Zapus hudsonius (Zimmermann, 1780)

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6609503 |

|

DOI |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6609516 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/787F8798-2C04-FFBA-FA4E-AA4F972E60F8 |

|

treatment provided by |

Felipe |

|

scientific name |

Zapus hudsonius |

| status |

|

Meadow Jumping Mouse

French: Zapode des champs / German: Wiesenhipfmaus / Spanish: Raton saltador de pradera

Other common names: Hudson Bay Jumping Mouse

Taxonomy. Dipus hudsonius Zimmermann, 1780 ,

“Canada, Hudson Bay.” Restricted by R. M. Anderson in 1942 to Fort Severn , Ontario, Canada.

Asiazapus 1s the ancestor of Zapus and apparently originated in Asia in the late Pliocene and moved across the Bering Strait into northern North America. This was supported using ectoparasite analysis. Western North America was the area of dispersal of Zapus . It appears that Z. hudsonius was the earliest Zapus and occurred in Alaska. It probably gave rise to Z. trinotatus and Z. princeps . The three species of Zapus are quite closely related. Zapus hudsonius has been found in a late Pleistocene cave deposit in Robinson Cave, Overton County, Tennessee. Two extinct subspecies are known only from the Pleistocene in Kansas: adamsi named by C. W. Hibbard in 1955 from Meade Co., late Sangamon interglacial, and transitionalis named by D. Klingener in 1963 from Big Springs Ranch, Meade Co., late Illinoian. Several workers have questioned validity of the subspecies preblei. Twelve subspecies recognized.

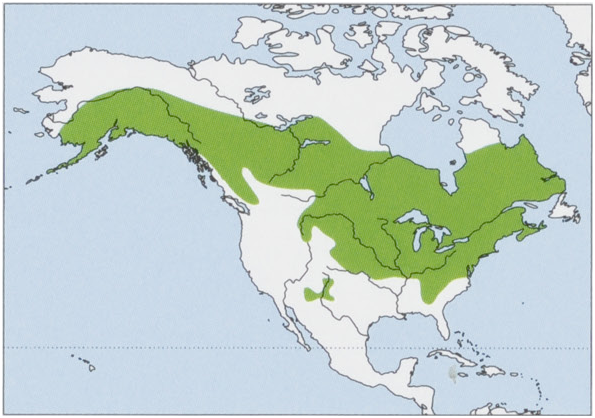

Subspecies and Distribution.

Z.h.alascensisMerriam,1897—SWAlaska.

Z.h.americanusBarton,1799—EUSA(Indiana,Ohio,andSWNewYork,StoNEAlabama,NWGeorgia,andNWSouthCarolina).

Z.h.campestrisPreble,1899—NCUSA(whereMontana,SouthDakota,andWyomingmeet).

Z.h.canadensisDavies,1798—SECanada(EOntarioandWQuebec).

Z.h.ladasBangs,1899—ECanada(LabradorandNEQuebec).

Z.h.luteusG.S.Miller,1911—SCUSA(CNewMexicoandECArizona).

Z.h.preblerKrutzsch,1954—CUSA(SEWyomingandNCColorado).

Z. h. tenellus Merriam, 1897 — SW Canada (S British Columbia). View Figure

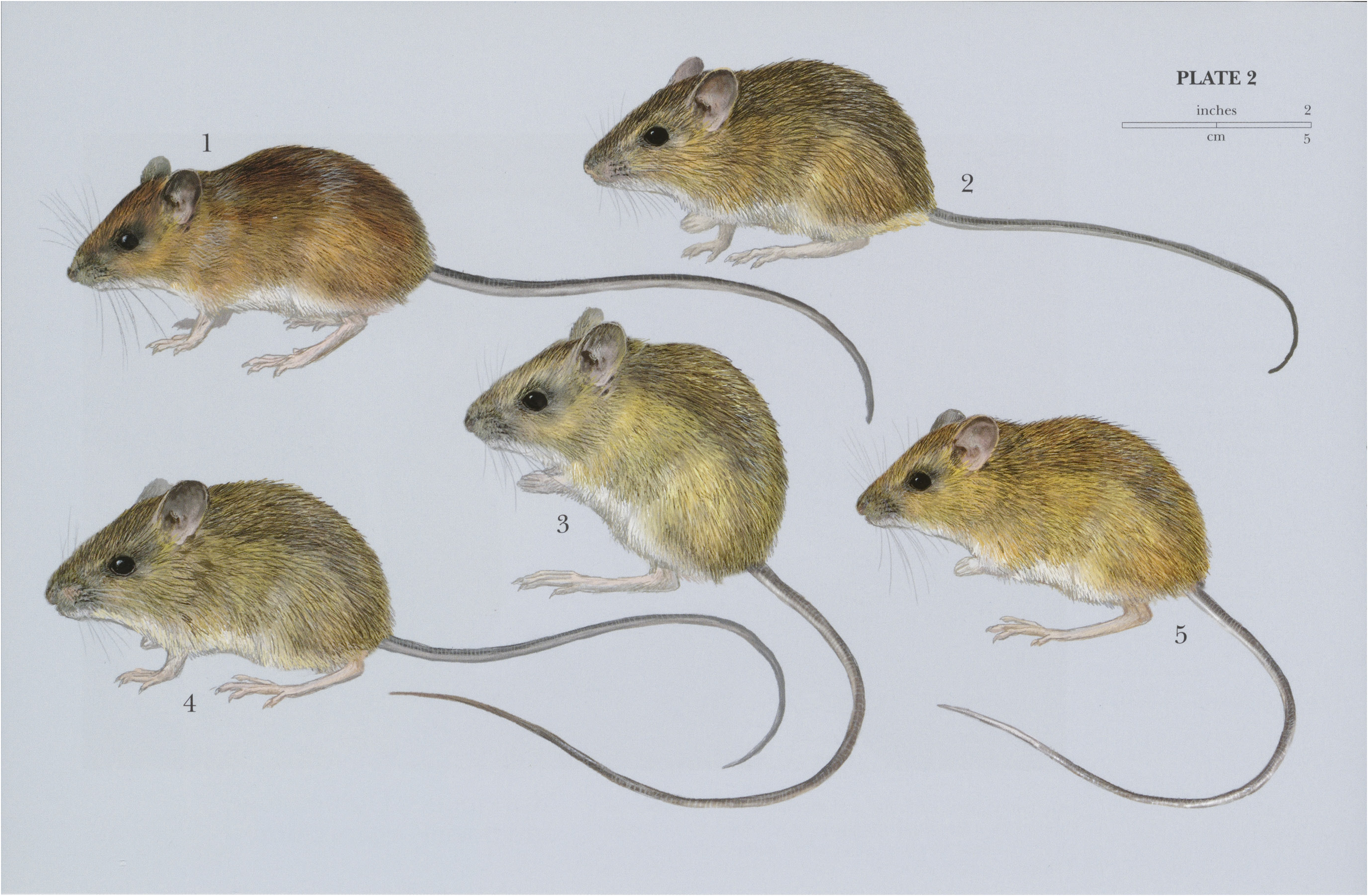

Descriptive notes. Head-body 75-92 mm, tail 108-155 mm, hindfoot 28-35 mm; weight 13-5-26-5 g. The Meadow Jumping Mouse is medium-sized, with an exceedingly long tail, longer than head-body length. Hindlegs and feet are enlarged, making long jumps possible. It is the smallest and lightest colored species of Zapus . Sides are yellowish and interspersed with dark guard hairs. Darker longitudinal band runs down back. Underparts are typically white but sometimes have yellowish or ocherous tinge. Tail is dark on top and light below. Overall size of femalesis slightly larger than males. Infraorbital foramen is large and oval. Zygomatic plate is nearly horizontal rather than oblique and is narrower than, and completely beneath, infraorbital foramen. Nasal bones project considerably beyond incisors. Incisive foramina of rostrum are short. Incisors are orange or yellow, and upper incisors have deep grooves on anterior surfaces. There are four upper molariform teeth, and first premolar is much smaller than in other species of Zapus ; toothrow is usually less than 3-7 mm. The Meadow Jumping Mouse has the smallest first molariform tooth, measuring 0-30 mm x 0-35 mm, compared with the other two species of Zapus . Molars are rooted and flat-crowned and have a complicated pattern of re-entrant folds,islands, and valleys. Dental formula is I 1/1,C0/0,PM 1/0,M 3/3 (x2) = 18.

Habitat. Mostly dry or wet abandoned fields, brushy areas, and also woods when ground cover is adequate, but especially where the Woodland Jumping Mouse ( Napaeozapus insignis ) is absent. At Ithaca, Tompkins Co., New York, Meadow Jumping Mice were found most commonly in open fields, but densities were higher in marshy areas and along ponds. Many were also found in brush and brushy fields. Highest numbers were found in good and fair cover, and distance from water and soil moisture seemed to be oflittle importance. In the south-eastern Yukon, the Meadow Jumping Mouse constituted 19-7% of captures in forest interior, forest edge, and logged forest. In northern Indiana, they did not associate more frequently with grassland habitat than forested areas.

Food and Feeding. Meadow Jumping Mice mainly eat seeds but also berries and other fruits, nuts, and insects. Percent volume of seeds in diets of 796 individuals from Tompkins Co., New York,steadily increased from 0% in April to 73-1% in October; percent volume of animal materials, mostly insects, decreased from 35-4% in April to 11-7% in October; and percent volume of fungi, mostly Endogonaceae , was 0% in April and peaked at 21-4% in August. The subspecies luteus in New Mexico fed on common threesquare ( Schoenoplectus , Cyperaceae ), spikerush ( Eleocharis , Cyperaceae ), saltgrass ( Distichlis , Poaceae ), foxtail barley ( Hordeum , Poaceae ), wild rye ( Elymus , Poaceae ), brome ( Bromus , Poaceae ), and wheatgrass ( Triticum , Poaceae ). MeadowJumping Mice frequently foraged in the canopy of herbaceous vegetation. Many kinds of seeds are eaten, varying seasonally with availability. From Tompkins Co., New York, some of the more important seeds were from milkweed ( Asclepias , Apocynaceae ), elm ( Ulmus , Ulmaceae ), touch-me-not (/mpatiens, Balsaminaceae ), rush ( Juncaceae ), chickweed (Stellara, Caryophyllaceae ), dock ( Rumex , Polygonaceae ), cinquefoil ( Potentilla , Rosaceae ), wood sorrel ( Oxalis , Oxalidaceae ), and grasses ( Poaceae ), including sweet vernal grass ( Anthoxanthum ), bluegrass ( Poa ), orchard grass ( Dactylis ), timothy grass ( Phleum ), quack grass ( Elymus ), poverty grass ( Aristida ), rice cut grass ( Leersia ), and barnyard grass ( Echinochloa ). Fruits of strawberry ( Fragaria , Rosaceae ), blackberry ( Rubus , Rosaceae ), blueberry ( Vaccinium , Ericaceae ), and viburnum ( Adoxaceae ) were eaten in season, and flowers of red maple ( Acer rubrum, Sapindaceae ) and clover ( Trifolium , Fabaceae ) were sometimes eaten. Major animal foods were caterpillars, beetles, spiders, sowbugs, and moths. Fungi comprised ¢.8-20% of the diet in July-September. Fungi ingested consisted mostly of a tiny subterranean fungus of the family Endogonaceae . It was clear from the high incidence in stomachs (often 50-100% volume) that this fungus was actively sought and not just taken incidentally. Meadow Jumping Mice will reach up stems of some grasses, cut them off as high as they can reach, and pull them down until seed heads are reached. Stems are left in neatpiles on the ground, with rachis on top of piles. In central New York, this most often consisted of timothy grass. Foods in Indiana were similar to those in New York, with touch-me-not being the most common food item and the fungi Endogone and Hymenogaster (Agaricomycetes) forming 17-4% of diets by volume. Energy values of Endogone in Indiana were 2735 calories/g. For comparison, measurements of six kinds of seeds studied by S. C. Kendeigh and G. C. West in 1965 ranged from 4317 calories/g to 5625 calories/g. Some predators include barn owls (7yto alba), great horned owls (Bubo virginianus), northern long-eared owls (Asio otus), screech owls (Megascops), hen harriers (Circus cyaneus), red-tailed hawks (Buteo jamaicensis), Coyotes (Canis latrans), domestic cats, Red Foxes (Vulpes vulpes), Northern Gray Foxes (Urocyon cinereoargenteus), American Minks (Neovison vison), weasels (Mustela), milksnakes (Lampropeltis), rattlesnakes (Crotalinae), water moccasins (Agkistrodon piscivorus), green frogs, and northern pikes (Esox lucius). Owls, especially barn owls, seem to be prevalent predators of the Meadow Jumping Mouse. In a study by J. O. Whitaker, Jr. in Tompkins County, New York in the 1960s, a large rod-shaped anaerobic bacteria, Bacteroides sp., was found in all of ¢.60 intestinal tracts. Bacteroides in the gut was scarce in spring but very abundant in late summer and autumn. A number of internal parasites have been observed in Meadow Jumping Mice. Two species of flagellates (Hexamita) were found in all individuals examined from Tompkins Co., and seven of 23 individuals yielded Eimeria (Coccidia). Trematodes (flukes) include Echinostoma sp., Plagiorchis proximus, Notocotylus (Quinqueserialis) hassali, Quinquerialis quinqueserialis, Schistosomatium douthitti. Cestodes (Tapeworms) include Choanotaenia sp., Hymenolepsis sp., Mesocestoides sp., and Taenia mustelae (larvae). Nematodes (roundworms) include Citellinoides zapodis, Longistriata dalrymplei, Mastophoris muris, Notocotylus hassalli, Rictularia sp., Spirocerca zapi, and Subulura ungulatus. Many different external parasites are found on Meadow Jumping Mice. Mites include species of Glycyphagidae : Glycyphagus newyorkensis, G. hypudaei, G. zapus, Orycteroxenus soricis, and Xenoryctes latiporus. Of 579 individuals examined by Whitaker, 334 contained numerous individuals of “Dermacarus” sp. ( Glycyphagidae ) later found to include Glycyphagus newyorkensis and G. hypudaei. These are hypopial (transport) stages, often found in great numbers on small mammals: Laelapidae, Androlaelaps fahrenholzi, Echinonyssus isabellinus, Haemogamasus ambulans, H. liponyssoides, H. reidi, and Laelaps kochi; Listrophoridae, Listrophorus mexicanus, Macrochelidae , M. mesochthonius; Macronyssidae, Ornithonyssus bacoti; Myobiidae, Radfordia ewingi; and Pygmephoridae, Pygmephorus mahunkai and P. spinosus. Chiggers (Leewenhorkiidae, Trombiculidae ) included Euschoengastia dwersa, E. peromysci, E. rubra, E. setosa, Eutrombicula alfreddugest, E. splendens, Leptotrombidtum peromysci, Neoschoengastia sp., Neotrombicula harperi, N. lipouskyi, N. microti, N. sylvilagn, N. whartoni, Trombicula browni, and T. subsignata. Ticks ( Ixodidae ) included Dermacentor vanriabilis and Ixodes muris. Fleas (Siphonaptera) reported include Corrodopsylla curvata, Clenopthalmis pseudagyrtes, Megabothris asio, M. quirini, M. wagneri, Ochopeas leucopus, and Stenoponia americana. Botflies (Cuterebra) and sucking lice, although not characteristic, have been found on MeadowJumping Mice.

Breeding. Male MeadowJumping Mice emerge before females, and mating takes place soon after females emerge. In the first week of May, 40% of males were scrotal, and by the second week, all were scrotal. Gestation is 17-21 days, with longer periods for lactating individuals. There are three peaks of production of young in Minnesota and New York: late June, midand late July, and mid-August. Litters are produced throughout the warm period, but few in May and September. Greatest numbers oflitters were produced in the first three weeks in June and the first three weeks in August. Many females have two litters, one in June and one in August. It is unlikely, but possible, that a few females have three litters. High proportions of juveniles were in a population in mid-July and late August in Michigan, lagging behind peak production of young. Average numbers of young perlitter were 5-7 in Minnesota and 4-5 in New York. Mean number of young per litter from the literature plus 78 individuals from Tompkins Co., New York, was 5-5 (range 2-9). Newborn young are naked and produce a high squeaking noise that can be heard for about 1 m feet. During their first week, young can crawl but not stand. External auditory meatus opens, and they can react to sound about day 20. Eyes open about day 25, and young begin to emerge from nests and eat solid food. Suckling may continue for a time after this, but by the end of week four, young are fully furred and can fend for themselves. Nests are generally underground, often at a depth of ¢.15 cm. Nests have also been found in grassy hummocks, in open fields, under planks and other objects, and in hollow logs; one nest was found in the base of a living oak tree.

Activity patterns. Although called jumping mice, Meadow Jumping Mice usually walk or crawl through the grass. When alarmed or chased and needing to travel more quickly, they can hop distances of c.1 m. They can stop abruptly and remain motionless under vegetation, and they are then hard to find. They are docile and seldom attempt to bite; they are not antagonistic toward each other. They often wash their faces, feet, and tails. Long tail is passed all the way through the mouth when washing. Most activity occurs at night. Trapping in New York for two five-day periods, with traps being checked at dawn, noon, and dusk, yielded 31 individuals: 27 at night, two at dusk, and one each in morning and afternoon. The Meadow Jumping Mouse is one of the most profound hibernators, remaining in this condition for c¢.6 months. In preparation for hibernation, individuals accumulate large amounts of fat (c.6 g). This weight gain occurs over c.2 weeks per individual; however, not all mice put on fat at the same time. Hibernation begins in some individuals about 1 September, and as shown by last dates of capture, it would appear that nearly all individuals are hibernating by mid-October. If it is assumed thatfat increase takes c.2 weeks and that individuals enter hibernation right after attaining fat, then nearly all individuals will have entered hibernation in c.6 weeks. Sufficient energy from fat must be available to maintain individuals until spring emergence or they will die during hibernation. Early dates of emergence in New York were between 25 April and 6 May. In autumn, late dates were 11 October to 1 November. Most individuals entered hibernation between 1 September and 15 October—young later than adults. Fewjumping mice were captured before 30 April (6 in 19,457 trap nights) and after 20 October (3 in 16,028 trap nights). MeadowJumping Mice were active in central New York primarily from 1 May through 20 October. In Michigan, emergence dates in three different years were 20 and 26 April and 3 May for males and 5, 9, and 17 May for females. Near Toronto (Ontario, Canada), males usually entered hibernation about 20 August and females from mid-September through mid-October. Old males were the first to hibernate, followed by old females, then young males, and finally young females. More males (39%) than females (18%) survived hibernation, but this difference was not significant. Two males and four females survived three winters and thus were three years old. Males on average are heavier than females, and weight loss averaged 36-8% in males and 34-5% in females. Hibernacula have been found along banks, in piles of dirt, and at least one in a pile of ashes. On 22 January 1974, a nest was found that contained a hibernating Meadow Jumping Mouse. It was an adult female and was in a dike along the Wabash River in Vigo County, Indiana. The nest was c.14 cm in diameter and composed entirely of leaves of fescue grass, the main plant on the dike. Its stomach and small intestine were nearly empty; cecum contained fine material in the distal fifth; and large intestine contained nine pellets with highly digested pieces of grass seeds, vegetation, and fungal spores. Eight mites Androlaelapsfahrenholzi ( Laelapidae ) were found on the female, and a number of insects and other invertebrates were found in the nest including 26 springtails of two species, two pauropods, and eleven nematodes.

Movements, Home range and Social organization. In Minnesota, home ranges were 769-3521 m? (mean 1538 m?) for females and 566-4452 m? (mean 1740 m?) for males. In another area in Minnesota, nine male home ranges averaged 10,927 m?, and 17 female home ranges averaged 6475 m*. Average home ranges in Michigan were 3602 m? for 26 males and 3723 m? for 24 females. Density was 48-3 ind/ha in one Minnesota study area, and it ranged from 7-4 ind/ha to 14-4 ind/ha in another study. Densities of 4-4-18-5 ind/ha were found in eastern Massachusetts. Other small mammal associates of the Meadow Jumping Mouse reported from New York and Toronto were the Northern Short-tailed Shrews ( Blarina brevicauda ), Cinereus Shrews (Sorex cinereus), Star-nosed Moles (Condylura cristata), White-footed Deermice ( Peromyscus leucopus), Meadow Voles ( Microtus pennsylvanicus), and House Mice (Mus musculus).

Status and Conservation. Classified as Least Concern on The IUCN Red List. The MeadowJumping Mouse is widely distributed, common and not in decline throughout most of its extensive distribution, and occurs in many protected areas. Population trends are stable, and it is unlikely to be declining fast enough to qualify for listing in a more threatened category. It is classified as “critically rare with habitat decreasing” in South Dakota and is listed as threatened in New Mexico. Subspecies preblei is listed as Priority 2 in Wyoming and as a non-game species with legal protection in Colorado.

Bibliography. Adler et al. (1984), Allred & Beck (1966), Anderson (1942), Bailey (1926), Blair (1940a), Brennan & Beck (1955), Brennan & Wharton (1950), Connor (1960, 1966, 1971), Dearborn (1932), Dodds et al. (1969), Drummond (1957), Easton & Wrenn (1988), Erickson (1938), Errington et al. (1940), Fain & Whitaker (1973, 1974), Fain et al. (1985), Farrell (1956), Fisher (1893, 1896), Fox (1940), Freeman (1956), Geary (1959), Goodwin (1924, 1929), Grimm & Whitebread (1952), Guilday (1949), Hafner et al. (1981), Hamerstrom & Mattson (1939), Hamilton (1935), Hibbard (1955), Holland & Benton (1968), Hoyle & Boonstra (1986), Jones & Thomas (1982), Jones & Whitaker (1976), Jung & Powell (2011), Kardos (1954), Kendeigh & West (1965), Klingener (1963), Krantz & Whitaker (1988), Krutzsch (1954), Latham (1950), Lawrence et al. (1965), Lichtenfels & Haley (1968), Loomis (1956), Lubinsky (1957), Martell et al. (1969), McIntosh & Mcintosh (1934), Muchlinski (1988), Murie (1945), Nichols & Nichols (1935), Quimby (1951), Ramey et al. (2005), Randall (1939, 1940), Richards & Hine (1953), Richmond & Roslund (1949), Ritzi & Whitaker (2003), Roslund (1951), Rupes & Whitaker (1968), Schad (1954), Schueler (1951), Seton (1909), Sheldon (1938), Stupka (1931), Surface (1906), Timm (1975), Townsend (1935), Trainor et al. (2012), Urban & Swihart (2009), Vergeer (1948), Whitaker (1962, 1963a, 1963b, 1972, 1979, 1982, 1991), Whitaker & French (1982), Whitaker & Hamilton (1998), Whitaker & Loomis (1978), Whitaker & Mumford (1970), Whitaker et al. (1975), Wilson (1938), Wrenn (1974), Wright, B. (1979), Wright, G.D. & Frey (2014).

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.