Donacospiza albifrons, (Vieillot, 1817) (Vieillot, 1817)

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/ 10.11646/zootaxa.4329.3.1 |

|

publication LSID |

lsid:zoobank.org:pub:A1Fa25B9-E28F-407A-B1Ec-4E78A952E472 |

|

DOI |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.5671871 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/386687B4-0F67-336E-4983-957EFC637BAD |

|

treatment provided by |

Plazi |

|

scientific name |

Donacospiza albifrons |

| status |

|

The Long-tailed Reed Finch Donacospiza albifrons ( Vieillot, 1817) is a patchily distributed species found in reed beds, damp grasslands, and scrubs, usually near water, ranging from southeastern Brazil to Uruguay, northeastern Argentina and Paraguay ( Parker et al. 1996; Ridgely & Tudor 2009; Jaramillo 2011). An allopatric population is found in the seasonally wet grasslands of Bolivia ( Schimitt & Schimitt 1987; Brace & Hornbuckle 1998; Maillard et al. 2008; Lane 2014), isolated by almost 1,000 km of intervening dry habitats.

The species is rare in collections and few institutions harbor series larger than 10 specimens, always with limited geographical coverage. Consequently, the large morphological variation observed in the species has been attributed, to a variable extent, to age and/or sex by previous authors, with considerable disagreement. Some authors describe females as slightly paler below and more striated above ( Sharpe 1888; Hellmayr 1938; Meyer de Schauensee 1970; Armani 1985; Dunning 1987; Ridgely & Tudor 1989; Perlo 2009). Jaramillo (2011) states that the “female is very like male, perhaps slightly less colourful, but much overlap in appearance.” Some other authors consider that sexual dichromatism does not exist and attribute morphological variation exclusively to age ( Narosky & Yzurieta 2003; Willis & Oniki 2003; Grantsau 2010; Azpiroz 2012) and feather wear, with the cinnamon-buff underparts becoming whitish in specimens with very abraded plumage ( Azpiroz 2012). No author has ever reported geographic variation in the species, although Lane (2014), after comparing specimens from Bolivia and southeastern Brazil, suggested that the taxonomy of the species should be investigated.

While collecting birds in the Espinhaço Range, southeastern Brazil, I obtained Long-tailed Reed Finch specimens that were much paler and less streaked on the upperparts than depicted in popular field guides (e.g. Ridgely & Tudor 2009). These birds were collected in dry grasslands at high elevations (ca. 1500 m asl), a habitat quite distinct from that previously reported for the species, which is usually found near water and at lower elevations. Initially, I suspected I had collected an undescribed species, especially because the Espinhaço Range is a well-known center of bird endemism ( Stattersfield et al. 1998; Vasconcelos et al. 2008) from where new species have recently been described ( Vielliard 1990; Gonzaga et al. 2007; Whitney et al. 2010; Freitas et al. 2012).

Nevertheless, after collecting additional specimens and analyzing the largest series of Long-tailed Reed Finches in any study, I found that my initial hypothesis was incorrect. Here I present a detailed study of the morphological variation in the species, including its plumage sequence and a revision of its taxonomy. Before proceeding, a brief review of the taxonomic history of the species is presented.

Taxonomic and nomenclatural history. Sylvia albifrons Vieillot, 1817 , is based on “Cola Aguda del Vientre de Canela”, bird number CXXXIV of Azara (1805), who observed the species in Paraguay. Vieillot (1817) did not clearly state whether he had examined any specimens, but he probably based the description exclusively on the writings of Azara (1805).

Systematic relationships of the species have long been disputed. The monospecific genus Donacospiza Cabanis was erected for the bird described by Vieillot ( Cabanis & Heine 1850 –1851), but the species has also been placed in the genus Poospiza Cabanis by Sclater (1864), Emberizoides Temminck by Gray (1870), and Coryphaspiza G. R. Gray by Sharpe (1888).

The species has been traditionally placed among the emberizid passerines (e.g. Sharpe 1888; Hellmayr 1938; Paynter & Mayr 1970), but recent molecular studies showed that Donacospiza is best placed among the Thraupidae , embedded within the subfamily Poospizinae, in a clade containing Cypsnagra Lesson and Poospizopsis von Berlepsch ( Lougheed et al. 2000; Shultz & Burns 2012; Barker et al. 2013a; Burns et al. 2014, 2016). Strong reciprocal response to cross playback of D. albifrons has been observed for the Cinereous Warbling Finch Microspingus cinereus (Bonaparte) ( Ribon 2002) and the Black-and-rufous Warbling Finch Poospiza nigrorufa (d’Orbigny & Lafresnaye) ( Rising 2011) , providing additional evidence of the close relationship between these genera.

The Long-tailed Reed Finch includes as junior synonyms two other names, which are discussed below.

Ammodramus longicaudatus Gould, 1839 , was described from birds collected by Charles Darwin during his voyage aboard the H.M.S. Beagle (Darwin 1838–1841; Steinheimer 2004; Steinheimer et al. 2006). This name was based on an unspecified number of syntypes collected in Montevideo and Maldonado, Uruguay (Darwin 1838– 1841). Sharpe (1888) cited two “adult” birds collected by Darwin and deposited in the Natural History Museum, specimen “h” from Maldonado and specimen “i” from Montevideo, referring this last specimen as the type of this name. Warren (1971) and Steinheimer (2004) considered both specimens as syntypes.

Poospiza oxyrhyncha Sclater, 1864 , was described from a female obtained in exchange with the “ Vienna Museum”. The type locality is Curitiba, state of Paraná, southern Brazil ( Sclater 1864) and the holotype is housed in the Natural History Museum ( Warren & Harrison 1971). Sclater (1869) soon recognized that the name proposed by him was a junior subjective synonym of that proposed by Vieillot (1817).

Material and methods

During the last ten years, I conducted limited fieldwork in the state of Minas Gerais, southeastern Brazil, searching for the Long-tailed Reed Finch. I collected specimens with mist-nets and air rifles and took notes on habitat.

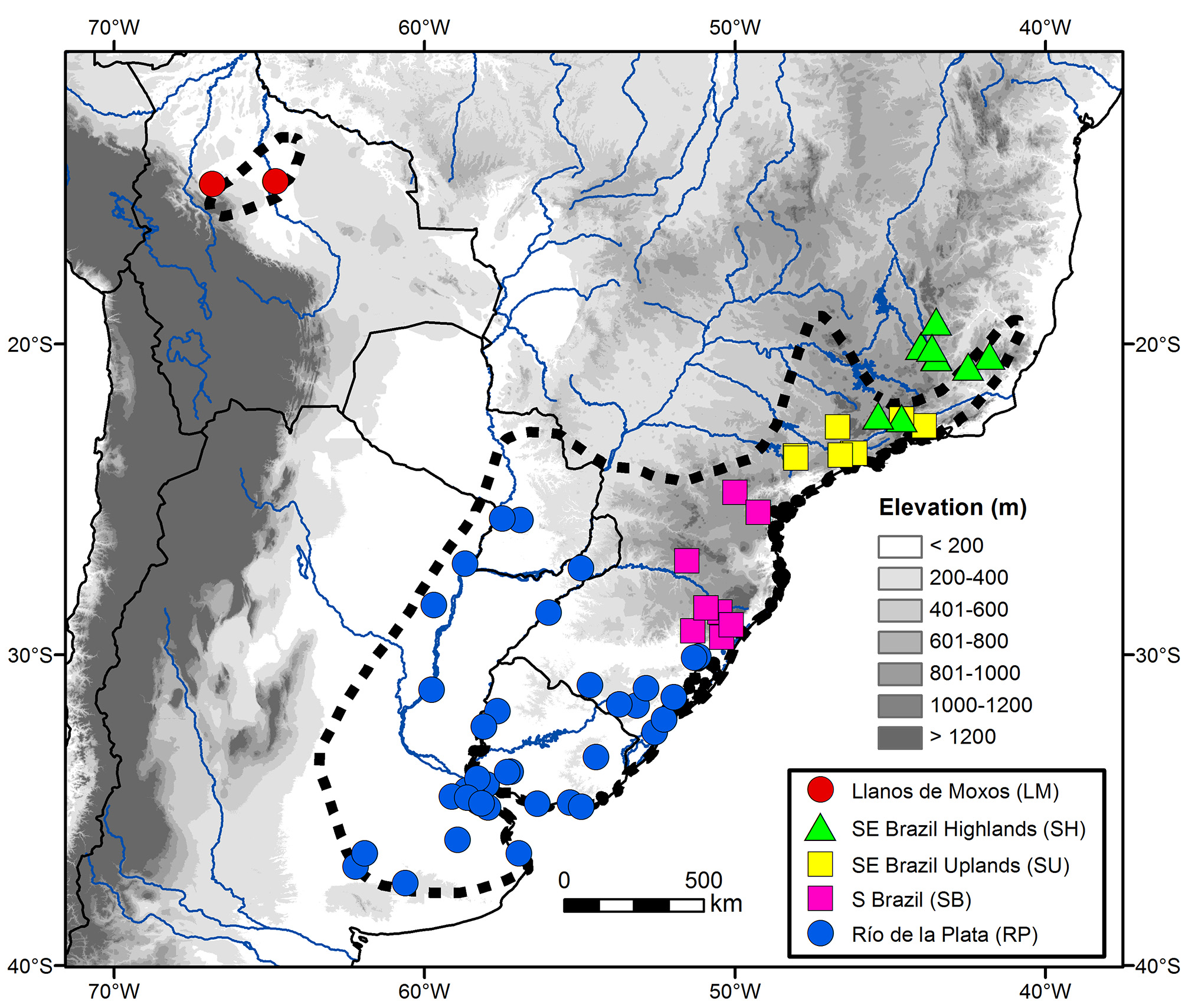

The taxonomic and morphological analyses conducted here were based on plumage coloration and morphometric characters of 141 specimens (Appendix 1, Figure 1 View FIGURE 1 ) housed in 18 ornithological collections: Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia, Philadelphia, USA ( ANSP); American Museum of Natural History, New York, USA ( AMNH); Carnegie Museum of Natural History, Pittsburgh, USA (CM); Centro de Coleções Taxonômicas da Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais, Belo Horizonte, Brazil (DZUFMG); Field Museum, Chicago, USA ( FMNH); Louisiana State University Museum of Natural Science, Baton Rouge, USA ( LSUMZ); Museu de Ciências Naturais da Pontifícia Universidade Católica de Minas Gerais, Belo Horizonte, Brazil ( MCNA); Muséum National D’Histoire Naturelle, Paris, France ( MNHN); Museu Nacional, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil ( MNRJ); Museu Paraense Emílio Goeldi, Belém, Brazil ( MPEG); Museu de Zoologia João Moojen da Universidade Federal de Viçosa, Viçosa, Brazil ( MZJMO); Museu de Zoologia da Universidade de São Paulo, São Paulo, Brazil ( MZUSP); Natural History Museum, Tring, UK ( NHMUK; formerly BMNH); Naturhistorisches Museum, Vienna, Austria ( NMW); Naturhistoriska Riksmuseet, Stockholm, Sweden ( NRM); Senckenberg Naturmuseum, Frankfurt, Germany ( SMF); National Museum of Natural History, Washington, DC, USA ( USNM); and Museum für Naturkunde, Berlin, Germany ( ZMB).

I examined the holotype of Poospiza oxyrhyncha Sclater, 1864 ( NHMUK 1885.2.10.314), and one syntype of Ammodramus longicaudatus Gould, 1839 ( NHMUK 1856.3.15.9). The other syntype of A. longicaudatus ( NHMUK 1856.3.15.13) was not found. The type of Sylvia albifrons Vieillot, 1817 , was not found in any of the collections visited and I failed to trace its location. I believe that this type, if once preserved, is lost, as is the rule for birds described by Vieillot from the works of Azara ( Lopes & Gonzaga 2016a). Geographical coordinates were obtained directly from the original sources or from ornithological gazetteers ( Paynter 1989, 1992, 1995; Paynter & Traylor 1991; Vanzolini 1992).

The first step in the interpretation of color variation in the Long-tailed Reed Finch was to identify its plumage sequence and molting patterns, for which I followed the Humphrey & Parkes (1959) system. To determine the approximate schedule of breeding and molting in the species, for which no previous study was available, I conducted a thorough literature review and checked for gonadal data on labels of museum specimens. Given that the species lives in an abrasive habitat and feather wear results in significant changes in plumage color ( Azpiroz 2012), I classified the plumage of each specimen accordingly to its stage of overall feather abrasion (Rogers 1 990): new, slightly abraded, abraded, and very abrade. This simple classification aided evaluation of the impact of feather abrasion upon plumage coloration. I used a color catalogue ( Munsell Color 2000) as an aid for plumage comparisons and a dial caliper for measuring to the nearest 0.1 mm the length (mm) of total culmen, closed wing (chord), tail, and tarsus ( Baldwin et al. 1931).

Delimitation of groups. Given the large color and morphometric variation observed in the Long-tailed Reed Finch, as well as the lack of previous taxonomic hypotheses regarding it, I tentatively used three approaches to delimit groups within the taxon. First, I attempted several clustering techniques (e.g. UPGMA with Euclidian Distances; Tabachnick & Fidell 2007) to identify naturally occurring groups based on body size alone, without delimiting them a priori. This technique was ineffective, because birds collected in the same or in very close localities appeared scattered throughout the dendrogram, with no consistent trend (data not shown). Second, I attempted to delimit groups based on plumage coloration alone, but as discussed below, I was unable to delimit clear-cut boundaries between populations. Third, I divided the examined specimens into five groups based on geographic and habitat features, roughly following the limits, but not the names, of those biogeographical provinces recognized by Morrone (2014): 1) RP—Río de la Plata (lowlands below 400 m in Paraguay, Argentina, Uruguay, and the Brazilian state of Rio Grande do Sul); 2) SB—Southern Brazil (uplands between 700–1200 m in the states of Rio Grande do Sul, Santa Catarina, and Paraná); 3) SU—Southeastern Brazil Uplands (areas between 400–800 m in the states of São Paulo and Rio de Janeiro); 4) SH—Southeastern Brazil Highlands (above 1200 m in the states of Minas Gerais, Rio de Janeiro, and Espírito Santo); and 5) LM—Llanos de Moxos (lowlands below 200 m in Bolivia). Groups delimited in this third approach were used in the following statistical analyses, which only considered specimens in definitive basic plumage (see below).

Statistical analyses. Differences between mean measurements of males and females were tested with the Student's t-test ( Zar 2010). Given that preliminary analyses revealed that the species shows geographic variation in body size (see below), this test was performed only with specimens from the Río de la Plata, the only region from where samples were large enough for testing. Given the small sample sizes and the large standard deviations of some groups, I did not conduct statistical comparisons between mean measurements of them, because investigating diagnosability is more important than simply pointing out mean differences between populations ( Patten & Unitt 2002). Therefore, I present box plot comparisons between body measurements of the five groups identified here and assessed their diagnosability using the method proposed by Patten & Unitt (2002). I also conducted a principal component analysis (PCA) with varimax rotation using the following variables: length of total culmen, closed wing, tail, and tarsus ( Tabachnick & Fidell 2007).

I investigated the hypothesis of clinal variation in body size with respect to Bergmann’s Rule ( Rensch 1938; James 1970), the tendency of organisms to be smaller in warmer areas and larger in colder areas ( Zink & Remsen 1986; Blackburn et al. 1999; Meiri 2011). I tested this hypothesis with the Spearman's correlation coefficient ( Zar 2010) comparing body size (measured as the first principal component scores, Zink & Remsen 1986) and average mean annual temperature at each collection site. For this analyses I conducted a second PCA with the same morphometric variables, but extracted only one component. Data from mean annual temperature (current conditions ~1960–1990) were obtained from WorldClim 1.4 with a spatial resolution of 30 seconds ( Hijmans et al. 2005). All analyses were performed using STATISTICA 8.0 software ( StatSoft 2007), with a significance level of 5%.

Results

The Long-tailed Reed Finch is locally distributed in Minas Gerais. I met with it in five localities in the Southeastern Brazil Highlands, all of them in the southern portion of the Espinhaço Range: Parque Nacional da Serra do Cipó, Morro do Pilar (19°16’S, 43°31’W, 1250–1350 m), Parque Estadual do Rola Mola, Brumadinho (20°03’S, 44°00’W, 1400–1500 m), Retiro das Pedras, Nova Lima (20°05’S, 44°00’W, 1300 m), Saramenha, Ouro Preto (20°24’S, 43°33’W, 1300–1400 m), and Parque Estadual do Itacolomi, Ouro Preto (20°25’S, 43°30’W, 1300–1550 m). In all these localities, the Long-tailed Reed Finch was found in mountainous areas with steep slopes covered by dry open grasslands with few shrubs and trees, usually with rock outcrops and always far from water ( Figure 2 View FIGURE 2 ). I collected eight specimens that were deposited in DZUFMG (see below), which represent the first specimens obtained in the central portion of Minas Gerais.

Breeding season. Males with enlarged testes were collected in Sep (SH—DZUFMG 7164, 7165; RP—USNM 630463), Oct (LM—LSUMZ 124921, 124922) and Jan (SH—DZUFMG 4895). A female collected on 8 Nov 1979 presented a well-developed egg in its oviduct (SU—MPEG 33275). Specimens collected in Jun–Aug presented small gonads. Therefore, breeding season of this species extends from at least Sep–Jan.

Plumage sequence, feather abrasion, and molts. I detected no sexual dichromatism in the Long-tailed Reed Finch, and the large variation in color can be attributed, to a variable extent, to age, plumage condition, and geography. I identified three distinct and well-marked plumages in the species: juvenal, first basic, and definitive basic ( Figure 3 View FIGURE 3 ). The Long-tailed Reed Finch does not exhibit an alternate plumage.

Juveniles were collected in Nov (RP—USNM 55789, with abraded plumage), Dec (SB—AMNH 315995, with abraded plumage; SU—AMNH 315990 and 315994, with severely abraded plumage; RP—AMNH 388282 and 388283, with severely abraded plumage), and Feb (SU—MZUSP 355, with slight abraded plumage). All but one specimen collected in Nov and another in Dec were molting to a variable extent into the first basic plumage. Therefore, Long-tailed Reed Finches seem to retain the juvenal plumage for about two months after fledging. An additional specimen in the juvenal plumage (RP—NHMUK 1897.11.14.35, slightly abraded) was collected on 29 Jun in Argentina.

Birds in first basic plumage, but showing a few remaining juvenal contour feathers scattered throughout the body (i.e. finishing the first prebasic molt), were collected in Oct (LM—LSUMZ 124924, 124926), Jan (SH— DZUFMG 4897), Feb (SU—LSUMZ 68294), and Mar (SH—MNRJ 27697). Birds in first basic plumage were collected in Feb (RP—AMNH 813075), Mar (SB—MZUSP 38907), Apr (SB—MNRJ 37640), Jun (RP— NHMUK 1856.3.15.9), Aug (RP—AMNH 519698 and ZMB 2000/27004), Oct (LM—LSUMZ 124920), and Nov (RP—AMNH 519693). Therefore, first basic plumage is retained for at least six months.

Body feathers of definitive plumaged birds are generally new from Mar onwards, with first signs of wear on Jul–Aug. Plumage becomes progressively worn until reaching a very abraded state in Feb and early Mar ( Figure 3 View FIGURE 3 ), when molt begins. Therefore, molt seems to occur just after the breeding season. A similar molting pattern seems to occur throughout the range of the species.

Plumage appearance. The three plumages of topotypical specimens (i.e., those from Paraguay, the type locality of the species, or nearby along the Río de la Plata) with new plumage are described below. I also present comments on variation in plumage coloration caused by feather abrasion ( Figure 3 View FIGURE 3 ) and geography ( Figures 4 View FIGURE 4 and 5 View FIGURE 5 ).

Juvenal plumage: Birds in this plumage are identifiable by their fluffy appearance, predominantly pale yellow throughout, and heavily streaked upperparts, breast, and sides. Crown, nape, interscapulars, and rump feathers very dark brown (10YR 2/2) edged (1–2mm) pale yellow (2.5Y 8/4), resulting in a heavily streaked appearance; underparts (chin, throat, breast and belly) pale yellow (2.5Y 8/3), with the feathers of the breast and sides presenting the central shafts very dark grayish brown (10YR 3/2); lores and indistinct supercilium pale yellow (2.5Y 8/4); auriculars grayish brown (2.5Y 5/2); primaries and secondaries very dark grayish brown (10YR 3/2) edged dark grayish brown (2.5Y 4/2) on the outer vanes; greater and marginal wing coverts, as well as tertials, very dark grayish brown (10YR 3/2) edged pale yellow (2.5Y 7/4); rectrices very dark grayish brown (10YR 3/2) edged dark grayish brown (2.5Y 6/4) on the outer vanes; under wing coverts pale yellow. Individual, wear, and geographic variation: difficult to appreciate, given that only a few specimens, several of them molting to the first basic, were available for examination. Furthermore, specimens in juvenal plumage were available from only three of the five groups delimited here, with no specimens from Southeastern Brazil Highlands and Llanos de Moxos.

First basic plumage: Birds in this plumage are identifiable by their lighter and brownish crown, their yellowish supercilium, and more heavily streaked upperparts. Feathers of the crown and nape light olive brown (2.5Y 5/4) with the central shafts black (2.5Y 2.5/1), resulting in a streaked appearance; interscapulars brownish yellow (10YR 6/8) with the central shafts black (2.5Y 2.5/1); rump brownish yellow (10YR 6/8); upper tail coverts yellowish brown (10YR 5/6) with the central shafts black; chin and throat yellow (10YR 8/6); breast yellow (10YR 7/6), with the feathers presenting a small spot very dark grayish brown (10YR 3/2) in the central shaft, resulting in a spotted appearance; belly and sides yellow (10YR 7/6), with the central shafts of side feathers very dark grayish brown (10YR 3/2), resulting in a streaked appearance; supercilium and lores yellow (2.5Y 8/6); auriculars light yellowish brown (2.5Y 6/4); primaries and secondaries very dark brown (10YR 2/2) edged pale yellow (10YR 6/4) on the outer vane; greater wing coverts and tertials very dark brown (10YR 2/2) edged yellowish brown (10YR 5/ 8) on the outer vanes; marginal wing coverts gray (5Y 5/1); rectrices very dark brown (10YR 2/2) edged light yellowish brown (2.5Y 6/4) on the outer vanes; under wing coverts whitish. Individual and wear variation: difficult to appreciate given the small number of specimens available. Geographic variation: marked, even though the scarce material available precludes a thorough evaluation of it. Birds from the northern range (Southeastern Brazil Highlands) are much paler throughout and with a greenish cast on the upperparts. Main differences are: feathers of crown and nape olive (5Y 5/3) with the central shafts black, resulting in a streaked appearance; interscapulars light olive brown (2.5Y 5/3) with the central shafts black; rump light olive brown (2.5Y 5/4); upper tail coverts olive brown (2.5Y 4/3); chin pale yellow (2.5Y 8/3); throat pale yellow (2.5Y 8/4); breast pale yellow (2.5Y 7/4) with discrete and indistinct spots grayish brown (2.5Y 5/2); belly pale yellow (2.5Y 7/4). The first basic plumage of the isolated population in Llanos de Moxos is similar to that of southern specimens (Río de la Plata and Southern Brazil), but with a somewhat yellower cast in the underparts.

Definitive basic plumage: Feathers of the crown and nape olive brown (2.5Y 4/3) with the central shafts dark gray (2.5Y 3/1), resulting in a streaked appearance; interscapulars olive brown (2.5Y 4/4) with the central shafts black (2.5Y 2.5/1); rump olive brown (2.5Y 4/3); upper tail coverts olive brown (2.5Y 4/3) with the central shafts black (2.5Y 2.5/1); chin and throat yellow (10YR 8/6); breast and belly yellow (10YR 7/8), sides brownish yellow (10YR 6/6); crissum brownish yellow (10YR 6/6), supercilium and lores pale yellow (2.5Y 8/3); auriculars dark grayish brown (2.5Y 4/2); primaries and secondaries very dark brown (10YR 2/2) edged pale brown (2.5Y 6/4) in the outer vanes; greater wing coverts and tertials very dark brown (10YR 2/2) edged yellowish brown (10YR 5/8) in the outer vanes; marginal wing coverts gray (5Y 5/1); rectrices very dark brown (10YR 2/2) edged light yellowish brown (2.5Y 6/4) in the outer vanes; under wing coverts whitish. Individual variation: marked, especially on the intensity of pigmentation. Some specimens from the extreme southern range are comparatively paler than usual for Río de la Plata, as illustrated by an extreme example from Uruguay ( USNM 630463), which is as pale as some specimens from the extreme northern range (Southeastern Brazil Highlands). Wear variation: the overall appearance of the specimen varies considerably with plumage condition, because worn plumage is paler than new plumage. This is due to both plumage fading, which changes the hue of feathers, and abrasion, which progressively shortens the more richly colored distal portion of the feathers’ barbs. Therefore, specimens with very worn plumage become paler throughout, with their underparts becoming light buff, because ventral feathers have a whitish band proximal in relation to the buff tips. The upperparts become progressively less streaked, which is due to the reduction in contrast between the dark central shaft and the paler borders of the dorsal feathers. As a consequence, specimens with worn plumage from Río de la Plata and Southern Brazil look like freshly plumaged specimens from Southeastern Brazil Uplands. Specimens with worn plumage from Southeastern Brazil Highlands show pale yellow (2.5Y 8/2), almost whitish, underparts. Geographic variation: the large geographic variation in color observed in this species has a strong clinal component ( Figure 4 View FIGURE 4 ), but with a remarkable exception for birds from Llanos de Moxos (see below). Generally, birds from the southern portion of the range (Río de la Plata and Southern Brazil) are more richly colored, as described above, and birds from the higher areas in the northern portion of the range (Southeastern Brazil Highlands) are grayer and paler throughout and less streaked on the upperparts (main differences: birds from Southeastern Brazil Highlands show crown and nape dark gray (10YR 4/ 1) and unstreaked; interscapulars dark gray (10YR 4/1), with the central shafts black (2.5Y 2.5/1); chin white (2.5Y 8/1); throat yellow (2.5Y 8/8); breast pale yellow (2.5Y 7/4); belly pale yellow (2.5Y 7/3); sides light olive brown (2.5Y 5/3); primaries and secondaries black (10YR 2/1) edged dark gray (10YR 4/1). Birds from the Southeastern Brazil Uplands generally show intermediate coloration (main differences: feathers of the underparts light gray 2.5Y 7/2 or pale yellow 2.5Y 7/3; feathers of upperparts edged olive gray 5Y 4/2 or dark grayish brown 2.5Y 4/2). Birds from Llanos de Moxos are similar to birds from the Southeastern Brazil Uplands, only slightly more richly colored, especially in the underparts, but with extremes of variation (e.g. LSUMZ 124923) much like specimens from Río de la Plata and Southern Brazil ( Figure 5 View FIGURE 5 ).

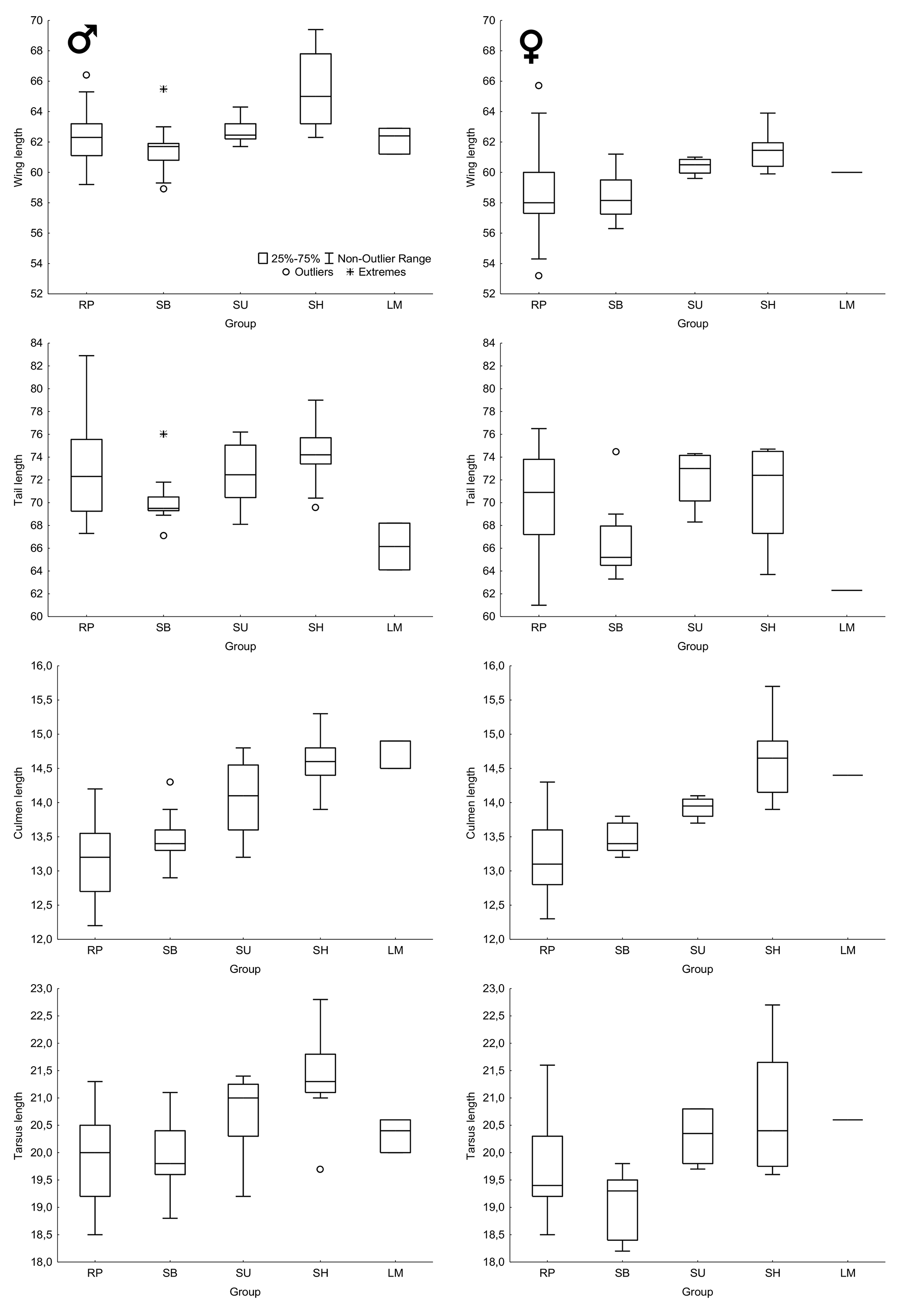

Body size. Males and females of the Río de la Plata present similar body measurements ( Table 1 View TABLE 1 ) for culmen, tarsus, and tail length, but wing length is significantly longer in males than in females (P <0.001). Mean wing length of males also seems to be longer than those of females for all other groups ( Figure 6 View FIGURE 6 ), but, given the small sample size, no statistical test was performed. Despite some differences in mean body size between the groups investigated here, considerable overlap in measurements exist between them ( Table 1 View TABLE 1 , Figure 6 View FIGURE 6 ) and no morphometric characters are diagnostic at a 95% level using the method of Patten & Unitt (2002).

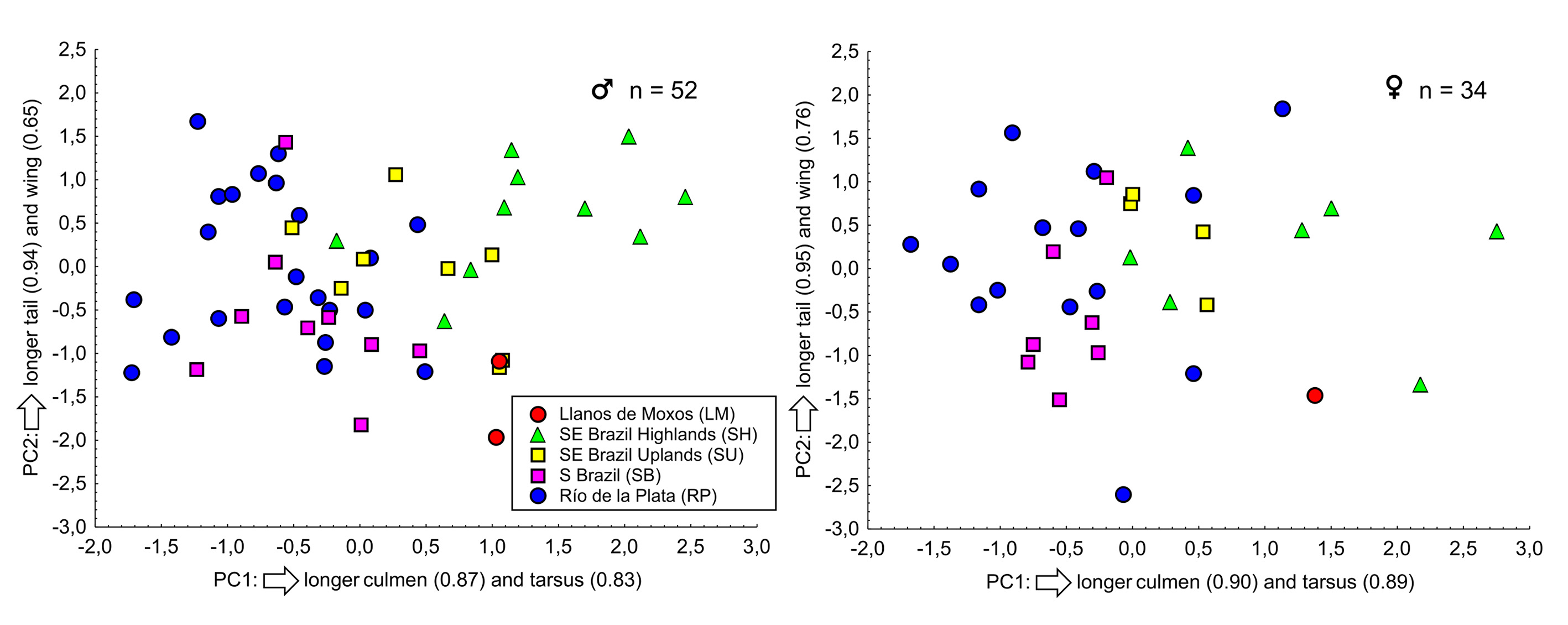

The PCA ( Figure 7 View FIGURE 7 ) demonstrated no clear-cut separation between the populations defined here. The contribution ratios of the first principal component (PC1, with an eigenvalue of 1.99 for males and 2.46 for females) were 49.78% for males and 61.60% for females. The second principal component (PC2, with an eigenvalue of 1.15 for males and 0.91 for females) contributed with 28.80% and 22.80%, respectively. PC1 represents a relationship between culmen and tarsus length, and PC2 represents a relationship between tail and, to a lesser extent, wing length.

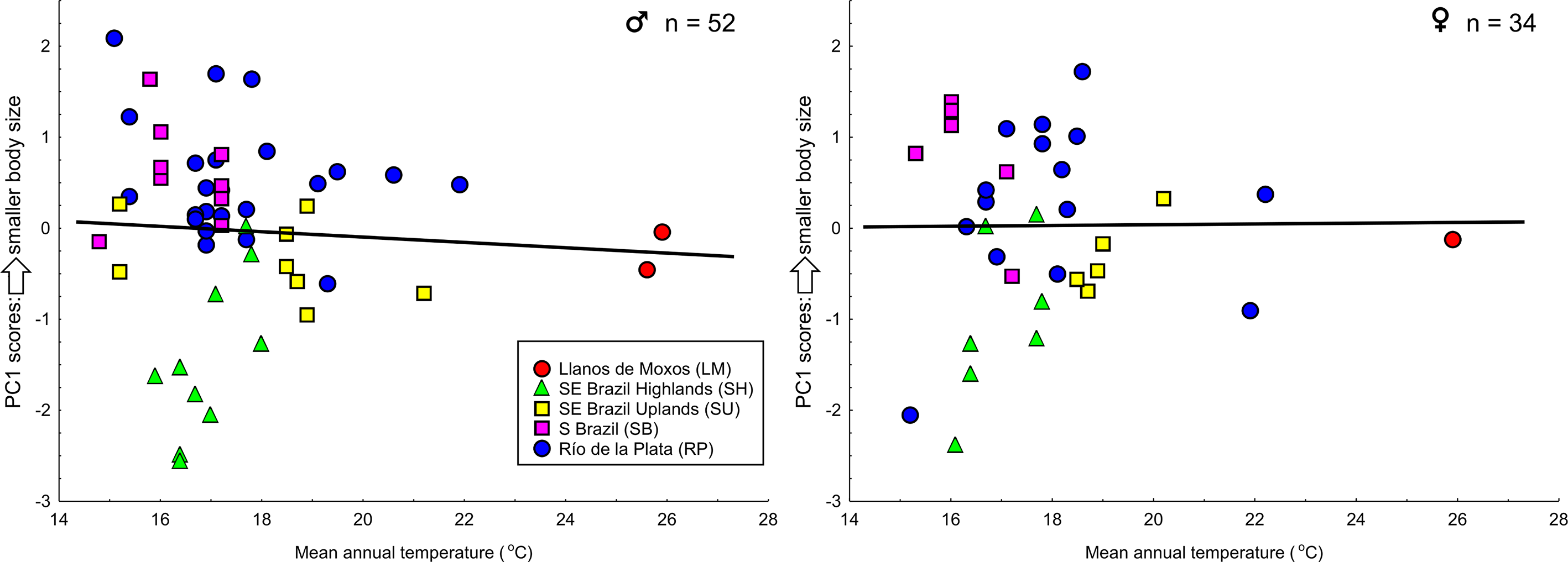

The Spearman's correlation coefficient revealed no correlation between body size and mean annual temperature for either males (R = -0.098, P = 0.49) or females (R = -0.041, P = 0.82) ( Figure 8 View FIGURE 8 ). Birds from Southeastern Brazil Highlands averaged larger than birds from the other groups (some overlap in body size does exist), but a linear north-south cline does not describe the variation in body size observed in the species.

Discussion

Habitat. The mountainous and comparatively dry habitat where I recorded the Long-tailed Reed Finch in the Southeastern Brazil Highlands strongly contrasts with that previously reported for the species, which is said to inhabit low elevation seasonally wet grasslands, southern temperate grasslands, and freshwater marshes ( Parker et al. 1996). The species seems to use distinct habitat types in different parts of its range, with southern populations associated with wetter habitats ( Wetmore 1926; Belton 1994; Narosky & Yzurieta 2003), and northern populations associated with drier, mountainous habitats. An exception to this rule is the disjunct population from Llanos de Moxos, which is also associated with lowland seasonally wet grasslands ( Maillard et al. 2008; Lane 2014). I stress that members of all genera closely related to Donacospiza , such as Cypsnagra , Poospizopsis , Urothraupis Taczanowski & von Berlepsch , and Microspingus , are, with few exceptions, associated with open or semiopen habitats far from water, such as open savannas, shrublands, low woodlands, and forest borders, frequently in mountainous areas ( Fjeldså & Krabbe 1990; Ridgely & Tudor 2009).

Breeding season. Comprehensive data on the breeding biology of the species is lacking, but the incubation period is 13 days and the nestling period is 12 days ( Di Giacomo 2005). The breeding season estimated from gonadal data on the labels of museum specimens (Sep–Jan) agrees with the scattered information available in the literature. Data from the southern range of the Long-tailed Reed Finch suggest nesting from Sep–Mar, with birds in breeding condition collected from Sep–Jan ( Gibson 1885; Hartert & Venturi 1909; Wetmore 1926; Pereyra 1938; Darrieu et al. 1988; Belton 1994; Darrieu & Camperi 1996; Di Giacomo 2005; de la Peña 2013; Pretelli et al. 2013; data presented here). An adult was observed feeding a juvenile Molothrus bonariensis on 2 Feb 1986 ( Di Giacomo & Aguilar 1987). Therefore, breeding of the southern populations extends from Sep–Mar, and even later in Argentina, as indicated by specimens with enlarged testes from 5 Jun ( Darrieu & Camperi 1996) and a juvenile (NHMUK 1897.11.14.35) collected on 29 Jun. The scarce breeding data from the isolated population in Llanos de Moxos suggests a similar breeding season, with two family groups feeding fledglings on 7 Sep 2013 ( Lane 2014) and males with enlarged testes in Oct ( Schimitt & Schimitt 1987). A “juvenil” bird was observed in Bolivia in Jul ( Maillard et al. 2008).

Plumage sequence and molts. Retention of the juvenal plumage for about 1–2 months after leaving the nest is a common pattern in temperate Thraupidae and, even though molt is poorly known in Neotropical passerines ( Ryder & Durães 2005), this same pattern seems to apply to the Long-tailed Reed Finch. Ryder & Durães (2005) emphasized that a very distinct juvenal plumage, like that reported here, has been described for a few genera of tanagers, but this conclusion applies only to the traditional systematic arrangement of the family. With the recent and widespread use of molecular data, the systematic arrangement of Thraupidae has changed dramatically, with the inclusion in the family of many genera traditionally considered finch-billed New World sparrows ( Barker et al. 2013b; Burns et al. 2014, 2016). This systematic rearrangement revealed that many genera of the currently recognized Thraupidae have a very distinct juvenal plumage, as demonstrated by members of several genera of Poospizini ( Fjeldså & Krabbe 1990; Rising 2011).

Morphological variation. Data summarized here demonstrate that the alleged sexual dichromatism previously reported in the species is a misinterpretation of morphological variation due to age, plumage condition, and geography. Geographic variation in the species is somewhat clinal, with smaller, more richly colored birds found in wet lowlands at southern localities and larger, paler birds found in dry highlands at northern localities. Nevertheless, there are several exceptions to this rule, best exemplified by the northernmost population isolated in the seasonally wet grasslands of Llanos de Moxos, which is more richly colored than expected by range. This pattern is also complicated by a large amount of individual variation, best exemplified by the abnormally pale specimens from Uruguay discussed above. Gloger’s rule, the tendency for populations in wetter areas to be more heavily pigmented than populations in drier areas ( Gloger 1833; Zink & Remsen 1986), might be a possible explanation for the geographical pattern of color variation in the species, with darker and more richly colored populations found in wet areas, and lighter and paler populations found in drier areas. Even though this ecogeographical rule has been reported for other Neotropical bird species ( Hayes 2001; Bolívar-Leguizamón & Silveira 2015), this hypothesis requires further investigation.

Conclusion. I conclude that, with no solid basis for splitting the species into two or more taxa, the Long-tailed Reed Finch should be considered a single, highly polymorphic species, widely distributed across an extensive area in south-central South America, where it inhabits a wide range of habitat types. The marked geographic variation of the Long-tailed Reed Finch remained overlooked until now, apparently due to: 1) the small number of specimens available in museums; 2) the narrow geographic coverage of specimens in all major ornithological collections; and 3) the lack of modern revisions of the taxonomy and morphology of the species, although the nature of morphological variation in the Long-tailed Reed Finch was disputed for decades. This study is another example of how poorly understood the alpha taxonomy and the morphological and geographic variation of Neotropical birds remains (e.g. Lopes & Gonzaga 2014, 2016a, b; Lopes 2017). This poor level of knowledge represents a key impediment to a thorough accounting of Neotropical bird diversity.

TABLE 1. Morphometric analysis of body measurements of the Long-tailed Reed Finch Donacospiza albifrons. All measurements are given in mm, except body mass, which is given in g. Given the small sample size for several populations, no statistical comparison between them was performed.

| Wing | ♂ ♀ | Mean 62.2 60.0 | SD 0.87 - | Min–Max 61.2–62.9 - | n 3 1 | Mean 62.3 58.7 | SD 1.83 2.92 | Min–Max 59.2–66.4 53.2–65.7 | N 25 18 | Mean 61.6 58.4 | SD 1.96 1.70 | Min–Max 58.9–65.5 56.3–61.2 | n 9 8 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tail Tarsus | ♂ ♀ ♂ | 66.2 62.3 20.3 | 2.90 - 0.31 | 64.1–68.2 62.3 20.0–20.6 | 3 1 3 | 72.6 70.5 19.9 | 4.06 4.39 0.80 | 67.3–82.9 61.0–76.5 18.5–21.3 | 24 16 25 | 70.3 66.6 19.9 | 2.48 3.62 0.74 | 67.1–76.0 63.3–74.5 18.8–21.1 | 9 8 9 |

| Culmen | ♀ ♂ ♀ | 20.6 14.8 14.4 | - 0.23 - | 20.6 14.5–14.9 - | 1 3 1 | 19.8 13.1 13.1 | 0.92 0.50 0.92 | 18.5–21.6 12.2–14.2 18.5–21.6 | 17 24 18 | 19.1 13.5 13.5 | 0.62 0.43 0.21 | 18.2–19.8 13.0–14.3 13.2–13.8 | 8 9 7 |

| Body mass | ♂ | 18.9 | 0.76 | 18.1–19.6 | 3 | 14.7 | 1.48 | 13.7–16.4 | 3 | - | - | - | - |

| ♀ | 16.1 | - | - | 1 | 14.2 | 0.24 | 14.0–14.5 | 4 | 15.0 | - | - | 1 |

Variable Sex Llanos de Moxos (LM) Río de la Plata (RP) Southern Brazil (SB)

continued.

| ANSP |

Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia |

| AMNH |

American Museum of Natural History |

| FMNH |

Field Museum of Natural History |

| LSUMZ |

Louisiana State University, Musuem of Zoology |

| MCNA |

Museo de Ciencias naturals de Alava |

| MNHN |

Museum National d'Histoire Naturelle |

| MNRJ |

Museu Nacional/Universidade Federal de Rio de Janeiro |

| MPEG |

Museu Paraense Emilio Goeldi |

| MZUSP |

Museu de Zoologia da Universidade de Sao Paulo |

| NHMUK |

Natural History Museum, London |

| NMW |

Naturhistorisches Museum, Wien |

| NRM |

Swedish Museum of Natural History - Zoological Collections |

| SMF |

Forschungsinstitut und Natur-Museum Senckenberg |

| USNM |

Smithsonian Institution, National Museum of Natural History |

| ZMB |

Museum f�r Naturkunde Berlin (Zoological Collections) |

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.