Albanerpeton nexuosus Estes, 1981

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.5378709 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/038C6153-2824-FFEE-FF4E-FD7FFEE2FB15 |

|

treatment provided by |

Marcus |

|

scientific name |

Albanerpeton nexuosus Estes, 1981 |

| status |

|

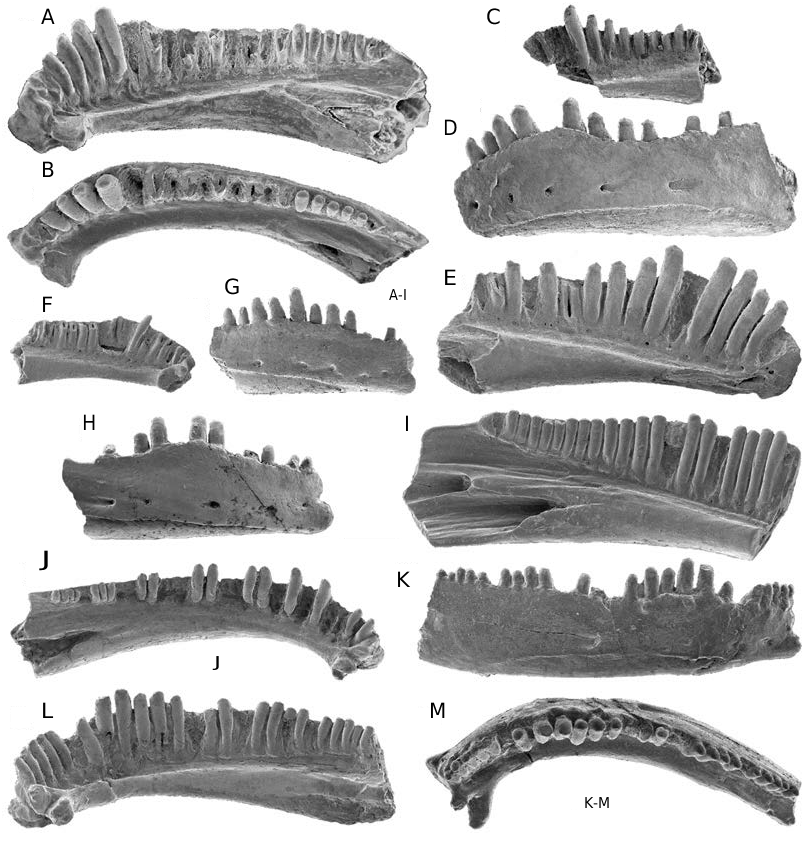

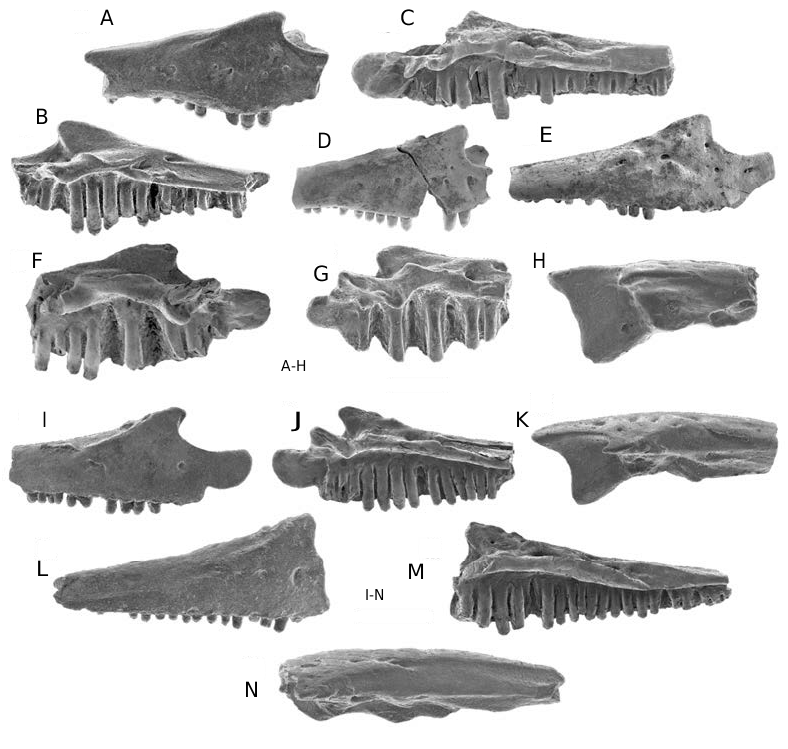

Albanerpeton nexuosus Estes, 1981 ( Figs 2 View FIG A-I; 3A-H; 5; 6A-E; Tables 2; 3)

Prodesmodon copei Estes, 1964: 88-96 , figs 43; 44 (in part: referred jaws and femur subsequently assigned by Estes [1981] to Albanerpeton nexuosus )

Albanerpeton nexuosus Estes, 1981: 24 , fig. 3H-K (original description)

“ Albanerpeton n. sp. A Estes” Fox & Naylor 1982: 120 “ Albanerpeton sp. A ” Fox & Naylor 1982: table 1 Albanerpeton galaktion Fox & Naylor, 1982: 121-127 , figs 2d, e, 3d, e (in part: nine referred, catalogued jaws here transferred to A. nexuosus )

Albanerpeton ? nexuosus (Estes) McGowan 1998: 191 ? Albanerpeton nexuosus (Estes) Rage & Hossini 2000 HOLOTYPE. — UCMP 49547, nearly complete left dentary lacking posterior end and having about 24 teeth and four empty tooth slots (Estes 1964: fig. 44a, c). The holotype is missing and presumed lost (P. Holroyd, pers. comm. 1996).

HOLOTYPE HORIZON AND LOCALITY. — Upper Cretaceous ( upper Maastrichtian ; i.e. Lancian in age) Lance Formation ; UCMP V-5620, Niobrara County, Wyoming.

REFERRED SPECIMENS. — Deadhorse Coulee Member, Milk River Formation. Seven localities, Alberta: UALVP MR-2: UALVP 40007, dentary; UALVP MR-4: UALVP 39953, 39954, premaxillae; UALVP 40000, 40001, 40008, dentaries; UALVP 39994, frontals; UALVP MR-6: UALVP 39955-39959, premaxillae; UALVP 16209, 39971, fused premaxillae; UALVP 16239, 39973-39975, maxillae; UALVP 16220, 39998, 39999, 40003-40006, 40009-40011, 40015-40021, 40032, dentaries; UALVP 39984, 39987, 39989-39993, 39996, frontals; UALVP MR- 8: UALVP 16253, premaxillae; UALVP MR-9: UALVP 16254, 39960, premaxillae; UALVP 39997, dentaries; UALVP MR-12: UALVP 16207, 16208, premaxillae; UALVP 39961, fused premaxillae; UALVP 39976, 39977, maxillae; UALVP 39983, 39988, 43812, frontals; UALVP MR-20: UALVP 39962-39970, premaxillae; UALVP 16206, 39972, fused premaxillae; UALVP 16242, 39978-39982, maxillae; UALVP 16237, 16238, 40002, 40012- 40014, 40022, dentaries; UALVP 39985, 39986, 39995, frontals.

Oldman Formation. Two localities, Alberta: RTMP L0406: RTMP 95.177.15, dentary; RTMP L1127: RTMP 96.78.152, dentary.

Kaiparowits Formation. Two localities, Utah: OMNH V6: OMNH 60245, maxilla; OMNH V61: OMNH 23964, dentary.

Aguja Formation. OMNH V58/ TMM 43057, Texas: OMNH 25345, 60238, premaxillae; OMNH 60239, maxilla; OMNH 25235, 25238, 60240, 60241, 60243, 60244, dentaries.

Upper Fruitland Formation or lower Kirtland Formation. KUVP NM-37, New Mexico: KUVP 129739, dentary.

Hell Creek Formation. Bug Creek Anthills, Montana: UALVP 40035, dentary.

Lance Formation. Three localities, Wyoming: UCMP V-5620 ( holotype locality): UCMP 49535, 49538 (now lost), 49540 dentaries ; UCMP V-5711: AMNH 15259 About AMNH , 22950 About AMNH , 22951 About AMNH , 22955 About AMNH , 22959 About AMNH , 27177 About AMNH , dentaries ; UW V-79032: UW 14587 , maxilla ; UW 14584 , 15019 , dentary .

Laramie Formation. UCM locality 77062, Colorado: UCM 38713, premaxilla ; UCM 38714, dentary .

DISTRIBUTION ( Table 1). — Upper Cretaceous (Campanian and Maastrichtian), North American Western Interior: lower Campanian (Aquilan in age): Deadhorse Coulee Member, Milk River Formation, Alberta ; middle Campanian ( Judithian in age): Oldman Formation , Alberta ; Kaiparowits Formation, Utah ; and Aguja Formation, Texas ; upper Campanian or lower Maastrichtian (Edmontonian in age): upper Fruitland Formation or lower Kirtland Formation , New Mexico ; upper Maastrichtian ( Lancian in age): Hell Creek Formation, Montana ; Lance Formation, Wyoming ; Laramie Formation, Colorado .

REVISED DIAGNOSIS. — Large-bodied species of Albanerpeton differing from congeners in the following autapomorphies: boss on premaxilla covers about dorsal one-half of pars dorsalis; premaxillary ornament consists of polygonal pits enclosed by ridges arranged in a reticulate pattern; dorsal flange on lingual edge of maxillary process on premaxilla prominently expanded dorsally and continuous labially with base of lateral internal strut; teeth on maxilla and dentary strongly heterodont in size anteriorly; and occlusal margins of pars dentalis on maxilla and dental parapet on dentary sinuous in labial outline, with apex adjacent to longest teeth. Most closely resembles A. inexpectatum and unnamed Paleocene species, but differs from other congeners, in the following synapomorphies: premaxilla robustly constructed, variably fused medially, with pars dorsalis short and strongly sutured dorsally with nasal; maxilla with relatively short premaxillary lateral process; and frontals with internasal process relatively narrow and acuminate or spike-like in dorsal or ventral outline. Primitively differs from A. inexpectatum in having maxilla and dentary unornamented labially, dentary lacking dorsal process behind tooth row, and fused frontals relatively narrower in dorsal outline, with ventrolateral crest relatively narrower and ventral face less concave dorsally; from unnamed Paleocene species in having premaxilla with prominent palatine process and inferred larger body size; and from both species in having premaxilla with boss present and ornament limited dorsally on pars dorsalis and in having maxilla with anterior end of tooth row in front of leading edge of nasal process.

DESCRIPTION

Of the 13 topotypic specimens attributed by Estes (1981) to Albanerpeton nexuosus , only the holotype (UCMP 49547) and three referred dentaries (UCMP 49535, 49538, and 49540) can be assigned with any confidence to the species. The remaining topotypic jaws (four dentaries, two maxillae, and two premaxillae) are not identifiable below the familial level, as noted above, whereas the topotypic femur belongs to an indeterminate salamander (see Remarks below). Jaws and frontals from elsewhere in the Western Interior can be referred to the species. Many of these non-topotypic specimens come from the Milk River Formation and include nine jaws (UALVP 16206-16209, premaxillae; UALVP 16239, 16242, maxillae; 16220, 16237, 16238, dentaries) previously listed by Fox & Naylor (1982:121) for A. galaktion . Unless stated otherwise, descriptions below are composites.

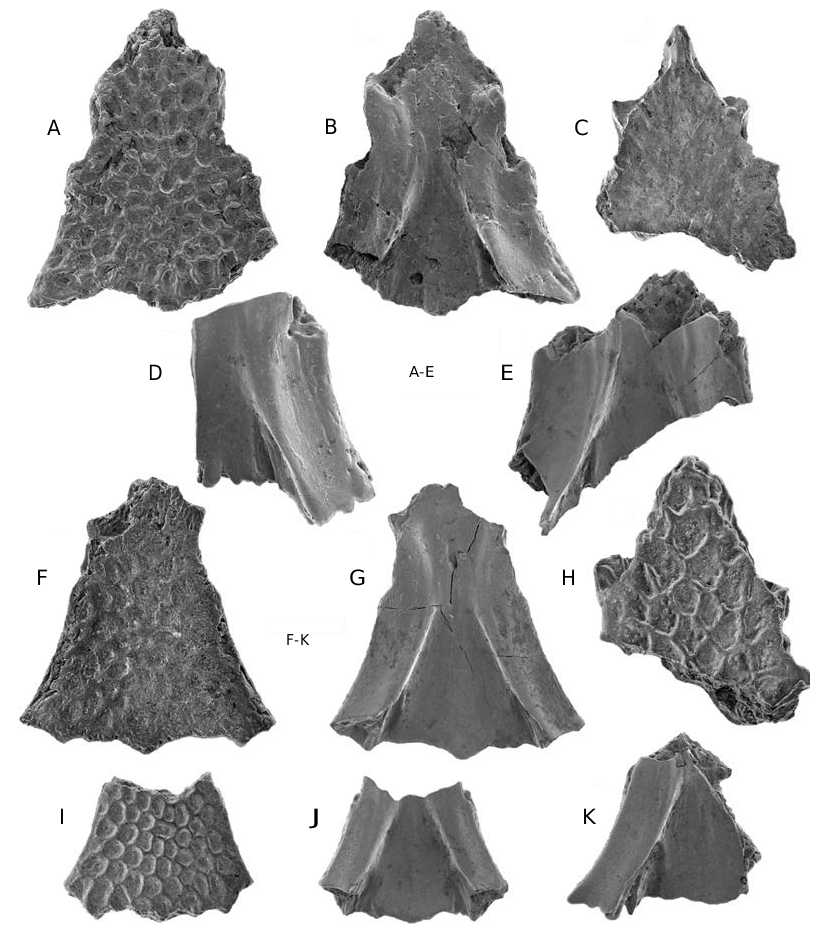

Premaxilla ( Fig. 5 View FIG ; Tables 2; 3)

Twenty-six specimens are available from the Milk River Formation and these adequately document the structure of the premaxilla. The bone is robustly constructed and the largest specimen, an isolated premaxilla (UALVP 16207; not figured), is about 3.5 mm high. Five pairs of premaxillae, including UALVP 16206 ( Fig. 5 View FIG A-C) are solidly fused along the midline. Each fused pair retains a faint median line of fusion lingually and UALVP 16209 (Fox & Naylor 1982: fig. 2e) also preserves an incomplete line of fusion labially. Other premaxillae are isolated, but because the medial flange is broken on many of these specimens it is uncertain, as Fox & Naylor (1982) noted, whether the premaxillae in life were sutured medially (i.e. paired) or lightly fused and fell apart after death. UALVP 39955 ( Fig. 5D, E View FIG ) preserves a nearly complete medial flange that is medially narrow and extends down the medial edge of the bone along the lower two-thirds of the pars dorsalis onto the upper one-half of the pars dentalis. Sizes of fused and unfused premaxillae overlap considerably, more so than in Albanerpeton inexpectatum (Gardner 1999d) . This implies that if premaxillae also fused ontogenetically in A. nexuosus , the timing of fusion was more variable. The pars dorsalis is moderately low and broad ( Tables 2; 3). The dorsal edge of the process bears well-developed ridges and grooves, indicating it was strongly sutured with the nasal. The lacrimal notch is typically deep and wide, but these dimensions vary considerably (cf. Fig. 5B, D View FIG ) in both absolute and relative terms ( Tables 2; 3), independent of size. The notch is narrowest in the two pairs of fused premaxillae (UALVP 16206 and 16209) that preserve an intact pars dorsalis. Labially, the pars dentalis and the lower one-half of the pars dorsalis are perforated by small, scattered, external nutritive foramina. The dorsal one-half of the pars dorsalis is covered by a prominent, raised boss set off from the rest of the process by a thick ventral rim. The boss is best developed on UALVP 16206 ( Fig. 5A View FIG ). On this specimen, the boss is continuous across the two halves of the fused premaxillae. The external face of the boss is flattened and prominently ornamented with narrow ridges that are arranged in a reticulate pattern and enclose broad, flat-bottomed, polygonal pits. Given that essentially identical pits on the dorsal surface of albanerpetontid frontals and parietals each housed a dermal ossicle (McGowan & Evans 1995), it is probable that each of the pits on the premaxillary boss in A. nexuosus also contained an ossicle.

In lingual view, the suprapalatal pit opens about midway across the pars dorsalis and is located low on the pars dorsalis ( Fig. 5B, D View FIG ), with the ventral edge of the lingual opening of the pit continuous with, or slightly dorsal to, the dorsal face of the pars palatinum. Specimens broken across the pars dorsalis ( Fig. 5H View FIG ) show that the floor of the pit is formed by the pars palatinum. The suprapalatal pit is ovoid to elliptical in lingual outline and moderate in size ( Table 2), accounting for 0.09- 0.13 (n = 8) of the lingual surface area of the pars dorsalis. Only one internal strut is present, lateral to the suprapalatal pit. This strut is perforated laterally by one large and, often, one or two smaller foramina ( Fig. 5E View FIG ), all opening medially inside the suprapalatal pit. The strut is mediolaterally broad and expands lingually as it descends down the lingual face of the pars dorsalis. The base of the strut continues linguolaterally across the dorsal surface of the pars palatinum as a low, rounded ridge that grades into the unnamed dorsal process (see below) on the posterior edge of the maxillary process.

The pars palatinum is expanded lingually ( Fig. 5C, F, G View FIG ) and bears prominent palatine and maxillary processes with shallow, lingual facets for contact with one or more palatal bones. Medial edges of the palatine processes are solidly fused in the five fused pairs of premaxillae ( Fig. 5C, F View FIG ); by contrast, these processes are at best only weakly fused in azygous premaxillae of Albanerpeton inexpectatum . The unnamed dorsal process, mentioned above, on the lingual edge of the maxillary process is prominently developed into a raised, labiolingually-compressed flange that is dorsally convex in lingual outline. The unnamed process on the ventral surface of the maxillary process is low, ventrally convex, and varies from a drumlin-shaped knob (e.g., UALVP 16206; Fig. 5C View FIG ) to a short ridge (e.g., UALVP 39971; Fig. 5F View FIG ). The palatal foramen ( Fig. 5F, H View FIG arrow 1) is small, with a diameter no more than three-quarters the diameter of the medial teeth and usually considerably less. The canal connecting the dorsal and ventral openings of the palatal foramen extends dorsoventrally through the pars palatinum. The foramen opens ventrally in the pars palatinum in line with the third to fourth tooth positions, just lingual to the junction with the pars dentalis, and dorsally in the pars palatinum at, or slightly inside, the opening of the suprapalatal pit. One or two smaller unnamed foramina ( Fig. 5G, H View FIG arrow 2) penetrate the bone well labial to the palatal foramen, ventrally in the junction between the pars palatinum and pars dentalis and dorsally in the floor of the suprapalatal pit. Differentiating foramina in the ventral surface of the pars palatinum can be difficult in specimens in which the ventral opening of the palatal foramen is unusually small and close to the labial limit of the pars palatinum. This is especially true for UALVP 16206 ( Fig. 5C View FIG ), a specimen for which I have not been able to reliably identify the ventral opening of the palatal foramen on either the left or right side. Tiny foramina may perforate the lingual face of the pars dentalis above the tooth bases.

Three incomplete left premaxillae, two (OMNH 25345 and 60238; Fig. 5I, J View FIG , respectively) from the Aguja Formation and one (UCM 38713; Fig. 5K View FIG ) from the Laramie Formation can be referred to Albanerpeton nexuosus based on resemblances to specimens from the Milk River Formation. These geologically younger specimens provide no further details about premaxillary structure in the species.

Maxilla ( Fig. 3 View FIG A-H)

None of the 12 specimens from the Milk River Formation and one specimen each from the Aguja , Kaiparowits , and Lance formations are complete, but collectively they document most of the structure of the maxilla except for the posterior end. The most nearly complete specimen is UALVP 16242 ( Fig. 3A, B View FIG ), a right maxilla broken posteriorly behind the sixteenth tooth position and anteriorly across the premaxillary lateral process and anterior edge of the premaxillary dorsal process. The largest specimen, UALVP 39973 ( Fig. 3C View FIG ), is about 5.3 mm long and would have been slightly longer than 6 mm when complete. The bone is unornamented labially, except for small external nutritive foramina scattered across the anterior one-third ( Fig. 3A, D, E View FIG ). As in other albanerpetontids, the nasal process is triangular in labial outline and the pars facialis is low, becoming shallower posterior from the nasal process. The ventral edge of the pars dentalis is sinuous in labial outline, being ventrally convex and deepest labial to the longest teeth ( Fig. 3A, D View FIG ). Damage to the ventral edge of the pars dentalis in some specimens (e.g., UALVP 39973 ; Fig. 3C View FIG ) creates the impression that this edge is more nearly straight. The anterior end of the tooth row lies several loci anterior to the point of maximum indentation along the leading edge of the nasal process .

The premaxillary process is anteriorly short (length subequal to height at base) and obtuse in lingual outline, with a nearly truncate to slightly round- ed anterior margin (cf. Fig. 3E View FIG versus F, G). The lingual surface of the process on larger specimens is roughened for contact with the complementary facet on the premaxilla. The premaxillary dorsal process is broad ( Fig. 3H View FIG ) and ventrally bears a transverse ridge, best developed on larger maxillae ( Fig. 3F View FIG ), that in life abutted against the posterior edge of the maxillary process on the premaxilla. The pars palatinum is broad lingually, tapers towards its posterior end, and dorsally bears a raised, saddle-like bony patch for contact with the base of the lacrimal and a trough more lingually for contact with one or more unknown palatal bones. The internal narial margin spans four or five tooth positions.

Dentary ( Fig. 2 View FIG A-I)

Fifty-two dentaries are available from seven formations, but none of these are as nearly complete as the two figured and now lost topotypic dentaries ( UCMP 49547 and 49538). Published figures show that the holotype ( UCMP 49547 ; Estes 1964: fig. 44a, c) was a nearly complete left dentary that lacked only the posteriormost part of the area for attachment of the postdentary bones, whereas UCMP 49538 (Estes 1964: figs 43e; 44b) was a less nearly complete right dentary broken immediately behind the posterior end of the tooth row. One of the surviving topotypic jaws, a right mandible ( UCMP 49540 ; Fig. 2A, B View FIG ), consists of the anterior tip of the angular in articulation with an incomplete dentary. Although the latter bone in UCMP 49540 lacks the distal end of the symphyseal prong, much of the area for attachment of the postdentary bones, and the posteriormost end of the tooth row, it remains the most nearly complete dentary currently available for Albanerpeton nexuosus . Several dentaries, including UCM 38714 ( Fig. 2D, E View FIG ) are from slightly larger individuals and I estimate a maximum dentary length of about 10 mm for the species. The dentary is robustly constructed, even in small specimens. The dentary is unornamented labially and a row of rarely more than six external nutritive foramina extends along the anterior oneto two-thirds of the bone. The ventral scar and ridge for attachment of the intermandibularis muscles are prominently developed, particularly on larger dentaries. In contrast to the typical albanerpetontid condition, the dorsal edge of the dental parapet is sinuous in labial or lingual outline: the parapet is highest about one-third of the distance along the tooth row from the anterior end, lingual to the tallest teeth, and descends anteriorward and posteriorward from this region. Adjacent to the highest teeth, the dorsal edge of the parapet varies from dorsally convex to angular in labial or lingual outline. Smaller dentaries also exhibit this sinuous pattern ( Fig. 2C, F, G View FIG ). Dentaries from the Milk River Formation suggest that the profile of the dorsal edge of the parapet changed from convex to angular with growth (cf. Fig. 2G, H View FIG ). This pattern may not hold true for geologically younger individuals, because the dorsal edge of the dental parapet is already angular in outline on the two smallest dentaries ( UCMP 49535 and RTMP 96.78.152; Fig. 2C, F View FIG , respectively) from elsewhere. No dorsal process is present behind the tooth row ( Fig. 2I View FIG ). The symphyseal eminence is prominently developed and one or two symphyseal prongs occur on either the left or right dentary. The remainder of the lingual structure is typical for albanerpetontids in having the subdental shelf shallow and gutter-like anteriorly, becoming deeper anteriorly, the Meckelian canal closed posteriorly, and a broad area of attachment posteriorly for the postdentary bones .

Dentition ( Figs 2 View FIG A-I; 3A-G; 5A-G, I-K)

As in all albanerpetontids, the marginal teeth are straight, highly pleurodont, non-pedicellate, and have labiolingually compressed, chisel-like, and faintly tricuspid crowns. Teeth on different jaws range from short, robust, and widely spaced to more elongate, gracile, and closely spaced (cf. Fig. 5B, D View FIG ). This variation occurs independent of the size or geological age of jaws. Premaxillae with a complete tooth row have eight (n = 4) or nine (n = 5) loci. No maxilla available to me has an intact tooth row: UALVP 39973 ( Fig. 3C View FIG ) and 39977 ( Fig. 3E View FIG ) preserve the anterior 17 and 18 tooth positions, respectively, and I estimate that each bone probably held about 25 loci when complete. Figures of UCMP 49538 (Estes 1964: fig. 43e) and 49547 (Estes 1964: fig. 44c) indicate that these now lost topotypic dentaries had complete tooth rows with, respectively, about 24 and 28 tooth positions. Of the dentaries at hand, UCMP 49540 has the most nearly complete tooth row, with the anterior 23 loci preserved. Unlike other congeners, teeth are markedly heterodont in size anteriorly on the maxilla and dentary. Teeth are longest about one-third of the distance along the tooth row, typically at the fourth to sixth loci on the maxilla and the sixth to ninth loci on the dentary. As this markedly heterodont pattern occurs in small dentaries ( Fig. 2C, F View FIG ) it can be expected in small maxillae as well, although no examples of the latter are known. Ample evidence for tooth replacement occurs in the form of tooth slots for replacement teeth, a lingual resorption pit in the base of the occasional tooth, and, in rare specimens, a replacement crown in situ within a tooth slot.

Frontals ( Fig. 6 View FIG A-E)

Frontals have not previously been described for Albanerpeton nexuosus . Here I refer to the species 15 incomplete specimens from the Milk River Formation. The two most nearly complete of these are UALVP 39996 and 39983. UALVP 39996 ( Fig. 6A, B View FIG ) is a crushed pair of frontals that is missing the distal ends of the internasal and anterolateral processes, the posterior end of the ventrolateral crest on both sides, and much of the posterior edge of the frontal roof. The specimen is about 5 mm in preserved midline length and was probably nearly 6 mm long when the bone was complete. UALVP 39983 ( Fig. 6C View FIG ) is the anterior three-fifths of an uncrushed pair of frontals from an individual of about the same size. Several specimens (e.g., UALVP 39989 and 39987; Fig. 6D, E View FIG , respectively) were from larger individuals and I estimate that when complete these frontals approached 7 mm in midline length. Frontals are solidly fused along the midline, triangular in dorsal or ventral outline, and longer than wide. The ratio of midline length to width across the posterior edge between the lateral edges of the ventrolateral crests is about 1.25 in UALVP 39996 , as preserved, but would have been less when the bone was complete. The internasal process, preserved on four specimens and complete on two of these ( UALVP 39983 and 43812), is slightly longer than wide and acuminate or spike-like in dorsal outline. The groove along the lateral face of the process for contact with the nasal, the two pairs of slots for receipt of the nasal and prefrontal, and the anterolateral processes are all well developed. The dorsal and ventral edges of the more posterior slot for receipt of the prefrontal are moderately excavated medially. Posterior from the base of the anterolateral process, the lateral wall of the frontal diverges at about 20° from the midline and the orbital margin is shallowly concave in dorsal or ventral outline. UALVP 39989 ( Fig. 6D View FIG ) shows that the posterior edge of the frontal roof is nearly transverse and was sutured posteriorly in life with the paired parietals .

Frontals dorsally bear the typical albanerpetontid ornament of broad polygonal pits enclosed by low, narrow ridges. The pits are moderately deep on most specimens, but on several frontals the pits are so shallow they are difficult to see except under low-angled light ( Fig. 6C View FIG ). This variation occurs independent of frontal size, indicating it is not ontogenetic in origin. The well-preserved processes on UALVP 39983 argue against the indistinct dorsal ornament on this specimen being an artifact of weathering or abrasion.

In ventral view, the ventrolateral crest is broad – i.e. width of crest immediately behind slot for receipt of prefrontal is about 1.2 mm in UALVP 39987 ( Fig. 6E View FIG ) – but the crest is absolutely and relatively narrower than on comparable-sized frontals of A. inexpectatum (Gardner 1999d: pl. 2L). The crest is low and triangular in transverse view, being deepest medially and becoming shallower towards the lateral margin. The ventral surface faces ventrolaterally and is shallowly concave in the orbital region, again less so than in frontals of A. inexpectatum . As in other albanerpetontids, the posterior end of the ventrolateral crest extends past the posterior end of the frontals and would have underlapped the parietal in life.

REMARKS

Original publication for the name Albanerpeton nexuosus

Estes (1981) first published the name Albanerpeton nexuosus on page 24 of the Encyclopedia of Paleoherpetology, Part 2, where he provided an adequate account for the species, including the critical designation of the holotype. Yet in that account Estes (1981: 24) cited another 1981 paper (then in press) by himself, in National Geographic Society Research Reports, as the original publication for the name A. nexuosus (J.-C. Rage, pers. comm. 1999). However, because the latter paper was not published until the following year (Estes 1982) and no holotype was designated, Estes’ (1981) account in the Encyclopedia of Paleoherpetology remains the first valid publication for the name A. nexuosus .

Diagnostic features and affinities of Albanerpeton nexuosus

Estes (1981) and Rage & Hossini (2000) relied on four features to differentiate Albanerpeton nexuosus from other albanerpetontids. A closed notochordal pit in the atlas (Estes 1981) can be dismissed as a diagnostic character state because atlantes are not available for A. nexuosus . Among albanerpetontids as a whole, a closed notochordal pit is probably derived, but this condition is widespread and occurs in all known atlantal specimens (e.g., Estes & Hoffstetter 1976; Estes & Sanchíz 1982; Fox & Naylor 1982; McGowan 1996; McGowan & Ensom 1997; Gardner 1999a, b, d; this study), save for an indeterminate atlas (Seiffert 1969: fig. 1D) from the lower Bathonian of France. The claim that A. nexuosus differs from A. inexpectatum “in lacking a large palatal shelf [= pars palatinum, here] of the premaxilla and maxilla” (Estes 1981: 24; see also Rage & Hossini 2000) is difficult to evaluate because the four topotypic upper jaws Estes (1981) attributed to A. nexuosus are unavailable and his figures (Estes 1964: fig. 43a-d) do not depict these bones in an informative view. Estes (1981) may have misinterpreted the structure of these jaws, as he (Estes 1981: 20) did when he identified a similarly weak pars palatinum on an Albian premaxilla then referred to the salamander Prosiren elinorae Goin & Auffenberg, 1958 , but now designated as the holotype of A. arthridion (Fox & Naylor, 1982) . In fact, the pars palatinum on the Albian specimen is broken and largely missing (Fox & Naylor 1982; Gardner 1999a). Regardless, as I argued above, Estes’ (1981) four topotypic upper jaws cannot reliably be assigned to A. nexuosus . Upper jaws that I refer to A. nexuosus have a pars palatinum that is as well developed (i.e. lingually broad; palatine and maxillary process on premaxilla prominent) as in other albanerpetontid species. The third feature, lack of a dorsal process behind the dentary tooth row (Estes 1981; Rage & Hossini 2000), is not particularly diagnostic for A. nexuosus because the process is primitively absent in all albanerpetontids, except A. inexpectatum . The final feature, maxillary and dentary teeth strongly heterodont in size (Estes 1981; Rage & Hossini 2000), is indeed diagnostic for A. nexuosus and is discussed below.

Albanerpeton nexuosus is readily diagnosed by five autapomorphies of the jaws. The first three of these are unique among albanerpetontids to A. nexuosus , whereas the last two are unique within the genus: 1) boss on labial face of premaxilla covers about dorsal one-half of pars dorsalis (if present, boss primitively covers dorsal one-quarter to one-third of pars dorsalis); 2) premaxillary ornament consists of a regular arrangement of polygonal pits and ridges (ornament primitively consists of irregular pits, grooves, and ridges); 3) dorsal process on lingual edge of maxillary process on premaxilla a tall flange, continuous labiomedially with ridge that extends across dorsal face of pars palatinum to base of lateral internal strut (dorsal process primitively a low ridge and isolated from base of internal strut); 4) occlusal edge of pars dentalis on maxilla and dental parapet on dentary sinuous in labial outline, with apex strongly convex or angular and adjacent to longest teeth (margin primitively straight or shallowly convex); and 5) teeth on maxilla and dentary strongly heterodont in size, with longest teeth located about one-third of the distance from anterior end of tooth row and up to one-quarter again as long as nearby teeth (teeth primitively weakly heterodont in size).

Albanerpeton nexuosus is allied with A. inexpectatum and the unnamed Paleocene species in the robust-snouted clade by the following synapomorphies: premaxillae robust, variably fused, with pars dorsalis short and strongly sutured dorsally with nasal; premaxillary lateral process on maxilla short; and internasal process on frontals narrow and spike-like. In diagnosing a clade within Albanerpeton , these synapomorphies further support assigning A. nexuosus to the type genus. Elsewhere, I (Gardner 1999b, d) suggested that many of the synapomorphies of the robust-snouted clade strengthened the snout for burrowing, feeding, or some combination of these. Premaxillary autapomorphies of A. nexuosus probably further strengthened the snout for these activities. The most obvious explanation for the enlarged maxillary and dentary teeth in A. nexuosus is for subduing larger or more resilient prey. These enlarged teeth may also have been used to bite and injure opponents during intra- and interspecific fights, as has been documented for some extant salamanders (see review by Mathis et al. 1997), particularly plethodontids (e.g., Jaeger & Forester 1993; Staub 1993). The sinuous labial profiles of the occlusal edges of the maxilla and dentary in A. nexuosus are a direct consequence of the pars dentalis and dental parapet being deepest adjacent to the longest teeth, in order to adequately buttress these teeth labially.

Problematic reports of Albanerpeton nexuosus and mis-identified specimens

Estes (1981) assigned a topotypic femur (UCMP 55782) to Albanerpeton nexuosus largely because he could not attribute the specimen to any known Lancian caudate. Although UCMP 55782 is lost, Estes’ descriptions (1964, 1981) and figures (1964: fig. 44d, e) show that the specimen differs substantially from unequivocal albanerpetontid femora (cf. Estes & Hoffstetter 1976: pl. 9; fig. 5; McGowan & Evans 1995: fig. 1a, c) in being relatively shorter and more stout and in having the trochanter shorter and positioned more proximally. UCMP 55782 compares more favorably in these features with salamander femora (e.g., Francis 1934: pl. 5; figs 31-33) and should be regarded as such.

The identities of most of the non-topotypic jaws from the Lance, Hell Creek, Oldman, and Judith River formations that Estes (1981: 24) referred to A. nexuosus cannot be confirmed because he provided no figures, descriptions, or catalogue numbers for voucher specimens. Estes’ (1981: 24) references to specimens from Montana reported by Estes et al. (1969) and Sahni (1972) refer to, respectively, trunk vertebrae (MCZ 3652) of Prodesmodon from the Hell Creek Formation and indeterminate albanerpetontid dentaries (AMNH 8479 and 8480) from the type area of the Judith River Formation. Specimens available to me and listed here confirm that A. nexuosus occurs in the Lance, Hell Creek, and Oldman formations. Although I have not been able to establish the presence of A. nexuosus in the Judith River Formation, considering the widespread distribution of the species and that indeterminate albanerpetontid dentaries have already been collected from the formation, I predict the species will eventually be identified in the unit.

Breithaupt (1982: 133) referred a dozen jaws (UW 14582-14588, 14591, 14592 [incorrectly listed as UW 14542], 14593, 15030, 15031) from the Lance Formation (UW V-79032, Wyoming) to A. nexuosus . Just two of these can be referred to the species: an incomplete dentary (UW 14584) and maxilla (UW 14582; mis-identified as a dentary by Breithaupt [1982]). Of the remaining specimens, UW 14593 is a fragmentary premaxilla of A. galaktion, UW 15031 is the anterior end of a lizard dentary, and the other eight are fragmentary, indeterminate albanerpetontid jaws.

Standhardt (1986) reported A. nexuosus in the Aguja Formation of Texas on the strength of a fragmentary right maxilla (LSUMG V-1371) from LSUMG VL-113 and subsequently record- ed the species in a faunal list (Langston et al. 1989: 19) for the formation. Her figures (Standhardt 1986: fig. 29) confirm that LSUMG V-1371 is an albanerpetontid maxilla, but the specimen cannot be identified to genus or species.

Bryant (1989: 31) recorded A. nexuosus in the Hell Creek Formation based on two dentaries (UCMP 130683) from UCMP V-75162, in McCone County, Montana. Neither of the specimens in question is from an albanerpetontid: the first is an incomplete frog maxilla, whereas the second is an incomplete salamander dentary.

Most recently, Eaton et al. (1999: table 5) report- ed Albanerpeton sp. , cf. A. nexuosus in a faunal list for the Kaiparowits Formation, Utah. I cannot comment on this identification because no description or illustrations were provided and no voucher specimens were listed. Nevertheless, jaws reported here verify that albanerpetontids are abundant in the Kaiparowits Formation and that A. nexuosus , A. galaktion , and A. gracilis n. sp. are all represented.

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.

|

Kingdom |

|

|

Phylum |

|

|

Class |

|

|

Order |

|

|

Family |

|

|

Genus |

Albanerpeton nexuosus Estes, 1981

| Gardner, JD 2000 |

Albanerpeton

| Gardner 2000 |

Albanerpeton galaktion

| Fox & Naylor 1982: 121 - 127 |

Albanerpeton nexuosus

| Estes 1981: 24 |

A . nexuosus

| Estes 1981 |