Neanaperiallus defunctus Fusu, 2023

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/ 10.11646/zootaxa.5318.2.2 |

|

publication LSID |

lsid:zoobank.org:pub:CF8E0B91-9AF7-4075-963D-9BC977B41852 |

|

DOI |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.8168995 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/03C7737C-A608-FFA1-FF39-FE67FAB1FADC |

|

treatment provided by |

Plazi |

|

scientific name |

Neanaperiallus defunctus Fusu |

| status |

sp. nov. |

Neanaperiallus defunctus Fusu sp. nov.

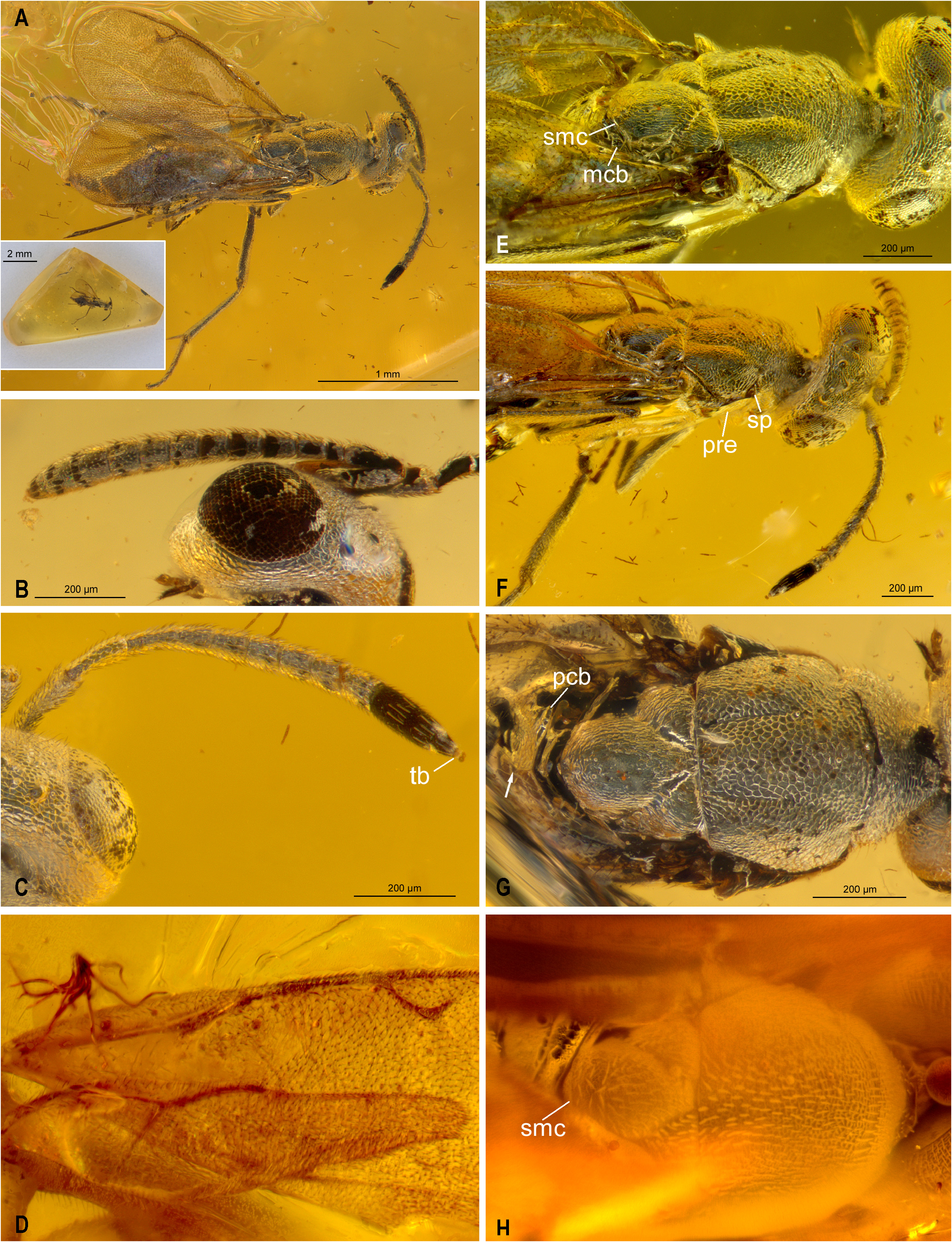

Figs 4A‒C, E‒G View FIGURE 4 , 5 View FIGURE 5

http://zoobank.org/ urn:lsid:zoobank.org:act:526EC759-C9AC-4C08-AE83-F8FCBFCDEAC0

Type material. Holotype ♀ (deposited in AICF). Baltic amber of Polish origin, no. LF2101. The fossil is preserved in a 2 mm thick, triangular amber piece with sides of about 10 × 7 × 6 mm ( Fig. 4A View FIGURE 4 , inset). Fossil with dorsal side very near the surface and part of the wing venation of the right fore wing, including marginal vein and basal parts of stigmal and postmarginal veins, chipped off ( Fig. 4A View FIGURE 4 ).

Etymology. From the Latin defunctus (deceased), in reference to the taxon being extinct.

Diagnosis. The new species differs from L. janzeni by its gracile antenna and legs and in sculpture of the mesoscutum having a larger mesh size. See also Remarks.

Description. Length 2.5 mm including ovipositor sheaths. Body ( Fig. 4A View FIGURE 4 ) silvery due to thin layer of air surrounding it, but probably uniformly brown based on parts of antennae, prepectus, legs and some gastral tergites and sternites (these regions brown because during preparation part of the air layer was displaced by water that entered the inclusion through the chipped-off parts of the fore wing).

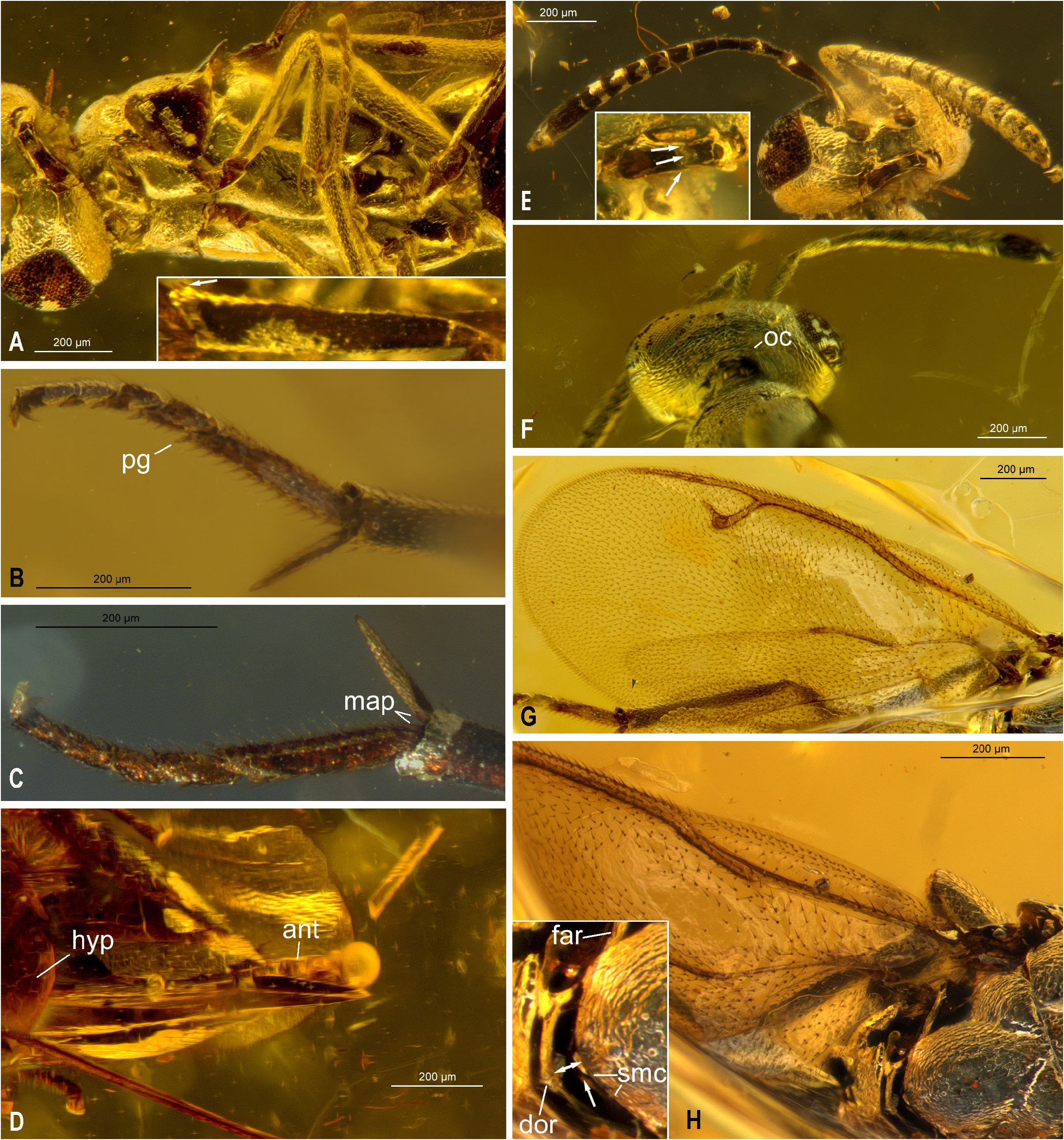

Head width: length: height = 44: 21: ~33. Head in dorsal view ( Fig. 4F View FIGURE 4 ) lenticular; vertex rounded into occiput; interocular distance ~0.4× head width (19: 44); ocelli arranged in an obtuse triangle, with MPOD: OOL: POL: LOL = 79: 90: 253: 147. Eyes in anterior view with inner margins not divergent ventrally ( Fig. 5E View FIGURE 5 ) or at least not conspicuously divergent (examination in direct frontal view not possible); scrobal depression shallow, with non-carinate lateral margin; torulus with lower margin in line with or slightly ventral to lower ocular line; malar sulcus straight; labrum exposed and at right angle to clypeus. Mandible apparently with three teeth ( Fig. 5E View FIGURE 5 , inset: arrows) (contact area between mandibles covered with a white substance). Eye apparently bare. Antenna ( Figs 4A‒C View FIGURE 4 ) with scape spindle-shaped (the limit between scape and radicle not observable and scape width not measurable in exact lateral view but scape at least about 5× as long as wide); ratios of pedicel, funiculars and clava ( Fig. 4B View FIGURE 4 ) measured in lateral view (length: width) = (25: 9), (7: 7), (12: 8.5), (13: 10), (12.5: 11), (12: 12), (12: 13), (12.5: 13.5), (14: 14), (35.5: 15); fl 1 differentiated from remaining preclaval flagellomeres by being slightly narrower and quadrate, and without mps; fl 2 longer than wide but slightly shorter and evidently narrower than fl 3, which is the longest flagellomere other than fl 8, flagellomeres following fl 1 subequal in length but gradually widening toward clava, resulting in fl 2 ‒fl 4 being longer than wide and fl 5 ‒fl 8 slightly transverse or quadrate; clava with strongly abutting clavomeres and micropilose sensory region small, restricted to apex of terminal segment so as to appear as a rounded terminal button ( Fig. 4C View FIGURE 4 : tb). Antenna in dorsal view ( Fig. 4C View FIGURE 4 ) with fl 2 and fl 3 even more obviously narrower compared to apical preclaval flagellomeres. Pronotum in dorsal view ( Fig. 4G View FIGURE 4 ) about one-third length of mesoscutum (26: 73) and about 2.8× as wide as long medially, with dorsal surface sloping from posterior margin; in lateral view not readily visible, but apparently almost vertical and barely convex ( Fig. 4F View FIGURE 4 ); pronotum uniformly reticulate, and with dark setae. Mesoscutum only slightly shoulder-like posterior to pronotum, about 1.25× as wide as long; reticulate with large cells, the sculpture smaller on lateral lobes compared to median lobe ( Fig. 4G View FIGURE 4 ); mesoscutal furrows not differentiated in sculpture, but well visible along entire length because lateral and median lobe meet at an angle, the furrow deepest anterolaterally medial to spiracle ( Fig. 4G View FIGURE 4 ). Mesoscutellar-axillar complex with inner angles of axillae separated by 0.3× maximum width of axilla and 0.4× anterior width of axilla; scutoscutellar sutures crenulate ( Fig. 4E View FIGURE 4 ); mesoscutellum and axillae low convex and in about the same plane, with reticulate sculpture changing to imbricate with transverse cells on lateral surfaces; with inconspicuous decumbent setae ( Figs 4E, F View FIGURE 4 ); mesoscutellum not carinate laterally, with distinct frenal arm ( Fig. 5H View FIGURE 5 : far), without an obvious frenum but with sculpture along apical margin aligned, the sculptural difference differentiating a thin carina ( Figs 4E View FIGURE 4 , 5H View FIGURE 5 inset: smc) that delineates a lunate, down-sloped mesoscutellar apex ( Fig. 5H View FIGURE 5 : arrow). Metanotum with dorsellum an oblique semicircular band, cup-like over apex of mesoscutellum ( Fig. 5H View FIGURE 5 insert: dor), with an evident gap ( Fig. 5H View FIGURE 5 : double arrow) between the two sclerites; lateral panel anteriorly crenulate ( Fig. 4E View FIGURE 4 : mcb) (but crenulation not clearly visible because of position of right wing and a small brown inclusion in the amber on left side); in lateral view apex of mesoscutellum, dorsellum and propodeum forming a continuous sloping surface ( Figs 4E, F View FIGURE 4 ). [The separation between mesoscutellum and dorsellum was less visible before part of the air layer around the fossil was displaced by some water during preparation (cf. Fig. 4E View FIGURE 4 with 5H).] Propodeum not differentiated into plical and callar regions, its median length about half lateral length, anteriorly with a crenulate band medial to spiracle ( Fig. 4G View FIGURE 4 : pcb), and with a median carina, the carina widening posteriorly from about mid length into a triangular area ( Fig. 4G View FIGURE 4 : arrow) (distal end of the carina mostly obscured by the wing); mostly bare except with long setae lateral to spiracle ( Fig. 4E View FIGURE 4 ); spiracle close to anterior margin of propodeum; propodeal foramen in dorsal view semicircular ( Fig. 4G View FIGURE 4 ). Mesosoma with acropleuron uniformly convex and smooth, finely alutaceous only anteriorly and posteriorly, with no visible setae, extending posteriorly to posterodorsal angle of mesocoxa and likely to metapleuron; upper mesepimeron not visible, lower mesepimeron a flat and narrowly elongated triangular region between acropleuron and base of mesocoxa ( Fig. 5A View FIGURE 5 ); acropleural sulcus crenulate, almost linearly directed from above mesocoxa, only in anterior third gradually curved towards posterodorsal angle of prepectus; mesepisternum large, in lateroventral view about same size as acropleuron ( Fig. 5A View FIGURE 5 ), with no visible setae. Metapleuron not visible. Dorsal protibial spicules absent, with two dorsoapical spicules ( Fig. 5A View FIGURE 5 , inset: arrow); middle and hind legs not conspicuously long, of about same length, and hind leg not unusually modified, with two tibial spurs; mesocoxa with basolateral cavity present ( Fig. 5A View FIGURE 5 ); mesotibia with a row of 4 spine-like pegs apically ( Fig. 5C View FIGURE 5 : map), and with mesotibial spur 1.7‒1.9× as long as apical width of mesotibia depending on viewing angle; mesotarsus slender, with basitarsus in lateral view about 5.4× as long as wide and of similar length as combined length of four apical tarsomeres, the mesotarsal peg pattern similar along anterior and posterior margins, consisting of robust spines basally that gradually become thicker and more peg-like towards apex of respective tarsomere, with only the apical-most seta on both sides of tarsomeres 1‒4 distinctly peg-like ( Fig. 5B View FIGURE 5 : pg). Fore wing ( Fig. 5G View FIGURE 5 ) appearing uniformly infuscate, slightly brownish; costal cell with ventral surface uniformly setose, but dorsally with two rows of setae along leading margin for length of parastigma plus about distal half of costal cell; basal cell and disc uniformly setose except for bare vanal and cubital areas ( Fig. 4E View FIGURE 4 ) and an elongate, broad, bare band posterior to parastigma and basal third of marginal vein; the bare band separated from basal fold and parastigma by about three lines of setae and though it is asetose dorsally, with about four inconspicuous setae ventrally ( Fig. 5H View FIGURE 5 ); cc: mv: pmv: stv = 685: 481: 472: 192. Gaster lanceolate ( Fig. 4A View FIGURE 4 ) (slightly distorted because of internal gas build-up during taphonomic processes); with seven tergites, each with a straight posterior margin (whether terminal tergite is completely fused into a syntergum or Gt 7 and Gt 8 are separated dorsally by a suture is hidden by Gt 6 which extends to level of cerci but possibly present is a line or suture ventral to cercus in lateral view); syntergum with cercus closer to anterior than to posterior margin, short behind cerci, and apically truncate, hence ovipositor sheaths mostly not covered ( Fig. 5D View FIGURE 5 ); with a bare, cylindrical and slightly wrinkled anal tube posterior to syntergum over most of rest of ovipositor sheaths ( Fig. 5D View FIGURE 5 ); hypopygium extending half-length of gaster ( Fig. 5D View FIGURE 5 ). Ovipositor sheaths projecting beyond syntergum but only slightly beyond anal tube.

Remarks. The holotypes of N. masneri and N. defunctus appear very different upon superficial comparison, but this is partly because of their different preservation states and likely because all features cannot be viewed from exactly the same angles in the two inclusions. The holotype of N. masneri superficially appears to have lanceolate mesonotal setae, the mesoscutum appears uniformly convex, the costal cell appears mostly bare, and the scutoscutellar sutures appear linear. However, all of these apparent features likely reflect the inclusion being covered by a thin layer of a white substance, and can be reinterpreted in the light of the newly discovered specimen of N. defunctus . As already mentioned by Gibson (2009) and above, the conspicuous lanceolate setae are certainly an artefact since they appear normal in lateral view, and the mesoscutum can be reinterpreted as having weak notaular furrows that differentiate the mesoscutum into median and lateral lobes that are noticeable as different shadings in Fig. 4H View FIGURE 4 , but also in Gibson (2009, fig. 59). Further, even though the published photograph of the costal cell ( Gibson 2009, fig. 62) appears bare except for a line of setae along anterior margin, an unpublished alternate image of the other wing ( Fig. 4D View FIGURE 4 ) shows the costal cell to be uniformly setose. The scutoscutellar sutures likely are also crenulate, though some of the perceived transverse ridges in fig. 4H are setae and some are cell walls, because in N. defunctus the crenulate nature of the suture is also more or less visible depending on the angle and lighting conditions.

Aside from these apparent differences and some others, such as relative placement of the toruli that might reflect angle of view, the two specimens are quite similar. Both individuals have similar shaped heads with an occipital carina (a feature otherwise not shared by any species formerly included in Eupelmidae or Tanaostigmatidae ), a mesosoma and propodeum that are very similar in shape, similar comparative size of all sclerites, including the presence of a strong frenal arm, crenulate lines of sculpture laterally on the metanotum and along the anterior margin of the propodeum, and similar position of the spiracle. The fore wing setation and the ratios between the veins of the two species is also similar.

Neanaperiallus defunctus differs from N. masneri in having more gracile antenna and legs and in mesoscutal sculpture. In N. defunctus , the flagellum is narrower basally, with fl 2 evidently narrower than fl 3 and especially in dorsal view fl 2 and fl 3 are obviously narrower than the apical flagellomeres, and fl 2 is also slightly shorter than fl 3, whereas the flagellum is more cylindrical in N. masneri and fl 2 is the longest flagellomere. Further, the mesotibial spur is 1.7‒1.9× as long as the apical width of the mesotibia and the mesotarsus is slender, with the basitarsus in lateral view about 5.4× as long as wide, whereas in N. masneri the mesotibial spur is only about 1.5× as long as the apical width of the mesotibia and the basitarsus is only about 3× as long as wide. Although these differences might in part reflect measurements from slightly different angles of view, there is also a conspicuous difference in sculpture of the mesoscutum between the two species. The reticulate mesh size is noticeably larger for N. defunctus ( Fig. 4G View FIGURE 4 ) compared to much smaller, more reticulate-punctate mesh size for N. masneri ( Fig. 4H View FIGURE 4 ; Gibson 2009, fig. 59). The acropleural sulcus also appears different in the two species, being curved in its anterior third in N. defunctus ( Fig. 5A View FIGURE 5 ) but almost straight-oblique in N. masneri ( Fig. 1A View FIGURE 1 ).

The last obvious difference between the two inclusions is the setal arrangement of the apical third of the mesoscutellum (cf. Figs 4 E, H View FIGURE 4 ). In N. masneri the setae are arranged in a sparse whorl, with the setae directed more or less laterally rather than posteriorly ( Fig. 4H View FIGURE 4 ) similar to some species of Merostenus Walker ( Fusu 2013, fig. 15), whereas all the setae are apparently directed posteriorly in N. defunctus ( Fig. 4E View FIGURE 4 ). However, because the setae in N. masneri are much more conspicuous, it is possible that the setal pattern of the two species is more similar than is apparent, the setae being more difficult to see and interpret in N. defunctus .

An important aspect of Neanaperiallus not discussed in detail before (because it is not readily visible in N. masneri ) is the structure of the apex of the mesoscutellum and the metanotum. In N. defunctus the dorsellum is raised and cup-like over the mesoscutellar apex, oblique relative to a down-sloped surface visible just behind the apical marginal carina. This apical portion of the mesoscutellum ( Fig. 5H View FIGURE 5 , inset: arrow) is likely homologous with the frenum, being located immediately posterior to the frenal arms ( Fig. 5H View FIGURE 5 , inset: far) and visible because of a slight separation between the dorsellum and mesoscutellum ( Fig. 5H View FIGURE 5 insert: double arrow). Because this gap is visible in both Neanaperiallus fossils, it likely is not an artefact of preservation. Besides this separation between the mesoscutellar apex and dorsellum ( Gibson 2009, fig. 59) the fossil of N. masneri possibly also shows the presence of a marginal carina ( Fig. 4H View FIGURE 4 : smc), as in N. defunctus . Thus, the metanotum in Neanaperiallus is similar to Calosotinae and many female Eupelminae , and is likely correlated with the apex of the mesoscutellum being differentiated in a narrow vertical frenum. Members of these two subfamilies also often have a visible gap as described above, which may be structurally necessary for mesonotal flexing. A marginal rim is also present in Metapelma , but in this genus the mesoscutellum overlies the dorsellum, thus lacking a vertical apical surface behind the rim, though the mesoscutellum and dorsellum are also separated by a narrow gap ( Gibson 2009, fig. 14).

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.