Strieremaeus, , Sellnick, 1918

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/10.11646/zootaxa.2993.1.3 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/E067450A-204D-F457-FF20-FA79C079F955 |

|

treatment provided by |

Felipe |

|

scientific name |

Strieremaeus |

| status |

|

Comparison of Strieremaeus and Archaeorchestes

Archeorchestes is a monobasic genus of oribatid mites from Lower Cretaceous amber of Àlava ( Spain); at an estimated 113 my ( Alonso et al. 2000), this amber is nearly three times older than Baltic amber. The type species—— A. minguezae Arillo & Subías, 2000 ——was described based on a single adult specimen. Arillo & Subías (2000) proposed the family Archaeorchestidae to accomodate this mite and considered it the sister family of Zetorchestidae .

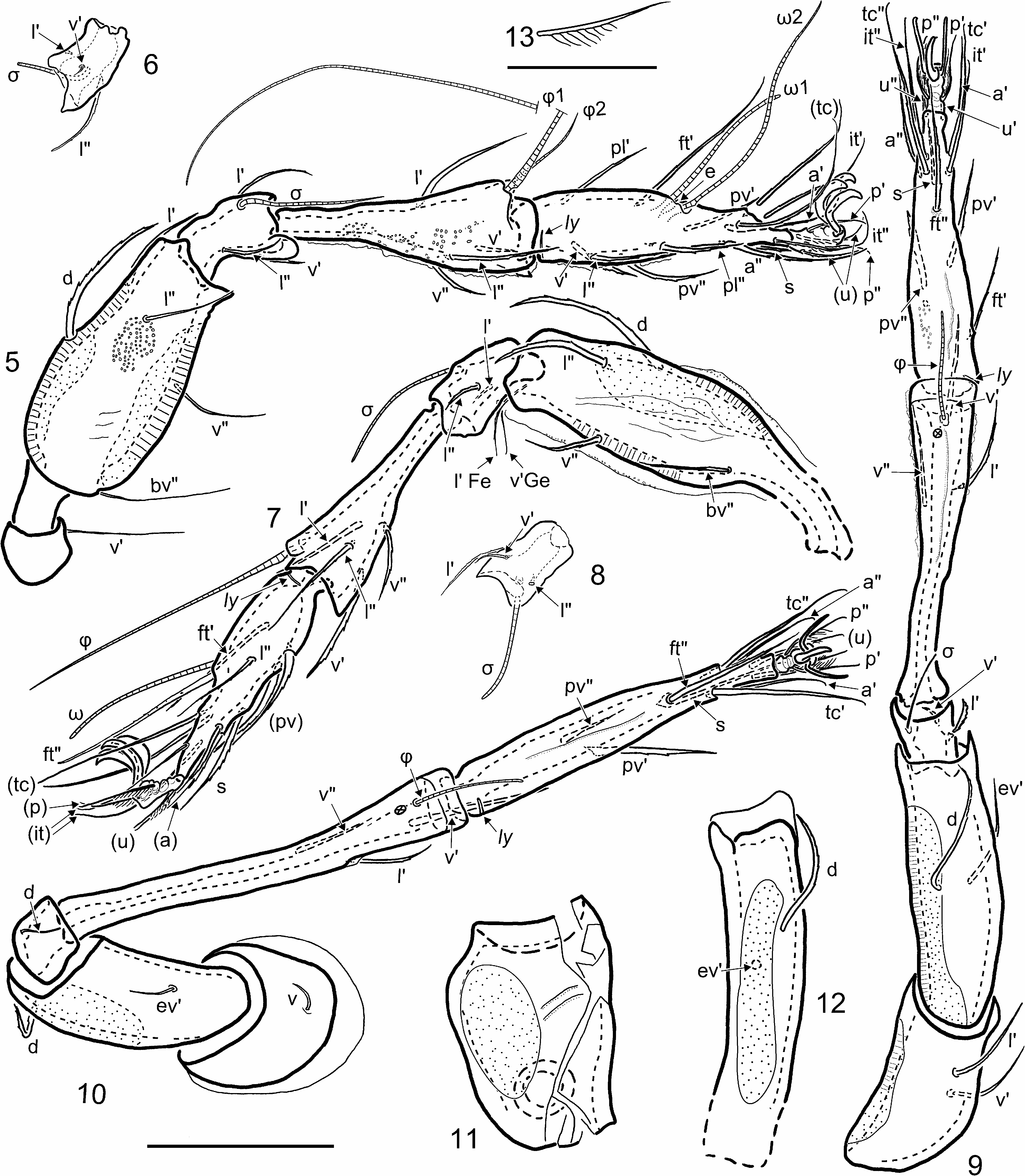

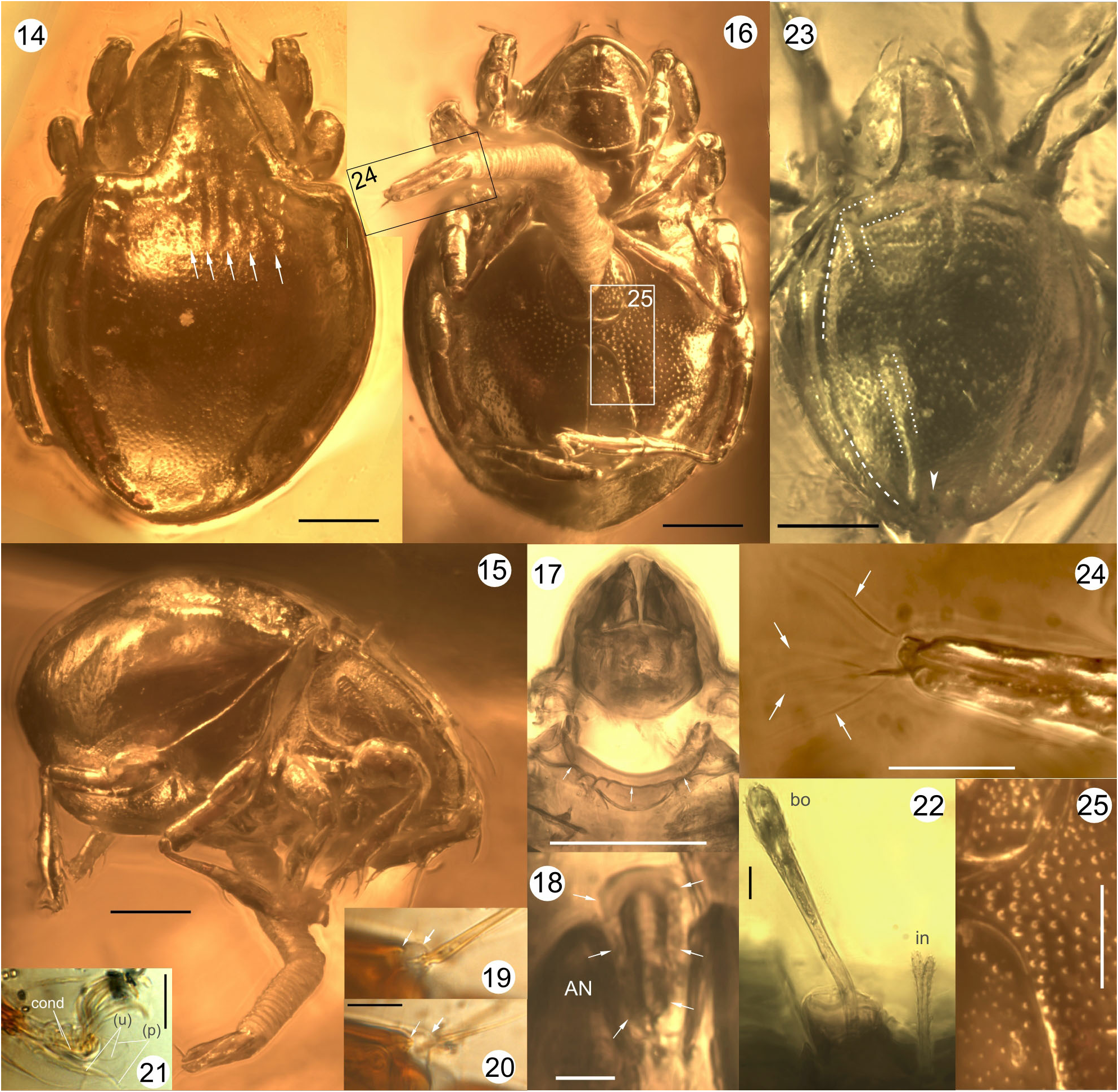

Arillo & Subías (2000) did not refer to Sellnick’s amber studies, but their dorsal image of A. minguezae (their Fig. 1 View FIGURES 1–4 ) resembles that of S. illibatus ( Sellnick 1918; his Fig. 8 View FIGURES 5–13 ) in: general shape and proportions, the nature of prodorsal ridges and setae, the form of pedotecta, and the parallel grooves at the anterior margin of the notogaster. Comparing Sellnick’s text it seems they have similar foveolate cuticle and a similar anogenital region. Following our studies of S. illibatus it became clear that this resemblance is not superficial (cf. Fig. 1 View FIGURES 1–4 of Arillo & Subías with our Figs. 14 and 23 View FIGURES 14–25 ) and that the mites are close relatives. While the single published measurements are quite different (length of 400 µm for A. minguezae , 565 µm for S. illibatus ), our specimens of S. illibatus ranged widely (427–599 µm), reflecting the probability that we studied both males and females. Such resemblance led us to examine the holotype of A. minguezae . While the nature of its preservation does not allow full comparison with S. illibatus —particularly regarding characters that are in obscured regions—it revealed more extensive and detailed similarities.

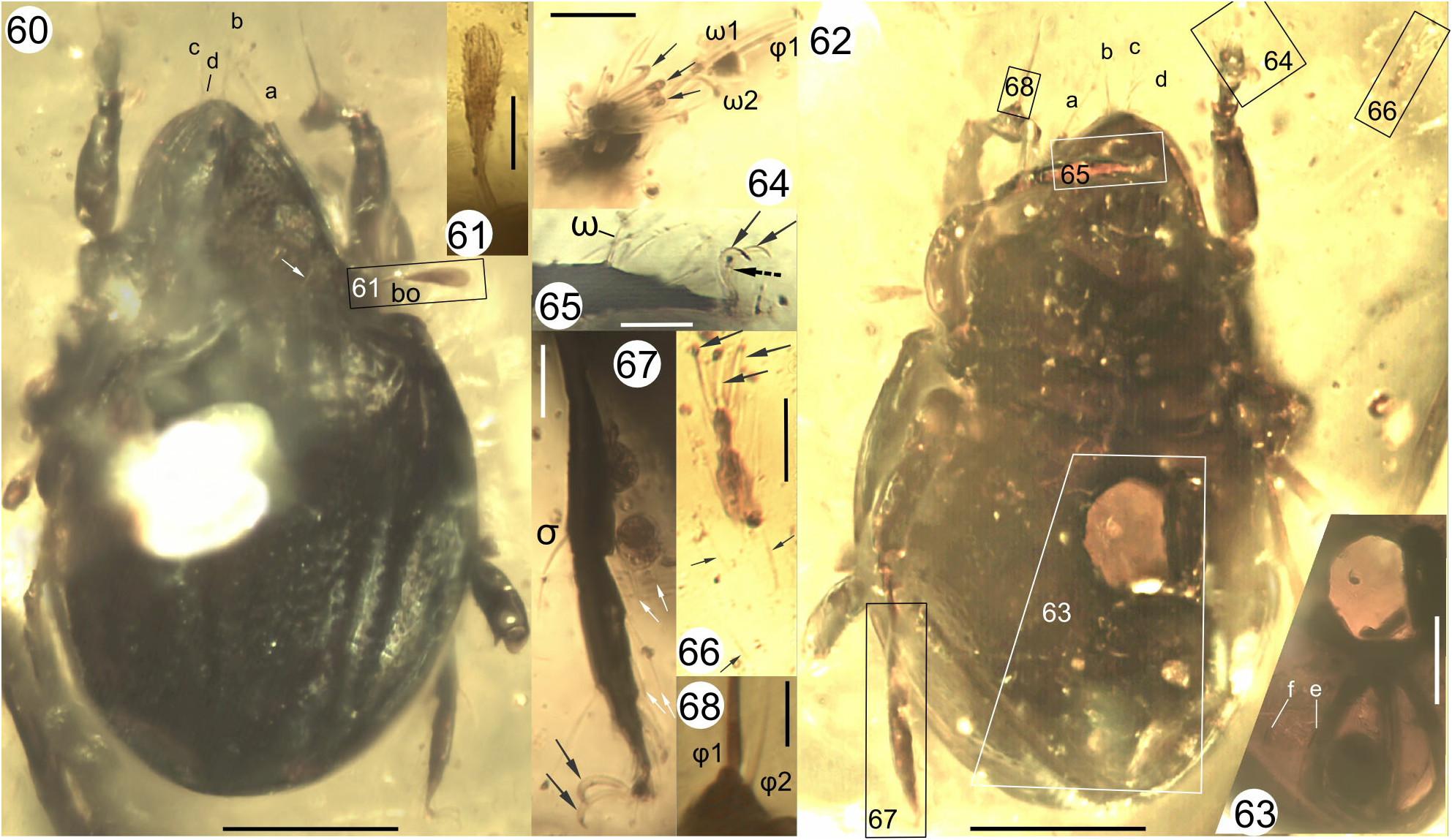

The prodorsal structure of the holotype is virtually identical to that of S. illibatus , but in the interpretation of Arillo & Subías there is one notable difference: they characterized the rostral setae ( ro) as being close together in a central (medial) position. However, the prodorsal setation is difficult to resolve in the holotype and we feel this difference is an artifact. There are four visible anterior setae ( a, b, c, d on Figs. 60, 62 View FIGURES 60–68 ). One of these ( d) is broken from its alveolus and displaced to under the rostrum. The bases of two other setae ( b, c) are not visible with confidence, so the only unequivocal setal identification is a, which is the right seta le, inserted on the small, blunt distal cusp of the lamella. Seta d may be the left seta le, displaced from its original position, while b and c may be rostral setae, as the authors suggested. However, d alternatively may be displaced seta ro, or it could come from leg II or even from the palp. As seta b is well aligned with the left lamella, it may be the left le; in this case, the only discernible preserved seta ro would be c, and its position is quite normal—anteroventral to and slightly lateral to the end of the lamella—just as in S. illibatus . While the forked seta in is an important diagnostic feature of S. illibatus , it remains unknown in A. minguezae . Neither the setae themselves nor even their alveolae could be discerned in the mist of small bubbles that covers the posterior part of the prodorsum, but a white arrow on Fig. 60 View FIGURES 60–68 points to a vague rod-like structure in this region. The right seta bo is well preserved in the holotype; its narrowly-clavate head has small spicules arranged in longitudinal rows ( Figs. 60, 61 View FIGURES 60–68 ). In S. illibatus the appearance of bo can vary—the head has spicules all over its surface in some specimens, but in others the central part appears smooth—so no differences can be identified.

The notogaster of A. minguezae is nearly identical with that of S. illibatus . The surface topography of the holotype seems slightly more accentuated than in S. illibatus , particularly the chevron-like humeral angle, but the consistency and importance of this is unknown.

As well as could be determined, ventral structures are also similar. The dark bands that Arillo & Subías (2000; their Fig. 1 View FIGURES 1–4 ) noted around anal and genital plates and around epimeres of A. minguezae can be seen in some S. illibatus specimens but not in others, and the difference seems related to preservation. The position on the ventral plate of adanal lyrifissure iad may differ between the two species. Closely lateral to the anal plates of A. minguezae there is a linear structure ( e on Fig. 63 View FIGURES 60–68 ) that the original authors interpreted as iad, but it is impossible to discern the internal canal that these structures possess. Another lyrifissure-like structure ( f on Fig. 63 View FIGURES 60–68 ) is located more laterally, in the position of iad in S. illibatus , but again no canal is discernible. The right side of the holotype shows nothing in either of these positions, due to unfavorable orientation and a large bubble near the anal opening, so the position of iad in A.minguezae remains unresolved.

Legs are also very similar. In the original description, left leg II of the A. minguezae holotype is said to be not preserved. In fact it is partially discernible, but only the distal part of the tarsus retains cuticle ( Figs. 62, 66 View FIGURES 60–68 ). More proximal cuticle was destroyed during preservation, but its course is partially indicated by three preserved setae that seem to have retained their original positions, proximally on the tarsus and distally on the tibia ( Fig. 66 View FIGURES 60–68 , small arrows). There is some potential for a difference in the number of tarsal claws: each tarsus of S. illibatus is clearly tridactylous, but Arillo & Subías (2000) considered A. minguezae to have a condition that would be unique among oribatid mites: tarsus I tridactylous but tarsi II–IV bidactylous. This apparent difference may be an artifact of preservation. The distal fragment of left tarsus II clearly displays three claws ( Fig. 66 View FIGURES 60–68 , large arrows), but on right tarsus II only two claws are fully visible; the latter also shows a shadow that could represent dissolved cuticle of the third claw (dotted arrow on Fig. 64 View FIGURES 60–68 ). No trace of the third claw is visible on right tarsus III, nor on (poorly observable) left legs III and IV. However, it is clear that cuticle can be lost during preservation, so we view the apparent difference as equivocal.

Distal parts of left leg I, right leg II and right leg III are well preserved in A. minguezae , so that some detailed traits could be observed, and all proved to be identical to those in S. illibatus . Each visible tarsus in A. minguezae has a hyaline ambulacral stalk distal to setae ( u). Setae ( p) and claws are inserted on the widened distal part of this stalk. The discernable setation of tarsus I (partly visible in Fig. 64 View FIGURES 60–68 ) includes ( p), ( u), ( it), ( tc), ft', ( pl), l", ( a), s, ( pv), and two long solenidia of which the anterior is rather stiff and the posterior curved anteriorly, so that they intersect; seta ft” is absent. Tibia I has two solenidia, of which the larger φ 1 is thickened near the base, consistent with being keel-shaped ( Fig. 68 View FIGURES 60–68 ) and inserted on a large apophysis; the smaller φ 2 is inserted on a small triangular apophysis (only the tip of which is visible in the image). The distribution of visible setiform organs on right tarsus II of A. minguezae is identical to that in S. illibatus (cf. Figs. 7 View FIGURES 5–13 and 67 View FIGURES 60–68 ), including the absence of a second solenidion. On tarsus III setae ( p), ( u), ( it), ( tc), ( a), s and ( pv) were discerned and one seta in a dorsal position (probably ft") is inserted about midlength on tarsus, as in S. illibatus . On tibia III, one curved thin solenidion and two setae on the ventral face, well aligned with tarsal ( pv), are visible (arrows on Fig. 65 View FIGURES 60–68 ); these seem homologous with v” and l’ of S. illibatus .

It is clear that, despite about 70 million years difference in age, S. illibatus and A. minguezae differ little and we hereby consider Archaeorchestes to be a junior subjective synonym of Strieremaeus ( n. syn.). The Spanish amber species is recombined as Strieremaeus minguezae ( Arillo & Subías, 2000) n. comb. At this time, the only objective morphological distinction between these species is size; at a length of 400 µm the holotype of S. minguezae is smaller than the known range for S. illibatus (427–599 µm). The possibly more accentuated notogastral sculpturing is difficult to characterize; it can seem to vary with lighting and probably varies among specimens and with the nature of preservation. If further samples of S. minguezae are discovered the possible differences in these characters—as well as in the equivocal differences in tarsal claws, rostral seta position and insertion of lyrifissure iad — can be reexamined, and leg setation can be compared in full. If all prove similar, synonymy of the names should be considered.

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.