Coffea arabica, L.

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.phytochem.2016.01.016 |

|

DOI |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.10515387 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/03F4281C-216E-FFEE-D87C-C904FB0683E0 |

|

treatment provided by |

Felipe |

|

scientific name |

Coffea arabica |

| status |

|

2.3. In vitro antioxidant capacity of C. arabica View in CoL and C. canephora

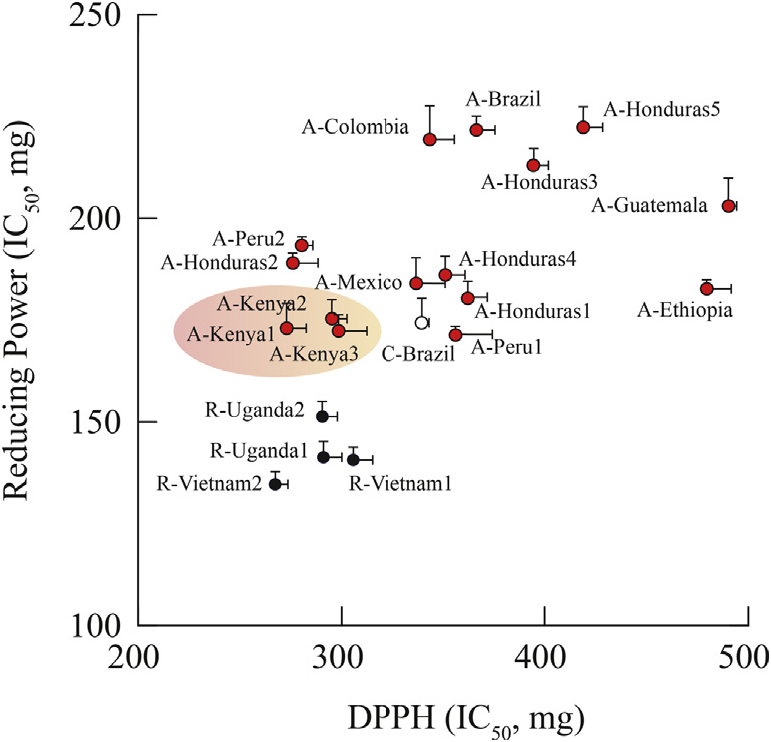

In order to assess the antioxidant capacity of the green coffee extracts, we evaluated their reducing power by ferric thiocyanate assay and the free radical scavenging activities by DPPH radical assay. In general, the extracts were more active as antioxidants when tested by the reducing power assay ( Fig. 5 View Fig ), since the steric accessibility of DPPH nitrogen-centered radical strongly affects the reaction rate of antioxidant compounds ( Prior et al., 2005). Fig. 5 View Fig depicts the scatter plot of IC 50 values from both tests. As expected, the four C. canephora accessions showed the highest antioxidant activity (lowest IC 50 values for both assays) with respect to all other accessions. Although weaker than chlorogenic acid ( Zhao et al., 2015), caffeine as well possesses antioxidant capacity, as recently demonstrated in in vivo experiments ( Tsoi et al., 2015). Therefore, the higher content of both chlorogenic acids and caffeine correlates with a higher antioxidant capacity.

Among the C. arabica accessions, the samples from Kenya showed the highest antioxidant capacity, followed by one of the accessions from Peru (A-Peru2) and one from Honduras (A-Honduras2). The lowest antioxidant capacity was observed in the Ethiopian (A-Ethiopia) and Guatemala (A-Guatemala) accessions, whereas intermediate antioxidant activities were observed for the remaining green coffee accessions.

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.

|

Kingdom |

|

|

Phylum |

|

|

Class |

|

|

Order |

|

|

Family |

|

|

Genus |