved in situ. Following it are eight complete vertebrae, fragments of a ninth (Ps 10, Fig. 2 View Figure 2 ), and then impressions and fragments of a further four. Specimen 16453b ( Fig. 3 View Figure 3 ) preserves eight presacral vertebrae followed by a sacral, at least three caudosacrals, and one further isolated caudal. It is difficult to be certain of the relationship of the two blocks, but it seems likely that the first vertebrae preserved on 16453b (Ps10, Fig. 3 View Figure 3 ) is part of the last vertebra on block 16543a, with the vertebrae following on 16453b responsible for the impressions on 16453a. Under this interpretation, there were a total of 17 presacrals. There may have been more, but there cannot have been fewer.

Atlas: this is preserved in dorsal and left lateral views but is otherwise obscured by the bones around it. Thus the presence of the interglenoid tuberosity cannot be confirmed, although, judging from the other features of the skeleton, it is likely to have been present in a caudate of this grade. The atlas is slightly shorter than the vertebra following it, and had a low neural arch with a midline crest but no spine, and a convex posterior margin. Anteriorly, the left cotyle remains in articulation with the exoccipital condyle. In lateral view, however, crushing obscures the detail. There is certainly at least a notch in the anterior margin of the atlas for the first spinal nerve (between the cotyle and the anterodorsal margin of the arch, Fig. 6 View Figure 6 ), but whether it was a fully enclosed foramen or not is impossible to judge.

Postatlantal presacral vertebrae: the first eight postatlantal vertebrae have low neural arches with a middorsal keel and short horizontal spines that were directed posteriorly and were probably completed in cartilage (judging by the pitted distal tips). Ventrally, the centrum is rounded with no midline keel and only small anterior basapophyses. The centra form weak amphicoelous cylinders that probably developed ectochordally. There is no evidence of spinal nerve foramina in trunk vertebrae. The zygapophyses are strong and horizontal, whereas the rib-bearers are long and directed posterolaterally. On each, the dorsal and ventral rib facets have coalesced to form a single head, although there is a slight waisting of the surface in more posterior vertebrae. The ribs themselves are certainly single-headed and relatively long (equal or nearly equal to the length of the centrum). Most are very gracile, but the second and third postatlantal vertebrae bear more robust ribs for the support of the pectoral girdle. The centra of the posterior presacrals (16453b, Fig. 3 View Figure 3 ) are also simple and spool-like, with neither median keels nor prominent basapophyses. At most, there is a slight bilateral thickening of the surface in the region of the basapophyses. The rib-bearers become weaker towards the sacrum.

Sacral vertebra: the sacral is separated from the last trunk vertebra and has rotated slightly, probably because of its relatively massive rib-bearers and the influence of the pelvic girdle and hind limb. The sacral ribs themselves have disarticulated and one is visible beside the femur.

Caudosacral vertebrae: behind the sacral vertebra and under the pelvic region, there are three caudosacrals but they are preserved only in ventral view and yield little detail – except for the presence of ribbearers and free ribs similar to those of the last trunk vertebrae.

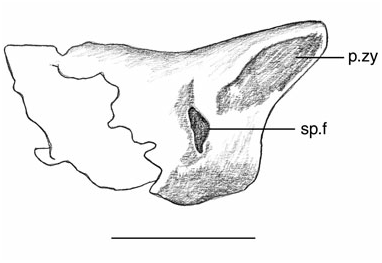

Caudal vertebrae: one isolated caudal is preserved at the edge of the block ( Fig. 7 View Figure 7 ). This small vertebra has no spine and weak zygapophyses, but preserves a spinal nerve foramen in its posterior half.

Pectoral girdle and forelimb

Scapulocoracoid: the right and left scapulocoracoids are in situ, but partially obscured by the overlying vertebrae and ribs. They are therefore most clearly seen in the digital reconstructions ( Figs 4 View Figure 4 , 5 View Figure 5 ). The scapula and coracoid form a single ossification. The coracoids are robust semicircular plates that curve under the axial skeleton and are each perforated by a single supracoracoid foramen (clearest on the right, Fig. 5 View Figure 5 ). There is no coracoid incisure and the two plates were almost in contact medially.

The scapula component is clearly visible in dorsal view ( Fig. 4 View Figure 4 , left side) and is small in relation to the coracoid. The upper margin is straight and the anterior and posterior margins are strongly curved so that the narrow scapular blade is strongly waisted at its junction with the coracoid. The top of the blade is broken away on the right side. As preserved, the glenoid is posterolateral in position, and deep, with its long axis orientated dorsoventrally. This suggests a degree of dorsoventral movement for the large humerus, as occurs in some modern salamanders in slow-gait terrestrial locomotion ( Evans, 1946). Among modern salamander scapulocoracoids examined, the morphology of Iridotriton most closely resembles that of the terrestrial Ambystoma (S. E. Evans, pers. observ.).

Humerus: both humeri are preserved. The proximal and distal heads are at roughly 90 ∞ to one another, and the distal head is relatively massive compared to the slender humeral shaft. The proximal end bears an expanded crista ventralis humeri but no crista dorsalis. At the distal end, the condyles for articulation with the radius and ulna are not ossified, and it is clear from the embayed shape of the distal end that it bore a large cartilaginous joint surface.

Radius and ulna: the left radius lies adjacent to the left maxilla ( Figs 2 View Figure 2 , 4 View Figure 4 , 5 View Figure 5 ), whereas the right radius and ulna are visible only on the digital reconstructions ( Figs 4 View Figure 4 , 5 View Figure 5 ). Both bones have relatively narrow shafts and expanded ends, although the ulna is the more gracile element. They are roughly half the length of the humerus (R/H = 53%).

Carpus and manus: wrist and manus elements are preserved on both sides, but are disarticulated. There is one isolated carpal, probably from the left side, just behind the left dentary ( Fig. 5 View Figure 5 ). On the right side, three carpal elements are clearly preserved (digital reconstructions, Figs 4 View Figure 4 , 5 View Figure 5 ), three (C1-3, Figs 4 View Figure 4 , 5 View Figure 5 ) lie clustered around the distal ends of the ulna and radius, whereas a single, slightly larger element (Ul.I) is positioned further distally, close to a phalanx. This large rounded element has a small central perforation and matches the fused ulnare + intermedium of living salamanders ( Francis, 1934; S. E. Evans, pers. observ.).

According to Francis (1934) the short canal marks the line of fusion between the two bones and conveys the perforans carpi artery (a second similar element lies in front of the left scapulocoracoid, Fig. 5 View Figure 5 ). The three smaller carpals cannot be identified with any confidence. In the extant Salamandra ( Francis, 1934) , there are four ossified carpals in addition to the ulnare-intermedium: a centrale, a basale commune (representing a fusion of the first two distal carpals), and then a basale 3 and a basale 4, although more elements occur in some taxa.

Of the three distal elements in Iridotriton , C1 is the smallest and may be a basale; C2 is strongly concave along its long axis and could be a centrale. C3 is more cylindrical, with a small constriction around the midpoint. It is either another basale, or possibly a basale commune. If this latter is correct, then the carpal structure of Iridotriton (fused ulnare-intermedium, large basale commune, small number of well ossified distal carpals/centrale) would be relatively derived. The phalangeal formula cannot be reconstructed: none of the digits is complete on the right side, and the phalanges of the left manus are scattered amongst the bones of the skull. Overall, however, the forelimb is robust and strongly ossified.

Pelvic girdle and hindlimb

Parts of the left hind limb and girdle are preserved but disarticulated.

Ilium: the left ilium is seen in medial view thus obscuring the structure and size of the acetabulum. The bone is small in comparison to the femur (although this is exaggerated in Fig. 3 View Figure 3 by the edge-on view) and quite gracile. There is no trace of either ischiadic plate and these are presumably deep in the matrix (although this second block was not scanned).

Femur: this is of similar length to the humerus, but less robust. The proximal and distal heads are somewhat compressed and there is a distinct projecting proximal trochanter.

Tibia and fibula: as in the forelimb, the epipodials are short and stout, with the tibia the more robust of the two elements.

Tarsus and pes: a small number of scattered bones of the foot (metatarsals and short phalanges) are also preserved. The elements of the pes are larger and longer than those of the manus but the phalangeal formula cannot be reconstructed. There is one element beside the caudal vertebra that may be a tarsal.

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.