Automate awaji, Komai & Tamego & Hanano, 2020

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/ 10.11646/zootaxa.4820.2.5 |

|

publication LSID |

lsid:zoobank.org:pub:8FEA367B-20B7-42FC-B014-F3DA488D3C6C |

|

DOI |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.4397951 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/7E87BCFE-A1D5-4EA7-9C8C-22D7FCF245DB |

|

taxon LSID |

lsid:zoobank.org:act:7E87BCFE-A1D5-4EA7-9C8C-22D7FCF245DB |

|

treatment provided by |

Plazi |

|

scientific name |

Automate awaji |

| status |

sp. nov. |

Automate awaji n. sp.

[New Japanese name: Awaji-otohime-teppou-ebi]

Figs. 1–6 View FIGURE 1 View FIGURE 2 View FIGURE 3 View FIGURE 4 View FIGURE 5 View FIGURE 6

Material examined. Holotype: female (cl 7.4 mm), Yura , Awaji Island, Kitan Strait, Japan, 34.3005N 134.9405E to 34.3001N 134.9416E, 4–8 m, airlift suction sampler, coll. T. Tamego & K. Hanano, 10 March 2018, CBM-ZC 16005. GoogleMaps

Paratypes: 3 specimens (sex not determined), same collection data as holotype, CBM-ZC 16006 (cl 5.0 mm), CBM-ZC 16007 (cl 5.2 mm), CBM-ZC 16008 (cl 5.3 mm, with both chelipeds) GoogleMaps .

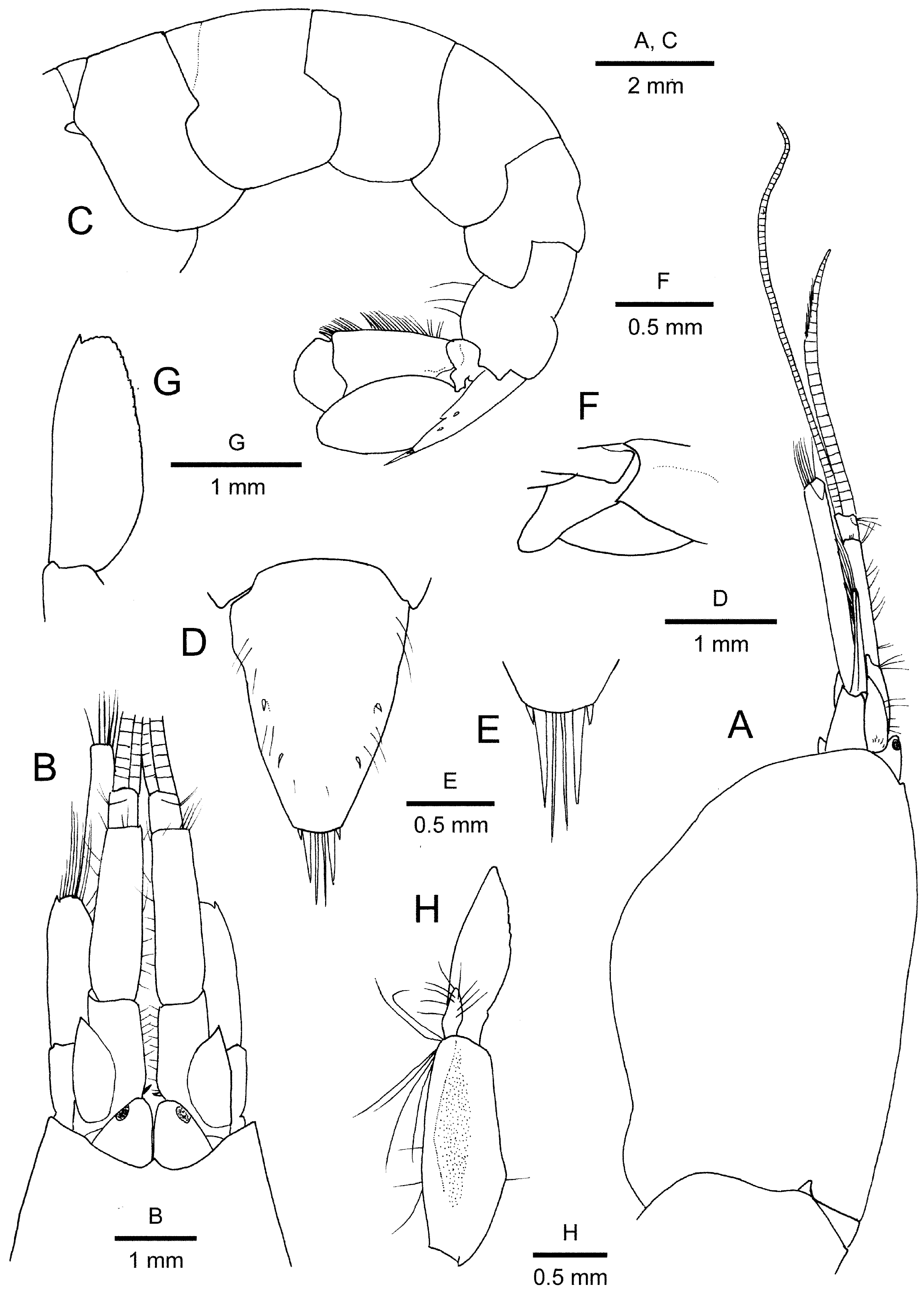

Description of holotype. Carapace ( Figs. 1A, B View FIGURE 1 , 3A, B View FIGURE 3 ) glabrous, somewhat compressed laterally; frontal margin generally concave; rostrum very small, broadly triangular, with sharply pointed apex; rostral carina and orbital teeth absent; dorsum slightly sloping anteriorly; anterolateral to pterygostomial margins broadly rounded, continuous with branchiostegal margin; branchiostegal ventral margin with shallow notch corresponding to base of pereopod 4; cardiac notch conspicuous.

Pleon ( Figs. 1A View FIGURE 1 , 3C View FIGURE 3 ) with pleura 1–5 rounded ventrally; pleomere 6 without posteroventral articulated flap, posterolateral projection truncate; preanal plate posteriorly rounded. Telson ( Fig. 3D, E View FIGURE 3 ) subtrapezoidal, broad at base, strongly tapering to narrow truncate posterior margin, with 2 pairs of dorsolateral spiniform setae, first and second pair situated at about mid-length and posterior three-quarters of telson length, respectively; lateral margins faintly constricted at about anterior one-third; posterior margin with 2 pairs of spiniform setae at each lateral angle (mesial setae exceeding 5 times length of lateral) and between them 1 pair of stiff setae, latter longer than mesial pair of spiniform setae.

Eyestalks ( Fig. 3A, B View FIGURE 3 ) fully exposed dorsally and laterally, juxtaposed, flattened dorsoventrally, subtriangular, tapering to rounded apex; cornea darkly pigmented, subterminal and lateral in position.

Antennular peduncle ( Fig. 3A, B View FIGURE 3 ) elongate, attaining approximately 0.6 times of carapace length, somewhat flattened dorsoventrally. Article 1 with mesial margin armed with 1 spiniform seta at proximal angle; ventromesial carina unarmed; stylocerite terminating in small spine, not reaching distal margin of article 1. Article 2 slightly longer than visible portion of article 1, slightly tapering distally, 3.5 times as long as basal width. Article 3 subquadrate, short, about 0.2 length of article 3. Lateral flagellum not subdivided, slightly longer than peduncle, aesthetasc-bearing portion restricted to distal 0.7 length; mesial flagellum distinctly longer and more slender than lateral flagellum.

Antennal peduncle ( Fig. 3A, B, G View FIGURE 3 ) with basicerite bearing small acute tooth on ventrolateral distal margin. Carpocerite slender, subcylindrical, reaching far beyond scaphocerite and exceeding distal margin of antennular peduncle. Scaphocerite suboval, reaching mid-length of article 2 of antennular peduncle; lateral margin slightly convex with curvature distal to mid-length (not sinuous), distolateral spine small, reaching convex distal margin of blade.

Mouthparts not dissected, appearing quite typical for Alpheidae . Maxilliped 2 with podobranch.

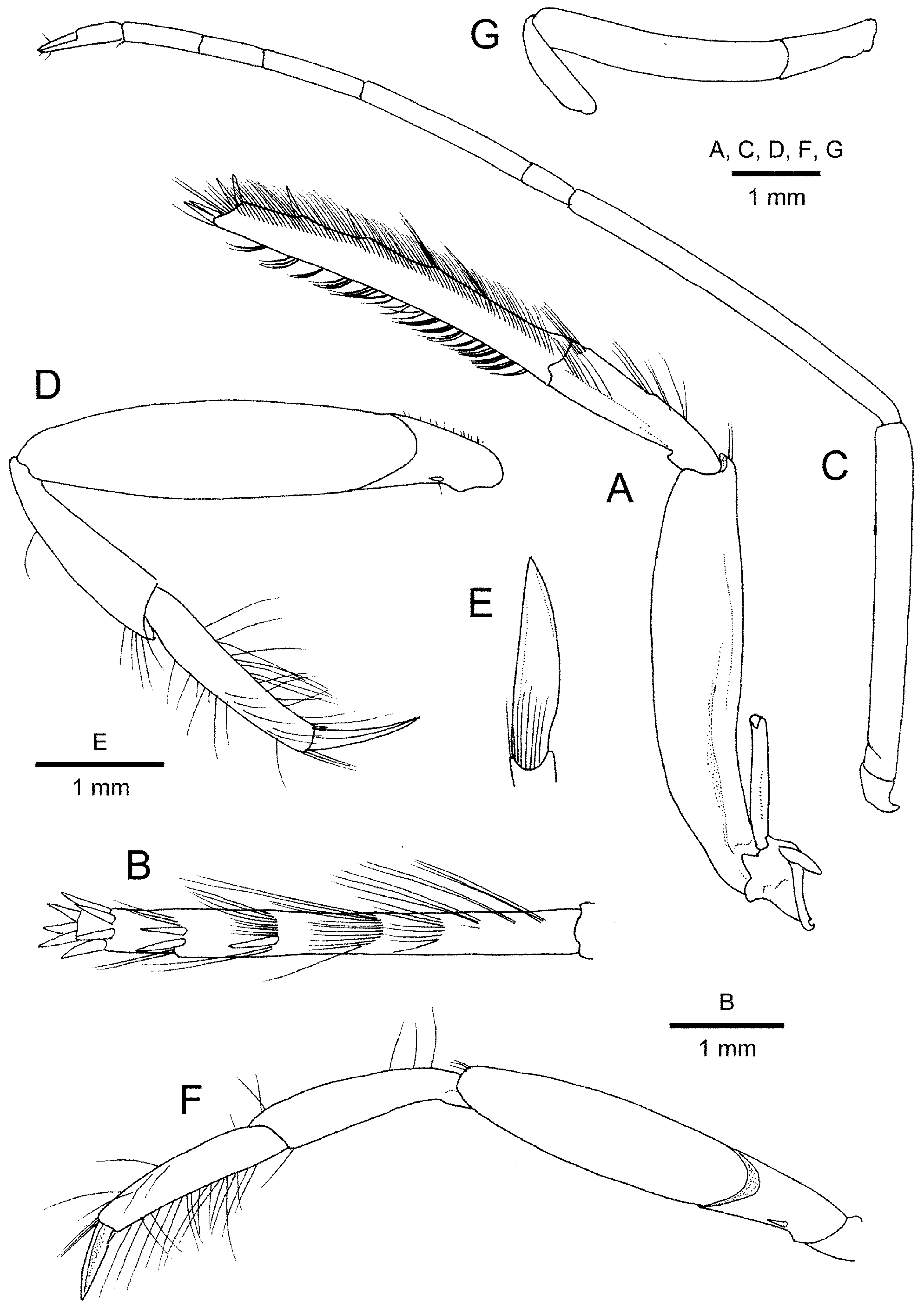

Maxilliped 3 ( Fig. 4A, B View FIGURE 4 ) elongate, total length of endopod approximately 1.5 times of carapace length, overreaching distal end of antennal carpocerite by 0.8 length of ultimate article. Coxal lateral plate conspicuous, bearing strap-like epipod. Antepenultimate article strongly compressed laterally; dorsal margin slightly uneven, forming distinct keel delimited laterally for proximal 0.8 length of article, distodorsal margin produced; ventral margin broadly convex in lateral view, forming narrow, flat face flanked by sharply delimited margins. Penultimate article about half-length of ultimate article; lateral surface with short longitudinal row of setae on distal half, aligned with setal rows on ultimate article; mesial surface almost glabrous. Ultimate article slightly tapering distally to obliquely truncate apex bearing cluster of 3 spiniform setae; dorsal surface with 5 evenly spaced, transverse rows of long spiniform setae and/or short to long setae, number of spiniform setae decreasing from most-distal to most-proximal, as following: 4 in distal-most row, 2 in second, 1 in third, none in fourth and fifth; lateral surface with row of numerous, moderately long setae adjacent to dorsal margin; mesial surface with numerous stiff setae composing grooming apparatus.

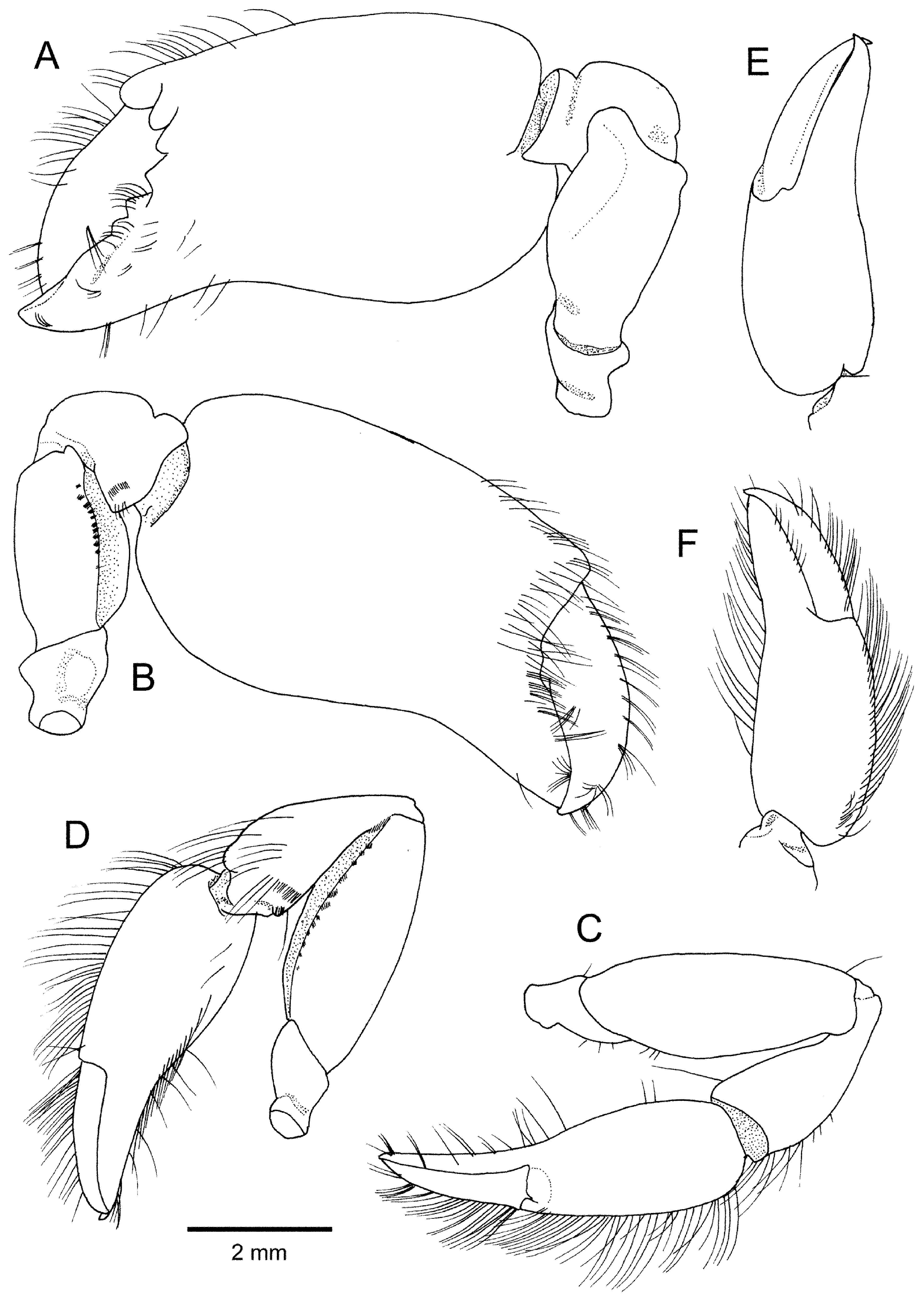

Pereopods 1 (chelipeds) strongly asymmetrical, left larger (in holotype). Left major cheliped of type I ( Figs. 1A View FIGURE 1 , 5A, B View FIGURE 5 ), very stout. Ischium unarmed, medially constricted. Merus stout, somewhat thickened in central portion, margins generally smooth, not rugose; dorsal margin rounded, with slight concavity proximally; lateral surface gently convex, distoventral angle produced into prominent rounded process; mesial surface nearly flat, with short row of minute setae adjacent to slightly sinuous ventromesial margin; ventrolateral margin sinuous; space between ventrolateral and ventromesial margin forming concave facet. Carpus short, robust, cup-shaped, subdistally with deep transverse groove on extensor surface. Chela subequal in length to carapace, somewhat compressed laterally; palm subrectangular in lateral view, 1.4 times as long as wide; dorsal surface rounded, slightly convex in lateral view, bearing row of moderately short setae on distal half; lateral surface gently convex, almost glabrous, distolateral margin articulating with dactylus divided into 3 lobes by deep notches; mesial surface gently convex, almost glabrous, except for submarginal row of setae extending along distomesial margin to occlusal margin of fixed finger; lower surface rounded, noticeably sinuous in lateral view. Fingers not gaping when closed. Fixed finger (pollex) short, robust, slightly deflexed, terminating in subacute tip; occlusal margin bearing 3 blunt triangular teeth in proximal half and slightly sinuous in distal half. Dactylus robust, about 0.6 times as long as palm; dorsal margin rounded, with row of moderately short setae; lateral surface almost glabrous; mesial surface with row of tufts of moderately short setae adjacent to dorsal margin; occlusal margin generally slightly sinuous, proximally with small shallow concavity; tips of fingers crossing.

Minor cheliped ( Fig. 5 View FIGURE 5 C–F) moderately stout, laterally compressed, chela much more slender compared to major cheliped. Ischium short, stout, distinctly constricted proximally, without conspicuous spiniform setae. Merus about twice as long as wide; dorsal margin rounded, slightly convex in lateral view; lateral and mesial surfaces almost glabrous, except for short, obliquely transverse rows of minute setae on mesial surface adjacent to ventromesial margin; ventrolateral and ventromesial margins clearly delimited, gently convex in lateral view, former with rounded distolateral lobe; ventral surface forming narrow facet. Carpus widened distally, cup-shaped, about twice as long as wide; extensor margin slightly depressed subdistally, with scattered setae extending onto mesial face; mesial face with grooming apparatus composed of shallow concavity and 2 short transverse rows of short stiff setae on distal flexor part. Chela 0.6 times as long as carapace, somewhat compressed dorsoventrally; palm subrectangular in lateral view, 1.6 times as long as wide; dorsal margin rounded, non-carinate, gently convex in outline, with row of moderately long setae over entire length; outer and inner surfaces gently convex, almost glabrous; lower margin also non-carinate, slightly convex in outline, with row of long setae extending onto pollex; pollex slightly deflexed, terminating in curved, acute tip, occlusal margin without conspicuous teeth. Dactylus moderately slender, subequal in length to palm, slightly arcuate, terminating in curved, acute tip; dorsal margin rounded, with row of moderately short setae aligned with setal row on palm; occlusal margin without conspicuous tooth; fingers not gaping; finger tips crossing.

Pereopod 2 ( Fig. 4C View FIGURE 4 ) slender, elongated, reaching beyond tip of maxilliped 3 when fully extended. Merus 1.1 times as long as ischium. Carpus 1.2 times as long as merus, subdivided into 5 sub-articles, their ratio from proximal to distal approximately equal to 1: 5.5: 3.1: 1.9: 2.4; chela subequal in length to distalmost carpal sub-article.

Pereopod 3 ( Fig. 4D, E View FIGURE 4 ) robust, laterally compressed; coxa with gonopore mesially, circumscribed by sparse setae; ischium armed with 1 ventral spiniform seta; merus unarmed, both dorsal and ventral margins gently convex; carpus without flexor distal spiniform seta; propodus slightly longer than carpus, with row of long setae, without spiniform setae; dactylus robust, flattened, subspatulate, slightly curved, approximately half-length of propodus, with acute tip. Pereopod 4 ( Fig. 4F View FIGURE 4 ) generally similar to pereopod 3, shorter; propodus subequal in length to carpus; dactylus less than half-length of propodus. Pereopod 5 ( Fig. 4G View FIGURE 4 ) damaged, right one missing, ischium and merus preserved in left one; ischium-merus distinctly shorter than those of pereopods 3 and 4, slightly curved upwards; ischium unarmed.

Pleopod 1 ( Fig. 3H View FIGURE 3 ) with small, lance-shaped endopod (about 0.2 length of exopod), with sparse marginal setae; exopod shorter than protopod; protopod with tuft of ovigerous setae at distomesial angle. Other pleopods missing.

Uropod distinctly exceeding telson ( Fig. 3C View FIGURE 3 ); endopod falling slightly short of exopod; exopod with 2 obtuse convexities on diaeresis, posterolateral corner weakly produced, blunt, with short spiniform seta adjacent and mesial to it.

Gill formula typical for Alpheidae : pleurobranchs on thoracic somites 4–8 (above bases of pereopods 1–5); 1 arthrobranch above base of maxilliped 3; strap-like epipods on maxilliped 3 and pereopods 1–4, corresponding setobranchs on pereopods 1–5.

Note on paratypes. Paratypes generally similar to holotype. Number of transverse rows of setae + spiniform setae on ultimate article of maxilliped 3 varying from 4 to 5. One of three paratypes with both chelipeds intact, major cheliped corresponding to type II ( Fig. 6 View FIGURE 6 A–D). Ischium unarmed, medially constricted. Merus moderately stout, slightly thickened in central portion, margins generally smooth; dorsal margin almost straight; lateral surface gently convex, distoventral angle produced into rounded process; mesial surface nearly flat, with short rows of minute setae adjacent to gently convex ventromesial margin; ventrolateral margin sinuous; space between ventrolateral and ventromesial margin forming concave facet. Carpus short, robust, cup-shaped, subdistally with deep transverse groove on extensor surface; ventrolateral distal angle somewhat produced into triangular lobe. Chela shorter than carapace, somewhat compressed laterally, rotated about 30° counterclockwise from perpendicular at articulation to carpus; palm subrectangular in lateral view, 1.6 times as long as wide; upper surface rounded, slightly convex in lateral view, bearing row of moderately long setae over entire length; outer surface gently convex, almost glabrous, distolateral margin articulating to dactylus divided into 3 unequal lobes; inner surface also gently convex, almost glabrous; lower surface rounded, gently sinuous in lateral view; pollex moderately long and slender, slightly deflexed, terminating in acute tip, occlusal margin only faintly dentate, without conspicuous tooth. Dactylus moderately slender, about 0.7 times as long as palm, gently curved; upper margin rounded, with row of moderately long setae; lateral surface almost glabrous; mesial surface with row of tufts of moderately short setae adjacent to upper margin; occlusal margin without conspicuous teeth or concavity; tips of fingers crossing. No hiatus between fingers when fully closed.

Pereopod 5 ( Fig. 6 View FIGURE 6 E–G) shorter than pereopods 3 and 4. Ischium unarmed. Merus slightly upcurved. Propodus 1.3 times as long as carpus, with grooming apparatus consisting of closely spaced transverse rows of stiff setae, increasing in length distally, in distal half of flexor margin; flexor distal margin without spiniform seta. Dactylus flattened, sickle-shaped, terminating in basally demarcated unguis, about 0.4 times as long as propodus; extensor margin bearing row of short setae in distal half.

Coloration in life. Holotype ( Fig. 1A, B View FIGURE 1 ): Body generally semitransparent, yellowish; carapace with small red dots in pairs on anterolateral angles, anterior part of gastric region, at about mid-length of flanks and cardiac region; major cheliped fingers and merus ivory-white, occlusal margins of fingers brownish; other appendages semitransparent; cornea dark gray with scattered white dots; ovary and hepatopancreas visible as yellow masses inside of cephalothorax; eggs yellow.

Paratype ( Fig. 2 View FIGURE 2 ): Body and appendages generally whitish transparent; stomach light brown; hepatopancreas visible as white mass; otherwise similar to holotype.

Distribution. Presently known only from Awaji Island, eastern part of the Seto Inland Sea, Japan.

Biological note. The specimens of the new species were collected at depth of 4–8 m on a muddy sand flat, with sparse clusters of sea grass, Zostera marina and Halophila ovalis , and scattered burrow openings, indicating the presence of a rich infauna. Noteworthy, an undescribed species of the laomediid mud shrimp genus Axianassa Schmitt, 1924 (Komai et al., in preparation) was collected at the same locality as A. awaji n. sp. Most members of Axianassa are known to burrow deep in soft sediments (e.g. Kensley & Heard 1990; Dworschak & Coelho 1999). It has been suggested that species of the Automate evermanni group probably live “commensally” in burrows of other animals, including callianassids and laomediids, although it remains to be confirmed (e.g. Dworschak & Coelho 1999; Anker et al. 2015; De Grave & Anker 2017).

Remarks. Of the four specimens examined, only the holotype and one of the paratypes possess both of their chelipeds. The holotype, which carries a very stout major cheliped of type I ( Fig. 5A, B View FIGURE 5 ), is an ovigerous female and the largest specimen of the type series. One of the three paratypes has both chelipeds, of which the major one could be attributed to type II ( Fig. 6 View FIGURE 6 A–D). In the three paratypes, gonopores are absent on the coxae of pereopods 3 and 5; therefore, the sex of these specimens could not be determined. The polymorphism of the major cheliped is clearly not related to the sex of the individuals, but more likely to the growth change, as shown for A. cf. evermanni by Dworschak & Coelho (1999). Wang & Sha (2017) also identified the sex of their specimens of A. anacanthopusoides with the type I major cheliped as females (illustrated specimens include the holotype and one of the paratypes), although they did not specifically comment on the major cheliped polymorphism in their species.

Automate awaji n. sp. is referred to the A. evermanni species group on account of the following features ( Anker & Komai 2004): (1) rostrum not concealing most part of eye-stalks, very short, triangular, not reaching to level of lateral margins of frontal concavity; (2) eyestalks parallel and mesially juxtaposed; (3) ventromesial carina on article 1 of antennular peduncle unarmed; (4) stylocerite not reaching distal margin of article 1 of antennular peduncle; (5) scaphocerite somewhat reduced, not reaching distal margin of article 2 of antennular peduncle; (6) maxilliped 2 with podobranch; (7) major chela more or less rounded in general outline, with ventral margin more or less constricted; (8) propodus of third pereopod without spiniform setae, however, with long stiff setae; (9) dactyli of pereopods 3 and 4 subspatulate; (10) uropodal endopod only slightly exceeding exopod; (11) diaeresis of uropodal exopod devoid of acute teeth laterally.

Anker & Komai (2004) referred five species to this group, viz., A. anacanthopus , A. branchialis , A. evermanni , A. rectifrons and A. rugosa . Wang & Sha (2017) referred their new species A. anacanthopusoides and A. spinosa Wang & Sha, 2017 to the A. evermanni group. Automate isabelae was compared with A. rugosa in the original description, although Ramos-Tafur (2018) claimed the distinctiveness of A. isabelae and A. rugosa . In spite of the original assignment, A. spinosa clearly belongs to the A. dolichognatha species group, because the propodi of the pereopods 3 and 4 bear stout spiniform setae on the flexor margins ( Wang & Sha 2017: fig. 4I–K). Indeed, A. rugosa and A. isabelae are quite distinctive in the dorsally and ventrally tuberculate major cheliped palm ( Wicksten 1981; Ramos-Tafur 2018), and thus it is not necessary to make detailed comparison with the new species. Potential diagnostic features differentiating the new species and the other five species in the A. evermanni group are discussed below (also summarised in Table 1).

(1) Automate anacanthopus was originally described on the basis of two specimens from Indonesia. None of them was intact and both were missing their major chelipeds (de Man 1910, 1911). Since de Man (1911), the species has been recorded from several Indo-West Pacific localities, including Madagascar, Réunion, Hong Kong, Vietnam, Indonesia, Papua New Guinea and Singapore ( Ledoyer 1970; Banner & Banner 1983; Bruce 1990; Anker 2001; Anker et al. 2015; Anker & De Grave 2016). Ledoyer (1970) and Bruce (1990) published figures of specimens from Madagascar and Hong Kong, respectively, whereas Anker et al. (2015) and Anker & De Grave (2016) published colour photographs of living specimens. Anker (2001: fig. 46) provided illustrations of chelipeds of three different specimens identified as A. anacanthopus ( Madagascar) and A. cf. anacanthopus ( Vietnam and Papua New Guinea). The author also noted that the identity of the specimens reported by Bruce (1990) was questionable because of substantial differences in the cheliped morphology between them and Ledoyer’s (1970) specimens. Wang & Sha (2017) believed that the specimens reported by Ledoyer (1970) might represent A. anacanthopusoides . However, a more thorough comparison showed that Ledoyer’s (1970) material differs from that of A. anacanthopusoides in some features, as discussed below. For all the reasons, the comparison between A. awaji n. sp. and A. anacanthopus must be based solely on de Man’s (1911) description of the type material.

The new species can be readily distinguished from A. anacanthopus by the shape of the antennal scaphocerite: in A. awaji n. sp., the distolateral spine of the scaphocerite is very small, only reaching as far as the rounded distal margin of the blade ( Fig. 3G View FIGURE 3 ); in contrast, in A. anacanthopus , the distolateral spine is very slender and elongate, extending far beyond the obliquely truncate distal blade (de Man 1911: pl. 1, fig. 3). The cornea is comparatively small and located in the distolateral position of the eyestalk in the new species ( Fig. 3B View FIGURE 3 ), whereas it is comparatively larger and located in the more subterminal and median position of the eyestalk in A. anacanthopus (cf. de Man 1911: pl. 1, fig. 3). The ischium of the minor cheliped is unarmed in A. awaji n. sp. ( Fig. 5C, D View FIGURE 5 ), whereas armed with a long spiniform seta on the dorsal margin in A. anacanthopus (cf. de Man 1911: pl. 1, fig. 3b).

(2) Automate anacanthopusoides was originally described on the basis of 22 specimens, including the ovigerous female holotype, from Beibu Gulf in the South China Sea. Comparison with the original description by Wang & Sha (2017) reveals a series of differences between the two species. The lateral margin of the antennal scaphocerite is slightly convex in distal to the mid-length in A. awaji n. sp. ( Fig. 3G View FIGURE 3 ), rather than slightly concave in A. anacanthopusoides ( Wang & Sha 2017: fig. 1B); its distolateral tooth is very short and reaches as far as the rounded distal blade in the new species ( Fig. 3G View FIGURE 3 ), whereas it is long and distinctly overreaches the blade in A. anacanthopusoides ( Wang & Sha 2017: figs. 1B, 2K, O). The cornea is relatively smaller in A. awaji n. sp. than in A. anacanthopusoides ( Fig. 3B View FIGURE 3 versus Wang & Sha 2017: figs. 1B, 2K, O). The cheliped ischia are unarmed in A. awaji n. sp. ( Fig. 5 View FIGURE 5 A–D, 6A, B), in contrast, bearing a semicircular row of minute spiniform setae on the mesial face and one strong spiniform seta on the dorsal margin in A. anacanthopusoides , ( Wang & Sha 2017: fig. 1C, E). Within Automate , this characteristic armature of the cheliped ischia seems to be unique to A. anacanthopusoides . The major chela of type I is less stout in A. awaji n. sp. than in A. anacanthopusoides (cf. Fig. 5A, B View FIGURE 5 versus Wang & Sha 2017: figs. 1C, D, 2P); the ventral margin of the palm is evenly sinuous, entirely smooth in A. awaji n. sp. ( Fig. 5A, B View FIGURE 5 ), rather than rugose distal to a deep notch at the base of the fixed finger in A. anacanthopusoides (cf. Wang & Sha 2017: figs. 1C, D, 2P); the mesial surface of the palm is almost glabrous except for a submarginal row of setae adjacent to the dactylar articulation in A. awaji n. sp. ( Fig. 5B View FIGURE 5 ), whilst being covered with numerous long setae in A. anacanthopusoides ( Wang & Sha 2017: figs. 1C, 2P); the chela fingers do not gape, when closed, in A. awaji n. sp. ( Fig. 5A, B View FIGURE 5 ) versus leaving a wide gape in A. anacanthopusoides ( Wang & Sha 2017: figs. 1C, D, 2P).

Wang & Sha (2017) suggested that the specimens reported by Ledoyer (1970) as A. anacanthopus from Madagascar could represent A. anacanthopusoides . Anker (2001: fig. 46e, f) also illustrated a major cheliped of one of the specimens reported by Ledoyer (1970). Some differences can be observed between the Madagascar and the South China Sea specimens, at least based on the illustrations provided by Ledoyer (1970), Anker (2001) and Wang & Sha (2017). The distal blade of the specimen from Madagascar was illustrated as obliquely truncate by Ledoyer (1970: pl. 17, fig. a, b A2) and as rounded in A. anacanthopusoides by Wang & Sha (2017: fig. 1B); the mesial face of the ischium of at least the major cheliped is unarmed in the specimens from Madagascar ( Ledoyer 1970: pl. 17, fig. a P1G) versus bearing a subcircular row of minute spiniform setae on both cheliped ischia in A. anacanthopusoides (cf. Wang & Sha 2017: fig. 1C, E). It is likely that the specimens from Madagascar might represent a species other than A. anacanthopusoides , but careful reexamination of the voucher material would be necessary to fully assess the taxonomic identity of the Madagascar specimens.

(3) Automate branchialis was originally described on the basis of 19 specimens from the Mediterranean coast of Israel, with a female from Gaza designated as holotype ( Holthuis & Gottlieb 1958). Since the original description, A. branchialis has been reported from almost the entire Mediterranean Sea (e.g. Froglia 1975; Števčić 1979; Koukouras et al. 1993; Kocataş & Katagan 2003; Box et al. 2007; García Raso et al. 2010, 2018; Grimes et al. 2016; Ceseña et al. 2017). In spite of many published records, however, only the original description by Holthuis & Gottlieb (1958) provides a good basis for comparison with the new species. Automate awaji n. sp. can be distinguished from A. branchialis by a series of morphological features. The cornea of the eye is smaller in A. awaji n. sp. than in A. branchialis (the corneal width is much less than half of the eyestalk width in A. awaji , rather than about half of it in A. branchialis ) (cf. Fig. 3 B View FIGURE 3 and Holthuis & Gottlieb 1958: fig. 5q). The antennal peduncle carpocerite distinctly overreaches the distal end of the antennular peduncle in A. awaji n. sp. ( Fig. 3A, B View FIGURE 3 ), rather than reaching or slightly overreaching it in A. branchialis (cf. Holthuis & Gottlieb 1958: fig. 5b). The maxilliped 3 ultimate article bears a fine row of short setae on the lateral surface adjacent to the dorsal margin in A. awaji n. sp. ( Fig. 4A View FIGURE 4 ), while such a setal row is absent in A. branchialis (cf. Holthuis & Gottlieb 1958: fig. 5h). The ischia of the chelipeds are unarmed in A. awaji n. sp. ( Figs. 5 View FIGURE 5 A–D, 6A, B), but they are armed with one spiniform seta on each dorsal and ventral margin in A. branchialis (cf. Holthuis & Gottlieb 1958: figs. 5i, j, 6a). The merus of the type II major cheliped and minor cheliped is unarmed in A. awaji n. sp. (Fig. Fig. 5 View FIGURE 5 A–D), while armed with two spiniform setae proximally on the ventral surface in A. branchialis (cf. Holthuis & Gottlieb 1958: figs. 5i, j). The fingers of the type I major cheliped are completely closed in A. awaji n. sp. ( Fig. 5A, B View FIGURE 5 ), while they leave a wide gape in A. branchialis ; the dactylus is distinctly shorter than the palm in A. awaji n. sp. ( Fig. 5A, B View FIGURE 5 ), rather than being subequal in the length to the palm in A. branchialis (cf. Holthuis & Gottlieb 1958: fig. 6a). The first carpal sub-article of the pereopod 2 is much less than half-length of the second sub-article in A. awaji n. sp. ( Fig. 4C View FIGURE 4 ), while about half-length in A. branchialis (cf. Holthuis & Gottlieb 1958: fig. 6b). The propodus of pereopod 5 bears only grooming setae on the flexor margin in A. awaji n. sp. ( Fig. 6E, F View FIGURE 6 ), but is armed with a row of about seven spiniform setae on the flexor margin, in addition to grooming setae, in A. branchialis (cf. Holthuis & Gottlieb 1958: fig. 6d).

(4) Automate evermanni was originally described on the basis of three specimens from Aguadilla, Puerto Rico, which were determined as two males and a female, and additional material (number of specimens not specified) from Mayaguez Harbor, also in Puerto Rico ( Rathbun 1901). Since the original description, the species has been reported from both western and eastern Atlantic ( Holthuis 1951; Crosnier & Forest 1966; Williams 1984; Abele & Kim 1986; Martinez-Iglesias 1986; Blanco Rambla & Linero Arana 1994; Martinez-Iglesias et al. 1996; Christoffersen 1998; Dworschak & Coelho 1999; Coelho et al. 2006; Souza et al. 2011; Almeida et al. 2012, 2018; Felder et al. 2019). However, Anker (2001) noted that the identity of the Brazilian and West African specimens was uncertain and that they might represent different species. De Grave & Anker (2017) also suggested that A. evermanni , as currently diagnosed, represents a species complex. Therefore, the present comparison relies only on the original description of Rathbun (1901), supplemented by Chace (1972, 1988). In his key to the species of Automate, Chace (1988: 64) used the armature of the antennal basicerite in discriminating A. branchialis (basicerite armed with a minute distal tooth near the base of the scaphocerite) from A. evermanni and A. rugosa (basicerite unarmed distally). In A. awaji n. sp., the basicerite is armed with a ventrolateral distal spine ( Fig. 3F View FIGURE 3 ), differing from A. evermanni in this regard. The distolateral tooth of the antennal scaphocerite is short and does not overreach the distal margin of the blade in A. awaji n. sp. ( Fig. 3G View FIGURE 3 ), whereas it distinctly overreaches the distal blade in A. evermanni (cf. Rathbun 1901: fig. 22a). Rathbun (1901) mentioned the two forms of the major cheliped in the type material. With regard to the type I, A. awaji n. sp. differs from A. evermanni in the more stout chela with a strongly produced dorsodistal margin at the base of the dactylus and the more strongly sinuous, unarmed ventral margin (cf. Fig. 5A, B View FIGURE 5 and Rathbun 1901: fig. 22b; Rathbun specifically noted that the ventral margin of the chela is granulated at about the mid-length in A. evermanni ); the fingers are completely closed in A. awaji n. sp. ( Fig. 5A, B View FIGURE 5 ), rather than gaping in A. evermanni ( Rathbun 1901: 112, fig. 22b); the carpus has a deep subdistal transverse groove on the dorsal surface in A. awaji n. sp. ( Fig. 5A, B View FIGURE 5 ), whereas such a groove is absent in A. evermanni (cf. Rathbun 1901: fig. 22b); the merus has a prominent, rounded ventrodistal lateral projection and a strongly sinuous ventral margin in A. awaji n. sp. ( Fig. 5A View FIGURE 5 ), but in contrast, in A. evermanni , it does not have a prominent projection at the ventrolateral distal angle and with a gently convex ventral margin ( Rathbun 1901: fig. 22b).

(5) Automate rectifrons was originally described on the basis of female holotype from Bahía de la Ascensión, Quintana Roo, Mexico, and one fragmented juvenile from Antigua, Lesser Antilles ( Chace 1972). Subsequently, the species has been scarcely recorded from Florida to Brazil ( Abele & Kim 1986; Soledade et al. 2015; De Grave & Anker 2017; Felder et al. 2019). Soledade et al. (2015) provided a brief account accompanied with figures of selected parts on the basis of a single specimen from Abrolhos, Brazil. When the figure of Soledade et al. (2015) and that of the holotype are compared, the following discrepancies are found: the posterior margin of the telson is armed with two pairs of greatly unequal spiniform setae in the specimen from Brazil, rather than only one pair of moderately long spiniform setae in the holotype; the antennal peduncle distinctly overreaches the end of the antennular peduncle in the specimen from Brazil, whereas it just reaches the latter in the holotype; the eyestalk tapers more strongly in the specimen from Brazil than in the holotype; the lateral margin of the antennal scaphocerite is gently convex in the specimen from Brazil, rather than faintly sinuous in the holotype; the uropod is relatively shorter in the specimen from Brazil than in the holotype. Soledade et al. (2015) pointed also the differences in the major cheliped shape between their specimen and the holotype, but those differences seem to be attributable to polymorphism generally seen in species of Automate . It is likely that the specimen from Brazil represent a species distinct from A. rectifrons . Consequently, the following comparison is restricted to the original description by Chace (1972).

Automate awaji n. sp. is rather easily distinguished from A. rectifrons by the presence of a tiny rostrum ( Fig. 3B View FIGURE 3 ) (versus rostrum absent in A. rectifrons ; Chace 1972: fig. 24b), the much smaller cornea located at the distolateral position of the eyestalk ( Fig. 3A View FIGURE 3 ) (versus cornea distinctly larger, occupying the distal portion of the eyestalk; Chace 1972: 24 a, b), the comparatively long antennal carpocerite (distinctly overreaching the distal end of the antennular peduncle versus only reaching it), the proportionally shorter article 1 of the pereopod 2 carpus (much less than half length of the article 2 in A. awaji n. sp. versus about half length of the latter in A. rectifrons ) ( Fig. 4C View FIGURE 4 versus Chace 1972: fig. 24n), and the grooming apparatus on the pereopod 5 propodus consisting of closely spaced transverse rows of stiff setae in the distal half ( Fig. 6F View FIGURE 6 ) (versus consisting of seven clearly separated, transverse rows of short stiff setae in the distal half and two widely separated spiniform setae on the mesial surface in A. rectifrons ; Chace 1972: fig; 24q). The major cheliped of the holotype of A. rectifrons seems to represent the type I: the ischium has a spiniform seta on the dorsal margin (cf. Chace 1972: fig. 24m), but such a seta is absent in A. awaji n. sp. ( Fig. 5A, B View FIGURE 5 ); there is no transverse groove on the dorsal surface of the carpus (cf. Chace 1972: fig. 24m), whereas the carpus has a deep transverse groove on the dorsal surface in A. awaji n. sp. ( Fig. 5A, B View FIGURE 5 ). The telson posterior margin of the holotype of A. rectifrons is armed only with one pair of spiniform setae ( Chace 1972: fig. 24b), as noted above, but this condition is rather exceptional in the A. evermanni species group. In the present specimens of A. awaji n. sp., there are two pairs of greatly unequal setae there ( Fig. 3D, E View FIGURE 3 ), as in other species in the species group. If the condition in the holotype of A. rectifrons is normal, this character could be diagnostic for A. rectifrons .

Etymology. The specific epithet “awaji” refers to the island, which harbors the type locality of the new species. Used as a noun in apposition.

| T |

Tavera, Department of Geology and Geophysics |

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.

|

Kingdom |

|

|

Phylum |

|

|

Class |

|

|

Order |

|

|

Family |

|

|

Genus |